Report on Forest Research 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Hymenoptera, Tenthredinidae) – a New Pest Species of Ash Tree in the Republic of Moldova

Muzeul Olteniei Craiova. Oltenia. Studii şi comunicări. Ştiinţele Naturii. Tom. 36, No. 1/2020 ISSN 1454-6914 Tomostethus nigritus F. (HYMENOPTERA, TENTHREDINIDAE) – A NEW PEST SPECIES OF ASH TREE IN THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA MOCREAC Nadejda Abstract. In the Republic of Moldova, the ash tree is a common forest species, used in the reforestation and afforestation of woods and territories, and widely used as an ornamental tree in cities and along roads. For more than ten years, our ash tree woods have been severely defoliated by the ash weevil Stereonychusfraxini (De Geer, 1775) from Curculionidae family. In the vegetation period of 2018 and 2019, defoliation was seen on ash trees, caused by unknown sawfly larvae species from the Tenthredinidae family. The analyses showed that these pests belong to the Hymenoptera order – the privet sawfly – Macrophya punctumalbum (Linnaeus, 1767), and Tomostethus nigritus (Fabricius, 1804), the last one being a new species for the fauna of the Republic of Moldova. The biggest ash defoliations caused by the Tomostethus nigritus larvae were recorded in the centre of the country, especially in the Nisporeni and Tighina Forest Enterprises and in the “Plaiul Fagului” Scientific Reserve, as well as in the urban space. Keywords: Ash Black sawfly, Tenthredinidae, ash tree, outbreaks, defoliations, Republic of Moldova. Rezumat. Tomostethus nigritus F. (Hymenoptera, Tenthredinidae) – specie nouă de dăunător al frasinului în Republica Moldova. În Republica Moldova, frasinul este o specie obișnuită, folosită nu numai în reîmpădurire și împădurire dar utilizat pe scară largă ca arbore ornamental în parcurile din orașe și de-a lungul drumurilor. Mai bine de zece ani, pădurile de frasin sunt defoliate anual de către trombarul frunzelor de frasin Stereonychus fraxini (De Geer, 1775) din familia Curculionidae. -

Alnus Glutinosa

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.13.875229; this version posted December 13, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Investigations into the declining health of alder (Alnus glutinosa) along the river Lagan in Belfast, including the first report of Phytophthora lacustris causing disease of Alnus in Northern Ireland Richard O Hanlon (1, 2)* Julia Wilson (2), Deborah Cox (1) (1) Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute, Belfast, BT9 5PX, Northern Ireland, UK. (2) Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK * [email protected] Additional key words: Plant health, Forest pathology, riparian, root and collar rot. Abstract Common alder (Alnus glutinosa) is an important tree species, especially in riparian and wet habitats. Alder is very common across Ireland and Northern Ireland, and provides a wide range of ecosystem services. Surveys along the river Lagan in Belfast, Northern Ireland led to the detection of several diseased Alnus trees. As it is known that Alnus suffers from a Phytophthora induced decline, this research set out to identify the presence and scale of the risk to Alnus health from Phytophthora and other closely related oomycetes. Sampling and a combination of morphological and molecular testing of symptomatic plant material and river baits identified the presence of several Phytophthora species, including Phytophthora lacustris. A survey of the tree vegetation along an 8.5 km stretch of the river revealed that of the 166 Alnus trees counted, 28 were severely defoliated/diseased and 9 were dead. -

New Data on the Occurence of Horntails in Poland (Hymenoptera, Symphyta: Siricidae)

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 136 (2019) 241-246 EISSN 2392-2192 SHORT COMMUNICATION New data on the occurence of horntails in Poland (Hymenoptera, Symphyta: Siricidae) Borowski Jerzy1,*, Marczak Dawid2, Szawaryn Karol3, Kwiatkowski Adam4, Cieślak Rafał1, Buchholz Lech5 1Department of Forest Protection and Ecology, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, ul. Nowoursynowska 159/34, 02-776 Warsaw, Poland 2Kampinos National Park, ul. Tetmajera 38, 05-080 Izabelin, Poland University of Ecology and Management in Warsaw, ul. Olszewska 12, 00-792 Warsaw, Poland 3Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences, ul. Wilcza 64, 00-679 Warsaw, Poland 4Regional Directorate of the State Forests in Białystok, ul. Lipowa 51, 15-424 Białystok, Poland Bialystok University of Technology, ul. Wiejska 54A, 15-351 Białystok, Poland 5Świętokrzyski National Park, ul. Suchedniowska 4, 26-010 Bodzentyn, Poland *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT The paper presents new data on the occurrence of 6 sawflies species of the Siricidae family, on the territory of Poland. New faunistic data was supplemented with elements of bionomics and information on geographical distribution of particular species. Keywords: Hymenoptera, Symphyta, sawflies, Siricidae, funistic data, Poland ( Received 28 September 2019; Accepted 10 October 2019; Date of Publication 15 October 2019 ) World Scientific News 136 (2019) 241-246 INTRODUCTION Horntails (Siricidae) is one of Symphyta families rather poor in species number, represented in Poland by 10 species (Borowski & al. 2019). Most of them are trophically connected with coniferous trees, while only the species of Tremex Jurine genus live on deciduous trees. Horntails are classified as xylophages, i.e. the insects whose total development, from egg laying to the occurrence of imagines, takes place in wood. -

THE SIRICID WOOD WASPS of CALIFORNIA (Hymenoptera: Symphyta)

Uroce r us californ ic us Nott on, f ema 1e. BULLETIN OF THE CALIFORNIA INSECT SURVEY VOLUME 6, NO. 4 THE SIRICID WOOD WASPS OF CALIFORNIA (Hymenoptera: Symphyta) BY WOODROW W. MIDDLEKAUFF (Department of Entomology and Parasitology, University of California, Berkeley) UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1960 BULLETIN OF THE CALIFORNIA INSECT SURVEY Editors: E. G: Linsley, S. B. Freeborn, P. D. Hurd, R. L. Usinget Volume 6, No. 4, pp. 59-78, plates 4-5, frontis. Submitted by editors October 14, 1958 Issued April 22, 1960 Price, 50 cents UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES CALIFORNIA CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON, ENGLAND PRINTED BY OFFSET IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA THE SIRICID WOOD WASPS OF CALIFORNIA (Hymenoptera: Symphyta) BY WOODROW W. MIDDLEKAUFF INTRODUCTION carpeting. Their powerful mandibles can even cut through lead sheathing. The siricid wood wasps are fairly large, cylin- These insects are widely disseminated by drical insects; usually 20 mm. or more in shipments of infested lumber or timber, and length with the head, thorax, and abdomen of the adults may not emerge until several years equal width. The antennae are long and fili- have elapsed. Movement of this lumber and form, with 14 to 30 segments. The tegulae are timber tends to complicate an understanding minute. Jn the female the last segment of the of the normal distribution pattern of the spe- abdomen bears a hornlike projection called cies. the cornus (fig. 8), whose configuration is The Nearctic species in the family were useful for taxonomic purposes. This distinc- monographed by Bradley (1913). -

Insects That Feed on Trees and Shrubs

INSECTS THAT FEED ON COLORADO TREES AND SHRUBS1 Whitney Cranshaw David Leatherman Boris Kondratieff Bulletin 506A TABLE OF CONTENTS DEFOLIATORS .................................................... 8 Leaf Feeding Caterpillars .............................................. 8 Cecropia Moth ................................................ 8 Polyphemus Moth ............................................. 9 Nevada Buck Moth ............................................. 9 Pandora Moth ............................................... 10 Io Moth .................................................... 10 Fall Webworm ............................................... 11 Tiger Moth ................................................. 12 American Dagger Moth ......................................... 13 Redhumped Caterpillar ......................................... 13 Achemon Sphinx ............................................. 14 Table 1. Common sphinx moths of Colorado .......................... 14 Douglas-fir Tussock Moth ....................................... 15 1. Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University Cooperative Extension etnomologist and associate professor, entomology; David Leatherman, entomologist, Colorado State Forest Service; Boris Kondratieff, associate professor, entomology. 8/93. ©Colorado State University Cooperative Extension. 1994. For more information, contact your county Cooperative Extension office. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, -

Commodity Risk Assessment of Black Pine (Pinus Thunbergii Parl.) Bonsai from Japan

SCIENTIFIC OPINION ADOPTED: 28 March 2019 doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5667 Commodity risk assessment of black pine (Pinus thunbergii Parl.) bonsai from Japan EFSA Panel on Plant Health (EFSA PLH Panel), Claude Bragard, Katharina Dehnen-Schmutz, Francesco Di Serio, Paolo Gonthier, Marie-Agnes Jacques, Josep Anton Jaques Miret, Annemarie Fejer Justesen, Alan MacLeod, Christer Sven Magnusson, Panagiotis Milonas, Juan A Navas-Cortes, Stephen Parnell, Philippe Lucien Reignault, Hans-Hermann Thulke, Wopke Van der Werf, Antonio Vicent Civera, Jonathan Yuen, Lucia Zappala, Andrea Battisti, Anna Maria Vettraino, Renata Leuschner, Olaf Mosbach-Schulz, Maria Chiara Rosace and Roel Potting Abstract The EFSA Panel on Plant health was requested to deliver a scientific opinion on how far the existing requirements for the bonsai pine species subject to derogation in Commission Decision 2002/887/EC would cover all plant health risks from black pine (Pinus thunbergii Parl.) bonsai (the commodity defined in the EU legislation as naturally or artificially dwarfed plants) imported from Japan, taking into account the available scientific information, including the technical information provided by Japan. The relevance of an EU-regulated pest for this opinion was based on: (a) evidence of the presence of the pest in Japan; (b) evidence that P. thunbergii is a host of the pest and (c) evidence that the pest can be associated with the commodity. Sixteen pests that fulfilled all three criteria were selected for further evaluation. The relevance of other pests present in Japan (not regulated in the EU) for this opinion was based on (i) evidence of the absence of the pest in the EU; (ii) evidence that P. -

Taxonomic Groups of Insects, Mites and Spiders

List Supplemental Information Content Taxonomic Groups of Insects, Mites and Spiders Pests of trees and shrubs Class Arachnida, Spiders and mites elm bark beetle, smaller European Scolytus multistriatus Order Acari, Mites and ticks elm bark beetle, native Hylurgopinus rufipes pine bark engraver, Ips pini Family Eriophyidae, Leaf vagrant, gall, erinea, rust, or pine shoot beetle, Tomicus piniperda eriophyid mites ash flower gall mite, Aceria fraxiniflora Order Hemiptera, True bugs, aphids, and scales elm eriophyid mite, Aceria parulmi Family Adelgidae, Pine and spruce aphids eriophyid mites, several species Cooley spruce gall adelgid, Adelges cooleyi hemlock rust mite, Nalepella tsugifoliae Eastern spruce gall adelgid, Adelges abietis maple spindlegall mite, Vasates aceriscrumena hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae maple velvet erineum gall, several species pine bark adelgid, Pineus strobi Family Tarsonemidae, Cyclamen and tarsonemid mites Family Aphididae, Aphids cyclamen mite, Phytonemus pallidus balsam twig aphid, Mindarus abietinus Family Tetranychidae, Freeranging, spider mites, honeysuckle witches’ broom aphid, tetranychid mites Hyadaphis tataricae boxwood spider mite, Eurytetranychus buxi white pine aphid, Cinara strobi clover mite, Bryobia praetiosa woolly alder aphid, Paraprociphilus tessellatus European red mite, Panonychus ulmi woolly apple aphid, Eriosoma lanigerum honeylocust spider mite, Eotetranychus multidigituli Family Cercopidae, Froghoppers or spittlebugs spruce spider mite, Oligonychus ununguis spittlebugs, several -

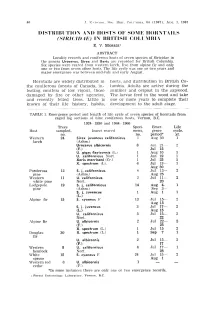

" ANI) HOSTS of SO"IE 1I0HNTAILS (SI Riel F)A F,,) in BH ITISII COLL'i BL\

00 .T . '·;'TO \lO I.. Se .... BIUT. CO I.I · \""A. 64 (1967)' A UG. 1. 1967 OISTHIBlTIO," ANI) HOSTS OF SO"IE 1I0HNTAILS (SI Riel f)A f,,) IN BH ITISII COLL'I BL\ E. V. MORRIS I ABSTRACT Locality recol'ds and con iferous hosts of seven species of Siricidae in the genera Urocerus, Sirex and Xeris are recorded for British Columbia. Six species were reared from western larch. fi ve from alpine fir and only one or two from seven other hosts. The life cycle was one or two years and major emergence was betw('('n mid-July ami early August. Horntails are widely dis tributed in hosts, and dis tribution in British Co the coniferous forests of Ca nada, in lumbia. Adults are active during the festing conifers of low vigour, those s ummer a nd ovipost in the sapwood. damaged by fire or other agencies, The la rvae fe ed in the wood and take and recently felled trees . Little is one or more years to complete their known of their life history, habits, development to the adult stage. TABLE 1. Emergence period and length of life cycle of sc' ven species of horn tails from caged log sections of nine coniferous hosts, Vernon, B.C. 1924 - 1930 and 1964 - 1966 Trees Speci Emer Life Host sampled, Insect reared mens, gence cycle, no. no. period* yr. Weste rn 24 Sirex iuvencus californicus 1 Aug 30 1 larch (Ashm. ) Urocerus albicornis 8 .Jun 21 ~ 2 (F.) Jul 15 U. gigas flavicornis (L.) 1 Aug 10 1 U. -

Functional Morphology of the Male Genitalia and Copulation in Lower

AZO094.fm Page 331 Wednesday, September 5, 2001 10:03 AM Acta Zoologica (Stockholm) 82: 331–349 (October 2001) FunctionalBlackwell Science Ltd morphology of the male genitalia and copulation in lower Hymenoptera, with special emphasis on the Tenthredinoidea s. str. (Insecta, Hymenoptera, ‘Symphyta’) Susanne Schulmeister Abstract Institut für Zoologie und Anthropologie, Schulmeister, S. 2001. Functional morphology of the male genitalia and Abteilung Systematik, Morphologie und copulation in lower Hymenoptera, with special emphasis on the Tenthredinoidea Evolutionsbiologie, Berliner Str. 28, s. str. (Insecta, Hymenoptera, ‘Symphyta’). — Acta Zoologica (Stockholm) 82: D–37073 Göttingen, Germany 331–349 Keywords: A general description of the male reproductive organs of lower Hymenoptera Hymenoptera, Tenthredinoidea, is given. The terminology of the male genitalia is revised. The male external morphology, male genitalia, copulation genitalia of Tenthredo campestris are treated in detail as a specific example of the morphology. The interaction of the male and female parts during copula- Accepted for publication: tion is described for Aglaostigma lichtwardti. The possible function of sclerites 5 April 2001 and muscles of the male copulatory organ of Tenthredinoidea s. str. is dis- cussed. Additional observations on morphology and function made in non- tenthredinoid lower Hymenoptera are included. The assumption that the gonomaculae act as suction cups is confirmed for the first time. The evolution of obligate and facultative strophandry is discussed. The stem species of all Hymenoptera was probably orthandrous and facultatively strophandrous. Susanne Schulmeister. Institute of Zoology, Berliner Str. 28, D–37073 Göttingen, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] tionships among Hymenoptera. This scarcity of male genital Introduction characters is due to the fact that a comparative analysis in a The lower Hymenoptera known as ‘Symphyta’ or sawflies phylogenetic context does not exist. -

The Potential Ecological Impact of Ash Dieback in the UK

JNCC Report No. 483 The potential ecological impact of ash dieback in the UK Mitchell, R.J., Bailey, S., Beaton, J.K., Bellamy, P.E., Brooker, R.W., Broome, A., Chetcuti, J., Eaton, S., Ellis, C.J., Farren, J., Gimona, A., Goldberg, E., Hall, J., Harmer, R., Hester, A.J., Hewison, R.L., Hodgetts, N.G., Hooper, R.J., Howe, L., Iason, G.R., Kerr, G., Littlewood, N.A., Morgan, V., Newey, S., Potts, J.M., Pozsgai, G., Ray, D., Sim, D.A., Stockan, J.A., Taylor, A.F.S. & Woodward, S. January 2014 © JNCC, Peterborough 2014 ISSN 0963 8091 For further information please contact: Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY www.jncc.defra.gov.uk This report should be cited as: Mitchell, R.J., Bailey, S., Beaton, J.K., Bellamy, P.E., Brooker, R.W., Broome, A., Chetcuti, J., Eaton, S., Ellis, C.J., Farren, J., Gimona, A., Goldberg, E., Hall, J., Harmer, R., Hester, A.J., Hewison, R.L., Hodgetts, N.G., Hooper, R.J., Howe, L., Iason, G.R., Kerr, G., Littlewood, N.A., Morgan, V., Newey, S., Potts, J.M., Pozsgai, G., Ray, D., Sim, D.A., Stockan, J.A., Taylor, A.F.S. & Woodward, S. 2014. The potential ecological impact of ash dieback in the UK. JNCC Report No. 483 Acknowledgements: We thank Keith Kirby for his valuable comments on vegetation change associated with ash dieback. For assistance, advice and comments on the invertebrate species involved in this review we would like to thank Richard Askew, John Badmin, Tristan Bantock, Joseph Botting, Sally Lucker, Chris Malumphy, Bernard Nau, Colin Plant, Mark Shaw, Alan Stewart and Alan Stubbs. -

Norwegian Journal of Entomology

Norwegian Journal of Entomology Volume 49 No. 2 • 2002 Published by the Norwegian Entomological Society Oslo and Stavanger NORWEGIAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGY A continuation ofFauna Norvegica Serie B (1979-1998), Norwegian Journal ofEntomology (1975-1978) and Norsk entomologisk Tidsskrift (1921-1974). Published by The Norwegian Entomological Society (Norsk ento mologisk forening). Norwegian Journal ofEntomologypublishes original papers and reviews on taxonomy, faunistics, zoogeography, general and applied ecology ofinsects and related terrestrial arthropods. Short communications, e.g. one or two printed pages, are also considered. Manuscripts should be sent to the editor. Editor Lauritz Semme, Department ofBiology, University ofOslo, P.O.Box 1050 Blindern, N-0316 Oslo, Norway. E mail: [email protected]. Editorial secretary Lars Ove Hansen, Zoological Museum, University of Oslo, P.O.Box 1172, Blindern, N-0318 Oslo. E-mail: [email protected]. Editorial board Ame C. Nilssen, Tromse John O. Solem, Trondheim Uta Greve Jensen, Bergen Knut Rognes, Stavanger Ame Fjellberg, Tjeme Membership and subscription. Requests about membership should be sent to the secretary: Jan A. Stenlekk, P.O. Box 386, NO-4002 Stavanger, Norway ([email protected]). Annual membership fees for The Norwegian Ento mological Society are as follows: NOK 200 (juniors NOK 100) for members with addresses in Norway, NOK 250 for members in Denmark, Finland and Sweden, NOK 300 for members outside Fennoscandia and Denmark. Members ofThe Norwegian Entomological Society receive Norwegian Journal ofEntomology and Insekt-Nytt free. Institutional and non-member subscription: NOK 250 in Fennoscandia and Denmark, NOK 300 elsewhere. Subscription and membership fees should be transferred in NOK directly to the account of The Norwegian Entomo logical Society, attn.: Egil Michaelsen, Kurlandvn. -

Other Invasive Tree Pathogens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aberdeen University Research Archive 6:RRGZDUG%DOWLF)RUHVWU\YRO ,661 Introduction Part 3: Other Invasive Tree Pathogens STEVE WOODWARD* University of Aberdeen, Institute of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Cruickshank Building, St. Machar Drive, Aberdeen AB24 3UU, Scotland, UK *For correspondence: [email protected], tel. +44 1224 272669 Woodward, S. 2017. Introduction Part 3: Other Invasive Tree Pathogens. Baltic Forestry 23(1): 253-254. The outbreak of ash dieback, caused by the spread ments of elm logs from North America. A previous epi- of Hymenoscyphus fraxineus in Europe has caused much demic of elm wilt, caused by Ophiostoma ulmi, had swept excitement in the public and press, rightly so, as yet anoth- through Europe in the early-mid 20th Century, but many er invasive pathogen spreads across the continent threaten- trees either recovered from the infection, or proved of low ing the stability of one of our iconic trees and the forest susceptibility. The appearance of a second pathogen caus- ecosystems it inhabits, from Russia to Northern Spain, ing Dutch elm disease, however, led to the deaths of mil- from Greece to Finland. As interest focuses to a great ex- lions of elms, and threatens the genus with extinction in tent on this particular problem, however, we must not lose Europe. The disease is still spreading in the northern-most sight of the many other invasive pathogens that are current- areas of Europe. Pecori et al. (2017), however, highlight ly spreading in Europe (Santini et al.