Transporting Eating Architecture Lavash • Լաւաշ Rhode Island School of Design M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour Conductor and Guide: Norayr Daduryan

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour conductor and guide: Norayr Daduryan Price ~ $4,000 June 11, Thursday Departure. LAX flight to Armenia. June 12, Friday Arrival. Transport to hotel. June 13, Saturday 09:00 “Barev Yerevan” (Hello Yerevan): Walking tour- Republic Square, the fashionable Northern Avenue, Flower-man statue, Swan Lake, Opera House. 11:00 Statue of Hayk- The epic story of the birth of the Armenian nation 12:00 Garni temple. (77 A.D.) 14:00 Lunch at Sergey’s village house-restaurant. (included) 16:00 Geghard monastery complex and cave churches. (UNESCO World Heritage site.) June 14, Sunday 08:00-09:00 “Vernissage”: open-air market for antiques, Soviet-era artifacts, souvenirs, and more. th 11:00 Amberd castle on Mt. Aragats, 10 c. 13:00 “Armenian Letters” monument in Artashavan. 14:00 Hovhannavank monastery on the edge of Kasagh river gorge, (4th-13th cc.) Mr. Daduryan will retell the Biblical parable of the 10 virgins depicted on the church portal (1250 A.D.) 15:00 Van Ardi vineyard tour with a sunset dinner enjoying fine Italian food. (included) June 15, Monday 08:00 Tsaghkadzor mountain ski lift. th 12:00 Sevanavank monastery on Lake Sevan peninsula (9 century). Boat trip on Lake Sevan. (If weather permits.) 15:00 Lunch in Dilijan. Reimagined Armenian traditional food. (included) 16:00 Charming Dilijan town tour. 18:00 Haghartsin monastery, Dilijan. Mr. Daduryan will sing an acrostic hymn composed in the monastery in 1200’s. June 16, Tuesday 09:00 Equestrian statue of epic hero David of Sassoon. 09:30-11:30 Train- City of Gyumri- Orphanage visit. -

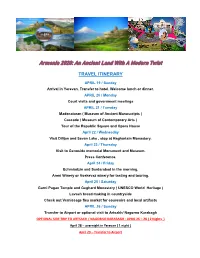

Armenia 2020: an Ancient Land with a Modern Twist

Armenia 2020: An Ancient Land With A Modern Twist TRAVEL ITINERARY APRIL 19 / Sunday Arrival in Yerevan. Transfer to hotel. Welcome lunch or dinner. APRIL 20 / Monday Court visits and government meetings APRIL 21 / Tuesday Madenataran ( Museum of Ancient Manuscripts ) Cascade ( Museum of Contemporary Arts ) Tour of the Republic Square and Opera House April 22 / Wednesday Visit Dilijan and Sevan Lake , stop at Haghartsin Monastery. April 23 / Thursday Visit to Genocide memorial Monument and Museum. Press Conference. April 24 / Friday Echmiadzin and Sardarabad in the morning. Areni Winery or Voskevaz winery for tasting and touring. April 25 / Saturday Garni Pagan Temple and Geghard Monastery ( UNESCO World Heritage ) Lavash bread making in countryside Check out Vernissage flea market for souvenirs and local artifacts APRIL 26 / Sunday Transfer to Airport or optional visit to Artsakh/ Nagorno Karabagh OPTIONAL SIDE TRIP TO ARTSAKH / NAGORNO KARABAGH : APRIL 26 – 28 ( 2 Nights ) April 28 – overnight in Yerevan ( 1 night ) April 29 – Transfer to Airport PRICES per person: Land Only! Double Occupancy Single Supplement MARRIOTT ( Deluxe room ) $1800 // $2300 MARRIOTT ( Superior ) $1900 // $2400 MARRIOTT ( Executive ) $2000 // $2650 ARTSAKH / NAGORNO-KARABAGH ( Optional side trip ) PRICE per person : HOTEL Double Occupancy Single Supplement VALLEX/ MARRIOTT ( Deluxe ) $400 // $100 VALLEX / MARRIOTT ( Superior ) $450 // $100 VALLEX / MARRIOTT ( Executive ) $500 // $100 EXTRA NIGHTS PER ROOM AT ARMENIA MARRIOTT DOUBLE SINGLE Deluxe $180 / $150 Superior $200 / $170 Executive $220 / $200 Included: Transfers , Half board meals ( daily breakfast & lunch, one dinner , one cultural event, English speaking guide on tour days and transportation as specified in itinerary. PAYMENT $500 non-refundable deposit due by November 30, 2019 by each participant. -

Armenian Tourist Attraction

Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... rediscover armenia guide armenia > tourism > rediscover armenia guide about cilicia | feedback | chat | © REDISCOVERING ARMENIA An Archaeological/Touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia Brady Kiesling July 1999 Yerevan This document is for the benefit of all persons interested in Armenia; no restriction is placed on duplication for personal or professional use. The author would appreciate acknowledgment of the source of any substantial quotations from this work. 1 von 71 13.01.2009 23:05 Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... REDISCOVERING ARMENIA Author’s Preface Sources and Methods Armenian Terms Useful for Getting Lost With Note on Monasteries (Vank) Bibliography EXPLORING ARAGATSOTN MARZ South from Ashtarak (Maps A, D) The South Slopes of Aragats (Map A) Climbing Mt. Aragats (Map A) North and West Around Aragats (Maps A, B) West/South from Talin (Map B) North from Ashtarak (Map A) EXPLORING ARARAT MARZ West of Yerevan (Maps C, D) South from Yerevan (Map C) To Ancient Dvin (Map C) Khor Virap and Artaxiasata (Map C Vedi and Eastward (Map C, inset) East from Yeraskh (Map C inset) St. Karapet Monastery* (Map C inset) EXPLORING ARMAVIR MARZ Echmiatsin and Environs (Map D) The Northeast Corner (Map D) Metsamor and Environs (Map D) Sardarapat and Ancient Armavir (Map D) Southwestern Armavir (advance permission -

Global Village Program Handbook 2012 Global Village Handbook

Global Village Program Handbook 2012 Global Village Handbook Published by: Habitat for Humanity Armenia Supported by: 2012 Habitat for Humanity Armenia, All rights reserved Global Village Program Handbook 2012 Table of Welcome from Habitat for Humanity Armenia Contents WELCOME TO ARMENIA Social Traditions, gestures, clothing, and culture 7 Dear Global Village team members, Traditional food 8 Language 8 Many thanks for your interest and Construction terms 9 willingness to join Habitat for Packing list 10 Humanity Armenia in building HFH ARMENIA NATIONAL PROGRAM simple, decent, affordable and The housing need in Armenia 11 Needs around the country and HFH's response 11 healthy homes in Armenia. You Repair & Renovation of homes in Spitak 12 will be a great help in this ancient Housing Microfinance Project in Tavush, Gegharkunik and Lori 13 country and for sure will have lots Housing Renovation Project in Nor Kharberd community 14 of interesting experiences while Partner Families Profiles/ Selection Criteria 15 working with homeowners and GV PROGRAM visiting different parts of Armenia. Global Village Program Construction Plans for the year 17 Living conditions of the volunteers 17 Our staff and volunteers are here to Construction site 18 assist you with any questions you Transportation 18 R&R options 18 may have. Do not hesitate to contact Health and safety on site 20 anyone whenever you have Health and safety off site 24 Type of volunteer work 25 questions. This handbook is for Actual Family Interactions/Community/Special Events 25 your attention to answer questions GV POLICIES 26 Gift Giving Policy 26 that you may have before landing HFH Armenia GV Emergency Management Plan 2012 27 in the country and during your USEFUL INFORMATION Habitat for Humanity service trip Arrival in Armenia (airport, visa) 28 to Armenia. -

Magnificent Armenia 6 Days / 5 Nights Day 1: Arrival in Yerevan Arrival in Yerevan

Magnificent Armenia 6 days / 5 nights Day 1: Arrival in Yerevan Arrival in Yerevan. Transfer to the selected hotel. Overnight in Yerevan. Day 2: Yerevan City tour Breakfast at the hotel. City tour in Yerevan will start with the panoramic view of the city and acquaintance with the Center of the city, Republic Square, the sightseeing of Opera and Ballet building, the Parliament and Residency of the President of Armenia, State University, Mother Armenia Monument, Sports & Concert Complex. A visit to Tsitsernakaberd - a Monument to the Armenian Genocide Victims, as well as the Genocide Victims’ Museum, commemorating the 1.5 million Armenians who perished during the first Genocide of the 20th century in the Western Armenia and in the territory of Ottoman Empire. Visit Cascade complex, which is considered the modern art center of Yerevan. Cascade is home to Cafesjan modern art museum. This place becomes even more charming in the evenings, when it is full of people, both locals and tourists from all over the world, enjoying the magic and the warmth of the capital. You will enjoy spending time in one of the cosy cafes surrounded by beautiful sculptures. A visit to one of the biggest and oldest mosques in Caucasus “Blue mosque”, which is situated in the heart of Yerevan city. Overnight in Yerevan. Day 3: Yerevan - Lake Sevan - “Ar men ian S w itzerlan d ” Dili jan - Yerevan Breakfast at the hotel. Drive to Lake Sevan, one of the wonders in Armenia. This blue lake is one of the greatest high mountainous freshwater lakes of Eurasia. -

A Thesis Submitted to the Central European University, Department

A thesis submitted to the Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy of Central European University in part fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Science Protected areas and tourism development: Case of the Dilijan National Park, Armenia CEU eTD Collection Anahit AGHABABYAN July, 2009 Budapest 1 Notes on copyright and the ownership of intellectual property rights: (1) Copyright in text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European University Library. Details may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the Author. (2) The ownership of any intellectual property rights which may be described in this thesis is vested in the Central European University, subject to any prior agreement to the contrary, and may not be made available for use by third parties without the written permission of the University, which will prescribe the terms and conditions of any such agreement. (3) For bibliographic and reference purposes this thesis should be referred to as: Aghababyan, A. 2009. Protected areas and tourism development: Case of the Dilijan National Park, Armenia. Master of Science thesis, Central European University, Budapest. Further information on the conditions under which disclosures and exploitation may take place is available from the Head of the Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy, Central European University. -

2018–2019 Annual Report

2018–2019 ANNUAL REPORT SUSTAIN EMPOWER TEACH 1 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT 25 YEARS OF SUSTAINING, EMPOWERING, AND TEACHING… From the Desk of the Executive Director As always, we invite you to include ATP in your By Jeanmarie Papelian itinerary when you visit Armenia. We love to show our work, and you can even plant a tree with us! If I’m pleased to share ATP’s annual report with you. your schedule brings you to Yerevan in October, As you’ll see in these pages, we’re continuing to fulfill be sure to come to the conference we’re planning our mission of using trees to help Armenians improve with the American University’s Acopian Center their standard of living. Last year, our four nurseries for the Environment. Forest Summit: Global produced over 250,000 trees which we planted in Action and Armenia will bring together experts to sites all over Armenia and Artsakh. The total number discuss Armenia’s environmental challenges and of trees we’ve planted since 1994 exceeds 5.7 million, opportunities. The conference will include field visits and we’re on track to reach six million this year. to both state forests and ATP’s nurseries. ATP’s work is about so much more than planting 2019 marks ATP’s 25th anniversary, and soon we’ll trees. We sustain Armenia’s environment by ensuring kick of a yearlong celebration. ATP’s success is a high survival rate of the trees we plant while the result of dedicated and generous support from enriching the soil, water, air quality and harvests. -

THE STUDY on LANDSLIDE DISASTER MANAGEMENT in the REPUBLIC of ARMENIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME-V February 2006 KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., L

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY MINISTRY OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT, THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA THE STUDY ON LANDSLIDE DISASTER MANAGEMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME-V SECTORAL REPORT – 1 - PRESENT CONDITIONS - February 2006 KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. THE STUDY ON LANDSLIDE DISASTER MANAGEMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME-V SECTORAL REPORT-1 - PRESENT CONDITIONS - Table of Contents Page CHAPTER 1 NATURAL CONDITIONS ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 Topography ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Geology ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.3 Climate ................................................................................................................................ 6 CHAPTER-2 LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM........................................................... 8 2.1 Legal System................................................................................................................................ 8 2.2 Policy, Budget, and Economy ...................................................................................................... 15 CHAPTER-3 COMMUNITY STRUCTURE ................................................................................ 18 3.1 Purpose and Policy Of Study....................................................................................................... -

Animal Representation in the Medieval Armenian Art

Animal representation in the medieval Armenian art N. Manaseryan & L. Mirzoyan *Institute of Zoology of Armenian National Academy of Sciences **Université Marc Bloch, Institut d’Histoire et Archéologie de l’Orient ancien Medieval Armenian animalistic art belongs to the brightest pages of the world cultural heritage. Animal images are presented in any type of artwork from everyday use objects to the medieval masterpieces. Ceramic objects mostly decorated by bird images were playing substantial role in the medieval art (fig. 1a & 1b). Beautiful animalistic images are present on the significant amount of the applied art objects made of metal (fig. 2). Animals were common motives also in Medieval Armenian embroideries (fig. 3). In the famous Armenian Medieval manuscripts animals are presented both to introduce the meaning of the text and to decorate the manuscript (fig. 4a & 4b). Medieval Armenian art is very rich of animal representations on the inner and outer decorations of the monasteries and churches (fig. 5a; 5b; 5c; 5d; 5e & 5f). Nobel families created their family emblems with animal images as a sign of their power and strength (fig. 6a & 6b). Tombstones of those times were splendidly decorated too with professional scenes including animals depending on the occupation of the deceased (fig. 7a; 7b & 7c). As we can see in the above presented images, various animals served as an inspiration source for medieval masters. Wild animals like reptiles, birds, big carnivores (lion, leopard), wild artiodactyls (bezoar goat, muflon) etc. are present on the art objects. Domestic animals as bull, sheep, goat, horse, dog, etc. are common motives too. -

Tour Itinerary

GEEO ITINERARY ARMENIA and GEORGIA 7/15/2022– Summer Day 1: Yerevan Arrive at any time. Arrive at any time today, but we highly recommend coming in a day early as there is a lot to see in Yerevan. Our program will begin tonight in Yerevan, and we typically have a group meeting at the hotel around 6:00 p.m. Upon arrival at the hotel, please check the notice board for information about the group meeting. During the group meeting, the leader will outline the trip itinerary and answer questions. Day 2: Yerevan (B) Drive to Echmiadzin and visit the cathedral. Later, enjoy a city tour of Yerevan, followed by a visit to the Genocide Memorial. Take some free time to explore the city of Yerevan. Today we begin by driving to Echmiadzin, Armenia's ancient capital city. We will stop at its famous cathedral, one of the world's first Christian churches (built in 301 AD). Learn about the cathedral’s history and change in architectural style after it was damaged in the late 400's. Afterward, we drive back toward Yerevan. We will visit the Armenian Genocide Memorial and Museum to better understand and reflect on the first genocide of the 20th century. Commemorating the massacre of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire from 1915 to 1922, the Museum explains the story of this horrific historical event. Over 1.5 million Armenians were systematically killed by the governing Ottoman Empire and then the Republic of Turkey after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Even today, a century later, Armenia has a population of only 3 million people. -

Armenia a Fresh View of a Forgotten Land Monday 27 April to Tuesday 5 May 2015

ARMENIA A FRESH VIEW OF A FORGOTTEN LAND MONDAY 27 APRIL TO TUESDAY 5 MAY 2015 CLARE FORD-WILLE AND PETER SHAHBENDARIAN Art Historian Clare Ford-Wille and her husband, Armenian expert Peter Shahbendarian, lead a deeply respectful and thorough journey through a wealth of sacred sites uncovering the many rich layers of Armenia’s ancient and exotic heritage. A small country uncomfortably balanced between East and West, and fought over by empires -Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Seljuks, Mongols, Russians and Ottomans- Armenia, nevertheless, tenaciously protected and preserved its identity as the first country to establish Christianity as a state religion in 301 AD, in the earliest years of Christian hegemony. Though they contributed enormously to the infrastructure and finances of the mighty Ottoman Empire, Armenians were persecuted. Eventually and eventfully, an independent Republic emerged in 1991. Land-locked on a central plateau 5,500 feet above sea-level, its regal landscape of mountains and lakes is spectacular. Clare and Peter will skilfully lead the way in and out of ancient towns and villages with poignant visits to still-vibrant monastic communities protected by World Heritage designation. Armenia’s magnificent early Hellenistic temple, monastic architecture, rock-hewn churches and stone crosses, together with priceless manuscripts and works of art, will present surprises and wonders to behold. COST £3355 members, £3415 non-members, £400 single room supplement, £300 deposit, includes flights London-Yerevan-London (with short stopovers), eight nights accommodation, all breakfasts, all lunches, all dinners with wine, tuition from Clare Ford- Wille and Peter Shahbendarian, the services of a local tour manager, all entrance fees, all private minibus travel during the tour, all gratuities, VAT. -

Specially Protected Nature Areas of Armenia

MINISTRY OF NATURE PROTECTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA NAZIK KHANJYAN SPECIALLY PROTECTED NATURE AREAS OF ARMENIA YEREVAN 2004 ……..NAZIK KHANJYAN, Specially Protected Nature Areas of Armenia, Yerevan, “Tigran Mets”, 2004, 54 pages, 79 photos. This publication is the English translation of the second amended edition of “Specially protected areas of Armenia” (2004, in Armenian). It summarizes many years of research and fieldwork by the author as well as numerous scientific publications on the subject. The publication is devoted to the fulfillment of the commitments of the Republic of Armenia under the UN Convention on Biodiversity and the 45th anniversary of establishment of specially protected areas in Armenia. The publication is intended for teachers, students, nature protection and nature use professionals and readers at large. Editor - Samvel Baloyan, Ph.D., Professor, Corresponding Member of the Academy of Ecology of the Russian Federation. Photos by Nazik Khanjyan, Vrezh Manakyan, Robert Galstyan, Martin Adamyan, Edward Martirosyan, Hrach Ghazaryan, Aghasi Karagezyan, Norik Badalyan Design by Edward Martirosyan Editor of the English translation Siranush Galstyan ISBN @ N.Khanjyan, 2004 The publication has been prepared under the “National Capacity Self-Assessment for Global Environmental Management” Project, UNDP/GEF/ARM/02/G31/A/1G/99 2 INTRODUCTION The Republic of Armenia is located in the north-eastern part of the Armenian Plateau and occupies 29,740 km2 at altitudes ranging from 375 to 4095 meters above sea level. Armenia is a mountainous country with a characteristic ragged relief and a wide variety of climatic conditions and soils. In addition, Armenia is located on the intersection of two different physical-geographic areas, particularly, various botanical-geographic regions, such as the Caucasian mesophilous and Armenian-Iranian xerophilous ones, where natural speciation is active.