Last Voyage of the Hornet: the Story That Made Mark Twain Famous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anticipating Anchoring Story and Photos by Jeff Merrill

power voyaging Anticipating anchoring STORy ANd phOTOS by JEff MERRIll he freedom to explore which goes into great detail Let’s presume that the Tremote cruising grounds on a number of theoretical windlass (horizontal or verti- and to anchor out overnight aspects and practical applica- cal) and anchor (so many or for days at a time is one tions for a variety of situa- variations) have already been of the great attractions of tions. Over time voyagers selected and installed on the trawler lifestyle. Under- generally develop techniques your trawler and are appro- standing how your ground for setting their anchor, priately sized to provide breaking it loose and you with sufficient holding securely stowing the strength. With this article ground tackle while I’d like to share some com- underway — practice, mon sense techniques you fine-tune and keep can adapt to your trawler learning. that will improve your com- There are many fort level and to help you factors involved in “dial-in” your anchoring selecting a safe place routine. Be sure that the to drop the hook — connection between your wind, tide, currents, anchor and chain (swivel other boats, etc. You with Loctite or shackles with seizing wire on the pins) is secure so it can’t disconnect. Above, an tackle connects your Securing the anchor anchor bridle floating palace to the It is vitally important that setup evenly sea floor and being your anchor, when raised distributes the properly prepared will and stowed on its roller, load. Right, an give you more con- is secure in place and not anchor keeper fidence to visit new free to wobble around. -

Investigation of Abandoned WW II Wrecks in Palau

Investigation of Abandoned WW II Wrecks in Palau Tomo Ishimura1 Abstract Over forty Japanese vessels were sunken in the water of Palau during WWII. Some wrecks sunk in the shallow water at a depth of 20 meters or less and were salvaged. Other wrecks at 30 meters depth or more still remain and are legally protected by the authority of Palau Government but are seriously threatened by illegal treasure hunters. Initial efforts to identify human remains of Japanese soldiers were made in 2005. As part of an archaeology advisory team for the Japanese Government I carried out underwater surveys of sunken WWII vessels in Palau. In 2010 and 2011, I conducted investigations of the WWII vessels again, together with on-shore research on sites and features associated with the Japanese occupation period, funded by the Takanashi Foundation for Arts and Archaeology (Japan). The research revealed that the most of the vessels sunken in Palau were not genuine military vessels of Japanese Imperial Navy or Army but converted vessels originally built for non-combat purposes. These vessels were slow in speed and not well-equipped for combat activity. Most of them were destroyed by American aerial bombing on March 30th 1944. The evening before (March 29th) the main force of the Japanese Combined Fleet, including its flagship Musashi, retreated from Palau. It is clear that the vessels left in Palau were abandoned as a “third wheel” of the Combined Fleet. These abandoned-converted vessels include cargo carriers, tankers, whaling boats and fishing boats. This implies that Japanese troops were experiencing a difficult and desperate campaign at that time. -

Trabalhos De Arqueologia 18

Sources for Lusitanian shipbuilding ❚ RICHARD BARKER ❚ Introduction “...Still there is more. In the ancient archives of the kingdom, at whose head I found myself, there exists a most ancient manuscript that is a contract between the king D. Afonso III and the Master of the Knights of Santiago, Paio Peres. In that document it is determined that the tribute of mermaids and other animals fished on the beaches of the same Order ought to be paid not to the Master but to the Kings. From which it is easy to collect that mermaids were frequent in our waters, seeing that a law had been promulgated about them. Enough: it is not worth continuing to speak of tritons, sea-nymphs and mermaids, and we renew the thread of the discourse”. Damião de Gois, Lisboa de Quinhentos, 1554 (Gois, 1554-1937, p. 30)1, offers this sad tale of over-fishing in the third quarter of the thirteenth century. The same might have been said of the wrecks of Portuguese ships, whose absence had been the source of some woe to schol- ars such as João da Gama Pimentel Barata and Octávio Lixa Filgueiras. After all, it was Por- tuguese ships that really opened up the world in the fifteenth century, and even much of the so-called Spanish Armada had actually been seized from the Portuguese arsenals. Happily, the sirens have finally led our Portuguese colleagues to the true fishing grounds. Perhaps the mer- maids will follow. Portugal has a maritime history out of all proportion to its size, but after a brief survey, towards the overall theme of the conference, this paper will concentrate on three aspects of nau- tical archaeology that have been illuminated by the contents of Portuguese libraries. -

Grand Banks Operations Manual

GRAND BANKS OPERATIONS MANUAL Welcome aboard! We are happy you have chosen “Latis” for your vacation. We are sure you will enjoy cruising the wonderful islands of the Pacific Northwest. We trust this manual will help you become familiar with the boat. If you have questions about the boat or about places to visit, please do not hesitate to ask any of the AYC staff. The Grand Banks 46 ranks among the finest cruising yachts ever produced. With her timeless trawler profile, sea-kindly semi-displacement hull and elegant teak interior the 46 Classic has defined cruising luxury since her introduction in 1985. In the long elegant tradition of Grand Banks, Latis epitomizes the classic cruising vessel of the Inside passage. She is comfortable, well laid out, and a great motor yacht for exploring in grace and comfort. Latis is 46 foot Sedan Cruiser in a traditional design with a comfortable salon, staterooms, and deck space with easy walk around space on each side of the vessel. We wish to fair winds and following seas 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Safety………………………………………………………………………… 4 Quick Start ....................................................................................................... 5 Boat Operation ................................................................................................ 9 Engine Inspection ........................................................................................ 9 Start-Up ........................................................................................................ 12 Shutdown .................................................................................................... -

Alicia Undersea Life, to Preserve a Scenic Subtropical Setting, and to Provide an Outstanding Spot for Recreation and 1883 - 1905 Relaxation

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior LOCATION Biscayne Biscayne National Park Biscayne National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Biscayne National Park Maritime Heritage Trail Biscayne National Park was established as a national monument in 1968. In 1980 it was expanded to its current size of 173,000 acres and designated a national park to protect a rare combination of terrestrial and Alicia undersea life, to preserve a scenic subtropical setting, and to provide an outstanding spot for recreation and 1883 - 1905 relaxation. The park is dedicated to the preservation and public enjoyment of natural and cultural resources. Visit us online at: www.nps.gov/bisc The Florida Public Archaeology Network is dedicated to the protection of cultural resources, both on land Alicia aground on Long Reef with salvors at work. (Image courtesy of the and underwater, and to involving the public in the study Mariners’ Museum) of their past. Regional centers around Florida serve as clearinghouses for information, institutions for learning and training, and headquarters for public participation in archaeology. Find out more at: www.fl publicarchaeology.org 25º 24.705N 80º 7.660W Alicia SITE PLAN (1883 - 1905) History The steamer Alicia, owned by Linea de Vapres Serra in wrecking procedures, including many uncorked bottles seen Hawsehole from Bilboa, Spain, left Liverpool, England, in early April fl oating in the sea. 1905 bound for Havana. Her cargo was valued at greater than one million dollars and included fi ne silks, linens, On April 25, the tugboat Three Friends, captained by Harry silverware, household furniture, machetes, paint, pianos, Fozzard, attempted to pull Alicia off the reef. -

San Felipe: Step by Step Pack 6 ™

SAN FELIPE: Step by Step Pack 6 ™ Your parts Framing Tools and equipment Glue Superglue Knife Tweezers Sandpaper Clear varnish a Retrieve the grating that you assembled on Page 100. Cut two pieces of 2 x 3 mm wooden strip to fit across the width of the grating, and glue them in place as shown in the photograph, with their 2-mm sides in contact with the grating. b Cut a further six lengths and glue them as shown. 241 SAN FELIPE: Step by Step ™ c Round the corners of the strips, as shown in the photo. d Sand over the surface of the grating assembly so that it is smooth and level. Use a clear varnish as a finish for the grating. e Glue the grating assembly over the hatch aft of the capstan. 242 SAN FELIPE: Step by Step ™ f To create the stanchions, take a 2 x 3 mm wooden strip and shape one end to a slight diagonal. g Measure the distance between the deck and the top of the bulwark and cut the wooden strip from the last step to this length, measuring to the tip of the diagonal end. Then glue it into place midway between two gun ports, with the diagonal end nearest the top of the bulwark. Cut and shape a further three stanchions to fit on the main deck, and glue them into place between the gun ports. h Cut and glue another length to fit on the quarter deck, covering the join between the bulwarks. 243 SAN FELIPE: Step by Step ™ i Cut, shape and glue another two stanchions, to fit between the circular gun ports on the quarterdeck j Prepare another stanchion and glue it in line with the edging on the poop deck (red-dotted line). -

Operations Manual

GRATITUDE OPERATIONS MANUAL Welcome aboard! We are happy you have chosen Gratitude for your vacation. We are sure you will enjoy cruising the wonderful islands of the Pacific Northwest. This Manual, along with the Charter Reminders sheet will help you become familiar with the boat. This will make your vacation more enjoyable and trouble free. If you have questions about the boat or about places to visit, please do not hesitate to ask any of the AYC staff. We wish you fair winds and following seas! 1 5/11/2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Safety ................................................................................................................ 4 Mechanical Issues ............................................................................................ 4 Quick Start ....................................................................................................... 5 Boat Operation Engine Inspection ........................................................................................ 9 Start-Up ........................................................................................................ 12 Before Leaving Dock ................................................................................... 14 Getting Underway ........................................................................................ 14 Cruising ........................................................................................................ 14 Docking ....................................................................................................... -

Handling Storms at Sea : the Five Secrets of Heavy Weather Sailing

HANDLING STORMS AT SEA Overleaf: What is blue-water sailing really like when it’s stormy and big seas are running? Here’s my Santa Cruz 50 hurrying eastward near Marion Island in the Southern Ocean. The ever-faithful windvane is steering nicely while I play with the mainsail reefs and adjust the sails as the boat races through the water and makes great whooshing sounds as she surfs forward on a wave. You know that the yacht will rise up as the next crest comes, but sometimes you wonder if she is buoyant enough. You take a deep breath and say a silent prayer. ALSO BY HAL ROTH Pathway in the Sky (1965) Two on a Big Ocean (1972) After 50,000 Miles (1977) Two Against Cape Horn (1978) The Longest Race (1983) Always a Distant Anchorage (1988) Chasing the Long Rainbow (1990) Chasing the Wind (1994) We Followed Odysseus (1999) How to Sail Around the World (2004) The Hal Roth Seafaring Trilogy (2006) HANDLING STORMS AT SEA The 5 Secrets of Heavy Weather Sailing Hal Roth INTERNATIONAL MARINE / MCGRAW-HILL CAMDEN, MAINE • NEW YORK • CHICAGO • SAN FRANCISCO • LISBON • LONDON • MADRID • MEXICO CITY • MILAN • NEW DELHI • SAN JUAN • SEOUL • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TORONTO Copyright © 2009 by Hal Roth. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-07-164345-0 MHID: 0-07-164345-1 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-149648-3, MHID: 0-07-149648-3. -

![Thomas C. Byron's Narrative of the Cruises of the U.S. Frigate Constitution USS Constitution Museum Collection [1294.1] © 2018 USS Constitution Museum](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4544/thomas-c-byrons-narrative-of-the-cruises-of-the-u-s-frigate-constitution-uss-constitution-museum-collection-1294-1-%C2%A9-2018-uss-constitution-museum-4684544.webp)

Thomas C. Byron's Narrative of the Cruises of the U.S. Frigate Constitution USS Constitution Museum Collection [1294.1] © 2018 USS Constitution Museum

TRANSCRIPTION OF Thomas C. Byron’s Narrative of the Cruises of the U.S. Frigate Constitution USS Constitution Museum Collection [1294.1] © 2018 USS Constitution Museum | usscm.org Narrative of the Cruises of the U.S. Frigate Constitution By Thomas C. Byron Charlestown January 1861. On the return of the Constitution from France, Captain Haraden then Captain of the Yard overhauled her and put her in sailing order for Captain Hull, he having sailed in her before. We took in river water for the cruise and provisions and dropped down to Alexandria where we lay when the Declaration of War was read on board the officers and crew giving three cheers, shouting a gold chain or a wooden leg, this was the spirit of that noble crew. The next morning we dropped down the river and on the 4th of July lay at Annapolis where we fired at a target with large and small guns. Next morning we sailed for Boston and when crossing Nantucket Shoals fell in with a Brittish squadron seven in number, the african sixty four, Guerriere, Shannon, Belvidere, Eolus, & Trinadis. I believe we fell in with them in the night, the next morning it was calm and foggy and they were not more than two thirds gun shot off. Captain Hull then said to his men, we are almost surrounded but before I will give up the Ship I will blow her up and go with her; we then give three cheers and the Captain ordered the pursers Steward to bring up bread butter and cheese on the quarter Deck. -

Keith N. Meverden and Tamara L. Thomsen

Wisconsin’s Cross-Planked Mosquito Fleet: Underwater Archaeological Investigations of the Scow Schooners Iris, Ocean Wave, and Tennie and Laura State Archaeology and Maritime Preservation Program Technical Report Series #06-001 Keith N. Meverden and Tamara L. Thomsen Funded by the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA05NOS4191067, and the Wisconsin Department of Transportation Enhancements program. Additional support was provided by the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute. This report was prepared by the Wisconsin Historical Society under award # 86003- 006.29 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, and under award # 5101-02-75 from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, or the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute. Cover photo: Wreck of the scow schooner Ocean Wave in 110 feet of water off Sevastopol, Wisconsin. Photo by Tamara Thomsen. Copyright © 2005 by Wisconsin Historical Society All rights reserved CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS….………………..………………….. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS….…………………………… vi Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………. 1 Research Design and Methodology…………………. 3 Lake Michigan’s Maritime Economy……………….. 5 2. THE SCOW SCHOONER…………………………… … 8 3. SCOW SCHOONER IRIS………………………………. 13 Historical Background……………………………….. 13 Description of Field Research and Findings…………. 21 Conclusions and Recommendations…………………. 28 4. SCOW SCHOONER OCEAN WAVE.…………………… 30 Historical Background ………………………………. 30 Description of Field Research and Findings…………. 32 Conclusions and Recommendations…………………. -

Contents 2005-#2

DIY boat owner 2005-#2 www.diy-boat.com 1-888-658-2628 contents 2005-#2 columns 18 18 Core Doctor 7 SCUTTLeBUTT Balsa, plastic foam and plywood cored There’s Truth in Numbers: Every boat decks and hulls can be slowly poisoned sold is assigned a hull identification by the insidious infiltration of minute number that gives the buyer a clue to amounts of water over the years. You the boat’s builder and true age. Here’s how to crack the code. By Patricia can avoid problems by applying proper Kearns techniques to install new hardware and 30 ELECTRIcAL reseal any leaking hardware now. By Batteries and Charging FAQ: John Nick Bailey Payne, DIY’s electrical advisor provides solutions to questions submitted to 42 DIY’s Technical Helpline concerning 26 A Calculated batteries, battery switches and charging Approach To Proper systems. Gear Ratios 33 ELECTRONICS All About Transducers: Here’s what you Many modern diesels available for dis- need to know about the construction, placement powerboats and sailboats selection, installation, routine mainte- are offered with transmission and gear nance and troubleshooting tips of depth, ratio options. Follow these steps to speed, windspeed and wind direction determine the proper engine power rat- transducers. By John Payne ing, transmission gear ratio, propeller 37 SAILBoAt RIGGInG diameter and shaft diameter for your The Shape of Speed: Whether you’re a 51 novice or veteran sailor, you’re sure to boat. By Robert Hess gain some useful information about how to set your sails for various wind condi- tions. By Roger Marshall 42 Boat Owner’s 5 PoWeRBoAt RIGGInG Guide To Used Boats Is There A Sterndrive Repower In Your If you’re going to invest in a boat that Future?: Replacing the engines in an needs renovating, you will recover more older boat may just be the better option of your investment, in both dollars and than purchasing a new boat. -

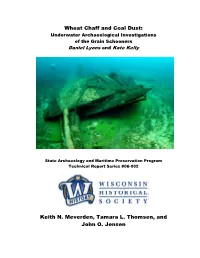

Keith N. Meverden, Tamara L. Thomsen, and John O. Jensen

Wheat Chaff and Coal Dust: Underwater Archaeological Investigations of the Grain Schooners Daniel Lyons and Kate Kelly State Archaeology and Maritime Preservation Program Technical Report Series #06-002 Keith N. Meverden, Tamara L. Thomsen, and John O. Jensen Funded by the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute and the National Sea Grant College Program, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, and the State of Wisconsin, Grant # NA16RG2257; the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management under the Coastal Zone Management Act, Grant # NA03NOS4190106, and the Wisconsin Department of Transportation Enhancements program. This report was prepared by the Wisconsin Historical Society under award # C/C-7 from the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, award # 84003-004.21 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, and under award # 5101-02-75 from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Department of Commerce, the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, or the National Sea Grant College Program. The Daniel Lyons was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on 3 October 2007. The Kate Kelly was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on 21 November 2007. Cover photo: The Daniel Lyons’ bow in 110 feet of water, nine miles northeast of Algoma, Wisconsin. Photo by Tamara Thomsen. Copyright © 2006 by Wisconsin Historical Society All rights reserved CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS…………………..……………………..