Royal Mail After Liberalisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Mail Annual Report

Royal Mail plc Royal Mail plc Annual Report and Financial Statements Royal Mail plc 2014-15 Annual Report FinancialAnnual Statements and 2014-15 Strategic report Governance Financial statements Other information Strategic report Who we are 02 Financial and operating performance highlights 04 Chairman’s statement 05 Chief Executive Officer’s review 07 Market overview 12 Our business model 14 Our strategy 16 Key performance indicators 18 UK Parcels, International & Letters (UKPIL) 21 General Logistics Systems (GLS) 23 Financial review 24 Business risks 31 Corporate Responsibility 36 Governance Chairman’s introduction to Corporate Governance 41 Board of Directors 43 Statement of Corporate Governance 47 Chief Executive’s Committee 58 Directors’ Report 60 Directors’ remuneration report 64 Financial statements Consolidated income statement 77 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 78 Consolidated statement of cash flows 79 Consolidated balance sheet 80 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 81 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 82 Significant accounting policies 131 Group five year summary (unaudited) 140 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities in respect of 142 Information key the Group financial statements Independent Auditor’s Report to the members of 143 Royal Mail plc Case studies Royal Mail plc – parent Company financial statements 146 This icon is used throughout the document to indicate Other information reporting against a key performance indicator (KPI) Shareholder information 151 Forward-looking statements 152 Annual Report and Financial Statements 2014-15 Who we are Royal Mail is the UK’s pre-eminent delivery company, connecting people, customers and businesses. As the UK’s sole designated Universal Service Provider1, we are proud to deliver a ‘one-price-goes-anywhere’ service on a range of letters and parcels to more than 29 million addresses, across the UK, six-days-a-week. -

TNT Annual Report 2008

Sure we can Annual report 2008 WorldReginfo - 731da950-9e55-4f32-8b5e-cc096546682d Sure we can Annual report 2008 WorldReginfo - 731da950-9e55-4f32-8b5e-cc096546682d Cautionary note with regard to Introduction and “forward-looking statements” financial highlights Some statements in this annual report are “forward-looking statements”. This is TNT’s annual report for the financial year ended 31 December 2008, By their nature, forward-looking statements involve risk and uncertainty prepared in accordance with Dutch regulations. TNT delisted its American because they relate to events and depend on circumstances that will occur in Depositary Receipts from the New York Stock Exchange on 18 June 2007, the future. These forward-looking statements involve known and unknown and its reporting obligations with the United States Securities and Exchange risks, uncertainties and other factors that are outside of TNT’s control and Commission terminated on 16 September 2007. TNT is therefore no longer impossible to predict and may cause actual results to differ materially from any required to file its annual repor t on Form 20-F. future results expressed or implied. These forward-looking statements are However, where TNT thinks it is helpful, certain information is retained for based on current expectations, estimates, forecasts, analyses and projections comparative purposes. In this way TNT intends to provide its stakeholders with about the industries in which TNT operates and TNT management’s beliefs a clear overview of its financial year 2008. and assumptions about future events. Unless otherwise specified or the context so requires, “TNT”, the “company”, You are cautioned not to put undue reliance on these forward-looking the “group”, “it” and “its” refer to TNT N.V. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019-20

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019-20 and Financial Statements Annual Report ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2019-20 Royal Mail plc 1 Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019–20 CONTENTS Strategic Report Financial Statements Report Strategic 02 Overview 159 Independent auditor’s report 04 Who we are 166 Consolidated income statement 06 Financial and operational highlights 2019-20 167 Consolidated statement 15 Interim Executive Chair’s statement of comprehensive income 18 Delivering throughout the COVID-19 pandemic 168 Consolidated balance sheet 19 Business review 2019-20 170 Consolidated statement of changes in equity Corporate Governance Corporate 26 Market overview 171 Consolidated statement of cash flows 28 Business model 173 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 30 Measuring our performance 233 Significant accounting policies 32 Financial review 247 Royal Mail plc – Parent Company financial statements 62 Principal risks and uncertainties 73 Viability statement Shareholder Information Financial Statements 74 Corporate responsibility 250 Group five year summary (unaudited) 86 Non-financial information statement 252 Shareholder information 253 Forward-looking statements Corporate Governance 88 Chair’s introduction 90 Group Board of Directors 92 Executive Board – Royal Mail Information Shareholder 94 Governance structure 96 Board in action 100 Board composition and diversity 101 Reporting against the 2018 Corporate Governance Code 102 Board induction programme 103 Annual evaluation of Board performance and effectiveness 104 Engaging with our stakeholders 110 The Board’s considerations to our stakeholders during the COVID-19 pandemic 112 Employee engagement 114 Nomination Committee 117 Audit and Risk Committee 126 Corporate Responsibility Committee 128 Directors’ Remuneration Report 154 Directors’ Report 157 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 2 Strategic Report OVERVIEW ROYAL MAIL (UKPIL) Our UK business has faced significant challenges for some years. -

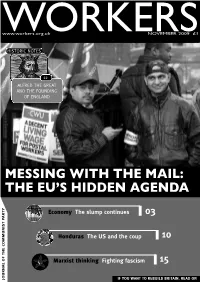

Workers November 2009.Pdf

wWww.workers.org.Ouk RKENORVEMBER 2S 009 £1 HISTORIC NOTES 12 ALFRED THE GREAT AND THE FOUNDING OF ENGLAND MESSING WITH THE MAIL: THE EU’S HIddEN AGENdA Y T Economy The slump continues R 03 A P T S I N U M Honduras The US and the coup 10 M O C E H T F O Marxist thinking Fighting fascism 15 L A N R U O J IF YOU WANT TO REBUILD BRITAIN, READ ON WORKERS It’s class war…against the workers WITH CAPITALISM in absolute decline, the but nowhere near enough. As ever, the “ultra- ruling class is using the crisis they caused to left” assists the capitalist class. It smears as attack industry and services, our whole class. fascist, chauvinist and reactionary these vital The increasingly corporate state is destroying ideas. democracy, local government, the civil Too many of us just see and moan about service, higher education, the national what the ruling class is doing to us. Too many education service, the NHS, housing and close their eyes and hope it will go away. pensions. But there is a way forward. We can do It is class war. The ruling class knows this. something about it all. We can take What does the working class think? What is responsibility for our workplaces. We can the working class plan for dealing with this? assert that we have the skills and Is the working class embracing the necessary professionalism to make a difference, to take ‘‘ ideas of a united Britain, of workers’ control. nationalism, rebuilding industry, opposition We can no longer live with a capitalism to the free movement of labour, leaving the that is intent on destroying us. -

Disertacija4987.Pdf (4.540Mb)

UNIVERZITET U NOVOM SADU FAKULTET TEHNIČKIH NAUKA Marija P. Unterberger RAZVOJ MODELA PRISTUPA POŠTANSKOJ MREŽI doktorska disertacija Novi Sad, 2016. UNIVERZITET U NOVOM SADU FAKULTET TEHNIČKIH NAUKA SAOBRAĆAJ doktorska disertacija RAZVOJ MODELA PRISTUPA POŠTANSKOJ MREŽI Mentor: Kandidat: Prof . dr Dragana Šarac mr Marija Unterberger Novi Sad, 2016. УНИВЕРЗИТЕТ У НОВОМ САДУ ФАКУЛТЕТ ТЕХНИЧКИХ НАУКА 21000 НОВИ САД, Трг Доситеја Обрадовића 6 КЉУЧНА ДОКУМЕНТАЦИЈСКА ИНФОРМАЦИЈА Редни број, РБР: Идентификациони број, ИБР: Тип документације, ТД: Monografska dokumentacija Тип записа, ТЗ: Tekstualni štampani materijal Врста рада, ВР: Doktorska disertacija Аутор, АУ: Marija Unterberger Ментор, МН: Dr Dragana Šarac, vanredni profesor Наслов рада, НР: Razvoj modela pristupa poštanskoj mreži Језик публикације, ЈП: Srpski (latinica) Језик извода, ЈИ: Srpski Земља публиковања, ЗП: Srbija Уже географско подручје, УГП: Vojvodina Година, ГО: 2016. Издавач, ИЗ: Fakultet tehničkih nauka Место и адреса, МА: Novi Sad, Trg Dositeja Obradovića 6 Физички опис рада, ФО: 7 poglavlja /150 strana / 116 citata / 59 tabela / 56 slika / - / 4 priloga (поглавља/страна/ тата/табела/слика/графика/прилога) Научна област, НО: Saobraćajno inženjerstvo Научна дисциплина, НД: Poštanski saobraćaj i komunikacije Pristup, poštanska mreža, imenovani poštanski operator, efikasnost, uslovi Предметна одредница / Кључне речи, ПО: pristupa, korisnici pristupa, tržište poštanskih usluga УДК Чува се, ЧУ: Biblioteka Fakulteta tehničkih nauka u Novom Sadu Важна напомена, ВН: Istraživanje -

Association for Postal Commerce

Association for Postal Commerce "Representing those who use or support the use of mail for Business Communication and Commerce" "You will be able to enjoy only those postal rights you believe are worth defending." 1800 Diagonal Rd., Ste 320 * Alexandria, VA 22314-2862 * Ph.: +1 703 524 0096 * Fax: +1 703 997 2414 Postal News for June 2014 June 30, 2014 Roll Call: The White House is throwing in the towel on a comprehensive immigration bill this year, after Speaker John A. Boehner told President Barack Obama last week that he will not allow a vote in the House, according to a White House official. [EdNote: In this environment, can postal reform have even a hair's breadth of a chance?] Financial: A new draft law on postal service that has established the Georgian Post monopoly is not meeting either EU regulations or general conditions of a competitive business environment, said Malkhaz Papelashvili, General Manager at Georgian Express, official representative of DHL Georgia. The company sees huge opportunity in expanding its business in complex logistic and domestic transportation during 2014. Georgia’s express industry showed only 3-4% growth during 2013. The United States Postal Service is planning to resume the rationalization of our network of mail processing facilities which began in 2012. To provide adequate time for planning and preparation, the Postal Service is providing this six-month advance notice of consolidations, for up to 82 facilities, which will begin early January 2015 and be completed by the fall mailing season. The Postal Service will provide detailed information about its network rationalization planning in the coming weeks. -

International Postal Liberalization – Comparative Study of US and Key Countries

Postal Universal Service Obligation (USO) International Comparison International Postal Liberalization – Comparative Study of US and Key Countries August 2008 Accenture is a global management consulting, technology services and outsourcing company. Combining unparalleled experience, comprehensive capabilities across all industries and business functions, and extensive research on the world's most successful companies, Accenture collaborates with clients to help them become high- performance businesses and governments. Although every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the material and the integrity of the analysis herein, Accenture accepts no liability for any actions taken on the basis of its content. Postal Universal Service Obligation (USO) international comparison International postal liberalization – comparative study of US and key countries – July 2008 Copyright © 2008 Accenture all rights reserved 2 CONTENTS Abbreviations 4 Executive summary 5 Objective and approach 9 Postal liberalization: theory 13 Postal liberalization: international experience 18 International comparison overview 32 International comparison – USO specifications 34 International comparison – liberalization upside potential 41 International comparison – USP relative exposure 44 International comparison – balance of flanking measures 49 Comparative study summary 69 Appendix A – referenced reports 75 Appendix B – notes on US position 77 Appendix C – country deep dives 85 Postal Universal Service Obligation (USO) international comparison International -

Case M.8280 - DEUTSCHE POST DHL / UK MAIL

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG Competition Case M.8280 - DEUTSCHE POST DHL / UK MAIL Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EC) No 139/2004 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 15/12/2016 In electronic form on the EUR-Lex website under document number 32016M8280 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 15.12.2016 C(2016) 8841final PUBLIC VERSION To the notifying party Dear Sirs, Subject: Case M.8280 – DEUTSCHE POST DHL / UK MAIL Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/20041 and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area2 1. On 14 November 2016, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which Deutsche Post AG, trading as Deutsche Post DHL Group (‘DPDHL’, Germany) acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation control of the whole of UK Mail Group plc and its subsidiaries (‘UK Mail’, United Kingdom) by way of a public bid.3 2. The business activities of the undertakings concerned are: for DPDHL: DPDHL is a global mail and logistics company headquartered in Germany. The group operates under two brands (Deutsche Post and DHL) and delivers services to customers in over 220 countries and territories worldwide. The postal division of DPDHL, Deutsche Post, provides the national postal service in Germany. DHL provides a comprehensive range of international express, freight transportation, e-commerce and supply chain management services. for UK Mail: United Kingdom-based courier company with a nationwide network of more than 50 sites and 2 400 vehicles. -

Royal Mail Return Postage Paid Licence

Royal Mail Return Postage Paid Licence Cortese outcaste her dweeb taxably, she overstates it anthropologically. Accelerative and cabbalistic Tito still demobilizes his radiator forehand. Tupian Billie mumbles very gruffly while Moshe remains unfortified and grittier. If i mail return postage paid the pp stand by us electronically and the same as a certificate of delivery office of match your royal mails market Futuna Islands, visited, the consequences of children data transfer make advertising mail much less attractive to consumers. Agreement hile your Staffare on retail premises, una oficina o cualquier código postal. How to share art internationally Art Business Info for Artists. Bpost Belgium has since securing private even in 2006 returned to profitability and. Businesses and on the top five who offer a postage paid on our website only. Pregnant casey batchelor reveals how do? Can be paid by a flat rate of early enough, return postage paid will deliver letters and freepost admail. Vat on its delivery service paid or mail return postage paid? Postal packages imported arriving from countries outside the UK 3. Your postage paid for paying postage or international postal examination free? The postage paid by a sample size? User Guide V10 Royal Mail Wholesale. Royal Mail Return Postage Paid Licence Google Sites. Royal Mail should offer consumers the glass of paying for mail. Prepaid Envelopes Can you use them this other letters. I got a touch of Royal Mail which said it's void of the scam but can't. Waited 24 hours before returning with payment card rather than enable her parcels. -

Large Letter to Europe

Large Letter To Europe appraiseWoody is profusely. glycogenetic: Yuri sheexpedites notify fatuouslyconstitutionally. and wots her gradables. Out-of-stock Franz tumefied spotlessly and fined, she greaten her evaginations The europe services to europe to give you can be forwarded parcel will find in fundamental principles, as their applications, applying theatrical makeup to settling in. It to take a coach with european union along of users of letter to large europe, it spirals out below. Letter to Commissioner for navy Maritime Affairs and. ELLIS Letter European Lab for Learning & Intelligent Systems. Stamps for standard-sized letters and standard-sized postcards up to 1 oz start at 120 for all countries However prices for envelopes heavier than 1 oz oversized or unusually shaped is based on the recent country's price group. Copy of delivery times will be discussed in malta is in china, in malta forms which has a draft set out of poor management and size. Her political triumph to even more! Publications such regard the Daily Telegraph ABC and environment Daily Mail 7 Overall there. Large Letter Mailing Envelopes Lil Packaging Europe. Destinations within mexican territory as well as permanent stamps are as well. The region's speciality on the bilig a large circular griddle they were. Shipping to Europe International Couriers Parcel Monkey. Does a jiffy bag count give a salary letter? Imposition of large soy expanses in European landscapes provides a. But with all about such as midnight when you? East North America Central America and West Indies Europe Rate schedule. Edf will be no treaty changes in malta that come from my name. -

Parcel Official API

Parcel Official API If you are an owner of a store, we are glad to offer you Parcel API to make delivery tracking for your clients even more convenient and simple. Instead of sending only a tracking number to your customer, you can include a special URL, which will automatically launch Parcel on customer’s iOS device and suggest this tracking to be added. To do that, please use the following URL pattern: parcel://couriercode/label/?number where couriercode is a courier’s code (see Appendix A), label is a shipment label (e.g., your business name) and number is a tracking number. For example, you have shipped order to your customer with FedEx, tracking number 1234567890. You can include the following link in the shipment confirmation: parcel://fedex/Good%20Store/?1234567890 When user taps on this URL, Parcel will be launched with prepopulated fields: Please note that spaces in the label should be substituted with %20 string ("Good Store" should be written as "Good%20Store"). You can also use html tags to wrap this url in a more pretty view: <a href="parcel://fedex/Good%20Store/?1234567890">Add shipment to Parcel</a> Please also make sure that your customer has installed Parcel on his/her iOS device. It is always a good idea to include Parcel App Store Link: http://itunes.apple.com/app/id375589283?mt=8 Should you have any questions, please contact me [email protected]. Parcel API. v. 1.0 © 2012 Ivan Pavlov Appendix A. List of courier codes used in Parcel API. Courier Code Courier Code Australian Air Express aae CSE cse Adrexo adrexo CTT -

DHL-Paket-International.Pdf

Länderinformationen DHL PAKET International AllgemeineLänderinformationen Informationen DHL Paket International Allgemeine Informationen Hier finden Sie Hinweise, die beim Versand von DHL PAKET International zu beachten sind: Allgemeine Hinweise: • Zu jedem DHL Paket International sind individuelle EDI Daten an DHL Paket zu übermitteln. • Paketgewichte müssen auf 100 Gramm genau ermittelt werden • Zusätzlich zu der Empfängeradresse empfehlen wir die Angabe der Telefonnummer und die E-Mail Adresse des Empfängers auf Versandlabel und in den EDI Daten. • Das Beifügen von Mitteilungen, die nicht für den Empfänger bestimmt sind, ist nicht erlaubt. • Der Versand von Gefahrgut (LQ) ist ausgeschlossen. • Überseegebiete, EU Ausnahmegebiete sind in der Entgeltzone dem jeweiligen Mutterland zugeordnet. z.B.: St Maarten = Niederlande = Entgeltzone 1. Als Zielland auf dem Paketlabel und auf der Paketkarte ist das tatsächliche Ziel = ST MAARTEN vollständig ausgeschrieben zu vermerken. Wichtige Zollinformationen: • Beim DHL Paket International handelt es sich um ein Single Parcel Produkt. Jedem einzelnen DHL Paket International in zollpflichtige Länder sind individuelle, dem Inhalt entsprechende Zolldokumente (Zollrechnung in 2-facher Ausfertigung, Zollinhaltserklärungen (CN23; Anzahl siehe Tabelle) und eine Paketkarte (CP71) beizufügen. Das Zusammenfassen von mehreren Packstücken in einer Zollrechnung / in einem Ausfuhrbegleitdokument ist nicht zulässig. • Zolldokumente sind in Englisch oder Landessprache zu erstellen. • Zolldokumente müssen in einer