P0227-P0236.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MOVEMENTS of MARKED SEA and DIVING DUCKS in EUROPE Hugh Boyd

MOVEMENTS OF MARKED SEA AND DIVING DUCKS IN EUROPE Hugh Boyd R inging of dabbling ducks in Europe has helped considerably in discovering the patterns of their distribution and movement through the year. By comparison our knowledge of the behaviour of British species of the tribes Aythyini and Mergini is meagre, chiefly because they are harder to catch outside the breeding season. The numbers marked in Britain have been small, and seem unlikely to be rapidly increased, but ringers in some countries where these ducks breed more plentifully have marked considerably more. Captures of adults, mostly females taken on the nest, have been particularly informative. This paper reviews the results so far apparent. It is based on published and unpublished British records, and on the published material of foreign ringing schemes. I am indebted to the British Trust for Ornithology for permission to use data relating to ducks not ringed at Wildfowl Trust stations. A card index of recoveries compiled by Dr. W. Rydzewski for the International Wildfowl Research Bureau provides a convenient summary of all but the most recent records published abroad, and I am grateful to Dr. Rydzewski and the officers of the Bureau for access to this index. Table I summarises the amount of information obtainable from recoveries and reveals many of its inadequacies. Clearly samples as small as these cannot provide highly reliable and detailed guides to distribution, especially of species which are treated as sporting birds in some countries but not in others. However, by considering the recoveries against the background provided by published studies on the distribution of each species it is possible to form some ideas on the breeding distribution of the populations visiting Britain in winter. -

Red-Breasted Merganser Mergus Serrator of California's Three Mergansers, the Red-Breasted Is the Only One with a Preference Fo

84 Waterfowl — Family Anatidae Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator Of California’s three mergansers, the Red-breasted is the only one with a preference for salt water. The Red-breasted Merganser is a common winter visitor on San Diego Bay but much scarcer at other coastal wetlands and rare on inland lakes. Almost all Red- breasted Mergansers reaching San Diego County are females or immatures with white breasts and rusty heads. Winter: San Diego Bay is by far the principal site for the Red-breasted Merganser in San Diego County. In weekly surveys of the central and south bay from April 1993 to April 1994 Manning (1995) recorded an average of about Photo by Anthony Mercieca 70 in January, the peak month, and a maximum of 117 on 21 January 1994. In weekly surveys of the salt works and 1976 to 2002 the Oceanside Christmas bird count aver- adjacent south bay from February 1993 to February 1994 aged 9.1 Red-breasted Mergansers; from 1980 to 2003 the Stadtlander and Konecny (1994) recorded an average of Rancho Santa Fe count averaged 8.8. about 100 in December, the peak month in that study, and Though the Red-breasted is by far the commonest a maximum of 184 on 29 December 1993. From 1997 to merganser along the coast, in San Diego County it is 2002 the maximum reported in a single atlas square was by far the scarcest inland. Nevertheless, atlas observers 45 in southwestern San Diego Bay (U10) 18 December noted at least 14 individuals inland, with up to six at Lake 1998 (P. -

Hooded Merganser

Mergansers Order Anseriformes Family Anatinae Subfamily Mergini The Mergansers are grouped among the diving ducks but belong to their own subfamily. They are long, slender-bodied diving ducks with long, narrow saw-edged (or serrated - below, center) bills, which help them grip and hold on to fish. Often called “sawbirds,” mergansers are known for their colorful plumage and habits of flying fast & close to the water’s surface. Most species have crests on their heads, which they can hold up or down at will (top photos and below left). In flight, their head, bill, body and tail are held in a straight horizontal line. Mergansers prey on fish, fish eggs and other aquatic animals. The hooded merganser (Lod- phodytes cucullatus) - top right -lives among reeds in Pennsylvania’s swampy, woodland habi- tats using a tree cavity near a pond, lake, river or stream. They will also use a man-made nesting box placed in the proper habitat. The common merganser (Mergus merganser) - top left) needs a wilder, less inhabited site in order to nest. They too are cavity-nesters, but will also nest in a rock pile or even a hole in a stream bank (like a kingfisher). Red-breasted merganser (Mergus serrator) females build her nests in thick vegetation on the ground - though she nests in Canada and Alaska, not in Pennsylvania. But they can be seen on our open rivers during mi- gration. Merganser ducklings from various nests are often grouped to- gether and looked after by a single female.. -

Blood Parasites of Ducks in the British Isles M

Blood parasites of ducks in the British Isles M. J. WORMS and W. A. COOK Summary 243 birds of 16 species of Anatidae have been examined for blood parasites. Microfilariae were found in Teal, Smew and Pintail and Leucocytozoon in Scaup, Wigeon, Pochard and Teal. Parasites in the Smew, Pochard and Wigeon are considered new host records. Attempts at transmission of the Teal filaria were unsuccessful. During 1964 and 1965 the blood of a large certain times during the day or night, number of wild birds has been examined usually coincident with the maximum as part of a survey for avian microfilariae. activity of the arthropod vector, a pheno In the course of these examinations, the menon known as periodicity. During the presence of other blood parasites has been periods when they are absent from the noted and this report records those found peripheral blood they accumulate in the in the family Anatidae. vessels of the lungs and it is therefore to be The birds were obtained from Borough expected that more infected birds will be Fen Decoy, Peakirk, Northants and discovered by examination of this blood. Benington Marsh near Boston, Lincs. In addition to this diurnal periodicity Dr. James Harrison kindly provided lung there may also be a seasonal periodicity. blood smears of birds collected or found Several authors have noted a lower dead in Kent or elsewhere. The majority incidence of detectable parasites during of the samples were collected during the the winter months than in the summer, winter months, a single blood smear being apparently correlated with the sexual taken from the wing vein of the living cycle of the host. -

Smew in San Joaquin County - a First for the Central Valley

Smew in San Joaquin County - a first for the Central Valley Terry Ronneberg, 1035 Wood Thrush Lane, Tracy, CA 95376 Thursday, 20 January 2000, "Smew Day," will always be etched in my mind. The day started offroutinely enough, but ended with a good deal of excitement forme, and temporary disappointment for a couple of outstanding San Joaquin County birders. Events were set in motion that afternoon while I was working in my office. My wife, Jean, called to tell me that a friend, Ev deRusha, who lives out on the Old River north of Tracy, San Joaquin Co., had seen a Smew (Mergellus albel/us) earlier that day. Ev related to Jean thatthis duck didn't look like any other she had ever seen, nor did it look like the Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula) that had visited her place for several days. This bird she declared was a Smew; she was certain ofthat, because she had identified it by finding its picture in her National Geographic Guide to Birds of North America. Ev wanted to know if Jean or I could drive out to have a look. Jean, a kindergarten teacher, could not leave her charges unattended, so she called to ask me if! could verify Ev' s sighting. I felt thatthis must be a case of misidentification, besides I was busy, and there was a staff meeting in an hour. But, sensing this was a serious matter to Jean, I left with some reluctance. I arrived at Ev' s home at approximately 2: 15p.m. hoping I could getthis over quickly and return to work. -

Lophodytes Cucull Atus): Evidence from Genetic, Mark–Recapture, and Comparative Data John M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- ubP lished Research US Geological Survey 2008 Site Fidelity Is an Inconsistent Determinant of Population Structure in the Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucull atus): Evidence from Genetic, Mark–Recapture, and Comparative Data John M. Pearce 1U.S. Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, 1U.S. Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, [email protected] Peter Blums University of Missouri-Columbia, Puxico, Missouri Mark S. Lindberg University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Pearce, John M.; Blums, Peter; and Lindberg, Mark S., "Site Fidelity Is an Inconsistent Determinant of Population Structure in the Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucull atus): Evidence from Genetic, Mark–Recapture, and Comparative Data" (2008). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 808. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/808 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- ubP lished Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Auk 125(3):711–722, 2008 The American Ornithologists’ Union, �����2008. Printed in USA. SITE FIDELITY Is AN INCONSISTENT DETERMINANT OF POPULATION STRUCTURE IN THE HOODED MERGANSER (LOPHODYTES CUCUllATUS): EVIDENCE FROM GENETIC, MARK–RECAPTURE, AND COMPARATIVE DATA JOHN M. PEARCE,1,2,4 PETER BLUMS,3,5 AND MARK S. LINDBERG2 1U.S. Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, 4210 University Drive, Anchorage, Alaska 99508, USA; 2Institute of Arctic Biology and Department of Biology and Wildlife, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775, USA; and 3Gaylord Memorial Laboratory, The School of Natural Resources, University of Missouri-Columbia, Puxico, Missouri 63960, USA Abstract.—The level of site fidelity in birds is often characterized as “high” on the basis of rates of return or homing from mark–recapture data. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Index Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Index" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Index The following index is limited to the species of Anatidae; species of other bird families are not indexed, nor are subspecies included. However, vernacular names applied to certain subspecies that sometimes are considered full species are included, as are some generic names that are not utilized in this book but which are still sometimes applied to par ticular species or species groups. Complete indexing is limited to the entries that correspond to the vernacular names utilized in this book; in these cases the primary species account is indicated in italics. Other vernacular or scientific names are indexed to the section of the principal account only. Abyssinian blue-winged goose. See atratus, Cygnus, 31 Bernier teal. See Madagascan teal blue-winged goose atricapilla, Heteronetta, 365 bewickii, Cygnus, 44 acuta, Anas, 233 aucklandica, Anas, 214 Bewick swan, 38, 43, 44-47; PI. -

A Merganser at Auckland Islands, New Zealand

3 A merganser at Auckland Islands, New Zealand MURRAY WILLIAMS School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, P.O. Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand. E-mail: [email protected] Dedicated to the late Janet Kear, a friend and colleague from afar, whose lifetime work enriched our knowledge and enjoyment of the world’s waterfowl. Abstract The last population of the merganser Mergus australis persisted at Auckland Islands in New Zealand’s Subantarctic until its extermination by specimen collectors in 1902. It is now represented by four duckling specimens, 23 skins of immatures and adults, three skeletons, and a partial cadaver stored in 11 museums. It was the smallest known Mergus, the males weighing c. 660 g and showing little plumage dimorphism from the smaller (c. 530 g) females. Only five published accounts report first-hand observations of its ecology, breeding or distribution. Most likely it occurred as year- round territorial pairs in the larger streams and along the coastal edge at the heads of Auckland Island’s eastern inlets and in Carnley Harbour and fed on both marine and fresh water foods. Its population probably never exceeded 20–30 pairs. The scant records suggest it had a typical summer breeding season. Although its keel area and wing skeleton were reduced relative to its sternum length it was well capable of flapping flight. Key words: Auckland Islands, Auckland Islands Merganser, Mergus australis. A merganser (Family Anatidae, Tribe in 1902 (Alexander 1902; Ogilvie-Grant Mergini) once inhabited the Auckland 1905) was obtained, Polynesians having Islands archipelago, 450 km south of New earlier extirpated the New Zealand Zealand in the subantarctic Southern Ocean and Chatham Island populations. -

Scientific Name: Mergus Albellus Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae Range Habitat Gestation Litter Behavior Reprod

Smew Scientific Name: Mergus albellus Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae The length is 14 to 17.5 inches, the weight: is 1.1 to 2 pounds, and the wingspan is 21.5 to 27 inches The drake (male) smew is striking and unmistakable with a mostly white body marked with a black eye patch, breast bar and v-shaped nape patch beneath the crest. The eyes are black and the wings are dark with large white patches. The hen (female) is smaller than the male and has a chestnut head, white throat, and dark brown eyes. The breast is light grey and the rest of the body is dark grey. Juveniles resemble the hen, but the central wing coverts (coverings) have brown edges. The smew’s black bill has a serrated edge with a hook at the tip. Its legs and webbed feet are grey. As with all ducks, the females molt when the chicks are half grown; the males slightly earlier. The ability to fly is reached by the young and regained by the adults in late summer when the family is then ready to begin the fall migration. Range The smew is a migratory bird with a large global range. During breeding season it stays in the taiga of northern Europe and Asia (evergreen forests of the subarctic region). It winters on sheltered coasts and inland lakes from Central and Southern Europe, Northern Africa, and Southern Russia to China, Japan and as far east as the Western Aleutian Islands. Habitat It inhabits fish-rich freshwater lakes, ponds and rivers along coniferous forests. -

NOTES on SUBFOSSIL ANAHDAE from NEW ZEALAND, INCLUDING a NEW SPECBES of PINK-EARED DUCK MALACORHYNCHUS STOR&S L. OLSON Recei

fM NOTES ON SUBFOSSIL ANAHDAE FROM NEW ZEALAND, INCLUDING A NEW SPECBES OF PINK-EARED DUCK MALACORHYNCHUS STOR&S L. OLSON Received 3 October 1976. SUMMARY OLSON, S. L. 1977. Notes on subfossil Anatidae from New Zealand, including a new species of pink-eared duck Malacorhynchus. Emu 77: 132-135. A new species of pink-eared duck, Malacorhynchus scarletti, is described from subfossil deposits at Pyra- mid Valley, South Island, NZ, and is characterized by larger size. Preliminary observations indicate that subfossil specimens of Biziura from New Zealand are larger and differ qualitatively from B. lobata; for the present, the name Biziura delautouri Forbes, 1892, ought to be retained for the New Zealand form. An erroneous record of Mergus australis is corrected. INTRODUCTION Locality. Pyramid Valley Swamp, near Waikari, During two visits to museums in New Zealand, I North Canterbury, South Island, NZ. examined remains of numerous fossil and subfossil Age. Holocene; the bone-bearing sediments at birds, including those of several extinct species of Pyramid Valley Swamp have been determined by ducks. Of these, the form known as Euryanas finschi radio-carbon dating to be about 3,500 years old was represented by thousands of specimens and I (Gregg 1972). plan to treat its osteology and relationships in a Etymology. I take pleasure in naming this new subsequent study. Three other species are the subject species for R. J. Scarlett, osteologist at the Canter- of the present paper. bury Museum, in recognition of his significant con- tributions to New Zealand palaeornithology. MALACORHYNCHUS Diagnosis. Much larger than M, membranaceus In a report on avian remains from Pyramid Valley (see Table I). -

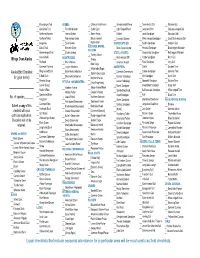

Wings Over Alaska Checklist

Blue-winged Teal GREBES a Chinese Pond-Heron Semipalmated Plover c Temminck's Stint c Western Gull c Cinnamon Teal r Pied-billed Grebe c Cattle Egret c Little Ringed Plover r Long-toed Stint Glacuous-winged Gull Northern Shoveler Horned Grebe a Green Heron Killdeer Least Sandpiper Glaucous Gull Northern Pintail Red-necked Grebe Black-crowned r White-rumped Sandpiper a Great Black-backed Gull a r Eurasian Dotterel c Garganey a Eared Grebe Night-Heron OYSTERCATCHER Baird's Sandpiper Sabine's Gull c Baikal Teal Western Grebe VULTURES, HAWKS, Black Oystercatcher Pectoral Sandpiper Black-legged Kittiwake FALCONS Green-winged Teal [Clark's Grebe] STILTS, AVOCETS Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Red-legged Kittiwake c Turkey Vulture Canvasback a Black-winged Stilt a Purple Sandpiper Ross' Gull Wings Over Alaska ALBATROSSES Osprey Redhead a Shy Albatross a American Avocet Rock Sandpiper Ivory Gull Bald Eagle c Common Pochard Laysan Albatross SANDPIPERS Dunlin r Caspian Tern c White-tailed Eagle Ring-necked Duck Black-footed Albatross r Common Greenshank c Curlew Sandpiper r Common Tern Alaska Bird Checklist c Steller's Sea-Eagle r Tufted Duck Short-tailed Albatross Greater Yellowlegs Stilt Sandpiper Arctic Tern for (your name) Northern Harrier Greater Scaup Lesser Yellowlegs c Spoonbill Sandpiper Aleutian Tern PETRELS, SHEARWATERS [Gray Frog-Hawk] Lesser Scaup a Marsh Sandpiper c Broad-billed Sandpiper a Sooty Tern Northern Fulmar Sharp-shinned Hawk Steller's Eider c Spotted Redshank Buff-breasted Sandpiper c White-winged Tern Mottled Petrel [Cooper's -

A Molecular Phylogeny of Anseriformes Based on Mitochondrial DNA Analysis

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 339–356 www.academicpress.com A molecular phylogeny of anseriformes based on mitochondrial DNA analysis Carole Donne-Goussee,a Vincent Laudet,b and Catherine Haanni€ a,* a CNRS UMR 5534, Centre de Genetique Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Universite Claude Bernard Lyon 1, 16 rue Raphael Dubois, Ba^t. Mendel, 69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France b CNRS UMR 5665, Laboratoire de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Ecole Normale Superieure de Lyon, 45 Allee d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received 5 June 2001; received in revised form 4 December 2001 Abstract To study the phylogenetic relationships among Anseriformes, sequences for the complete mitochondrial control region (CR) were determined from 45 waterfowl representing 24 genera, i.e., half of the existing genera. To confirm the results based on CR analysis we also analyzed representative species based on two mitochondrial protein-coding genes, cytochrome b (cytb) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2). These data allowed us to construct a robust phylogeny of the Anseriformes and to compare it with existing phylogenies based on morphological or molecular data. Chauna and Dendrocygna were identified as early offshoots of the Anseriformes. All the remaining taxa fell into two clades that correspond to the two subfamilies Anatinae and Anserinae. Within Anserinae Branta and Anser cluster together, whereas Coscoroba, Cygnus, and Cereopsis form a relatively weak clade with Cygnus diverging first. Five clades are clearly recognizable among Anatinae: (i) the Anatini with Anas and Lophonetta; (ii) the Aythyini with Aythya and Netta; (iii) the Cairinini with Cairina and Aix; (iv) the Mergini with Mergus, Bucephala, Melanitta, Callonetta, So- materia, and Clangula, and (v) the Tadornini with Tadorna, Chloephaga, and Alopochen.