The Dicks Top: the Dicks in the Early 1980S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Austin, Texas

IMPACT OF THE MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY ON AUSTIN, TEXAS APPROVED : Copyright 1983 Phyllis Krantzman This thesis is dedicated to all those musicians who make Austin a very special place for all of the rest of us. Impact of the Music Entertainment Industry on Austin, Texas BY Phyllis Krantzman, B. A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMMUNITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN August, 1983 Acknowledgements Many thanks to Terry Kahn for his patience and genuine support of an unconventional topic for a traditional thesis. Thank you to Dowell Meyers for some excellent suggestions, interesting conversations, and his sincere enthusiasm for the "music scene." Thanks to Rosemin and Genie, in the Graduate Office, of the School of Architecture, for their calm support and the taking and conveying of messages. Many thanks to all my professors through the years who have taught me even when Iresisted learning. And Iespecially and fondly thank all of my respondents. Without your responses, this document would never have been completed. July 11, 1983 V Table of Contents Chapter ppage I Introduction .' 1 References 8 II The Musicians 9 2.1 Introduction 9 2.2 Methodology 9 2.3 Descriptive Demographics 11 2.3.1 Age 11 2.3.2 Education 11 2.3.3 Family Life 11 2.3.4 Occupational Information 13 2.3.5 Migratory Information 15 2.3.6 Perception of Self and Band .... 15 2.4 Socio-Economic Information 17 2.4.1 Significance of the Music Industry 17 2.4.2 Benefits 17 2.4.3 Musical Instruments 19 2.4.4 Sessions Played in the Last Twelve Months 20 2.4.5 Comments from the Musicians ... -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

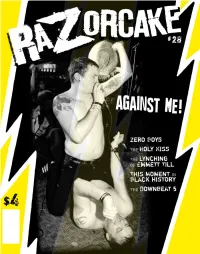

At Thirty-Three, My Anger Hasn't Subsided. It's Gotten

t thirty-three, my anger hasn’t subsided. It’s gotten And to all this, I don’t have a real answer. I don’t think I’m naïve. I deeper. It’s more like magma keeping me warm instead of lava don’t think I’m expecting too much, but it’s hard not to feel shat upon by AAshooting haphazardly all over the place. It’s managed. You see, the world-at-large every step of the way. There are a couple of things that I’ve been able to channel the balled-fist, I’m hitting-walls-and-breaking- temper my anger. First off, when we were doing our math, I got another knuckles anger into something of a long-burning fuse. Oh, I’m angry, but number: sixty-four. That’s how many folks help out Razorcake in some I’m probably one of the calmest angry people you’re likely to meet. I take way, shape, or form on a regular basis. Damn, that’s awesome. Sixty- all of my “fuck yous” and edit. I take my “you’ve got to be fucking kid- four people, without whom this zine would just be a hair-brained ding me”s and take pictures and write. I seek revenge by working my ass scheme. off. Anger, coupled with belief, is a powerful motivator. The second element is a little harder to explain. Recently, I was in an What do I have to be angry about? I don’t think it’s obvious, but we do adjacent town, South Pasadena. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Lexia® Core5® Reading: Comprehension Passages for Levels 12-20

Lexia® Core5® Reading: Comprehension Passages for Levels 12-20 This document contains the full text of all comprehension passages in Levels 12 to 20 of the Lexia Core5 Reading student activities. This resource allows teachers to further scaffold comprehension instruction and activities for students. All comprehension passages in Lexia Core5 Reading have been measured using a number of tools to determine complexity, including Lexile® measures. Based on this analysis, the comprehension passages are appropriately complex for students reading at the grade-level of skills in each program level. For example, all comprehension passages in Levels 13 and 14 (Grade 3 skills) fall within the range of scores deemed appropriate for on-level Grade 3 reading skills. CORE5 LEVEL GRADE LEVEL OF SKILLS LEXILE RANGE 12 Grade 2 420L to 650L 13-14 Grade 3 520L to 820L 16-17 Grade 4 740L to 940L 19-20 Grade 5 830L to 1010L ©2019 Lexia Learning, a Rosetta Stone Company. All rights reserved. Lexile® is a trademark of MetaMetrics rev. 071219 Level 12 | Comprehension US Reading Passages LEVEL 12, UNIT 1 Mixed Up Bear (Narrative) Bear woke up. He had not slept well. “I feel mixed up,” he said with a yawn. He made breakfast. He drank his milk with a fork and used eggs to make a cup of tea. He also put toast on his jam. He washed his face with toothpaste and brushed his teeth with soap. He got dressed. He put his legs in his shirt and his pants on his head. He also put his socks on his hands. -

Austinmusicawards2017.Pdf

Jo Carol Pierce, 1993 Paul Ray, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and PHOTOS BY MARTHA GRENON MARTHA BY PHOTOS Joe Ely, 1990 Daniel Johnston, Living in a Dream 1990 35 YEARS OF THE AUSTIN MUSIC AWARDS BY DOUG FREEMAN n retrospect, confrontation seemed almost a genre taking up the gauntlet after Nelson’s clashing,” admits Moser with a mixture of The Big Boys broil through trademark inevitable. Everyone saw it coming, but no outlaw country of the Seventies. Then Stevie pride and regret at the booking and subse- confrontational catharsis, Biscuit spitting one recalls exactly what set it off. Ray Vaughan called just prior to the date to quent melee. “What I remember of the night is beer onto the crowd during “Movies” and rip- I Blame the Big Boys, whose scathing punk ask if his band could play a surprise set. The that tensions started brewing from the outset ping open a bag of trash to sling around for a classed-up Austin Music Awards show booking, like the entire evening, transpired so between the staff of the Opera House, which the stage as the mosh pit gains momentum audience visited the genre’s desired effect on casually that Moser had almost forgotten until was largely made up of older hippies of a Willie during “TV.” the era. Blame the security at the Austin Stevie Ray and Jimmie Vaughan walked in Nelson persuasion who didn’t take very kindly About 10 minutes in, as the quartet sears into Opera House, bikers and ex-Navy SEALs from with Double Trouble and to the Big Boys, and the Big “Complete Control,” security charges from the Willie Nelson’s road crew, who typical of the proceeded to unleash a dev- ANY HISTORY OF Boys themselves, who were stage wings at the first stage divers. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation “We’re Punk as Fuck and Fuck like Punks:”* Queer-Feminist Counter-Cultures, Punk Music and the Anti-Social Turn in Queer Theory Verfasserin Mag.a Phil. Maria Katharina Wiedlack angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) Wien, Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof.in Dr.in Astrid Fellner Earlier versions and parts of chapters One, Two, Three and Six have been published in the peer-reviewed online journal Transposition: the journal 3 (Musique et théorie queer) (2013), as well as in the anthologies Queering Paradigms III ed. by Liz Morrish and Kathleen O’Mara (2013); and Queering Paradigms II ed. by Mathew Ball and Burkard Scherer (2012); * The title “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks” is a line from the song Burn your Rainbow by the Canadian queer-feminist punk band the Skinjobs on their 2003 album with the same name (released by Agitprop Records). Content 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. “To Sir With Hate:” A Liminal History of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock ….………………………..…… 21 3. “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks:” Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive ………………………….………….. 69 4. “Challenge the System and Challenge Yourself:” Queer-Feminist Punk Rock’s Intersectional Politics and Anarchism……...……… 119 5. “There’s a Dyke in the Pit:” The Feminist Politics of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock……………..…………….. 157 6. “A Race Riot Did Happen!:” Queer Punks of Color Raising Their Voices ..……………..………… ………….. 207 7. “WE R LA FUCKEN RAZA SO DON’T EVEN FUCKEN DARE:” Anger, and the Politics of Jouissance ……….………………………….…………. -

Mar.-Apr.2020 Highlites

Prospect Senior Center 6 Center Street Prospect, CT 06712 (203)758-5300 (203)758-3837 Fax Lucy Smegielski Mar.-Apr.2020 Director - Editor Municipal Agent Highlites Town of Prospect STAFF Lorraine Lori Susan Lirene Melody Matt Maglaris Anderson DaSilva Lorensen Heitz Kalitta From the Director… Dear Members… I believe in being upfront and addressing things head-on. Therefore, I am using this plat- form to address some issues that have come to my attention. Since the cost for out-of-town memberships to our Senior Center went up in January 2020, there have been a few miscon- ceptions that have come to my attention. First and foremost, the one rumor that I would definitely like to address is the story going around that the Prospect Town Council raised the dues of our out-of-town members because they are trying to “get rid” of the non-residents that come here. The story goes that the Town Council is trying to keep our Senior Center strictly for Prospect residents only. Nothing could be further from the truth. I value the out-of-town members who come here. I feel they have contributed significantly to the growth of our Senior Center. Many of these members run programs here and volun- teer in a number of different capacities. They are my lifeline and help me in ways that I could never repay them for. I and the Town Council members would never want to “get rid” of them. I will tell you point blank why the Town Council decided to raise membership dues for out- of-town members. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Waylon Jennings

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 4 About the Guide 5 Pre and Post-Lesson: Anticipation Guide 6 Lesson 1: Introduction to Outlaws 7 Lesson 1: Worksheet 8 Lyric Sheet: Me and Paul 9 Lesson 2: Who Were The Outlaws? 10 Lesson 3: Outlaw Influence 11 Lesson 3: Worksheet 12 Activities: Jigsaw Texts 14 Lyric Sheet: Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way 15 Lesson 4: T for Texas, T for Tennessee 16 Lesson 4: Worksheet 17 Lesson 5: Literary Lyrics 19 “London” by William Blake 20 Complete Tennessee Standards 22 Complete Texas Standards 23 Biographies 3-6 Table of Contents 2 Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s examines how the Outlaw movement greatly enlarged country music’s audience during the 1970s. Led by pacesetters such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Bobby Bare, artists in Nashville and Austin demanded the creative freedom to make their own country music, different from the pop-oriented sound that prevailed at the time. This exhibition also examines the cultures of Nashville and fiercely independent Austin, and the complicated, surprising relationships between the two. Artwork by Sam Yeates, Rising from the Ashes, Willie Takes Flight for Austin (2017) 3-6 Introduction 3 This interdisciplinary lesson guide allows classrooms to explore the exhibition Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s on view at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum® from May 25, 2018 – February 14, 2021. Students will examine the causes and effects of the Outlaw movement through analysis of art, music, video, and nonfiction texts. In doing so, students will gain an understanding of the culture of this movement; who and what influenced it; and how these changes diversified country music’s audience during this time. -

My Guitar Is a Camera

My Guitar Is a Camera John and Robin Dickson Series in Texas Music Sponsored by the Center for Texas Music History Texas State University–San Marcos Gary Hartman, General Editor Casey_pages.indd 1 7/10/17 10:23 AM Contents Foreword ix Steve Miller Acknowledgments xi Introduction xiii Tom Reynolds From Hendrix to Now: Watt, His Camera, and His Odyssey xv Herman Bennett, with Watt M. Casey Jr. 1. Witnesses: The Music, the Wizard, and Me 1 Mark Seal 2. At Home and on the Road: 1970–1975 11 3. Got Them Texas Blues: Early Days at Antone’s 31 4. Rolling Thunder: Dylan, Guitar Gods, and Joni 54 5. Willie, Sir Douglas, and the Austin Music Creation Myth 60 Joe Nick Patoski 6. Cosmic Cowboys and Heavenly Hippies: The Armadillo and Elsewhere 68 7. The Boss in Texas and the USA 96 8. And What Has Happened Since 104 Photographer and Contributors 123 Index 125 Casey_pages.indd 7 7/10/17 10:23 AM Casey_pages.indd 10 7/10/17 10:23 AM Jimi Hendrix poster. Courtesy Paul Gongaware and Concerts West. Casey_pages.indd 14 7/10/17 10:24 AM From Hendrix to Now Watt, His Camera, and His Odyssey HERMAN BENNETT, WITH WATT M. CASEY JR. Watt Casey’s journey as a photographer can be In the summer of 1970, Watt arrived in Aus- traced back to an event on May 10, 1970, at San tin with the intention of getting a degree from Antonio’s Hemisphere Arena: the Cry of Love the University of Texas. Having heard about a Tour.