The Influence of the Hudson's Bay Company in the Exploration And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1992 Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier Randy William Widds University of Regina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Widds, Randy William, "Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier" (1992). Great Plains Quarterly. 649. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/649 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SASKATCHEWAN BOUND MIGRATION TO A NEW CANADIAN FRONTIER RANDY WILLIAM WIDDIS Almost forty years ago, Roland Berthoff used Europeans resident in the United States. Yet the published census to construct a map of En despite these numbers, there has been little de glish Canadian settlement in the United States tailed examination of this and other intracon for the year 1900 (Map 1).1 Migration among tinental movements, as scholars have been this group was generally short distance in na frustrated by their inability to operate beyond ture, yet a closer examination of Berthoff's map the narrowly defined geographical and temporal reveals that considerable numbers of migrants boundaries determined by sources -

Riel's Council 1869

Riel’s Council 1869 Back row: left to right, Charles Larocque 1, Pierre Delorme, Thomas Bunn, François Xavier Pagée, Ambroise Lépine 2, Jean Baptiste Tourond, Thomas Spence; centre row: Pierre Poitras, John Bruce, Louis Riel, William Bernard O’Donoghue, François Dauphinais; front row : Hugh F. O’Lone and Paul Proulx. John Bruce. (1831-1893) John Bruce, a Metis carpenter, was president of the Provisional Government of Red River in 1869. Born in 1837, (probably at Ile à la Crosse) his parents were Pierre Bruce and Marguerite Desrosiers. He married Angelique Gaudry (Vaudry, Beaudry) the daughter of Pierre Gaudry and Marie-Anne Hughes. He has been described as tall and dark-featured with a sober looking face. He spoke English, French and several Indian languages. He often worked as a legal advocate for the Francophone Metis. He was reportedly fluent in English, French and a number of Indian languages. On October 1869, Bruce was elected President of the Metis National Committee, the first move to resist the annexation by Canada. He resigned in December 1869 when the provisional government was formed. He did serve as the Commissioner of Public Works in Riel’s Provisional Government. He was appointed a judge and magistrate by Archibald the first 1 Now identified as Francois Guilmette. 2 Now identified as Andre Beauchemin. See Norma Jean Hall for a discussion of this photograph at: http://hallnjean.wordpress.com/sailors-worlds/the-red-river-resistance-and-the-creation-of-manitoba/ 1 Lieutenant Governor. After appearing as a witness against Ambroise Lépine in his trial for the murder of Thomas Scott, Bruce and his family moved to Leroy, in what is now North Dakota. -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution Fidler in Context

TABLE OF CONTENTS acknowledgements vii introduction Fidler in Context 1 first journal From York Factory to Buckingham House 43 second journal From Buckingham House to the Rocky Mountains 95 notes to the first journal 151 notes to the second journal 241 sources and references 321 index 351 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION FIDLER IN CONTEXT In July 1792 Peter Fidler, a young surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company, set out from York Factory to the company’s new outpost high on the North Saskatchewan River. He spent the winter of 1792‐93 with a group of Piikani hunting buffalo in the foothills SW of Calgary. These were remarkable journeys. The river brigade travelled more than 2000 km in 80 days, hauling heavy loads, moving upstream almost all the way. With the Piikani, Fidler witnessed hunts at sites that archaeologists have since studied intensively. On both trips his assignment was to map the fur-trade route from Hudson Bay to the Rocky Mountains. Fidler kept two journals, one for the river trip and one for his circuit with the Piikani. The freshness and immediacy of these journals are a great part of their appeal. They are filled with descriptions of regional landscapes, hunting and trading, Native and fur-trade cultures, all of them reflecting a young man’s sense of adventure as he crossed the continent. But there is noth- ing naive or spontaneous about these remarks. The journals are transcripts of his route survey, the first stages of a map to be sent to the company’s head office in London. -

Bourgeois De La Compagnie

LES BOURGEOIS DE LA COMPAGNIE NORD-OUEST RÉCITS DE VOYAGES, LETTRES ET RAPPORTS INÉDITS RELATIFS AU NORD-OUEST CANADIEN PUBLIES AVEC UNE ESQUISSE HISTORIQUE et des Annotations 1A, R. MASSOtf Deuxième Série ' QUÉBEC DE L'IMPRIMERIE GÉNÉRALE A. COTÉ ET <i 1890 RÉCITS DE VOYAGES LETTRES ET RAPPORTS INÉDITS RELATIFS AU NORD-OUEST CANADIEN DEUXIÈME SÉRIE 1. M. John McDonald, Bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord-Ouest. " Autobiographical Notes", 1*791-1816. 2. M. George Keith, Bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord- Ouest. Lettres à l'honorable E. McKenzie: 1807- 1817.—Les départements de la Rivière Mackenzie et du " Lac d'Ours "—Great Bear Lake.—Légendes. 8. M. John Johnston, traiteur libre, du Sault Ste-Marie. " An account of Lake Superior ", 1792-1807. 4. M. Samuel H. "Wilcocke. Narrative of circumstances attending the death of the late Benjamin Frobisher, Esq., a Partner of the North-West Company", 1819. — Luttes contre Lord Selkirk et la Compagnie de la Baie d'Hud- son. 5. M. Duncan Cameron, Bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord-Ouest. " A sketch of the customs, manners and way of living of the Natives in the barren Country àbout Nipi- gon " :—Extraits de son journal, 1804-1805.—La traite avec les sauvages. 6. M. Peter G-xant, Bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord- Ouest. " The Sauteux Indians ", vers 1804. — ri — 7. M. James McKenzie, Bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord-Ouest. Extraits de son journal de 1199. — Le département d'Atkabasca. 8. M. James McKenzie. " Some account of the King's Posts, the Labrador Coast and the Island of Anticosti, by an Indian Trader residing there several years ; with a Descrip tion of the Natives, and the Journal of a trip through those Countries, in 1808, by the same Person." 9. -

Reconstituting Tbc Fur Trade Community of the Assiniboine Basin

Reconstituting tbc Fur Trade Community of the Assiniboine Basin, 1793 to 1812. by Margaret L. Clarke a thesis presented to The University of Winnipeg / The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Winnipeg, Manitoba MARCH 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques 395 WdtïSûeet 395, nn, Wellingtwi WONK1AW WONK1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Ll'brary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disbi'bute or sefl reproduire, prêter, disbiiuer ou copies of this thesis iu microfo~a, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic fomiats. la fome de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format eectronicpe. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur consewe la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE A TksW/Pnicticw ribmitteà to the Faculty of Gruluate Studies of The University of Manitoba in parail fntfülment of the reqaifements of the degrce of brgarct 1. Clarke 1997 (a Permission hm been grantd to the Library of Tbe Univenity of Manitoba to lend or sen copies of this thcsis/practicam, to the National Librory of Canada to micronlm tbb thesis and to lend or seU copies of the mm, and to Dissertritions Abstmcts Intemationai to publish an abtract of this thcsidpracticam. -

The Beaver Club (1785-1827): Behind Closed Doors Bella Silverman

The Beaver Club (1785-1827): Behind Closed Doors Bella Silverman Montreal’s infamous Beaver Club (1785-1827) was a social group that brought together retired merchants and acted as a platform where young fur traders could enter Montreal’s bourgeois society.1 The rules and social values governing the club reveal the violent, racist, and misogynistic underpinnings of the group; its membership was exclusively white and male, and the club admitted members who participated in morally grotesque and violent activities, such as murder and slavery. Further, the club’s mandate encouraged the systematic “othering” of those believed to be “savage” and unlike themselves.2 Indeed, the Beaver Club’s exploitive, exclusive, and violent character was cultivated in private gatherings held at its Beaver Hall Hill mansion.3 (fig. 1) Subjected to specific rules and regulations, the club allowed members to collude economically, often through their participation in the institution of slavery, and idealize the strength of white men who wintered in the North American interior or “Indian Country.”4 Up until 1821, Montreal was a mercantile city which relied upon the fur trade and international import-exports as its economic engine.5 Following the British Conquest of New France in 1759, the fur trading merchants’ influence was especially strong.6 Increasing affluence and opportunities for leisure led to the establishment of social organizations, the Beaver Club being one among many.7 The Beaver Club was founded in 1785 by the same group of men who founded the North West Company (NWC), a fur trading organization established in 1775. 9 Some of the company’s founding partners were James McGill, the Frobisher brothers, and later, Alexander Henry.10 These men were also some of the Beaver Club’s original members.11 (figs. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

Who Was Louis Riel?

Métis Nation of Ontario Who was Louis Riel? Louis, the first child of Louis Riel and Julie Lagimodière, was born on October 22, 1844 in St. Boniface, Manitoba. Louis spent his childhood on the east bank of the Red River, not far from St. Boniface. He grew up among the Métis and was extremely conscious of his identity. At the age of seven, he began his education, eventually studying at the school established in the settlement in 1854 by a Christian brother. With the aim of training priests for the young colony, in 1858, Bishop Tache sent him and two other boys, Daniel McDougall and Louis Schmidt to Montreal to continue their studies. Louis was admitted to the Collège de Montréal where he spent the next eight years studying Latin, Greek, French, English, philosophy and the sciences. Louis proved an excellent student, rising quickly to the top of his class. In January 1864, Louis was overwhelmed with grief by the death of his beloved father whom he had not seen since leaving Red River. A subsequent attitude change prompted his teachers to question Louis’ commitment to a religious vocation. A year later he left his residency at Collège de Montréal to become a day student. But after breaking the rules several times and repeatedly missing class, he was asked to leave both the college and convent. He left College and returned to the Red River in a world fraught with intense political activity and intense nationalism. Louis lived with his aunt, Lucia Riel, and managed to find employment in a law office. -

The Selkirk Settlement and the Settlers. a Concise History of The

nus- C-0-i^JtJL^e^jC THE SELKIRK SETTLEMENT AND THE SETTLERS. ACONCISK HISTORY OF THE RED RIVER COUNTRY FROM ITS DISCOVEEY, Including Information Extracted from Original Documents Lately Discovered and Notes obtained from SELKIRK SETTLEMENT COLONISTS. By CHARLES N, BELL, F.R.G-.S., Honorary Corresponding Member of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, Hamilton Association, Chicago Academy ot Science, Buffalo Historical Society, Historian of Wolseley's Expeditionary Force Association, etc., etc. Author ot "Our Northern Waters," "Navigation of Hudson's Bay and Strait," "Some Historical Names and - Places ot Northwest Canada,' "Red River Settlement History,"" Mound-builders in Manitoba." "Prehistoric Remains in the Canadian Northwest," "With the Half-breed Buffalo Hunters," etc., etc. Winnipeg : PRINTED Vf THE OFFICE 01 "THE COMHERCIA] ," J klftES ST. BAST. issT. The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE COLLECTION of CANADIANA Queen's University at Kingston c (Purchased primj^arm Pkra Qplkctiaru at Quun's unwersii/ oKmc J GfakOurwtt 5^lira cImst- >• T« Selkirk Settlement and the Settlers." By CHARLES X. BELL, F.R.G.S. II [STORY OF II B Ti: IDE. Red River settlement, and stood at the north end of the Slough at what is now About 17.'><i LaN erandyre, a French-Can- Donald adian, established on the Red river a known as Fast Selkirk village. Mr. colonists, in- trading post, which was certainly the first Murray, one of the Selkirk of occasion that white men had a fixed abode forms me that he slept at the ruins in the lower Red River valley. After 1770 such a place in the fall of 1815, when the English merchants and traders of arriving in this country. -

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education As A

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education as a Treaty Right within the Context of Treaty 7 Sheila Carr-Stewart A thesis submitted to the Faculîy of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Administration and Leadership Department of Educational Policy Studies Edmonton, Alberta spring 2001 National Library Bibliothèque nationale m*u ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographk Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Oîîawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenirise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation . In memory of John and Betty Carr and Pat and MyrtIe Stewart Abstract On September 22, 1877, representatives of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Tsuu T'ha and Stoney Nations, and Her Majesty's Govemment signed Treaty 7. Over the next century, Canada provided educational services based on the Constitution Act, Section 91(24). -

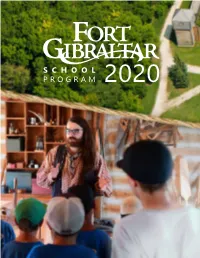

S C H O O L Program

SCHOOL PROGRAM 2020 INTRODUCTION We invite you to learn about Fort Gibraltar’s influence over the cultural development of the Red River settlement. Delve into the lore of the French Canadian voyageurs who paddled across the country, transporting trade-goods and the unique customs of Lower Canada into the West. They married into the First Nations communities and precipitated the birth of the Métis nation, a unique culture that would have a lasting impact on the settlement. Learn how the First Nations helped to ensure the success of these traders by trapping the furs needed for the growing European marketplace. Discover how they shared their knowledge of the land and climate for the survival of their new guests. On the other end of the social scale, meet one of the upper-class managers of the trading post. Here you will get a glimpse of the social conventions of a rapidly changing industrialized Europe. Through hands-on demonstrations and authentic crafts, learn about the formation of this unique community nearly two hundred years ago. Costumed interpreters will guide your class back in time to the year 1815 to a time of immeasurable change in the Red River valley. 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Fort Gibraltar Admission 866, Saint-Joseph St. Guided Tour Managed by: Festival du Voyageur inc. School Groups – $5 per student Phone: 204.237.7692 Max. 80 students, 1.877.889.7692 Free admission for teachers Fax: 204.233.7576 www.fortgibraltar.com www.heho.ca Dates of operation for the School Program Reservations May 11 to June 26, 2019 Guided tours must be booked at least one week before your outing date. -

Tocqueville and Lower Canadian Educational Networks

Encounters on Education Volume 7, Fall 2006 pp. 113 - 130 Tocqueville and Lower Canadian Educational Networks Bruce Curtis Sociology and Anthropology, Carleton University, Canada ABSTRACT Educational history is commonly written as the history of institutions, pedagogical practices or individual educators. This article takes the trans-Atlantic networks of men involved in liberal political and educational reform in the early decades of the nineteenth century as its unit of analysis. In keeping with the author’s interest in education and politics in the British North American colony of Lower Canada, the network is anchored on the person of Alexis de Tocqueville, who visited the colony in 1831. De Tocqueville’s more or less direct connections to many of the men involved in colonial Canadian educational politics are detailed. Key words: de Tocqueville, liberalism, educational networks, monitorial schooling. RESUMEN La historia educativa se escribe comúnmente como la historia de las instituciones, de las prácticas pedagógicas o de los educadores individuales. Este artículo toma, como unidad de análisis, las redes transatlánticas formadas por hombres implicados en las reformas liberales políticas y educativas durante las primeras décadas del siglo XIX. En sintonía con el interés del autor en la educación y la política en la colonia Británico Norteamericana de Lower Canadá, la red se apoya en la persona de Alexis de Tocqueville, que visitó la colonia en 1831. Las relaciones de Tocqueville, más o menos directas, con muchos de los hombres implicados en política educativa del Canadá colonial son detalladas en este trabajo. Descriptores: DeTocqueville, Liberalismo, Redes educativas, Enseñanza monitorizada. RÉSUMÉ L’histoire de l’éducation est ordinairement écrite comme histoire des institutions, des pratiques pédagogiques ou d’éducateurs particuliers.