U.S. Shipping and Shipbuilding: Trends and Policy Choices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hidden Cargo: a Cautionary Tale About Agroterrorism and the Safety of Imported Produce

HIDDEN CARGO: A CAUTIONARY TALE ABOUT AGROTERRORISM AND THE SAFETY OF IMPORTED PRODUCE 1. INTRODUCTION The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on Septem ber 11, 2001 ("9/11") demonstrated to the United States ("U.S.") Gov ernment the U.S. is vulnerable to a wide range of potential terrorist at tacks. l The anthrax attacks that occurred immediately following the 9/11 attacks further demonstrated the vulnerability of the U.S. to biological attacks. 2 The U.S. Government was forced to accept its citizens were vulnerable to attacks within its own borders and the concern of almost every branch of government turned its focus toward reducing this vulner ability.3 Of the potential attacks that could occur, we should be the most concerned with biological attacks on our food supply. These attacks are relatively easy to initiate and can cause serious political and economic devastation within the victim nation. 4 Generally, acts of deliberate contamination of food with biological agents in a terrorist act are defined as "bioterrorism."5 The World Health Organization ("WHO") uses the term "food terrorism" which it defines as "an act or threat of deliberate contamination of food for human con- I Rona Hirschberg, John La Montagne & Anthony Fauci, Biomedical Research - An Integral Component of National Security, NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE (May 20,2004), at 2119, available at http://contenLnejrn.org/cgi/reprint/350/2112ll9.pdf (dis cussing the vulnerability of the U.S. to biological, chemical, nuclear, and radiological terrorist attacks). 2 Id.; Anthony Fauci, Biodefence on the Research Agenda, NATURE, Feb. -

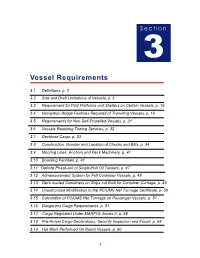

Section 3 2018 Edition

S e c ti o n 3 Vessel Requirements 3.1 Definitions, p. 2 3.2 Size and Draft Limitations of Vessels, p. 4 3.3 Requirement for Pilot Platforms and Shelters on Certain Vessels, p. 16 3.4 Navigation Bridge Features Required of Transiting Vessels, p. 19 3.5 Requirements for Non-Self-Propelled Vessels, p. 31 3.6 Vessels Requiring Towing Services, p. 32 3.7 Deckload Cargo, p. 33 3.8 Construction, Number and Location of Chocks and Bitts, p. 34 3.9 Mooring Lines, Anchors and Deck Machinery, p. 41 3.10 Boarding Facilities, p. 41 3.11 Definite Phase-out of Single-Hull Oil Tankers, p. 47 3.12 Admeasurement System for Full Container Vessels, p. 48 3.13 Deck-loaded Containers on Ships not Built for Container Carriage, p. 49 3.14 Unauthorized Modification to the PC/UMS Net Tonnage Certificate, p. 50 3.15 Calculation of PC/UMS Net Tonnage on Passenger Vessels, p. 51 3.16 Dangerous Cargo Requirements, p. 51 3.17 Cargo Regulated Under MARPOL Annex II, p. 58 3.18 Pre-Arrival Cargo Declarations, Security Inspection and Escort, p. 58 3.19 Hot Work Performed On Board Vessels, p. 60 1 OP Operations Manual Section 3 2018 Edition 3.20 Manning Requirements, p. 61 3.21 Additional Pilots Due to Vessel Deficiencies, p. 62 3.22 Pilot Accommodations Aboard Transiting Vessels, p. 63 3.23 Main Source of Electric Power, p. 63 3.24 Emergency Source of Electrical Power, p. 63 3.25 Sanitary Facilities and Sewage Handling, p. -

In-Transit Cargo Crime Impacting the Retail Supply Chain

Journal of Transportation Management Volume 29 Issue 1 Article 4 7-1-2018 In-transit cargo crime impacting the retail supply chain John Tabor National Retail Systems, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/jotm Part of the Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, and the Transportation Commons Recommended Citation Tabor, John. (2018). In-transit cargo crime impacting the retail supply chain. Journal of Transportation Management, 29(1), 27-34. doi: 10.22237/jotm/1530446580 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Transportation Management by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. IN-TRANSIT CARGO CRIME IMPACTING THE RETAIL SUPPLY CHAIN John Tabor1 National Retail Systems, Inc. ABSTRACT Surveys of retail security directors show that almost half of those polled had been the victims of a supply- chain disruption directly related to cargo theft. This is a significant increase from just five years ago. In order to fully understand the issue of cargo theft, retailers need to know why it exists, who is perpetrating it, how risk can be reduced, and ultimately how to react to a loss. This article explores a number of dimensions of the issue, and offers several suggestions for mitigating the risk and dealing with theft after it occurs. INTRODUCTION That said, remember that virtually 100 percent of the merchandise in retail stores is delivered by truck. Surveys of retail security directors showed that In many cases the only two preventative measures almost half of those polled had been the victims of a put in place to secure that same merchandise in supply-chain disruption directly related to cargo transit is a key to the tractor and a seal on the rear theft. -

New Insurance for Newbuildi

The Swedish Club Letter 2–2006 Insurance New Insurance for Newbuildi ■■ The Swedish Club is one of very few marine insurance companies that offer a range of products Tord Nilsson broad enough to cover most of the needs of ship- Area Manager owners. Team Göteborg I We will soon complement the products we have by adding an insurance that specifi cally targets the needs of shipowners with newbuildings on order. Our fi rst contact with owners has traditionally been when they have started to look for suppliers of H&M, P&I Cover for liabilities in respect and FD&D insurances. We do in some cases cover FD&D for newbuildings and of superintendents and for the crew whilst travelling to and from the shipyard just prior to delivery. We feel that owners need to start looking at their insurable interests long other shipowners’ personnel before delivery, as there are risks relating to the newbuilding that could affect attending at newbuildings owners adversely. Only a few owners currently do this. Our Newbuilding Risks Insurance is one product and it encompasses three areas: 1. Cover for liabilities in respect of superintendents and other shipowners’ ■■ personnel attending newbuildings. The P&I cover 1that can be offered by a This insurance includes liabilities under the terms of the employment contract to club in the Internatio- Annica Börjesson pay damages or compensation for personal injury, illness or death of the superin- nal Group is ultimately Claims Executive tendent whilst attending the NB site or travelling to and from the site. regulated by the Poo- Team Göteborg I < Hospital, medical, repatriation, funeral or other expenses necessarily incurred ling Agreement, “the in relation to the superintendent whilst attending the NB site. -

Air Cargo E-Commerce & COVID-19 Impact

52%of consumers bought more online during the COVID-19 crisis 74%growth in global online retail sales average transaction volumes in March compared with the same period last year 200%growth in online sales of home appliances, Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) and food and health products • Shifts on international trade, as border restrictions place the focus An opportunity for transformation on local purchasing. Air cargo e-commerce and COVID-19 impact • Software-driven process chang- es, including artificial intelligence (AI) and the internet of things (IoT), as Since early March, we have seen e-Commerce: key for air cargo social distancing and business-conti- how COVID-19 has changed the In 2019, e-Commerce only repre- nuity needs accelerate their develop- world. It forced governments to sented 14% of the total retail sales. ment. close borders and take drastic This means there is much room for • Shifts in markets’ domestic measures to protect people and growth as consumers continue to commerce, driven by changing ensure essential services. The ban move online. In the last year, IATA consumer behaviors and the growth on social gatherings, the closing of studied whether the air cargo supply of e-commerce. stores, restaurants, grocery shops, chain was ready for this tsunami of gardening centers, theatres and parcels and how airlines could adapt • Machine-driven process changes, concerts have led consumers to live to benefit from this growth. as the perception of investments in their lives online, including shop- automation improves, speeding up The annual value of global e-com- ping. its development. merce sales of goods reached 2 In September, IPC reported that more trillion USD and was forecasted to Building supply chain resilience than half of consumers bought more exceed 4.4 trillion by 2025. -

Visualitza/Obre

HOW THE INDUSTRY 4.0 COULD AFFECT THE SHIPBUILDING WORLD Rodrigo Pérez Fernández, [email protected], correspondence author SENER, Madrid/Spain. C/ Severo Ochoa, 4 - 28760 Tres Cantos - Madrid (Spain) Abstract The marine structures are developed with Computer Aided Design (CAD) platforms, but every day we are looking for integrated development of the product involving all its Life Cycle. CAD system integrated with Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) and from the PLM we can conceive all the design but also control the production and include the use of the vessel. The PLM can contain information of all systems of the vessel and also all its components. If the components are designed for the Internet of Ships (IoS) it will have technology that allows to share their situation, diagnosis, functionality with the PLM system which distributes the initial design. The PLM system can use this information for knowing whether they are working properly or if we can improve its performance. It is also possible to identify whether it is necessary to make maintenance of the object or if it is necessary to replace it because its life ends or because it's working wrongly. It will be possible to determine and evaluate its performance comparing to other similar components or comparing to it different operating periods. It will also be possible to know how their performance affects the functioning of the whole product, i.e., the vessel. Furthermore, if the connection of the objects is realized with its PLM, it would be possible to record their history status, make change tracking, and know what is its function or its performance after realizing programmed maintenance. -

Tar and Turpentine

ECONOMICHISTORY Tar and Turpentine BY BETTY JOYCE NASH Tarheels extract the South’s first industry turdy, towering, and fire-resistant longleaf pine trees covered 90 million coastal acres in colonial times, Sstretching some 150,000 square miles from Norfolk, Va., to Florida, and west along the Gulf Coast to Texas. Four hundred years later, a scant 3 percent of what was known as “the great piney woods” remains. The trees’ abundance grew the Southeast’s first major industry, one that served the world’s biggest fleet, the British Navy, with the naval stores essential to shipbuilding and maintenance. The pines yielded gum resin, rosin, pitch, tar, and turpentine. On oceangoing ships, pitch and tar Wilmington, N.C., was a hub for the naval stores industry. caulked seams, plugged leaks, and preserved ropes and This photograph depicts barrels at the Worth and Worth rosin yard and landing in 1873. rigging so they wouldn’t rot in the salty air. Nations depended on these goods. “Without them, and barrels in 1698. To stimulate naval stores production, in 1704 without access to the forests from which they came, a Britain offered the colonies an incentive, known as a bounty. nation’s military and commercial fleets were useless and its Parliament’s “Act for Encouraging the Importation of Naval ambitions fruitless,” author Lawrence Earley notes in his Stores from America” helped defray the eight-pounds- book Looking for Longleaf: The Rise and Fall of an American per-ton shipping cost at a rate of four pounds a ton on tar Forest. and pitch and three pounds on rosin and turpentine. -

Promoting Logistics Development in Rural Areas

Promoting Logistics Development in Rural Areas Logistics plays an important role in agricultural production and supply-chain management, ultimately enhancing food safety and quality. Improvements in rural logistics help farmers to harvest and market crops more e ciently; and by facilitating communication, they serve to expand the markets for agricultural products. While recognizing the rapidly changing rural landscape in the People’s Republic of China, the distribution of goods is still impeded, and the quality of services poor. This study is part of the Asian Development Bank’s initiative to support and promote the development of the agriculture sector and establish e cient rural–urban synergies. Read how the private and public sectors can improve and promote logistics development in rural areas. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacifi c region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to a large share of the world’s poor. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by members, including from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. PROMOTING LOGISTICS DEVELOPMENT IN RURAL AREAS ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila. Philippines 9 789292 579913 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org PROMOTING LOGISTICS DEVELOPMENT IN RURAL AREAS ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2017 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. -

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding A promising rst half, an uncertain second one 2018 started briskly in the wake of 2017. In the rst half of the year, newbuilding orders were placed at a rate of about 10m dwt per month. However the pace dropped in the second half, as owners grappled with a rise in newbuilding prices and growing uncertainty over the IMO 2020 deadline. Regardless, newbuilding orders rose to 95.5m dwt in 2018 versus 83.1m dwt in 2017. Demand for bulkers, container carriers and specialised ships increased, while for tankers it receded, re ecting low freight rates and poor sentiment. Thanks to this additional demand, shipbuilders succeeded in raising newbuilding prices by about 10%. This enabled them to pass on some of the additional building costs resulting from higher steel prices, new regulations and increased pressure from marine suppliers, who have also been struggling since 2008. VIIKKI LNG-fuelled forest product carrier, 25,600 dwt (B.Delta 25), built in 2018 by China’s Jinling for Finland’s ESL Shipping. 5 Orders Million dwt 300 250 200 150 100 50 SHIPBUILDING SHIPBUILDING KEY POINTS OF 2018 KEY POINTS OF 2018 0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Deliveries vs demolitions Fleet evolution Deliveries Demolitions Fleet KEY POINTS OF 2018 Summary 2017 2018 Million dwt Million dwt Million dwt Million dwt Ships 1,000 1,245 Orders 200 2,000 m dwt 83.1 95.5 180 The three Asian shipbuilding giants, representing almost 95% of the global 1,800 orderbook by deadweight, continued to ght ercely for market share. -

ONI-54-A.Pdf

r~us U. S. FLEET TRAIN- Division cf Naval Intelligence-Identification and Characteristics Section e AD Destroyer Tenders Page AP Troop Transports Pa g e t Wo "'W" i "~ p. 4-5 z MELVILLE 28 5 BURROWS 14 3, 4 DOBBIN Class 4 7 WHARTON 9 9 BLACK HAWK 28 21, 22 WAKEFIELD Class 12 11, 12 ALTAIR Class 28 23 WEST POINT 13 14, 15, 17-19 DIXIE Class 7 24 ORIZABA 13 16 CASCADE 10 29 U. S. GRANT 14 20,21 HAMUL Class 22 31, 3Z CHATEAU THIERRY Class 9 33 REPUBLIC 14 AS Submarine Tenders 41 STRATFORD 14 3 HOLLAND 5 54, 61 HERMIT AGE Class 13 5 BEAVER 16 63 ROCHAMBEAU 12 11, 12, 15 19 FULTON Class 7 67 DOROTHEA L. DIX 25 Sin a ll p. H 13, 14 GRIFFIN Class 22 69- 71,76 ELIZ . STANTON Cla ss 23 20 OTUS 26 72 SUSAN B. ANTHONY 15 21 AN TEA US 16 75 GEMINI 17 77 THURSTON 20 AR Repair Ships 110- "GENERAL" Class 10 1 MEDUSA 5 W orld W ar I types p. 9 3, 4 PROMETHEUS Class 28 APA Attack Transports 5- VULCAN Class 7 1, 11 DOYEN Class 30 e 9, 12 DELTA Class 22 2, 3, 12, 14- 17 HARRIS Class 9 10 ALCOR 14 4, 5 McCAWLEY , BARNETT 15 11 RIGEL 28 6-9 HEYWOOD Class 15 ARH Hull Repair Ships 10, 23 HARRY LEE Class 14 Maritime types p. 10-11 13 J T. DICKMAN 9 1 JASON 7 18-zo; 29, 30 PRESIDENT Class 10 21, 28, 31, 32 CRESCENT CITY Class 11 . -

China's Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations

China’s Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations The modular transfer system between a Type 054A frigate and a COSCO container ship during China’s first military-civil UNREP. Source: “重大突破!民船为海军水面舰艇实施干货补给 [Breakthrough! Civil Ships Implement Dry Cargo Supply for Naval Surface Ships],” Guancha, November 15, 2019 Primary author: Chad Peltier Supporting analysts: Tate Nurkin and Sean O’Connor Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 113-291. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. 1 Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology, Scope, and Study Limitations ........................................................................................................ 6 1. China’s Expeditionary Operations -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy.