Brochure-Heritage-Beneath-Your-Feet.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downtown Old St. Boniface

Oseredok DISRAELI FWY Heaton Av Chinese GardensJames Av Red River Chinatown Ukrainian George A Hotels Indoor Walkway System: Parking Lot Parkade W College Gomez illiam A Gate Cultural Centre Museums/Historic Structures Main Underground Manitoba Sports Argyle St aterfront Dr River Spirit Water Bus Canada Games Edwin St v Civic/Educational/Office Buildings Downtown Winnipeg & Old St. Boniface v Hall of Fame W Sport for Life Graham Skywalk Notre Dame Av Cumberland A Bannatyne A Centre Galt Av i H Services Harriet St Ellen St Heartland City Hall Alexander Av Shopping Neighbourhoods Portage Skywalk Manitoba Lily St Gertie St International Duncan St Museum Malls/Dept. Stores/Marketplaces St. Mary Skywalk Post Office English School Council Main St The v v Centennial Tom Hendry P Venues/Theatres Bldg acific A Currency N Frances St McDermot A Concert Hall Theatre 500 v Province-Wide Arteries 100 Pantages Building Entrances Pharmacy 300 Old Market v Playhouse Car Rental Square Theatre Amy St Walking/Cycling Trails Adelaide St Dagmar St 100 Mere Alexander Dock City Route Numbers Theatre James A Transit Only Spence St Hotel Princess St (closed) Artspace Exchange Elgin Av aterfront Dr Balmoral St v Hargrave St District BIZ The DistrictMarket A W Cinematheque John Hirsch Scale approx. Exchange 200 John Hirsch Pl Notre Dame A Theatre v Fort Gibraltar 100 0 100 200 m Carlton St Bertha St and Maison Edmonton St National Historic Site Sargent Av Central District du Bourgeois K Mariaggi’s Rorie St ennedy St King St Park v 10 Theme Suite Towne Bannatyne -

Bush Artist Fellows

Bush Artist Fellows AY_i 1/14/03 10:05 AM Page i Bush Artist Fellows AY 1-55 1/14/03 10:07 AM Page 1 AY 1-55 1/14/03 10:07 AM Page 2 Bush Artist Fellows CHOREOGRAPHY MULTIMEDIA PERFORMANCE ART STORYTELLING M. Cochise Anderson Ananya Chatterjea Ceil Anne Clement Aparna Ramaswamy James Sewell Kristin Van Loon and Arwen Wilder VISUAL ARTS: THREE DIMENSIONAL Davora Lindner Charles Matson Lume VISUAL ARTS: TWO DIMENSIONAL Arthur Amiotte Bounxou Chanthraphone David Lefkowitz Jeff Millikan Melba Price Paul Shambroom Carolyn Swiszcz 2 AY 1-55 1/14/03 10:07 AM Page 3 Bush Artist Fellowships stablished in 1976, the purpose of the Bush Artist Fellowships is to provide artists with significant E financial support that enables them to further their work and their contributions to their communi- ties. An artist may use the fellowship in many ways: to engage in solitary work or reflection, for collabo- rative or community projects, or for travel or research. No two fellowships are exactly alike. Eligible artists reside in Minnesota, North and South Dakota, and western Wisconsin. Artists may apply in any of these categories: VISUAL ARTS: TWO DIMENSIONAL VISUAL ARTS: THREE DIMENSIONAL LITERATURE Poetry, Fiction, Creative Nonfiction CHOREOGRAPHY • MULTIMEDIA PERFORMANCE ART/STORYTELLING SCRIPTWORKS Playwriting and Screenwriting MUSIC COMPOSITION FILM • VIDEO Applications for all disciplines will be considered in alternating years. 3 AY 1-55 1/14/03 10:07 AM Page 4 Panels PRELIMINARY PANEL Annette DiMeo Carlozzi Catherine Wagner CHOREOGRAPHY Curator of -

The Selkirk Settlement and the Settlers. a Concise History of The

nus- C-0-i^JtJL^e^jC THE SELKIRK SETTLEMENT AND THE SETTLERS. ACONCISK HISTORY OF THE RED RIVER COUNTRY FROM ITS DISCOVEEY, Including Information Extracted from Original Documents Lately Discovered and Notes obtained from SELKIRK SETTLEMENT COLONISTS. By CHARLES N, BELL, F.R.G-.S., Honorary Corresponding Member of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, Hamilton Association, Chicago Academy ot Science, Buffalo Historical Society, Historian of Wolseley's Expeditionary Force Association, etc., etc. Author ot "Our Northern Waters," "Navigation of Hudson's Bay and Strait," "Some Historical Names and - Places ot Northwest Canada,' "Red River Settlement History,"" Mound-builders in Manitoba." "Prehistoric Remains in the Canadian Northwest," "With the Half-breed Buffalo Hunters," etc., etc. Winnipeg : PRINTED Vf THE OFFICE 01 "THE COMHERCIA] ," J klftES ST. BAST. issT. The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE COLLECTION of CANADIANA Queen's University at Kingston c (Purchased primj^arm Pkra Qplkctiaru at Quun's unwersii/ oKmc J GfakOurwtt 5^lira cImst- >• T« Selkirk Settlement and the Settlers." By CHARLES X. BELL, F.R.G.S. II [STORY OF II B Ti: IDE. Red River settlement, and stood at the north end of the Slough at what is now About 17.'><i LaN erandyre, a French-Can- Donald adian, established on the Red river a known as Fast Selkirk village. Mr. colonists, in- trading post, which was certainly the first Murray, one of the Selkirk of occasion that white men had a fixed abode forms me that he slept at the ruins in the lower Red River valley. After 1770 such a place in the fall of 1815, when the English merchants and traders of arriving in this country. -

S C H O O L Program

SCHOOL PROGRAM 2020 INTRODUCTION We invite you to learn about Fort Gibraltar’s influence over the cultural development of the Red River settlement. Delve into the lore of the French Canadian voyageurs who paddled across the country, transporting trade-goods and the unique customs of Lower Canada into the West. They married into the First Nations communities and precipitated the birth of the Métis nation, a unique culture that would have a lasting impact on the settlement. Learn how the First Nations helped to ensure the success of these traders by trapping the furs needed for the growing European marketplace. Discover how they shared their knowledge of the land and climate for the survival of their new guests. On the other end of the social scale, meet one of the upper-class managers of the trading post. Here you will get a glimpse of the social conventions of a rapidly changing industrialized Europe. Through hands-on demonstrations and authentic crafts, learn about the formation of this unique community nearly two hundred years ago. Costumed interpreters will guide your class back in time to the year 1815 to a time of immeasurable change in the Red River valley. 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Fort Gibraltar Admission 866, Saint-Joseph St. Guided Tour Managed by: Festival du Voyageur inc. School Groups – $5 per student Phone: 204.237.7692 Max. 80 students, 1.877.889.7692 Free admission for teachers Fax: 204.233.7576 www.fortgibraltar.com www.heho.ca Dates of operation for the School Program Reservations May 11 to June 26, 2019 Guided tours must be booked at least one week before your outing date. -

Norway House

Norway House Economic Opportunity and The Rise of Community 1825-1844 James McKillip Norway House Economic Opportunity and The Rise of Community 1825-1844 James McKillip Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © James McKillip, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the Hudson’s Bay Company depot that was built at Norway House beginning in 1825 created economic opportunities that were sufficiently strong to draw Aboriginal people to the site in such numbers that, within a decade of its establishment, the post was the locus of a thriving community. This was in spite of the lack of any significant trade in furs, in spite of the absence of an existing Aboriginal community on which to expand and in spite of the very small number of Hudson’s Bay Company personnel assigned to the post on a permanent basis. Although economic factors were not the only reason for the development of Norway House as a community, these factors were almost certainly primus inter pares of the various influences in that development. This study also offers a new framework for the conception and construction of community based on documenting day-to-day activities that were themselves behavioural reflections of intentionality and choice. Interpretation of these behaviours is possible by combining a variety of approaches and methodologies, some qualitative and some quantitative. By closely counting and analyzing data in archival records that were collected by fur trade agents in the course of their normal duties, it is possible to measure the importance of various activities such as construction, fishing and hunting. -

Vanguards of Canada

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY WiLLARD FiSKE Endowment """"""" '""'"'^ E 78.C2M162" Vanguards of Canada 3 1924 028 638 488 A Cornell University S Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028638488 VANGUARDS OF CANADA BOOKS The Rev. John Maclean, M.A., Ph.D., B.D. Vanguards of Canada By JOHN MACLEAN, M.A., Ph.D.. D.D. Member of the British Association, The American Society for the Advance- ment of Science, The American Folk-Lore Society, Correspondent of The Bureau of Ethnology, Washington; Chief Archivist of the Methodist Church, Canada. B 13 G TORONTO The Missionary Society of the Methodist Church The Young People's Forward Movement Department F. C. STEPHENSON, Secretary 15. OOPTRIGHT, OanADA, 1918, BT Frboeriok Clareb Stbfhekgon TOROHTO The Missionary Society of the Methodist Church The Young People's Forward Movement F. 0. Stephenson , Secretary. PREFACE In this admirable book the Rev. Dr. Maclean has done a piece of work of far-reaching significance. The Doctor is well fitted by training, experience, knowledge and sym- pathy to do this work and has done it in a manner which fully vindicates his claim to all these qualifications. Our beloved Canada is just emerging into a vigorous consciousness of nationhood and is showing herself worthy of the best ideals in her conception of what the hig'hest nationality really involves. It is therefore of the utmost importance that the young of this young nation thrilled with a new sense of power, and conscious of a new place in the activities of the world, should understand thoroughly those factors and forces which have so strikingly combined to give us our present place of prominence. -

Medicine in Manitoba

Medicine in Manitoba THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS /u; ROSS MITCHELL, M.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY LIBRARY FR OM THE ESTATE OF VR. E.P. SCARLETT Medic1'ne in M"nito/J" • THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS By ROSS MITCHELL, M. D. .· - ' TO MY WIFE Whose counsel, encouragement and patience have made this wor~ possible . .· A c.~nowledg ments THE LATE Dr. H. H. Chown, soon after coming to Winnipeg about 1880, began to collect material concerning the early doctors of Manitoba, and many years later read a communication on this subject before the Winnipeg Medical Society. This paper has never been published, but the typescript is preserved in the medical library of the University of Manitoba and this, together with his early notebook, were made avail able by him to the present writer, who gratefully acknowledges his indebtedness. The editors of "The Beaver": Mr. Robert Watson, Mr. Douglas Mackay and Mr. Clifford Wilson have procured informa tion from the archives of the Hudson's Bay Company in London. Dr. M. T. Macfarland, registrar of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba, kindly permitted perusal of the first Register of the College. Dr. J. L. Johnston, Provincial Librarian, has never failed to be helpful, has read the manuscript and made many valuable suggestions. Mr. William Douglas, an authority on the Selkirk Settlers and on Free' masonry has given precise information regarding Alexander Cuddie, John Schultz and on the numbers of Selkirk Settlers driven out from Red River. Sheriff Colin Inkster told of Dr. Turver. Personal communications have been received from many Red River pioneers such as Archbishop S. -

From Wasteland to Utopia: Changing Images of the Canadian in the Nineteeth Century

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1987 From Wasteland to Utopia: Changing Images of the Canadian in the Nineteeth Century R. Douglas Francis University of Calgary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Francis, R. Douglas, "From Wasteland to Utopia: Changing Images of the Canadian in the Nineteeth Century" (1987). Great Plains Quarterly. 424. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/424 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. FROM WASTELAND TO UTOPIA CHANGING IMAGES OF THE CANADIAN WEST IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY R. DOUGLAS FRANCIS It is common knowledge that what one This region, possibly more than any other in perceives is greatly conditioned by what one North America, underwent significant wants or expects to see. Perception is not an changes in popular perception throughout the objective act that occurs independently of the nineteenth century largely because people's observer. One is an active agent in the process views of it were formed before they even saw and brings to one's awareness certain precon the region. 1 Being the last area of North ceived values, or a priori assumptions, that America to be settled, it had already acquired enable one to organize the deluge of objects, an imaginary presence in the public mind. -

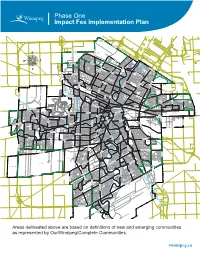

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

Summary of Results: 2018 Manitoba 55 Plus Games

Summary of Results: 2018 Manitoba 55 Plus Games Event Name or Team Region 1 km Predicted Nordic Walk Gold Steen Raymond Interlake Silver Mitchell Lorelie Westman Bronze Klassen Sandra Eastman 3 km Predicted Walk/Run Gold Spiring Britta Assiniboine Park/Fort Garry Silver Reavie Cheryl Parkland Bronze Heidrick Wendy Fort Garry/Assiniboia 16km Predicted Cycle Gold Jones Norma City Centre Silver Hansen Bob City Centre Bronze Moore Bob Westman 5 Pin Bowling Singles Women 55+ Gold MARION SINGLE Central Plains Silver SHARON PROST Westman Bronze SHIRLEY CHUBEY Eastman Women 65+ Gold OLESIA KALINOWICH Parkland Silver BEV VANDAMME Parkland Bronze RHONDA VAUDRY Westman Women 75+ Gold JEAN YASINSKI EK/Transcona Silver VICKY BEYKO Parkland Bronze DONNA GARLAND Westman Women 85+ Gold GRACE JONES Westman Silver EVA HARRIS EK/Transcona Men 55+ Gold DES MURRAY Westman Silver JERRY SKRABEK Ek/Transcona Bronze BERNIE KIELICH Eastman Men 65+ Gold HARVEY VAN DAMME Parkland Silver FRANK AARTS Westman Bronze JAKE ENNS Westman Men 75+ Gold FRANK REIMER Eastman Silver MARRIS BOS Central Plains Bronze NESTOR KALINOWICH Parkland Men 85+ Gold HARRY DOERKSEN EK/Transcona Silver LEO LANSARD EK/Transcona Bronze MELVIN OSWALD Westman 5 Pin Bowling Team 55+ Mixed Gold Carberry 1 Westman Silver OK Gals Westman Bronze Plumas Pin Pals Central Plains 65+ Mixed Gold Carberry 2 Westman Silver Parkland Parkland Bronze Hot Shots Westman 75+ Mixed Gold EK/Transcona EK/Transcona Silver Blumenort Eastman Bronze Strike Force Parkland 8 Ball 55+ Gold Dieter Bonas Assiniboine Park/Fort Garry Silver Rheal Simon Pembina Valley Bronze Guy Jolicoeur Eastman 70+ Gold Alfred Zastre Parkland Silver Denis Gaudet St. -

Pimachiowin Aki Annual Report 2017

Annual Report 2017 Pimachiowin Aki Corporation Pimachiowin Aki Corporation is a non-profit organization working to achieve international recognition for an Anishinaabe cultural landscape in the boreal forest in central Canada as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site. Members of the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation include the First Nations of Bloodvein River, Little Grand Rapids, Pauingassi and Poplar River and the provinces of Manitoba and Ontario The Corporation’s Mission “To acknowledge and support the Anishinaabe culture and safeguard the boreal forest; preserving a living cultural landscape to ensure the well-being of the Anishinaabe who live here and for the benefit and enjoyment of all people.” The Corporation’s Objectives • To create an internationally recognized network of linked protected areas (including aboriginal ancestral lands) which is worthy of UNESCO World Heritage inscription; • To seek support and approval from governments of First Nations, Ontario, Manitoba, and Canada to complete the nomination process and achieve UNESCO designation; • To enhance cooperative relationships amongst members in order to develop an appropriate management framework for the area; and • To solicit governments and private organizations in order to raise funds to implement the objectives of the Corporation. Table of Contents Message from the Co-Chairs ..................................................................................................................................1 Board of -

Historical Representations of Lake Sturgeon by Native and Non-Native Artists

HISTORICAL REPRESENTATIONS OF LAKE STURGEON BY NATIVE AND NON-NATIVE ARTISTS Christopher Hannibal-Paci First Nations Studies University of Northern British Columbia 3333 University Way Prince George, British Columbia Canada, V2N 4Z9 Abstract I Resume Discussions of landscapes in the earliest accounts of traders in northem Ontario and Manitoba depict a land rich in resources. Native people, who lived in these spaces where the Europeans travelled and settled, saw the world through their own eyes. But what did these groups see? This paper discusses changing representations of lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulves cens), noting differences in the stories and images presented by Native and non-Native people. Les discussions sur les paysages du Nord de l'Ontario et du Manitoba retrouvees dans les anciens recits des marchands de I'epoque decrivent un pays riche en ressources naturelles. Les peuples autochtones qui vivaient dans ces grands espaces, visites et colonises par les Europeens, percevaient ce pays bien differemment. Ce texte presente les perceptions changeantes de I'esturgeon des lacs tout en notant les differences entre les images et les contes crees par les autochtones et ceux crees par les blancs. The Canadian Joumal ofNative Studies XVIII, 2(1998):203-232. 204 Christopher Hannibal-Paci Introduction Doctoral research into Cree, Ojibwe and scientific knowledge of lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) in the Lake Winnipeg basin has led to the present study ofsturgeon representations.1 Lake sturgeon is one of seven species of sturgeon, five of which can be found in North America, has always been important to the Native peoples who shared the fish's original range.