The Zhamatun of Horomos: the Shaping of an Unprecedented Type of Fore-Church Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia, Armenia & Azerbaijan

Land Program Rate: $6,195 (per person based on double occupancy) Single Supplement: $1,095 Included: All accommodation, hotel taxes • Meals per itinerary (B=breakfast, L=lunch, D=dinner) • Arrival/departure transfers for pas- sengers arriving/departing on scheduled start/ end days • All land transportation per itinerary including private motor coach throughout the itinerary • Internal airfare between Baku and Tbilisi • Study leader and pre-departure education materials • Special cultural events and extensive sightseeing, includ- ing entrance fees • Welcome and farewell dinners • Services of a tour manager throughout the land program • Gratuities to tour manager, guides and drivers • Comprehensive pre-departure packet Not Included: Travel insurance • Round trip airfare between Baku/Yerevan and USA. Our tour operator MIR Corporation can assist with reservations. • Passport and visa fees • Meals not specified as included in the itinerary • Personal items such as telephone calls, alcohol, laun- dry, excess baggage fees Air Arrangements: Program rates do not include international airfare from/to USA. Because there are a number of flight options available, there is no group flight for this program. Informa- tion on a recommended flight itinerary will be sent by our tour operator upon confirmation. What to Expect: This trip is moderately active due to the substantial distances covered and Club of California The Commonwealth St 555 Post CA 94102 San Francisco, the extensive walking and stair climbing required; parts of the tour will not always be wheelchair - accessible. To reap the full rewards of this adventure, travelers must be able to walk at least a mile a day (with or without the assistance of a cane) and stand for an extended period of time during walking tours and museum visits. -

Documentary and Artistic Perspectives on the Armenian Genocide in the Golden Apricot Film Festival

DOCUMEntary AND Artistic PERSPECTIVES ON THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE IN THE GOLDEN APRICOT FILM FEstival Reviewed by Serafim Seppälä University of Eastern Finland Stony Paths. Dir. Arnaud Khayadjanian. France 2016, 60 min. The Other Side of Home. Dir. Naré Mkrtchyan. USA/Armenia/Turkey 2016, 40 min Journey in Anatolia. Dir. Bernard Mangiante. France 2016, 60 min. Gavur Neighbourhood. Dir. Yusuf Kenan Beysülen. Turkey 2016, 95 min. Geographies. Dir.Chaghig Arzoumanian. Lebanon 2015, 72 min. Children of Vank. Dir. Nezahat Gündoğan. Turkey 2016, 70 min. Who Killed the Armenians? Dir. Mohamed Hanafy Nasr. Egypt 2015, 73 min. The famous Golden Apricot film festival in Yerevan has become, among its other aims, a remarkable forum for documentary and artistic films on the Armenian genocide and its cul- tural legacies. In recent years, the emphasis of the genocide-related documentary films has shifted from historical presentations of the actual events to the cases of lost Armenians and rediscoveries of Armenian identities inside Turkey, in addition to the stories of Western Armenians tracing the whereabouts of their forefathers. The centennial output In the centennial year of 2015, the genocide was a special theme in Golden Apricot, anda big number of old genocide-related films were shown in retrospective replays. As was to be expected, the centennial witnessed also a burst of new documentaries and a few more artistic enterprises. The new films included documentaries on Armenians looking for their roots in Western Armenia, such as Adrineh Gregorian’s Back to Gürün (Armenia 2015, 64 min) and Eric Nazarian’s Bolis (2011, 19 min), or Istanbul Armenians returning to their an- cestral lands for the summer, as was the case in Armen Khachatryan’s touching Return or we exist 2 (52 min). -

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour Conductor and Guide: Norayr Daduryan

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour conductor and guide: Norayr Daduryan Price ~ $4,000 June 11, Thursday Departure. LAX flight to Armenia. June 12, Friday Arrival. Transport to hotel. June 13, Saturday 09:00 “Barev Yerevan” (Hello Yerevan): Walking tour- Republic Square, the fashionable Northern Avenue, Flower-man statue, Swan Lake, Opera House. 11:00 Statue of Hayk- The epic story of the birth of the Armenian nation 12:00 Garni temple. (77 A.D.) 14:00 Lunch at Sergey’s village house-restaurant. (included) 16:00 Geghard monastery complex and cave churches. (UNESCO World Heritage site.) June 14, Sunday 08:00-09:00 “Vernissage”: open-air market for antiques, Soviet-era artifacts, souvenirs, and more. th 11:00 Amberd castle on Mt. Aragats, 10 c. 13:00 “Armenian Letters” monument in Artashavan. 14:00 Hovhannavank monastery on the edge of Kasagh river gorge, (4th-13th cc.) Mr. Daduryan will retell the Biblical parable of the 10 virgins depicted on the church portal (1250 A.D.) 15:00 Van Ardi vineyard tour with a sunset dinner enjoying fine Italian food. (included) June 15, Monday 08:00 Tsaghkadzor mountain ski lift. th 12:00 Sevanavank monastery on Lake Sevan peninsula (9 century). Boat trip on Lake Sevan. (If weather permits.) 15:00 Lunch in Dilijan. Reimagined Armenian traditional food. (included) 16:00 Charming Dilijan town tour. 18:00 Haghartsin monastery, Dilijan. Mr. Daduryan will sing an acrostic hymn composed in the monastery in 1200’s. June 16, Tuesday 09:00 Equestrian statue of epic hero David of Sassoon. 09:30-11:30 Train- City of Gyumri- Orphanage visit. -

Armenia 2020: an Ancient Land with a Modern Twist

Armenia 2020: An Ancient Land With A Modern Twist TRAVEL ITINERARY APRIL 19 / Sunday Arrival in Yerevan. Transfer to hotel. Welcome lunch or dinner. APRIL 20 / Monday Court visits and government meetings APRIL 21 / Tuesday Madenataran ( Museum of Ancient Manuscripts ) Cascade ( Museum of Contemporary Arts ) Tour of the Republic Square and Opera House April 22 / Wednesday Visit Dilijan and Sevan Lake , stop at Haghartsin Monastery. April 23 / Thursday Visit to Genocide memorial Monument and Museum. Press Conference. April 24 / Friday Echmiadzin and Sardarabad in the morning. Areni Winery or Voskevaz winery for tasting and touring. April 25 / Saturday Garni Pagan Temple and Geghard Monastery ( UNESCO World Heritage ) Lavash bread making in countryside Check out Vernissage flea market for souvenirs and local artifacts APRIL 26 / Sunday Transfer to Airport or optional visit to Artsakh/ Nagorno Karabagh OPTIONAL SIDE TRIP TO ARTSAKH / NAGORNO KARABAGH : APRIL 26 – 28 ( 2 Nights ) April 28 – overnight in Yerevan ( 1 night ) April 29 – Transfer to Airport PRICES per person: Land Only! Double Occupancy Single Supplement MARRIOTT ( Deluxe room ) $1800 // $2300 MARRIOTT ( Superior ) $1900 // $2400 MARRIOTT ( Executive ) $2000 // $2650 ARTSAKH / NAGORNO-KARABAGH ( Optional side trip ) PRICE per person : HOTEL Double Occupancy Single Supplement VALLEX/ MARRIOTT ( Deluxe ) $400 // $100 VALLEX / MARRIOTT ( Superior ) $450 // $100 VALLEX / MARRIOTT ( Executive ) $500 // $100 EXTRA NIGHTS PER ROOM AT ARMENIA MARRIOTT DOUBLE SINGLE Deluxe $180 / $150 Superior $200 / $170 Executive $220 / $200 Included: Transfers , Half board meals ( daily breakfast & lunch, one dinner , one cultural event, English speaking guide on tour days and transportation as specified in itinerary. PAYMENT $500 non-refundable deposit due by November 30, 2019 by each participant. -

L'arte Armena. Storia Critica E Nuove Prospettive Studies in Armenian

e-ISSN 2610-9433 THE ARMENIAN ART ARMENIAN THE Eurasiatica ISSN 2610-8879 Quaderni di studi su Balcani, Anatolia, Iran, Caucaso e Asia Centrale 16 — L’arte armena. Storia critica RUFFILLI, SPAMPINATO RUFFILLI, FERRARI, RICCIONI, e nuove prospettive Studies in Armenian and Eastern Christian Art 2020 a cura di Edizioni Aldo Ferrari, Stefano Riccioni, Ca’Foscari Marco Ruffilli, Beatrice Spampinato L’arte armena. Storia critica e nuove prospettive Eurasiatica Serie diretta da Aldo Ferrari, Stefano Riccioni 16 Eurasiatica Quaderni di studi su Balcani, Anatolia, Iran, Caucaso e Asia Centrale Direzione scientifica Aldo Ferrari (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Stefano Riccioni (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Comitato scientifico Michele Bacci (Universität Freiburg, Schweiz) Giampiero Bellingeri (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Levon Chookaszian (Yerevan State University, Armenia) Patrick Donabédian (Université d’Aix-Marseille, CNRS UMR 7298, France) Valeria Fiorani Piacentini (Università Cattolica del Sa- cro Cuore, Milano, Italia) Ivan Foletti (Masarikova Univerzita, Brno, Česká republika) Gianfranco Giraudo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Annette Hoffmann (Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, Deutschland) Christina Maranci (Tuft University, Medford, MA, USA) Aleksander Nau- mow (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Antonio Panaino (Alma Mater Studiorum, Università di Bologna, Italia) Antonio Rigo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Adriano Rossi (Università degli Studi di Napoli «L’Orientale», Italia) -

Georgia Armenia Azerbaijan 4

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 317 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travell ers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well- travell ed team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to postal submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/privacy. Stefaniuk, Farid Subhanverdiyev, Valeria OUR READERS Many thanks to the travellers who used Superno Falco, Laurel Sutherland, Andreas the last edition and wrote to us with Sveen Bjørnstad, Trevor Sze, Ann Tulloh, helpful hints, useful advice and interest- Gerbert Van Loenen, Martin Van Der Brugge, ing anecdotes: Robert Van Voorden, Wouter Van Vliet, Michael Weilguni, Arlo Werkhoven, Barbara Grzegorz, Julian, Wojciech, Ashley Adrian, Yoshida, Ian Young, Anne Zouridakis. Asli Akarsakarya, Simone -

50146-001: Distribution Network Rehabilitation, Efficiency

Initial E nvironmental E xamination Project Number: 50146-001 April 2017 Distribution Network R ehabilitation, E fficiency Improvement, and Augmentation (R epublic of Armenia) Prepared by Tetra Tech E S , Inc. for the Asian Development Bank This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Y our attention is directed to the “Terms of Use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Armenia: ENA-Modernisation of Distribution Network Initial Environmental Examination: Draft Final Report Prepared by April 2017 1 ADB/EBRD Armenia: ENA - Modernisation of Distribution Network Initial Environmental Examination Draft Final Report April 2017 Prepared by Tetra Tech ES, Inc. 1320 N Courthouse Rd, Suite 600 | Arlington, VA 22201, United States Tel +1 703 387 2100 | Fax +1 703 243 0953 www.tetratech.com Prepared by Tetra Tech ES, Inc 2 ENA - Modernisation of Distribution Network Initial Environmental Examination Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................ 3 Abbreviations and Acronyms ........................................................................................... -

Eduard L. Danielyan Progressive British Figures' Appreciation of Armenia's Civilizational Significance Versus the Falsified

INSTITUTE OF HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA EDUARD L. DANIELYAN PROGRESSIVE BRITISH FIGURES’ APPRECIATION OF ARMENIA’S CIVILIZATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE VERSUS THE FALSIFIED “ANCIENT TURKEY” EXHIBIT IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM YEREVAN 2013 1 PUBLISHED WITH THE APPROVAL OF THE SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL OF THE INSTITUTE OF HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA This work was supported by State Committee of Science MES RA, in frame of the research project № 11-6a634 “Falsification of basic questions of the history of Armenia in the Turkish-Azerbaijani historiogrpahy”. Reviewer A.A.Melkonyan, Doctor of History, corresponding member of the NAS RA Edited by Dr. John W. Mason, Pauline H. Mason, M.A. Eduard L. Danielyan Progressive British Figures’ Appreciation of Armenia’s Civilizational Significance Versus the Falsified “Ancient Turkey” Exhibit in the British Museum This work presents a cultural-spiritual perception of Armenia by famous British people as the country of Paradise, Noah’s Ark on Mt. Ararat-Masis and the cradle of civilization. Special attention is paid in the book to the fact that modern British enlightened figures call the UK government to recognize the Armenian Genocide, but this question has been politicized and subjected to the interests of UK-Turkey relations, thus being pushed into the genocide denial deadlock. The fact of sheltering and showing the Turkish falsified “interpretations” of the archaeological artifacts from ancient sites of the Armenian Highland and Asia Minor in the British Museum’s “Room 54” exhibit wrongly entitled “Ancient Turkey” is an example of how the genocide denial policy of Turkey pollutes the Britain’s historical-cultural treasury and distorts rational minds and inquisitiveness of many visitors from different countries of the world.The author shows that Turkish falsifications of history have been widely criticized in historiography. -

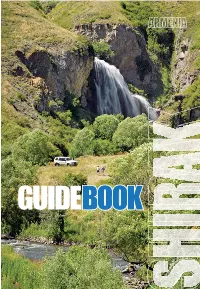

Shirak Guidebook

Wuthering Heights of Shirak -the Land of Steppe and Sky YYerevanerevan 22013013 1 Facts About Shirak FOREWORD Mix up the vast open spaces of the Shirak steppe, the wuthering wind that sweeps through its heights, the snowcapped tops of Mt. Aragats and the dramatic gorges and sparkling lakes of Akhurian River. Sprinkle in the white sheep fl ocks and the cry of an eagle. Add churches, mysterious Urartian ruins, abundant wildlife and unique architecture. Th en top it all off with a turbulent history, Gyumri’s joi de vivre and Gurdjieff ’s mystical teaching, revealing a truly magnifi cent region fi lled with experi- ences to last you a lifetime. However, don’t be deceived that merely seeing all these highlights will give you a complete picture of what Shirak really is. Dig deeper and you’ll be surprised to fi nd that your fondest memories will most likely lie with the locals themselves. You’ll eas- ily be touched by these proud, witt y, and legendarily hospitable people, even if you cannot speak their language. Only when you meet its remarkable people will you understand this land and its powerful energy which emanates from their sculptures, paintings, music and poetry. Visiting the province takes creativity and imagination, as the tourist industry is at best ‘nascent’. A great deal of the current tourist fl ow consists of Diasporan Armenians seeking the opportunity to make personal contributions to their historic homeland, along with a few scatt ered independent travelers. Although there are some rural “rest- places” and picnic areas, they cater mainly to locals who want to unwind with hearty feasts and family chats, thus rarely providing any activities. -

AN ARMENIAN MEDITERRANEAN Words and Worlds in Motion CHAPTER 5

EDITED BY KATHRYN BABAYAN AND MICHAEL PIFER AN ARMENIAN MEDITERRANEAN Words and Worlds in Motion CHAPTER 5 From “Autonomous” to “Interactive” Histories: World History’s Challenge to Armenian Studies Sebouh David Aslanian In recent decades, world historians have moved away from more conventional studies of nations and national states to examine the role of transregional networks in facilitating hemispheric interactions and connectedness between This chapter was mostly written in the summer of 2009 and 2010 and episodically revised over the past few years. Earlier iterations were presented at Armenian Studies workshops at the University of California, Los Angeles in 2009, and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor in 2012 and 2015. I am grateful to the conveners of the workshops for the invitation and feedback. I would also like to thank especially Houri Berberian, Jirair Libaridian, David Myers, Stephen H. Rapp, Khachig Tölölyan, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Kathryn Babayan, Richard Antaramian, Giusto Traina, and Marc Mamigonian for their generous comments. As usual, I alone am responsible for any shortcomings. S. D. Aslanian (*) University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA © The Author(s) 2018 81 K. Babayan, M. Pifer (eds.), An Armenian Mediterranean, Mediterranean Perspectives, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72865-0_5 82 S. D. ASLANIAN cultures and regions.1 This shift from what may be called the optic of the nation(-state) to a global optic has enabled historians to examine large- scale historical processes -

Years in Armenia

1O Years of Independence and Transition in Armenia National Human Development Report Armenia 2OO1 Team of Authors National Project Director Zorab Mnatsakanyan National Project Coordinator-Consultant Nune Yeghiazaryan Chapter 1 Mkrtich Zardaryan, PhD (History) Aram Harutunyan Khachatur Bezirchyan, PhD (Biology) Avetik Ishkhanyan, PhD (Geology) Boris Navasardyan Ashot Zalinyan, PhD (Economics) Sos Gimishyan Edward Ordyan, Doctor of Science (Economics) Chapter 2 Ara Karyan, PhD (Economics) Stepan Mantarlyan, PhD (Economics) Bagrat Tunyan, PhD (Economics) Narine Sahakyan, PhD (Economics) Chapter 3 Gyulnara Hovhanessyan, PhD (Economics) Anahit Sargsyan, PhD (Economics) "Spiritual Armenia" NGO, Anahit Harutunyan, PhD (Philology) Chapter 4 Viktoria Ter-Nikoghosyan, PhD (Biophysics) Aghavni Karakhanyan Economic Research Institute of the RA Ministry of Finance & Economy, Armenak Darbinyan, PhD (Economics) Nune Yeghiazaryan Hrach Galstyan, PhD (Biology) Authors of Boxes Information System of St. Echmiadzin Sergey Vardanyan, "Spiritual Armenia" NGO Gagik Gyurjyan, Head of RA Department of Preservation of Historical and Cultural Monuments Gevorg Poghosyan, Armenian Sociological Association Bagrat Sahakyan Yerevan Press Club "Logika", Independent Research Center on Business and Finance Arevik Petrosian, Aharon Mkrtchian, Public Sector Reform Commission, Working Group on Civil Service Reforms Armen Khudaverdian, Secretary of Public Sector Reform Commission "Orran" Benevolent NGO IOM/Armenia office Karine Danielian, Association "For Sustainable Human -

Armenia, Republic of | Grove

Grove Art Online Armenia, Republic of [Hayasdan; Hayq; anc. Pers. Armina] Lucy Der Manuelian, Armen Zarian, Vrej Nersessian, Nonna S. Stepanyan, Murray L. Eiland and Dickran Kouymjian https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T004089 Published online: 2003 updated bibliography, 26 May 2010 Country in the southern part of the Transcaucasian region; its capital is Erevan. Present-day Armenia is bounded by Georgia to the north, Iran to the south-east, Azerbaijan to the east and Turkey to the west. From 1920 to 1991 Armenia was a Soviet Socialist Republic within the USSR, but historically its land encompassed a much greater area including parts of all present-day bordering countries (see fig.). At its greatest extent it occupied the plateau covering most of what is now central and eastern Turkey (c. 300,000 sq. km) bounded on the north by the Pontic Range and on the south by the Taurus and Kurdistan mountains. During the 11th century another Armenian state was formed to the west of Historic Armenia on the Cilician plain in south-east Asia Minor, bounded by the Taurus Mountains on the west and the Amanus (Nur) Mountains on the east. Its strategic location between East and West made Historic or Greater Armenia an important country to control, and for centuries it was a battlefield in the struggle for power between surrounding empires. Periods of domination and division have alternated with centuries of independence, during which the country was divided into one or more kingdoms. Page 1 of 47 PRINTED FROM Oxford Art Online. © Oxford University Press, 2019.