1991 Investigations at Fort Gibraltar I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Selkirk Settlement and the Settlers. a Concise History of The

nus- C-0-i^JtJL^e^jC THE SELKIRK SETTLEMENT AND THE SETTLERS. ACONCISK HISTORY OF THE RED RIVER COUNTRY FROM ITS DISCOVEEY, Including Information Extracted from Original Documents Lately Discovered and Notes obtained from SELKIRK SETTLEMENT COLONISTS. By CHARLES N, BELL, F.R.G-.S., Honorary Corresponding Member of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, Hamilton Association, Chicago Academy ot Science, Buffalo Historical Society, Historian of Wolseley's Expeditionary Force Association, etc., etc. Author ot "Our Northern Waters," "Navigation of Hudson's Bay and Strait," "Some Historical Names and - Places ot Northwest Canada,' "Red River Settlement History,"" Mound-builders in Manitoba." "Prehistoric Remains in the Canadian Northwest," "With the Half-breed Buffalo Hunters," etc., etc. Winnipeg : PRINTED Vf THE OFFICE 01 "THE COMHERCIA] ," J klftES ST. BAST. issT. The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE COLLECTION of CANADIANA Queen's University at Kingston c (Purchased primj^arm Pkra Qplkctiaru at Quun's unwersii/ oKmc J GfakOurwtt 5^lira cImst- >• T« Selkirk Settlement and the Settlers." By CHARLES X. BELL, F.R.G.S. II [STORY OF II B Ti: IDE. Red River settlement, and stood at the north end of the Slough at what is now About 17.'><i LaN erandyre, a French-Can- Donald adian, established on the Red river a known as Fast Selkirk village. Mr. colonists, in- trading post, which was certainly the first Murray, one of the Selkirk of occasion that white men had a fixed abode forms me that he slept at the ruins in the lower Red River valley. After 1770 such a place in the fall of 1815, when the English merchants and traders of arriving in this country. -

S C H O O L Program

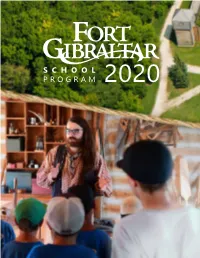

SCHOOL PROGRAM 2020 INTRODUCTION We invite you to learn about Fort Gibraltar’s influence over the cultural development of the Red River settlement. Delve into the lore of the French Canadian voyageurs who paddled across the country, transporting trade-goods and the unique customs of Lower Canada into the West. They married into the First Nations communities and precipitated the birth of the Métis nation, a unique culture that would have a lasting impact on the settlement. Learn how the First Nations helped to ensure the success of these traders by trapping the furs needed for the growing European marketplace. Discover how they shared their knowledge of the land and climate for the survival of their new guests. On the other end of the social scale, meet one of the upper-class managers of the trading post. Here you will get a glimpse of the social conventions of a rapidly changing industrialized Europe. Through hands-on demonstrations and authentic crafts, learn about the formation of this unique community nearly two hundred years ago. Costumed interpreters will guide your class back in time to the year 1815 to a time of immeasurable change in the Red River valley. 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Fort Gibraltar Admission 866, Saint-Joseph St. Guided Tour Managed by: Festival du Voyageur inc. School Groups – $5 per student Phone: 204.237.7692 Max. 80 students, 1.877.889.7692 Free admission for teachers Fax: 204.233.7576 www.fortgibraltar.com www.heho.ca Dates of operation for the School Program Reservations May 11 to June 26, 2019 Guided tours must be booked at least one week before your outing date. -

Vanguards of Canada

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY WiLLARD FiSKE Endowment """"""" '""'"'^ E 78.C2M162" Vanguards of Canada 3 1924 028 638 488 A Cornell University S Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028638488 VANGUARDS OF CANADA BOOKS The Rev. John Maclean, M.A., Ph.D., B.D. Vanguards of Canada By JOHN MACLEAN, M.A., Ph.D.. D.D. Member of the British Association, The American Society for the Advance- ment of Science, The American Folk-Lore Society, Correspondent of The Bureau of Ethnology, Washington; Chief Archivist of the Methodist Church, Canada. B 13 G TORONTO The Missionary Society of the Methodist Church The Young People's Forward Movement Department F. C. STEPHENSON, Secretary 15. OOPTRIGHT, OanADA, 1918, BT Frboeriok Clareb Stbfhekgon TOROHTO The Missionary Society of the Methodist Church The Young People's Forward Movement F. 0. Stephenson , Secretary. PREFACE In this admirable book the Rev. Dr. Maclean has done a piece of work of far-reaching significance. The Doctor is well fitted by training, experience, knowledge and sym- pathy to do this work and has done it in a manner which fully vindicates his claim to all these qualifications. Our beloved Canada is just emerging into a vigorous consciousness of nationhood and is showing herself worthy of the best ideals in her conception of what the hig'hest nationality really involves. It is therefore of the utmost importance that the young of this young nation thrilled with a new sense of power, and conscious of a new place in the activities of the world, should understand thoroughly those factors and forces which have so strikingly combined to give us our present place of prominence. -

Medicine in Manitoba

Medicine in Manitoba THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS /u; ROSS MITCHELL, M.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY LIBRARY FR OM THE ESTATE OF VR. E.P. SCARLETT Medic1'ne in M"nito/J" • THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS By ROSS MITCHELL, M. D. .· - ' TO MY WIFE Whose counsel, encouragement and patience have made this wor~ possible . .· A c.~nowledg ments THE LATE Dr. H. H. Chown, soon after coming to Winnipeg about 1880, began to collect material concerning the early doctors of Manitoba, and many years later read a communication on this subject before the Winnipeg Medical Society. This paper has never been published, but the typescript is preserved in the medical library of the University of Manitoba and this, together with his early notebook, were made avail able by him to the present writer, who gratefully acknowledges his indebtedness. The editors of "The Beaver": Mr. Robert Watson, Mr. Douglas Mackay and Mr. Clifford Wilson have procured informa tion from the archives of the Hudson's Bay Company in London. Dr. M. T. Macfarland, registrar of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba, kindly permitted perusal of the first Register of the College. Dr. J. L. Johnston, Provincial Librarian, has never failed to be helpful, has read the manuscript and made many valuable suggestions. Mr. William Douglas, an authority on the Selkirk Settlers and on Free' masonry has given precise information regarding Alexander Cuddie, John Schultz and on the numbers of Selkirk Settlers driven out from Red River. Sheriff Colin Inkster told of Dr. Turver. Personal communications have been received from many Red River pioneers such as Archbishop S. -

The Conquest of the Great Northwest Piled Criss-Cross Below Higher Than

The Conquest of the Great Northwest festooned by a mist-like moss that hung from tree to tree in loops, with the windfall of untold centuries piled criss-cross below higher than a house. The men grumbled.They had not bargained on this kind of voyaging. Once down on the west side of the Great Divide, there were the Forks.MacKenzie's instincts told him the northbranch looked the better way, but the old guide had said only the south branch would lead to the Great River beyond the mountains, and they turned up Parsnip River through a marsh of beaver meadows, which MacKenzie noted for future trade. It was now the 3rd of June.MacKenzie ascended a. mountain to look along the forward path. When he came down with McKay and the Indian Cancre, no canoe was to be found.MacKenzie sent broken branches drifting down stream as a signal and fired gunshot after gunshot, but no answer!Had the men deserted with boat and provisions?Genuinely alarmed, MacKenzie ordered McKay and Cancre back down the Parsnip, while he went on up stream. Whichever found the canoe was to fire a gun.For a day without food and in drenching rains, the three tore through the underbrush shouting, seeking, despairing till strength vas ethausted and moccasins worn to tattersBarefoot and soaked, MacKenzie was just lying down for the night when a crashing 64 "The Coming of the Pedlars" echo told him McKay had found the deserters. They had waited till he had disappeared up the mountain, then headed the canoe north and drifted down stream. -

774G Forks Walkingtour.Indd

Walking Tours Walking Tours A word about using this guide... MINI-TOURS This publication is comprised of six mini-tours, arranged around the important historical and developmental stories of The Forks. Each of these tours includes: • a brief introduction • highlights of the era’s history • a map identifying interpretive plaques, images and locations throughout The Forks that give you detailed information on each of these stories The key stories are arranged so you can travel back in time. Start by familiarizing yourself with the present and then move back to the past. GET YOUR BEARINGS If you can see the green dome of the railway station and the green roof of the Hotel Fort Garry, you are looking west. If you are looking at the red canopy of the Scotiabank Stage, you are pointed north. If you see the wide Red River, you are looking east and by looking south you see the smaller Assiniboine River. 3 Take Your Place! If you are a first time visitor, take this opportunity to let your eyes and imagination wander! Welcome Imagine your place among the hundreds of immigrant railway Newcomer! workers toiling in one of the industrial buildings in the yards. You hear dozens of foreign languages, strange to your ear, as you You are standing on land that has, for thousands of years, repair the massive steam engines brought into the yards and been a place of great activity. It has seen the comings and hauled into the roundhouse. Or maybe you work in the stables, goings – of massive glacial sheets of ice – of expansive lakes caring for the hundreds of horses used in pulling the wagons that teeming with wildlife of every description – of new lands transport the boxcars full of goods to the warehouse district nearby. -

A Chronological Outline of the Evolution of the Various Fur Trade and Colonial Establishments Near the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers

A Chronological Outline of the Evolution of the Various Fur Trade and Colonial Establishments near the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. 16*10-1336. The North West and Hudson's Bay Companies first began in earnest to permanently occupy the Red River country during the last decade of the 18th Century. Fur Trade posts belonging to both companies sprang up near the forks of the Pembina and Red River and likewise near the junction of the Assiniboine and Souris, and the Assiniboine and Qu'appelle Rivers. The abundance and availibility of 'country provisions' principally pemican, drew both companies to the Red River. The 'Forks' of the Red and Assiniboine was an important mee 1 meeting place frequented by the brigades of both companies. Neither the Nort West or Hudson's **ay Companies established a permanent post at the Forks before 16*10. The f$rst to re-occupy the Forks(the French had built Fort Rouge at the Forks in 1738) was John Wills for the North 2 West Company in 1810-1811. Prior to 16*10, the Nort West Company's Red River Department was centred at Pembina (Alex. Henry 1600-08 and Daniel Mckenzie 1808-09). £he threat of a confrontation with the hostile Dakota Sioux forced Mckenzie's successor, John WTills, northward to the Forks in 3 1810. Wills positioned his post at tjie junction of the Red and Assiniboine, on that point of land formed by the west bank of the Red and the north bank of the Assiniboine. The Earl of Selkirk's plan to establish an agricul tural Rolony in the western interior of British Nort Amer ica began to take shape in 1811. -

Fort Garry Campus Food Services

What’s Going On In Winnipeg? Folklorama Location: All Over Winnipeg! Telephone No.: (204) 982-6210 Folklorama is a 2 week multicultural festival celebrating the ethnic heritage of people who call Winnipeg home. It features 20 pavilions each week, with each pavilion showcasing the food, dance, music, dress and customs of a particular country. It’s an amazing time! Winnipeg Goldeyes Baseball Location: Canwest Park (1 Portage Avenue East) Telephone No.: (204) 982-2273 th th Watch the Winnipeg Goldeyes take on the Joliet JackHammers or Schaumburg Flyers in Northern League baseball action on August 6 to 9 . 1. Downtown & St. Boniface Portage Avenue Winnipeg Art Gallery Location: 300 Memorial Boulevard Telephone No.: (204) 786-6641 WAG, Manitoba’s premier gallery, features art from Canada and abroad. Current exhibitions include: Canada on Canvas: A Private Collection at The WAG, The Sterling Quality: Four Centuries of Silver, Allyson Mitchell: Ladies Sasquatch, Inuit Dolls of the Kivalliq and Joe Fafard. Broadway Dalnavert Museum Location: 61 Carlton Street Telephone No.: (204) 943-2835 Dalnavert Museum is the Victorian-era home of Sir Hugh John Macdonald, son of Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first Prime Minister. Fort Garry Hotel Location: 222 Broadway Telephone No.: (204) 942-8251 Built in 1913, this château-style hotel is the ultimate in luxury. The hotel features a lavish health spa and decadent Sunday brunch. Manitoba Legislative Building Location: 450 Broadway Telephone No.: (204) 945-4243 The Manitoba Legislative Building, completed in 1920, is home to the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba and Manitoba’s famous Golden Boy. Upper Fort Garry Location: 212 Main Street (at the corner of Main Street and Broadway) Telephone No.: (204) 947-5073 Rebuilt in 1836, Upper Fort Garry – a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post – was the site of the Red River Resistance led by Louis Riel. -

The Influence of the Hudson's Bay Company in the Exploration And

THE INFLUENCE OF THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY IN THE EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT OF THE RED RIVER VALLEY OF THE NORTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Earla Elizabeth Croll In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major Department: History, Philosophy, and Religious Studies May 2014 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title THE INFLUENCE OF THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY IN THE EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT OF THE RED RIVER VALLEY OF THE NORTH By Earla Elizabeth Croll The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. Mark Harvey Chair Dr. Gerritdina Justitz Dr. Larry Peterson Dr. Holly Bastow-Shoop Approved: 7/21/2014 Dr. John K. Cox Date Department Chair ABSTRACT THE INFLUENCE OF THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY IN THE EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT OF THE RED RIVER VALLEY OF THE NORTH As beaver became scarcer in the east, the quest for Castor Canadensis sent traders into the northern plains. Reluctant explorers, traders looked for easier access and cheaper means of transport. Initially content to wait on the shores of the Bay, HBC was forced to meet their competitors in the natives’ homelands. The Red River Valley was easily accessed from Hudson’s Bay, becoming the center of the fur trade in the northern plains. HBC helped colonize the first permanent settlement west of the Great Lakes in the Red River Valley. -

Wedding Package 2018

1 Wedding Package 2018 All food, beverages and billable items are subject to applicable taxes and a 15% gratuity. 2 OUR VENUE Fort Gibraltar has been a historic gathering place since 1809; make your special event part of our history. We offer a beautiful setting for a unique and inspired wedding that is personally yours. Situated on the banks of the Red River, only two minutes from Portage and Main, Fort Gibraltar’s natural beauty will take you back two hundred years to the period of the voyageurs and the fur trade era of the Northwest. Indoor and outdoor ceremonies and receptions are made even more special with historical music and entertainment options and are highlighted by our natural, very special outdoor settings. Beautiful tent weddings set up on our park like grounds on the banks of the Red River with one of the most picturesque settings within Winnipeg city limits. For Social Media please visit Virtual Tour http://goo.gl/maps/NlCeI Facebook www.facebook.com/FortGibraltar Website www.fortgibraltar.com Twitter www.twitter.com/fortgibraltar Pinterest www.pinterest.com/fortgibraltar/ Youtube www.youtube.com/thefortgibraltar Google+ http://goo.gl/DFOOsy All food, beverages and billable items are subject to applicable taxes and a 15% gratuity. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS RECEPTION RENTAL FEES ....................................................................................................... 4 CEREMONY INFORMATION ..................................................................................................... 6 HORS D’OEUVRES .................................................................................................................... -

The Selkirk Settlement

,. ' 1- ~' THE SELKIRK SETTLEMENT AND THE SETTLERS. A CONCISE HISTORY OF THE RED RIVER COUNTRY FRO :t.

1990 Investigations at Fort Gibraltar I

I I 1990 INVESTIGATIONS I AT FORT GIBRALTAR I: I I THE FORKS PUBLIC I ARCHAEOLOGY PROJECT Sid Kroker Barry B. Greco Sharon Thomson ABSTRACT During the summer of 1990, funding from Canadian Parks Service, The Forks Renewal Corporation and Historic Resources Branch of Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Recreation (now designated Culture, Heritage and Citizenship) enabled the implementation of a 16 week Public Archaeology Program. The pro- gram provided a hands-on archaeological experience for more than 560 individuals, through general public partidpation and school programcomponents. A total of 42,480 visitors came to watch archaeology-inaction. The project was conducted by a staff of professional archaeologists, assisted by a partiapant coordinator and two tour guides. A ratio of two partiapants for each professional was maintained, both in the excavation component and the laboratory component. This ratio resulted in close supervision and the maintenance of profes- sional standards. The enthusiasm and intense concentration displayed by the participants resulted in work of very high quality. The excavation was a continuation of the 1989 project conducted at The Forks National Historic Site. The 1990 project uncovered further evidence of five major events. The major natural event, the flood of 1826, was identified in the soil stratiffa~hv.The four cultural events. documented bv stratiera~hv"',and recovered artifac'ts,'w~rethe~ailia~period (18&1988), theco&truction of the B&gBuilding (1888-1889), the Hudson's Bav Companv Experimental Farm (1836-1848) and the Fort ~ibralkrI Period (18161816). 3tn;ctur;l remains of one of the buildings of the fur trade post were recorded.