Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With LOWELL's Real Cre a 'Blueberrybb Naatural And•N T Flavored ISSUES I I I I , I I · , I I· W*E N Ee*

I I with LOWELL'S real cre a 'BlueberryBB NaAtural and•n t Flavored ISSUES I I I I , I I · , I I· _ W*e n ee* By Norman Solomon * This daily satellite-TV feed has a captive audi- * While they're about 25 percent of the U.S. pop- To celebrate the arrival of summer, here's an all- ence of more than 8 million kids in classrooms. ulation, a 1997 survey by the American Society of new episode of "Media Jeopardy!" While it's touted as "a tool to educate and engage Newspaper Editors found that they comprise You probably remember the rules: First, listen young adults in world happenings," the broad- only 11.35 percent of the journalists in the news- carefully to the answer. Then, try to come up with cast service sells commercials that go for nearly rooms of this country's daily papers. the correct question. $200,000 per half-minute -- pitched to advertisers What are racial minorities? as a way of gaining access to "the hardest to reach The first category is "Broadcast News." teen viewers." We're moving into Media Double Jeopardy with What is Channel One? our next category, "Fear and Favor." * On ABC, CBS and NBC, the amount of TV net- work time devoted to this coverage has fallen to * During the 1995-96 election cycle, these corpo- * While this California newspaper was co-spon- half of what it was during the late 1980s. rate parents of major networks gave a total of $3.2 soring a local amateur sporting event with Nike What is internationalnews? million in "soft money" to the national last spring, top editors at the paper killed a staff Democratic and Republican parties. -

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

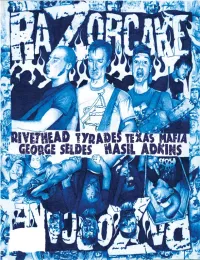

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #19 www.razorcake.com ight around the time we were wrapping up this issue, Todd hours on the subject and brought in visual aids: rare and and I went to West Hollywood to see the Swedish band impossible-to-find records that only I and four other people have RRRandy play. We stood around outside the club, waiting for or ancient punk zines that have moved with me through a dozen the show to start. While we were doing this, two young women apartments. Instead, I just mumbled, “It’s pretty important. I do a came up to us and asked if they could interview us for a project. punk magazine with him.” And I pointed my thumb at Todd. They looked to be about high-school age, and I guess it was for a About an hour and a half later, Randy took the stage. They class project, so we said, “Sure, we’ll do it.” launched into “Dirty Tricks,” ripped right through it, and started I don’t think they had any idea what Razorcake is, or that “Addicts of Communication” without a pause for breath. It was Todd and I are two of the founders of it. unreal. They were so tight, so perfectly in time with each other that They interviewed me first and asked me some basic their songs sounded as immaculate as the recordings. On top of questions: who’s your favorite band? How many shows do you go that, thought, they were going nuts. Jumping around, dancing like to a month? That kind of thing. -

Oh Bondage up Yours

Oh bondage up yours Continue Some people think little girls should be seen and not heard. Iconic vocalist Paulie Styrene certainly isn't, as screeching is the call to arms that opens her band X-Ray Spex debut single Oh Bondage! Up on yours! defiantly testified. For the group so strongly rooted in its era, and it was together so fleeting (they formed in 1976, and disintegrated three years later); For all the simplicity of rapid fire and punk vitriol, not to mention Paulie's vocals (described by one journalist as a sizzling dissonance) - X-Ray Spex feel relevant and important today, forty years later, more than ever. A new book, Dayglo: Paulie Styrene's story tells the story of a woman 'real name Marie Elliott' who has managed to bring a playfully joyful, satirical female voice to a man dominated by nihilism punk. Co-authored with Paulie's daughter Celeste Bell with writer, musician and artist zoe howe, and designed by Laura Findlay, the comprehensive volume combines a series of interviews with Paulie's friends, family and fans with a wealth of gorgeous archival photographs, hand-scrawled lyrical sheets and works of art, flyers and more to create an oral portrait of a woman's history with more than a few stories. Paulie died of breast cancer in 2011 at the age of just fifty-three, so it's left for those who knew her (and those who knew her music) to tell her tales. These contributors make up a formidable list, including Vivienne Westwood, Tessa Politt, John Savage and Thurston Moore (formerly Sonic Youth). -

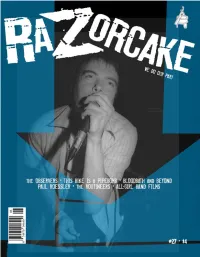

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Download PDF > Riot Grrrl \\ 3Y8OTSVISUJF

LWSRQOQGSW3L / Book ~ Riot grrrl Riot grrrl Filesize: 8.18 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is actually the very best work by any article writer. It usually does not price a lot of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Augustine Pfannerstill) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GOKP10TMWQNH / Kindle ~ Riot grrrl RIOT GRRRL To download Riot grrrl PDF, make sure you refer to the button under and download the document or gain access to other information which might be related to RIOT GRRRL book. Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 54. Chapters: Kill Rock Stars, Sleater-Kinney, Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna, Lucid Nation, Jessicka, Carrie Brownstein, Kids Love Lies, G. B. Jones, Sharon Cheslow, The Shondes, Jack O Jill, Not Bad for a Girl, Phranc, Bratmobile, Fih Column, Caroline Azar, Bikini Kill, Times Square, Jen Smith, Nomy Lamm, Huggy Bear, Karen Finley, Bidisha, Kaia Wilson, Emily's Sassy Lime, Mambo Taxi, The Yo-Yo Gang, Ladyfest, Bangs, Shopliing, Mecca Normal, Voodoo Queens, Sister George, Heavens to Betsy, Donna Dresch, Allison Wolfe, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, Tattle Tale, Sta-Prest, All Women Are Bitches, Excuse 17, Pink Champagne, Rise Above: The Tribe 8 Documentary, Juliana Luecking, Lungleg, Rizzo, Tammy Rae Carland, The Frumpies, Lisa Rose Apramian, List of Riot Grrl bands, 36-C, Girl Germs, Cold Cold Hearts, Frightwig, Yer So Sweet, Direction, Viva Knievel. Excerpt: Riot grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement based in Washington, DC, Olympia, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and the greater Pacific Northwest which existed in the early to mid-1990s, and it is oen associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Raising pure hell a general theory of articulation, the syntax of structural overdetermination, and the sound of social movements Peterson II, Victor Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 RAISING PURE HELL a general theory of Articulation, the syntax of structural overdetermination, and the sound of social movements by Victor Peterson II dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy King’s College, London 2018 Acknowledgements Meaning is made, value taken. -

From Vintage Collectors and Mixology Fans to Surf, Rockabilly and Punk Music Scenesters, the Escapist Vibes of the Tiki Scene Still Have a Strong Hold on Los Angeles

THE BEST TIKI DRINKS REVISITING GORDON PARKS’ CONTROVERSIAL PHOTO ESSAY TV’S FUTURE IS FEMALE ® AUGUST 2-8, 2019 / VOL. 41 / NO.37 / LAWEEKLY.COM From vintage collectors and mixology fans to surf, rockabilly and punk music scenesters, the escapist vibes of the tiki scene still have a strong hold on Los Angeles. And at Tiki Oasis in San Diego, everyone comes out to play. BY LINA LECARO 2 WEEKLY WEEKLY LA | A - , | | A WWW.LAWEEKLY.COM Welcome to the New Normal Experience life in the New Normal today. Present this page at any MedMen store to redeem this special offer. 10% off your purchase CA CA License A10-17-0000068-TEMP For one-time use only, redeemable until 06/30/19. Limit 1 per customer. Cannot be combined with any other offers. PAID ADVERTISEMENT 3 LA WEEKLY WEEKLY | A - , | | A THANK YOU, SENATOR DURAZO, FOR PUTTING PEOPLE BEFORE DRUG COMPANY PROFITS. WWW.LAWEEKLY.COM AARP thanks the members of the Senate Judiciary Committee for standing up for Californians and passing AB 824. This legislation would prohibit brand-name drug companies from paying generic manufacturers to delay the release of lower priced drugs. AARP strongly supports this important fi rst step towards ending the anti-competitive practices of big drug companies and lowering prescription drug prices for everyone. Too many people are struggling to make ends meet while the big drug companies continue to rake in billions. AARP encourages the entire Senate to pass AB 824, and put a stop to drug company price gouging. facebook.com/AARPCalifornia @AARPCA AARP.org/CA Paid For by AARP 4 L August 2-8, 2019 // Vol. -

Halperin David M Traub Valeri

GAY SHAME DAVID M. HALPERIN & VALERIE TRAUB I he University of Chicago Press C H I C A G 0 A N D L 0 N D 0 N david m. h alperin is theW. H. Auden Collegiate Professor of the History and Theory of Sexuality at the University of Michigan. He is the author of several books, including Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography (Oxford University Press, 1995) and, most re cently, What Do Gay Men Want? An Essay on Sex, Risk, and Subjectivity (University of Michi gan Press, 2007). valerie traub is professor ofEnglish andwomen's studies at the Uni versity of Michigan, where she chairs the Women's Studies Department. She is the author of Desire and Anxiety: Circulations of Sexuality in Shakesptanan Drama (Routledge, 1992) and The Renaissance of Ltsbianism in Early Modem England (Cambridge University Press, 2002). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2009 by The University of Chicago Al rights reserved. Published 2009 Printed in the United States of America 17 16 15 14 13 12 ii 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31437-2 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31438-9 (paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-31437-5 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-31438-3 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gay shame / [edited by] David M. Halperin and Valerie Traub. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31437-2 (cloth: alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-31437-5 (cloth: alk. -

Robert Quine Page 1 of 1 6/14/2004

Page 1 of 1 Robert Quine (Filed: 14/06/2004) Robert Quine, who has died aged 61, was acknowledged to be one of the most original and formidably talented guitarists in rock music; a founder member of American punk band The Voidoids, he later worked with Lou Reed, Tom Waits, Lloyd Cole and Brian Eno. At first glance, Bob Quine appeared an unlikely punk. A nephew of the philosopher W V Quine, he was a tax lawyer until his mid-thirties, by which time he was already nearly bald. Even at the height of his success, he took to the stage in a well-ironed shirt and black sports jacket, his only concession to attitude being the wearing of sunglasses. Equally out of keeping with punk's ethos was his command of his instrument, from which he produced an intense, aggressive, dissonant sound. Lou Reed acclaimed him as "a magnificent guitar player . an innovative tyro of the vintage beast". His skills are best preserved on Blank Generation, the album he recorded with Richard Hell in 1977. Having renounced the law, he was then working in a Greenwich Village bookshop with Hell and Tom Verlaine, both members of the proto-punk group Television. Hell, having fallen out with Verlaine and later with Johnny Thunders of The Heartbreakers, which he had gone on to join, put together a new band with Quine, Ivan Julian and Marc Bell (later of The Ramones) - The Voidoids. Quine coaxed suitably angry sounds from his Stratocaster to frame Hell's nihilistic yet purposeful lyrics, and the LP - especially its title track - became an underground success. -

Salad Days Mag7.Pdf

COVER The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle Pic Rigablood Below FightThePower Pic Rigablood WHAT’S HOT 6 Library 8 Walking in your shoes 12 Most Wanted 16 Kylesa BACKSTAGE 18 Don’t Sweat The Technique Editor In Chief/Founder - Andrea Rigano 20 Mi Bici Loca Art Director - Alexandra Romano, [email protected] 24 The Bloody Beetroots Advertising - Silvia Rapisarda, [email protected] Executive Producer - Mat The Cat 26 Vic Bondi English Editor - Rita Comi 30 Flashback Photographers - Luca Benedet, Peter Beste, Mattia Cabani, 36 Kids Of Grime Alvin Carrillo, Andrea Ghidini, Verena Stefanie Grotto, 42 Luca Contoli JAP, Lance 404, Augusto Lucati, Alex Luise, StreetBoxVideoLab, Federico Vezzoli, Ramon Zuliani 48 Dangers 52 Riding in Circle Illustrations - Fortuna Todisco, Rino Valente 56 Peter Beste Contributors - Milo Bandini, Alberto (Vela) Boggian, 62 Murder - West Coast Tour Maurice Bellotti/Poison For Souls, Luca Burato, Marco Capelli, Paola Dal Bosco, Giangiacomo De Stefano, Destrage, Flavio Ignelzi, Fra, Martina Lavarda, Andrea KNGL 72 Family Album Longo, Max Mbassadò, Andrea Mazzoli, Eros Pasi, Antonella Valente, Viola Von Hell, 76 The Restaurant - Bmx Alex ‘Wizo’, Marco ‘X-Man’ Xodo, Alberto Zannier, Giulio Repetto 80 El Da Sensei Stampa - Tipografia Nuova Jolly 82 Viola Von Hell - Sante Peccatrici Viale Industria 28 35030 Rubano (PD) 84 Destrage - Japanese Tour Report 86 Ardentees Salad Days Magazine è una rivista registrata presso il Tribunale di Vicenza, N. 1221 del 04/03/2010. 88 Highlights 90 Saints & Sinners Get in touch - www.saladdaysmag.com [email protected] 94 Stokin’ the Neighbours facebook.com/saladdaysmag 96 Shorter Faster Louder twitter.com/SaladDays_it L’editore è a disposizione di tutti gli interessati nel collaborare con testi immagini. -

Revendications Et Fiertés LGBTQ Chez Les Groupes De Queercore Louise Barrière

”Stonewall was a Riot” - Revendications et fiertés LGBTQ chez les groupes de Queercore Louise Barrière To cite this version: Louise Barrière. ”Stonewall was a Riot” - Revendications et fiertés LGBTQ chez les groupes de Queercore. Stonewall at 50 and beyond, Jun 2019, Créteil, France. hal-02560004 HAL Id: hal-02560004 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02560004 Submitted on 30 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. “Stonewall was a Riot” - Revendications et fiertés LGBTQ chez les groupes de Queercore L. Barrière (Université de Lorraine) Conférence « Stonewall at 50 and beyond » - UPEC – Juin 2019. Abstract Cette communication interrogent la manière dont les groupes du mouvement musical Queercore s'emparent et développent une imagerie de Stonewall, militante, revendicatrice et subculturelle. Le Queercore est en effet un mouvement qui nait aux États-Unis à la fin des années 1980, en marges à la fois des scènes punk et punk hardcore et des milieux LGBT, marqué par des groupes comme Pansy Division, Team Dresch, ou plus tard Limp Wrist,