PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 3 Issue Iv || May 2021 ||

PIF – A++ ISSN 2581-6349 VOLUME 3 ISSUE IV || MAY 2021 || Email: [email protected] Website: www.jurisperitus.co.in 1 PIF – A++ ISSN 2581-6349 DISCLAIMER No part of this publication may be reproduced or copied in any form by any means without prior written permission of Editor-in-chief of Jurisperitus – The Law Journal. The Editorial Team of Jurisperitus holds the copyright to all articles contributed to this publication. The views expressed in this publication are purely personal opinions of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Editorial Team of Jurisperitus or Legal Education Awareness Foundation. Though all efforts are made to ensure the accuracy and correctness of the information published, Jurisperitus shall not be responsible for any errors caused due to oversight or otherwise. 2 PIF – A++ ISSN 2581-6349 EDITORIAL TEAM Editor-in-Chief ADV. SIDDHARTH DHAWAN Core-Team Member || Legal Education Awareness Foundation Phone Number + 91 9013078358 Email ID – [email protected] Additional Editor -in-Chief ADV. SOORAJ DEWAN Founder || Legal Education Awareness Foundation Phone Number + 91 9868629764 Email ID – [email protected] Editor MR. RAM AVTAR Senior General Manager || NEGD Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology Phone Number +91 9968285623 Email ID: [email protected] SMT. BHARTHI KUKKAL Principal || Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan, New Delhi Ministry of Human Resource and Development Phone Number + 91 9990822920 Email ID: [email protected] MS. NIKHITA Assistant Manager || Deloitte India Phone Number +91 9654440728 Email ID: [email protected] MR. TAPAS BHARDWAJ Member || Raindrops Foundation Phone + 91 9958313047 Email ID: [email protected] 3 PIF – A++ ISSN 2581-6349 ABOUT US Jurisperitus: The Law Journal is a non-annual journal incepted with an aim to provide a platform to the masses of our country and re-iterate the importance and multi-disciplinary approach of law. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

Ninth Series, Vol. X No, 23 Thursday, Oct,4,1990 Asvina12, 1990/1912(Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Third Session (Ninth Lok Sabha) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price: Rs., 50,00 C ONTENTS [Ninth Series, Vol. X, Third Session -Second Part, 199011912 iSaka)] No. 23, Thursday, October 4 ,1990/Asvina 12,1912 (Saka) Co l u mn s Re. Adjournment Motion 3—7 Police atrocities in dealing with students’ agitation against Government’s decision on Mandal Commission Report and resort to self-immolation by students against the decision Papers Laid on the Table 8—9 Motion Under Rule 388— Adopted 10 Suspension of Rule 338 Shri Mufti Mohammad Sayeed 10 Constitution (Seventy-sixth Amendment) Bill (Amendment of Article 356) -Introduced 10—11 Shri Mufti Mohammad Sayeed 10-11 Motion to consider 11-23 Shri Mufti Mohammad Sayeed 11 Clauses 2 and 1 23—39 Motion to Pass 39-59 Shri Mufti Mohammad Sayeed 39, 4 5 -4 6 Shri A. K. Roy 39—40 Dr. Thambi Durai 40—42 Shrimati Bimal Kaur Khalsa 42—44 Shri Inder Jit 4 4 -4 5 Re. Killing of innocent persons and burning of houses at Handwara in Jammu & Kashmir on 1st October, 1990 61—65 Re. Attention and care given by the Indian High Commission in London to Late Cuef Justice of India Shri Sabyasachi Mukherjee during his iltaess 65—111 Re. Setting up of Development Boards for Vidarbha, Marath- wada and other regions in Maharashtra. H I—116 (0 1 ^ 1 18S/N1>/91 (ii) Co l u m n s Adjournment Motion 117—206 Police atrocities in dealing with students’ dotation against Government’s decision on Mandal Commission Report and resort to self-immolation by students against the decision Shri B. -

ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY 32141-Contemporary India Since

ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY [ACCREDITED WITH ‘A+’ Grade by NAAC (CGPA:3.64) in the Third Cycle and Graded as Catego-rIy University by MHRD-UGC] (A State University Established by the Government of Tamiln adu) KARAIKUDI – 630 003 DIRECTORATE OF DISTANCE EDUCATION M.A HISTORY IV SEMESTER 32141-Contemporary India Since 1947 A.D Copy Right Reserved For Private use only INTRODUCTION India‘s independence represented for its people the start of an epoch that was imbued with a new vision. In 1947, the country commenced its long march to overcome the colonial legacy of economic underdevelopment, gross poverty, near-total illiteracy, wide prevalence of diseases, and stark social inequality and injustice. Achieving independence was only the first stop, the first break—the end of colonial political control: centuries of backwardness was now to be overcome, the promises of the freedom struggle to be fulfilled, and people‘s hopes to be met. The task of nation-building was taken up by the people and leaders with a certain elan and determination and with confidence in their capacity to succeed. When Nehru assumed office as the first Prime Minister of India, there were a myriad of issues lying in front of him, vying for his attention. Nehru knew that it was highly important that he prioritized things. For him, ―First things must come first and the first thing is the security and stability of India.‖ In the words of eminent political scientist W.H Morris- Jones, the imminent task was to ―hold things together, to ensure survival, to get accustomed to the feel of being in the water, to see to it that the vessels keep afloat‖. -

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools ICELAND 001041 Haskoli

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools ICELAND 001041 Haskoli Islands 046908 Icelandic Col Social Pedagogy 001042 Kennarahaskoli Islands 002521 Taekniskoli Islands 002521 Technical College Iceland 001042 Univ Col Education Iceland 001041 Univ Iceland INDIA 000702 A Loyola Col 000678 Abhyuday Skt Col 000705 Ac Col 000705 Ac Col Commerce 000705 Ac Training Col 000629 Academy Of Architecture 000651 Acharatlal Girdharlal Teachers 000705 Acharya Brajendra Nath Seal Co 000701 Acharya Thulasi Na Col Commerc 000715 Adarsh Degree Col 000707 Adarsh Hindi Col 000715 Adarsh Vidya Mandir Shikshak 000710 Adarsha Col Ed 000698 Adarsha Ed Societys Arts Sci C 000710 Adhyapak Col 000701 Adichunchanagiri Col Ed 000701 Adichunchanagiri Inst Tech 000678 Adinath Madhusudan Parashamani 000651 Adivasi Arts Commerce Col Bhil 000651 Adivasi Arts Commerce Col Sant 000732 Adoni Arts Sci Col 000710 Ae Societys Col Ed 000715 Agarwal Col 000715 Agarwal Evening Col 000603 Agra University 000647 Agrasen Balika Col 000647 Agrasen Mahila Col 000734 Agri Col Research Inst Coimbat 000734 Agri Col Research Inst Killiku 000734 Agri Col Research Inst Madurai 000710 Agro Industries Foundation 000651 Ahmedabad Arts Commerce Col 000651 Ahmedabad Sci Col 000651 Ahmedabad Textile Industries R 000710 Ahmednagar Col 000706 Aizwal Col 000726 Aja Col 000698 Ajantha Ed Societys Arts Comme 000726 Ajra Col 000724 Ak Doshi Mahila Arts Commerce 000712 Akal Degree Col International Schools 000712 Akal Degree Col Women 000678 Akhil Bhartiya Hindi Skt Vidya 000611 Alagappa College Tech, Guindy 002385 -

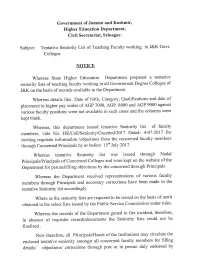

Tentative Seniority List of Teaching Faculty Working in Jammu and Kashmir Government Colleges. As on 1-07-2017

Tentative Seniority list of Teaching faculty working in Jammu and Kashmir Government Colleges. As on 1-07-2017. Date of placement Date of Present place of S.No Name Category Qualification Subject DOB appointment AGP 7000/- ABP 8000/- AGP 9000/- posting 1 Nighat Wani Home Sc. 15.Mar.1959 18.Aug.1980 2 Sohan Lal SC M.Sc. Geography 14.Sep.1957 4.Mar.1983 Retired 3 Nirmal Narayan M.Sc/B.Ed Geography 10.Jun.1961 4.Mar.1983 GDC Kathua 4 Shagufta Yasvi Ph.D Chemistry 21.Mar.1959 14.Mar.1983 5 Sudha Gupta Open M. Sc Home.Sc 23.Mar.1958 29.Jun.1983 01.01.2006 WC Gandhinagar 6 Yudvir Singh Ph. D Commerce 20.Apr.1958 15.Jul.1983 RUSA 7 Zahir-Ud-Din M.Com Commerce 18.Oct.1958 16.Jul.1983 8 Neeru Balla Open M.Com Commerce 15.Oct.1960 16.Jul.1983 01.01.1996 27.07.1998 01.01.2006 SPMR College 9 Bushra Shamin M.Com Commerce 21.Mar.1959 16.Jul.1983 10 Kiran Kumari Open M.Com Commerce 1.May.1960 16.Jul.1983 01.01.1996 27.07.1998 01.01.2006 SPMR College 11 Suman Bala M.Com Commerce 17.Mar.1959 16.Jul.1983 12 Rakesh Gupta Open Ph. D Commerce 16.Nov.1958 16.Jul.1983 01.08.1991 01.08.1996 01.01.2006 MAM College 13 Ab. Roaf M. Phil Commerce 8.Jan.1961 16.Jul.1983 claim for Sr. 2 14 Rifat Geelani M.A. Arabic 8.Apr.1960 29.Sep.1983 15 Abdul Hai Ph.d. -

The Revolt of 1857

1A THE REVOLT OF 1857 1. Objectives: After going through this unit the student wilt be able:- a) To understand the background of the Revolt 1857. b) To explain the risings of Hill Tribes. c) To understand the causes of The Revolt of 1857. d) To understand the out Break and spread of the Revolt of 1857. e) To explain the causes of the failure of the Revolt of 1857. 2. Introduction: The East India Company's rule from 1757 to 1857 had generated a lot of discontent among the different sections of the Indian people against the British. The end of the Mughal rule gave a psychological blow to the Muslims many of whom had enjoyed position and patronage under the Mughal and other provincial Muslim rulers. The commercial policy of the company brought ruin to the artisans and craftsman, while the divergent land revenue policy adopted by the Company in different regions, especially the permanent settlement in the North and the Ryotwari settlement in the south put the peasants on the road of impoverishment and misery. 3. Background: The Revolt of 1857 was a major upheaval against the British Rule in which the disgruntled princes, to disconnected sepoys and disillusioned elements participated. However, it is important to note that right from the inception of the East India Company there had been resistance from divergent section in different parts of the sub continent. This resistance offered by different tribal groups, peasant and religious factions remained localized and ill organized. In certain cases the British could putdown these uprisings easily, in other cases the struggle was prolonged resulting in heavy causalities. -

2020-2021 (As on 31 July, 2020)

NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL (NAAC) Universities accredited by NAAC having valid accreditations during the period 01.07.2020 to 30.06.2021 ACCREDITATION VALID S. NO. STATE NAME UPTO 1 Andhra Pradesh Acharya Nagarjuna University, Guntur – 522510 (Third Cycle) 12/15/2021 2 Andhra Pradesh Andhra University,Visakhapatnam–530003 (Third Cycle) 2/18/2023 Gandhi Institute of Technology and Management [GITAM] (Deemed-to-be-University u/s 3 of the UGC Act 1956), 3 Andhra Pradesh 3/27/2022 Rushikonda, Visakhapatnam – 530045 (Second Cycle) 4 Andhra Pradesh Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University Kakinada, East Godavari, Kakinada – 533003 (First Cycle) 5/1/2022 Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha (Deemed-to-be-University u/s 3 of the UGC Act 1956), Tirupati – 517507 (Second 5 Andhra Pradesh 11/14/2020 Cycle) 6 Andhra Pradesh Sri Krishnadevaraya University Anantapur – 515003 (Third Cycle) 5/24/2021 7 Andhra Pradesh Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam, Tirupati – 517502 (Third Cycle) 9/15/2021 8 Andhra Pradesh Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati, Chittoor - 517502 (Third Cycle) 6/8/2022 9 Andhra Pradesh Vignan's Foundation for Science Technology and Research Vadlamudi (First Cycle) 11/15/2020 10 Andhra Pradesh Yogi Vemana University Kadapa (Cuddapah) – 516003 (First Cycle) 1/18/2021 11 Andhra Pradesh Dravidian University ,Srinivasavanam, Kuppam,Chittoor - 517426 (First Cycle) 9/25/2023 Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation (Deemed-to-be-University u/s 3 of the UGC Act 1956),Green Fields, 12 Andhra Pradesh 11/1/2023 Vaddeswaram,Guntur -

The Role of 1Reasonable Restrictions* in the Indian Constitution Tirukkattupalli Kalyana Krishnamurthy Iyer June, 1974

THE ROLE OF 1 REASONABLE RESTRICTIONS* IN THE INDIAN CONSTITUTION TIRUKKATTUPALLI KALYANA KRISHNAMURTHY IYER JUNE, 1974 ProQuest Number: 11010392 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010392 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 x. CONTENTS Page No. Acknowledgements i. Preface ii. List of Abbreviations viii. INTRODUCTION: THE NATURE OF THE SUBJECT-MATTER GENERALLY 1. •Subjectivity* and •Objectivity* in Reas onableness 1 0 . An Introduction to Article 19 CHAPTER 1: HISTORY AND COMPARISONS Section Is The Indian Constituent Assembly and Limitation of Rights 17. Proceedings of the Advisory Committee 20. Assembly Proceedings - Stage 1 3 2 . Assembly Proceedings - Stage 2 39. Section 2 : »Due Process1 in American Law and •Reasonableness* in India 44. Indian Constituent Assembly and •Due Process* : In Outline 45. The *Ghost* of * Due Process* 49. Vagueness and Unreasonableness 68. Section 3 : The Role of Reasonableness in English Law 76. English Law on * Reasonableness* 83. Liversidge v# Anderson 87. Bye-laws and Indian Courts 1 0 2 . Section 4: The European Convention Introduction 106. -

Tentative Seniority List of Teaching Faculty Working in J&K Govt

Tentative Seniority list of Teaching faculty working in Jammu and Kashmir Government Colleges. As on 1-07-2017. Date of placement Date of Present place of S.No Name Category Qualification Subject DOB appointment AGP 7000/- ABP 8000/- AGP 9000/- posting 1 Nighat Wani Home Sc. 15.Mar.1959 18.Aug.1980 2 Nirmal Narayan M.Sc/B.Ed Geography 10.Jun.1961 4.Mar.1983 GDC Kathua 3 Shagufta Yasvi Ph.D Chemistry 21.Mar.1959 14.Mar.1983 4 Sudha Gupta Open M. Sc Home.Sc 23.Mar.1958 29.Jun.1983 01.01.2006 WC Gandhinagar 5 Yudvir Singh Ph. D Commerce 20.Apr.1958 15.Jul.1983 RUSA 6 Zahir-Ud-Din M.Com Commerce 18.Oct.1958 16.Jul.1983 7 Neeru Balla Open M.Com Commerce 15.Oct.1960 16.Jul.1983 01.01.1996 27.07.1998 01.01.2006 SPMR College 8 Bushra Shamin M.Com Commerce 21.Mar.1959 16.Jul.1983 9 Kiran Kumari Open M.Com Commerce 1.May.1960 16.Jul.1983 01.01.1996 27.07.1998 01.01.2006 SPMR College 10 Suman Bala M.Com Commerce 17.Mar.1959 16.Jul.1983 11 Rakesh Gupta Open Ph. D Commerce 16.Nov.1958 16.Jul.1983 01.08.1991 01.08.1996 01.01.2006 MAM College 12 Ab. Roaf M. Phil Commerce 8.Jan.1961 16.Jul.1983 claim for Sr. 2 13 Rifat Geelani M.A. Arabic 8.Apr.1960 29.Sep.1983 14 Abdul Hai Ph.d. Zoology 13.Oct.1961 16.Jun.1984 26-Jun-1992 27-Jul-1998 1-Jan-2006 Amar Singh College 15 Nasreen Malik M.Phil Zoology 26.Mar.1958 16.Jun.1984 16 Kartar Chand SC M.Sc. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXIV NO.4 DECEMBER 2018 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.4 DECEMBER 2018 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ The Journal of Parliamentary Information _____________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.4 DECEMBER 2018 CONTENTS Page EDITORIAL NOTE ... ADDRESS - Address by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Smt. Sumitra Mahajan at the function to confer Outstanding Parliamentarian Awards … PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES … PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL … DEVELOPMENTS PRIVILEGE ISSUES … PROCEDURAL MATTERS … DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND … PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha … Rajya Sabha … State Legislatures … RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST … APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the … Fifteenth Session of the Sixteenth Lok Sabha II. Statement showing the work transacted during the … 246th Session of the Rajya Sabha III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of … the States and Union Territories during the period 1 July to 30 September 2018 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament … and assented to by the President during the period 1 July to 30 September 2018 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States … and the Union Territories during the period 1 July to 30 September 2018 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union … and State Governments during the period 1 July to 30 September 2018 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, the Rajya Sabha … and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories INDEX … ADDRESS AT THE FUNCTION TO CONFER OUTSTANDING PARLIAMENTARIAN AWARDS FOR THE YEARS 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 AND 2017 AT THE CENTRAL HALL OF PARLIAMENT HOUSE, NEW DELHI _____________________________________________________________________________ On 1 August 2018, Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha, Smt. -

![Rethinking State Politics in India Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Rethinking State Politics in India](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4370/rethinking-state-politics-in-india-downloaded-by-university-of-defence-at-01-31-24-may-2016-rethinking-state-politics-in-india-4024370.webp)

Rethinking State Politics in India Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Rethinking State Politics in India

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Rethinking State Politics in India Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 Rethinking State Politics in India Regions within Regions Editor Ashutosh Kumar Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI First published 2011 in India by Routledge 912–915 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2011 Ashutosh Kumar Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Limited D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, Noida 201 301 Printed and bound in India by Baba Barkha Nath Printers MIE-37, Bahadurgarh, Haryana 124507 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:31 24 May 2016 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-59777-7 This book is printed on ECF environment-friendly paper manufactured from unconventional and other raw materials sourced from sustainable and identified sources. Contents List of Tables and Charts ix Preface and Acknowledgements xiii Introduction — Rethinking State Politics in India: Regions within Regions 1 Ashutosh Kumar Part I: United Colours of New States 1. -

January 2018 Edition

IASBUZZ JANUARY 2018 EDITION BrainyIAS (84594-00000) Preface Even after all this time the Sun never tells the earth, “You owe me”. Look what happens with a love like that. It lights the whole sky. ~Hafiz We humans are rational beings. We need logics to understand the phenomena happening around us. This inquisitive nature of humans has led to various discoveries, inventions and other scientific advances. Despite all this, there are still some questions which remain unanswered and have remained so since the beginning of the time. The questions like- How and why time came into being? How and why the universe came into being? What is the purpose of human life on this earth? And the biggest puzzle that boggles our minds is on death and after-death phenomena. Ajit Singh, DIG (Retd) Similarly, we need answers to the social phenomena happening around us. The most disturbing question is that despite possessing a rational mind, why many amongst us wish to be the slaves of illegitimate fantasies? The purpose might be to satisfy the queries that I have mentioned above. I am talking about the blind faith that millions of Indians have invested in various religious institutions, sects, deras et al. I call faith an “investment”, because faith is something which is expected to yield manifolds. As a rational being, I would like to invest my time, my intellect, my energy and my trust somewhere I can get a return from. That return may be in the form of answers to the above mentioned questions or simply a feeling of peace and solace and ultimately make me more humane.