Smew in San Joaquin County - a First for the Central Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MOVEMENTS of MARKED SEA and DIVING DUCKS in EUROPE Hugh Boyd

MOVEMENTS OF MARKED SEA AND DIVING DUCKS IN EUROPE Hugh Boyd R inging of dabbling ducks in Europe has helped considerably in discovering the patterns of their distribution and movement through the year. By comparison our knowledge of the behaviour of British species of the tribes Aythyini and Mergini is meagre, chiefly because they are harder to catch outside the breeding season. The numbers marked in Britain have been small, and seem unlikely to be rapidly increased, but ringers in some countries where these ducks breed more plentifully have marked considerably more. Captures of adults, mostly females taken on the nest, have been particularly informative. This paper reviews the results so far apparent. It is based on published and unpublished British records, and on the published material of foreign ringing schemes. I am indebted to the British Trust for Ornithology for permission to use data relating to ducks not ringed at Wildfowl Trust stations. A card index of recoveries compiled by Dr. W. Rydzewski for the International Wildfowl Research Bureau provides a convenient summary of all but the most recent records published abroad, and I am grateful to Dr. Rydzewski and the officers of the Bureau for access to this index. Table I summarises the amount of information obtainable from recoveries and reveals many of its inadequacies. Clearly samples as small as these cannot provide highly reliable and detailed guides to distribution, especially of species which are treated as sporting birds in some countries but not in others. However, by considering the recoveries against the background provided by published studies on the distribution of each species it is possible to form some ideas on the breeding distribution of the populations visiting Britain in winter. -

Blood Parasites of Ducks in the British Isles M

Blood parasites of ducks in the British Isles M. J. WORMS and W. A. COOK Summary 243 birds of 16 species of Anatidae have been examined for blood parasites. Microfilariae were found in Teal, Smew and Pintail and Leucocytozoon in Scaup, Wigeon, Pochard and Teal. Parasites in the Smew, Pochard and Wigeon are considered new host records. Attempts at transmission of the Teal filaria were unsuccessful. During 1964 and 1965 the blood of a large certain times during the day or night, number of wild birds has been examined usually coincident with the maximum as part of a survey for avian microfilariae. activity of the arthropod vector, a pheno In the course of these examinations, the menon known as periodicity. During the presence of other blood parasites has been periods when they are absent from the noted and this report records those found peripheral blood they accumulate in the in the family Anatidae. vessels of the lungs and it is therefore to be The birds were obtained from Borough expected that more infected birds will be Fen Decoy, Peakirk, Northants and discovered by examination of this blood. Benington Marsh near Boston, Lincs. In addition to this diurnal periodicity Dr. James Harrison kindly provided lung there may also be a seasonal periodicity. blood smears of birds collected or found Several authors have noted a lower dead in Kent or elsewhere. The majority incidence of detectable parasites during of the samples were collected during the the winter months than in the summer, winter months, a single blood smear being apparently correlated with the sexual taken from the wing vein of the living cycle of the host. -

Scientific Name: Mergus Albellus Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae Range Habitat Gestation Litter Behavior Reprod

Smew Scientific Name: Mergus albellus Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae The length is 14 to 17.5 inches, the weight: is 1.1 to 2 pounds, and the wingspan is 21.5 to 27 inches The drake (male) smew is striking and unmistakable with a mostly white body marked with a black eye patch, breast bar and v-shaped nape patch beneath the crest. The eyes are black and the wings are dark with large white patches. The hen (female) is smaller than the male and has a chestnut head, white throat, and dark brown eyes. The breast is light grey and the rest of the body is dark grey. Juveniles resemble the hen, but the central wing coverts (coverings) have brown edges. The smew’s black bill has a serrated edge with a hook at the tip. Its legs and webbed feet are grey. As with all ducks, the females molt when the chicks are half grown; the males slightly earlier. The ability to fly is reached by the young and regained by the adults in late summer when the family is then ready to begin the fall migration. Range The smew is a migratory bird with a large global range. During breeding season it stays in the taiga of northern Europe and Asia (evergreen forests of the subarctic region). It winters on sheltered coasts and inland lakes from Central and Southern Europe, Northern Africa, and Southern Russia to China, Japan and as far east as the Western Aleutian Islands. Habitat It inhabits fish-rich freshwater lakes, ponds and rivers along coniferous forests. -

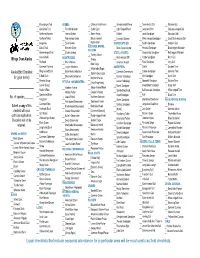

Wings Over Alaska Checklist

Blue-winged Teal GREBES a Chinese Pond-Heron Semipalmated Plover c Temminck's Stint c Western Gull c Cinnamon Teal r Pied-billed Grebe c Cattle Egret c Little Ringed Plover r Long-toed Stint Glacuous-winged Gull Northern Shoveler Horned Grebe a Green Heron Killdeer Least Sandpiper Glaucous Gull Northern Pintail Red-necked Grebe Black-crowned r White-rumped Sandpiper a Great Black-backed Gull a r Eurasian Dotterel c Garganey a Eared Grebe Night-Heron OYSTERCATCHER Baird's Sandpiper Sabine's Gull c Baikal Teal Western Grebe VULTURES, HAWKS, Black Oystercatcher Pectoral Sandpiper Black-legged Kittiwake FALCONS Green-winged Teal [Clark's Grebe] STILTS, AVOCETS Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Red-legged Kittiwake c Turkey Vulture Canvasback a Black-winged Stilt a Purple Sandpiper Ross' Gull Wings Over Alaska ALBATROSSES Osprey Redhead a Shy Albatross a American Avocet Rock Sandpiper Ivory Gull Bald Eagle c Common Pochard Laysan Albatross SANDPIPERS Dunlin r Caspian Tern c White-tailed Eagle Ring-necked Duck Black-footed Albatross r Common Greenshank c Curlew Sandpiper r Common Tern Alaska Bird Checklist c Steller's Sea-Eagle r Tufted Duck Short-tailed Albatross Greater Yellowlegs Stilt Sandpiper Arctic Tern for (your name) Northern Harrier Greater Scaup Lesser Yellowlegs c Spoonbill Sandpiper Aleutian Tern PETRELS, SHEARWATERS [Gray Frog-Hawk] Lesser Scaup a Marsh Sandpiper c Broad-billed Sandpiper a Sooty Tern Northern Fulmar Sharp-shinned Hawk Steller's Eider c Spotted Redshank Buff-breasted Sandpiper c White-winged Tern Mottled Petrel [Cooper's -

A Molecular Phylogeny of Anseriformes Based on Mitochondrial DNA Analysis

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 339–356 www.academicpress.com A molecular phylogeny of anseriformes based on mitochondrial DNA analysis Carole Donne-Goussee,a Vincent Laudet,b and Catherine Haanni€ a,* a CNRS UMR 5534, Centre de Genetique Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Universite Claude Bernard Lyon 1, 16 rue Raphael Dubois, Ba^t. Mendel, 69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France b CNRS UMR 5665, Laboratoire de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Ecole Normale Superieure de Lyon, 45 Allee d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received 5 June 2001; received in revised form 4 December 2001 Abstract To study the phylogenetic relationships among Anseriformes, sequences for the complete mitochondrial control region (CR) were determined from 45 waterfowl representing 24 genera, i.e., half of the existing genera. To confirm the results based on CR analysis we also analyzed representative species based on two mitochondrial protein-coding genes, cytochrome b (cytb) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2). These data allowed us to construct a robust phylogeny of the Anseriformes and to compare it with existing phylogenies based on morphological or molecular data. Chauna and Dendrocygna were identified as early offshoots of the Anseriformes. All the remaining taxa fell into two clades that correspond to the two subfamilies Anatinae and Anserinae. Within Anserinae Branta and Anser cluster together, whereas Coscoroba, Cygnus, and Cereopsis form a relatively weak clade with Cygnus diverging first. Five clades are clearly recognizable among Anatinae: (i) the Anatini with Anas and Lophonetta; (ii) the Aythyini with Aythya and Netta; (iii) the Cairinini with Cairina and Aix; (iv) the Mergini with Mergus, Bucephala, Melanitta, Callonetta, So- materia, and Clangula, and (v) the Tadornini with Tadorna, Chloephaga, and Alopochen. -

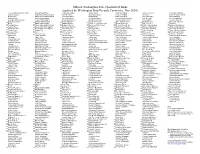

WBRC Review List 2020

Official Washington State Checklist of Birds (updated by Washington Bird Records Committee, Nov 2020) __Fulvous Whistling-Duck (1905) __White-throated Swift __Long-tailed Jaeger __Nazca Booby __Tropical Kingbird __Dusky Thrush (s) __Tricolored Blackbird __Emperor Goose __Ruby-throated Hummingbird __Common Murre __Blue-footed Booby __Western Kingbird __Redwing __Brown-headed Cowbird __Snow Goose __Black-chinned Hummingbird __Thick-billed Murre __Brown Booby __Eastern Kingbird __American Robin __Rusty Blackbird __Ross’s Goose __Anna’s Hummingbird __Pigeon Guillemot __Red-footed Booby __Scissor-tailed Flycatcher __Varied Thrush __Brewer’s Blackbird __Gr. White-fronted Goose __Costa’s Hummingbird __Long-billed Murrelet __Brandt’s Cormorant __Fork-tailed Flycatcher __Gray Catbird __Common Grackle __Taiga Bean-Goose __Calliope Hummingbird __Marbled Murrelet __Pelagic Cormorant __Olive-sided Flycatcher __Brown Thrasher __Great-tailed Grackle __Brant __Rufous Hummingbird __Kittlitz’s Murrelet __Double-crested Cormorant __Greater Pewee (s) __Sage Thrasher __Ovenbird __Cackling Goose __Allen’s Hummingbird (1894) __Scripps’s Murrelet __American White Pelican __Western Wood-Pewee __Northern Mockingbird __Northern Waterthrush __Canada Goose __Broad-tailed Hummingbird __Guadalupe Murrelet __Brown Pelican __Eastern Wood-Pewee __European Starling (I) __Golden-winged Warbler __Trumpeter Swan __Broad-billed Hummingbird __Ancient Murrelet __American Bittern __Yellow-bellied Flycatcher __Bohemian Waxwing __Blue-winged Warbler __Tundra Swan __Virginia Rail -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

P0227-P0236.Pdf

THE SEXUAL BEHAVIOR AND SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE HOODED MERGANSER PAUL A. JOHNSGARD T has been over 15 years since Delacour and Mayr (1945) first urged that the I mergansers (Mergzzs) and the goldeneye-Bufflehead group (Bucephala) be merged into a single tribe (Mergini) rather than being maintained in separate subfamilies (Aythyinae and Merginae) . Their reasons for this change were several, and included such points as the similarities in the downy young, female color patterns, occurrence of wild hybrids between the two genera, and tracheal structure. Indeed, except for the shape of the bill in these two groups there is no good means of distinguishing the two subfamilies. As Delacour and Mayr pointed out, bill shape and structure is highly adaptive and should not be used for the erection of major taxonomic categories. However, these two subfamilies are still upheld in the fifth edition of the AOU Check-list. Delacour and Mayr described the general similarities in the sexual behavior of lMergus and Bucephala, but no one has yet had the opportunity of critically comparing the behavior of most species in the two groups. Myres (1957,1959a, 1959b) reviewed well the behavior of the Bucephala species, but was not for- tunate enough to compare directly copulatory behavior in this genus and Mer- gus. He has, however, provided detailed descriptions of courtship and copulation in the Common Goldeneye (B. clangula) , Barrows’ Goldeneye (B. islandica) , and Bufflehead (B. albeola) . The behavior of the Common Goldeneye has also recently been described by Dane et al. (1959) and Lind (1960). I have been able to observe closely courtship display in all three species of Bucephala and in four species of Mergus, including the Hooded Merganser (M. -

Cavity-Nesting Ducks: Why Woodpeckers Matter Janet Kear

Cavity-nesting ducks: why woodpeckers matter Janet Kear Goosander Mergus merganser Rosemary Watts/Powell ABSTRACT This paper poses a number of related questions and suggests some answers.Why were there no resident tree-hole-nesting ducks in Britain until recently? Why is the Black Woodpecker Dryocopus martius not found in Britain? Could the supply of invertebrate food items, especially in winter, be responsible for the distribution of woodpeckers in western Europe? It is concluded that, in Europe, only the Black Woodpecker can construct holes large enough for ducks to nest in, and that this woodpecker does not occur in Britain & Ireland because of the absence of carpenter ants Campanotus. A plea is made for the global conservation of dead and dying timber, since it is vital for the biodiversity of plants, insects, woodpeckers and ducks. irdwatchers, at least in Britain, tend to surface-feeding ducks (Anatini), including think of ducks as nesting in the open and those which we used to call ‘perching ducks’, Bon the ground, but cavity-nesting is actu- and in the seaducks (Mergini). ally normal, if not obligatory, in almost one- Because ducks are incapable of making holes third of the 162 members of the wildfowl family for themselves, however, they must rely on (Anatidae). Geffen & Yom-Tov (2001) suggested natural agents for the construction of nest cavi- that hole-nesting has evolved independently at ties, and this dependence has profound implica- least three times within the group. I think that it tions for their lifestyles, breeding productivity is more likely to have arisen five or six times; and conservation. -

Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia

I TheSite Guide I Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia by Brian M. Kautesk Location Downtown Vancouver, B.C. totem poles, and other historical art•- facts. Description Stanley Park is a multi-use Access From Vancouver International recreationalpark, adjacent to downtown and residential Vancouver, and situated Airport drive north through the c•ty to on a peninsulajutting directly into Van- the downtownarea. Stanley Park is easdy couver Harbour (Burrard Inlet). The found, being that large green patch •n shoreline, totally accessibleby over 5 the center of any Vancouver City map miles of paved seawall promenade, To avoid traffic congestion,approaches is mainly rocky, with a few areas of to the park should be made either wa mudflats, and two public beaches.This Beach Avenue, or Burrard and Georloa walkway permitsexceptional sea-birding Streets. I recommend the latter for from shore. The water around the park those following my birding itinerary, is deep and cold. The main part of outlined below. the park is second growth forest, pre- Accommodations No problemsof course, dominantly Douglas-fir, Western Red being in the heart of a major city In Cedar, Western Hemlock, Broadleaf pleasant weather, various concession Maple, with Vine Maple and Red Alder booths throughout the park are open in openings, and a general understory Camping is not allowed in the park of Salal and Salmonberry (a magnet for hummingbirds in April). There are Birdwatching Long known as a prime many trails that go deep into the birding area, it has been only in the secludedwoods, where determined bird- most recent years that the park has ers can, with time, find the Hutton's been studiedmethodically and its secrets Vireo. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Contents, Preface, & Introduction Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Contents, Preface, & Introduction" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 2. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DUCKS, GEESE, and SWANS of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Revised Edition Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World By Paul A. Johnsgard The only one-volume comprehensive survey of the family Anatidae available in English, this book combines lavish illustration with the most recent information on the natural history, current distribution and status, and identification of all the species. After an introductory discussion of the ten tribes of Anatidae, separate accounts follow for each of the nearly 150 recognized species. These include scientific and vernacular names (in French, German, and Spanish as well as English), descrip- tions of the distribution of all recognized subspecies, selected weights and mea- surements, and identification criteria for both sexes and various age classes. -

Diseases of Seaducks in Captivity

Diseases of seaducks in captivity NIGELLA HILLGARTH and JANET KEAR For many years the Wildfowl Trust has Bufflehead Bucephaia albeola are, on the monitored the health of its collections by other hand, notoriously difficult to breed carrying out post-mortem examinations. (Williams 1971), and the Hooded Merganser Detailed records have been kept by J. V. M. cucullatus is only a little easier (Lubbock Beer (1959—1969), by N. A. Wood 1973). (1970-1973), and by M. J. Brown sub The difficulty with which these ducks are sequently. This analysis of the accumulated bred is, to some extent, reflected in the records is the first of a series that will numbers available from the Wildfowl Trust’s describe the cause of death in the various collections at post-mortem. For instance, wildfowl groups. eiders predominate in the records, and saw There are seven genera, and 18 species, of bills are commoner than scoters. However, seaducks (M ergini) including the eiders eggs have been collected on a number of oc (Johnsgard 1960). All except one species in casions from the wild, and hatched artificial habit the higher latitudes of the northern ly, so post-mortem findings from dead dow hemisphere; the rare exception, the Brazilian ny and juvenile birds do exist, even for M erganser Mergus octosetaceus, has never species that have seldom bred in captivity. been maintained for long in captivity. The whole group is generally difficult to keep and to persuade to breed. There are many M aterials reasons for this; seaducks are divers and animal eaters; most of them spend the Post-mortem data from 641 seaducks dying winter, and some breed, on salt water; those between 1959 and 1976 have been examined.