Eye-Color Changes in Barrow's Goldeneye and Common

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elemental Nest & Fold

elemental nest & fold 30x72 adjustable height MODEL #: NL3072_ _ _ _ _ _EJ DIMENSIONS + FREIGHT BUILD PART NUMBER MODEL DESCRIPTION LEG TYPE D" W" H" F.C. CUBE WT. NL ————3 072 —711 —812 —913 —10 — — — ——EJ Rectangle models or Color Pick Edge N8 Choose Pick Laminate Pick Leg Color Pick Leg Style NL3072_ _ _ _ _ _ _EJ 30x72 Nest & Fold Adjustable Height 30 72 29-40 70 1.6 59 Color MODEL Fixed-height with caster (EF) Adjustable-height with caster (EJ) C olor OVERVIEW Elemental Nest & Fold tables have 5 frame colors,ors, with matching colored casters standard.The uniqueque colored legs are adjustable in height from 29” too 40” high. The tables’ work surface flips upwardss fforor convenient nesting. MATERIALS The 1 1/4” thick WORK SURFACE consists of a 4545 lb density particle board core with a 0.030” highh pressure laminated surface and a 0.020” melaminemine backer sheet. The edge of the tabletop featureses your choice of a 3/8” bumper t-mold or 4mm t-mold,mold, which is then fastened to the underside of the workwork surface every 6 to 8 inches to assure a long lastinging fit.fit. Mounted under the work surface is a 11 gauge steelsteel STIFFENER for reinforcement. The Elemental LEG SETS are constructed of 16-gauge steel with a durable powdercoat paintt finish in one of five colors. The pull-bar and mountingunting beam are also constructed of 16-gauge steel. 72.0072.000 Color matched dual-wheel 3” casters standard on Nest & Fold tables. -

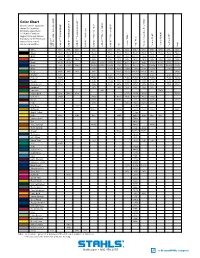

Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® Equivalent Shown

™ ™ II ® Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® equivalent shown. Due to printing limitations, colors shown 5807 Reflective ® ® ™ ® ® and Pantone numbers ® ™ suggested may vary from ac- ECONOPRINT GORILLA GRIP Fashion-REFLECT Reflective Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP ® ® ® ® ® ® ® tual colors. For the truest color ® representation, request Scotchlite our material swatches. ™ CAD-CUT 3M CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT Felt Perma-TWILL Poly-TWILL Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP Vinyl Pressure Sensitive Poly-TWILL Sensitive Pressure CAD-CUT White White White White White White White White White* White White White White White Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black* Black Black Black Black Black Gold 1235C 136C 137C 137C 123U 715C 1375C* 715C 137C 137C 116U Red 200C 200C 703C 186C 186C 201C 201C 201C* 201C 186C 186C 186C 200C Royal 295M 294M 7686C 2747C 7686C 280C 294C 294C* 294C 7686C 2758C 7686C 654C Navy 296C 2965C 7546C 5395M 5255C 5395M 276C 532C 532C* 532C 5395M 5255C 5395M 5395C Cool Gray Warm Gray Gray 7U 7539C 7539C 415U 7538C 7538C* 7538C 7539C 7539C 2C Kelly 3415C 341C 340C 349C 7733C 7733C 7733C* 7733C 349C 3415C Orange 179C 1595U 172C 172C 7597C 7597C 7597C* 7597C 172C 172C 173C Maroon 7645C 7645C 7645C Black 5C 7645C 7645C* 7645C 7645C 7645C 7449C Purple 2766C 7671C 7671C 669C 7680C 7680C* 7680C 7671C 7671C 2758U Dark Green 553C 553C 553C 447C 567C 567C* 567C 553C 553C 553C Cardinal 201C 188C 195C 195C* 195C 201C Emerald 348 7727C Vegas Gold 616C 7502U 872C 4515C 4515C 4515C 7553U Columbia 7682C 7682C 7459U 7462U 7462U* 7462U 7682C Brown Black 4C 4675C 412C 412C Black 4C 412U Pink 203C 5025C 5025C 5025C 203C Mid Blue 2747U 2945U Old Gold 1395C 7511C 7557C 7557C 1395C 126C Bright Yellow P 4-8C Maize 109C 130C 115U 7408C 7406C* 7406C 115U 137C Canyon Gold 7569C Tan 465U Texas Orange 7586C 7586C 7586C Tenn. -

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Descriptions and Records of Bees - LV

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Co Bee Lab 12-1-1913 Descriptions and Records of Bees - LV T. D. A. Cockerell University of Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_co Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Cockerell, T. D. A., "Descriptions and Records of Bees - LV" (1913). Co. Paper 509. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_co/509 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Bee Lab at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Co by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J,---f/--.~ /Jfo:J....._ ;/_. /.-c./;J...c- /Vtn'H:,·~4.-e- Af~:" edt/.,,/:J..~-c-,;-.._,..'\1/•n:,u.,'(.. ,E"°..__,-'t,,.,,s, 'P~Lf..-6Sofi j Ir. 1 F,-0111th e ANNALS AN[) MAGA7.INR OF NATURA[, Ilr STORV, Ser 8, Yol. xii., D ece111bn·19L:1. Descriptions and Rec1J1·ds of Bees.-L V. By 'r. D. A. CocrrnnELL, Univer sity of Colorado . Nomia muscosa, Cockerell. This w~s described from the female; the male l1ardly differs in appearance, and ha.s the hind legs very little modified. 'rhe hind tibi re ha ve white l1air on t he onter side, and short, shining, purpli sh-brown hair on the inner, only well seen in an oblique view. The antcnnre arv dark . 1\Iales before me are from 1\iackay_, Qu een land, Jan., March, ovember, 1900 (Turner, 618), and ew South ·wales (Nat . Mus. Victoria, 71). Nomia hippophila purnongens is, snh p. -

RAL Colour Chart

RAL COLOURS RAL 1000 Green beige RAL 1001 Beige RAL 1002 Sand yellow RAL 1003 Signal yellow RAL 1004 Golden yellow RAL 1005 Honey yellow RAL 1006 Maize yellow RAL 1007 Daffodil yellow RAL 1011 Brown beige RAL 1012 Lemon yellow RAL 1013 Oyster white RAL 1014 Dark Ivory RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 1016 Sulfur yellow RAL 1017 Saffron yellow RAL 1018 Zinc yellow RAL 1019 Grey beige RAL 1020 Olive yellow RAL 1021 Rape yellow RAL 1023 Traffic yellow RAL 1024 Ochre yellow RAL 1027 Curry RAL 1028 Melon yellow RAL 1032 Broom yellow RAL 1033 Dahlia yellow RAL 1034 Pastel yellow RAL 2000 Yellow orange RAL 2001 Red orange RAL 2002 Vermilion RAL 2003 Pastel orange RAL 2004 Pure orange RAL 2008 Bright red orange RAL 2009 Traffic orange RAL 2010 Signal orange RAL 2011 Deep orange RAL 2012 Salmon orange RAL 3000 Flame red RAL 3001 Signal red RAL 3002 Carmine red RAL 3003 Ruby red RAL 3004 Purple red RAL 3005 Wine red RAL 3007 Black red RAL 3009 Oxide red RAL 3011 Brown red RAL 3012 Beige red RAL 3013 Tomato red RAL 3014 Antique pink RAL 3015 Light pink RAL 3016 Coral red RAL 3017 Rose RAL 3018 Strawberry red RAL 3020 Traffic red RAL 3022 Salmon pink RAL 3027 Rasberry red RAL 3031 Orient red RAL 4001 Red lilac RAL 4002 Red violet RAL 4003 Heather violet RAL 4004 Claret violet RAL 4005 Blue lilac RAL 4006 Traffic purple RAL 4007 Purple violet RAL 4008 Signal violet RAL 4009 Pastel violet RAL 4010 Tele magenta RAL 5000 Violet blue RAL 5001 Green blue RAL 5002 Ultramarine RAL 5003 Sapphire blue RAL 5004 Black blue RAL 5005 Signal blue RAL 5007 Brilliant blue -

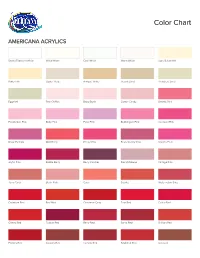

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

Flavors Ptablet Spec Sheet

Product Specifications FLAVORS 18" STACK CHAIR WITH P-TABLET ARM The shell is high density polypropylene material with color throughout and a shallow seat pan allowing “four- position” seating. The back supplies rigid support while being specifically designed with added flexibility that adapts to individual requirements and supplies long lasting comfort. The chair frame is constructed of strong 1“ x 16-gauge tubing that is chrome plated for a long lasting durable finish and is capped off with our durable nylon base swivel glides (steel and felt also available). The shell is attached to 16 gauge brackets via a metal to metal steel riveted connection. 14.00 P-Tablet Attachement The P-Tablet Frame is constructed of 7/8” diameter x 16 gauge steel tubing attached to 12 gauge steel plate with a chrome finish. The P-Tablet frame is securely fastened to the steel chair frame using 4 machine screws. The laminated top is made of 3/4” high density particle board with your choice or laminate and bullet T- Mold color. The laminate P-Tablet top fastens securely to the P-Tablet frame using 8 wood screws through the 22.00 clamps over the frame tubing into the top. The ‘belly room’ gap between the Tablet and seat back is roughly 14”. *Please note this measurement can be adjusted to your preference on site at installation. 28.50 Model Numbers Right Hand P-Tablet 11820v Left Hand P-Tablet 11821v Optional Accessories -17231 Book Rack (Mounted under the seat) Dimensions 22.0" W x 31.5" D x 31.25 H" Freight Weight: 18 lbs. -

—Hence, Tirade

e. —hence , t irad to: literary a misfits digital monthly from: robocup zine press FEBRUARY 2018 | THE LOVE + HATE ISSUE. I don't know how to write love letters. -Frida Kahlo t w o table of contents plasmatic valentine 2 by tamryn spruill micro poem from The Twitter Hive Mind Is Dreaming 5 by jackie wang lost color 6 by katy ilonka i do 7 by judy swann love & hate playlists 8 by nottheboyevan monthly [horoscapes] 10 by matthew burnside blue is the warmest color movie review 12 by her head in films knock knock 13 by j. bradley coming next month ... 14 tuesday 15 by adrian slonaker nothing more to tell 16 by mitchell krockmalnik grabois the collection 20 by sarah etlinger contributor bios 22 acknowledgments 25 —hence, tirade. f SUBMIT o SUBSCRIBE u r www.robocup-press.com Copyright 2018 © Robocup Press. I'm beingI'm being cooked from thecooked from the inside by myinside by my desire. desire. -Jackie Wang Pre-orders for her forthcoming Twitter-poem collection begin 3/3! 5 Lost Color Katy Ilonka I cannot find it. Pushed bark into bloodshot birds and the irises that smell of the times you were here and it has gone. I have heard of a professor who studies the passage of time building a machine that brings the eyes into a single space and places the color precisely. I have heard of a yogi mechanic who adjusts the color with a chakra wrench until it glows just right. I have heard of the times our steps were in sync. -

Desks & Tables

Desks & Tables Today’s learning environments present an unprecedented challenge to desks and tables, demanding greater versatility and durability. Our desks and tables are designed for multiple reconfigurations — pods, pairs, rows and more — and are reinforced to withstand the constant movement. Built for Learning. 84 Desks & Tables Interchange® Elemental® See page 88 See page 122 UXL® Silhouette® See page 142 See page 154 Planner® Meeting Tables See page 168 See page 204 86 www.smithsystem.com | 800.328.1061 Beyond design, consider how it’s engineered and built. Mobile Functionality In collaborative learning classrooms, students have to • “Pie-shaped” desktops allow students to make be able to move desks and tables without help. compact pods for working in groups. • Casters provide needed mobility for the desk — Reconfigurable don’t make students drag them across the floor. Today, the shape of desk and table work surfaces must • The suggested minimum workspace is 27 inches. allow the furniture to fit into a compact pod for small group work and work in pairs, or make them suitable for Durability individual work. • Structural Framing — steel reinforcing beams attach to each leg, adding rigidity and preventing wobbly Future Proof legs. Don’t settle for Easy On Brackets on tables Desks and tables are moved constantly. They must be and desks in collaborative learning classrooms. built strong to withstand this use well into the future. • The T-Mold edge band, used on Smith System Desks Their shapes must add functionality with future use and Tables, is stapled every 6 inches to provide in mind, rather than contributing gimmicky, non- superior fastening power. -

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\Color{Airforceblueraf}\#5D8aa8

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\color{airforceblueraf}\#5d8aa8} #5d8aa8 Air Force Blue (Usaf) {\color{airforceblueusaf}\#00308f} #00308f Air Superiority Blue {\color{airsuperiorityblue}\#72a0c1} #72a0c1 Alabama Crimson {\color{alabamacrimson}\#a32638} #a32638 Alice Blue {\color{aliceblue}\#f0f8ff} #f0f8ff Alizarin Crimson {\color{alizarincrimson}\#e32636} #e32636 Alloy Orange {\color{alloyorange}\#c46210} #c46210 Almond {\color{almond}\#efdecd} #efdecd Amaranth {\color{amaranth}\#e52b50} #e52b50 Amber {\color{amber}\#ffbf00} #ffbf00 Amber (Sae/Ece) {\color{ambersaeece}\#ff7e00} #ff7e00 American Rose {\color{americanrose}\#ff033e} #ff033e Amethyst {\color{amethyst}\#9966cc} #9966cc Android Green {\color{androidgreen}\#a4c639} #a4c639 Anti-Flash White {\color{antiflashwhite}\#f2f3f4} #f2f3f4 Antique Brass {\color{antiquebrass}\#cd9575} #cd9575 Antique Fuchsia {\color{antiquefuchsia}\#915c83} #915c83 Antique Ruby {\color{antiqueruby}\#841b2d} #841b2d Antique White {\color{antiquewhite}\#faebd7} #faebd7 Ao (English) {\color{aoenglish}\#008000} #008000 Apple Green {\color{applegreen}\#8db600} #8db600 Apricot {\color{apricot}\#fbceb1} #fbceb1 Aqua {\color{aqua}\#00ffff} #00ffff Aquamarine {\color{aquamarine}\#7fffd4} #7fffd4 Army Green {\color{armygreen}\#4b5320} #4b5320 Arsenic {\color{arsenic}\#3b444b} #3b444b Arylide Yellow {\color{arylideyellow}\#e9d66b} #e9d66b Ash Grey {\color{ashgrey}\#b2beb5} #b2beb5 Asparagus {\color{asparagus}\#87a96b} #87a96b Atomic Tangerine {\color{atomictangerine}\#ff9966} #ff9966 Auburn {\color{auburn}\#a52a2a} #a52a2a Aureolin -

HOW to IDENTIFY the FIVE SALMON SPECIES Found in the KODIAK ISLAND/ALASKA PENINSULA AREA

HOW TO IDENTIFY the FIVE SALMON SPECIES found in the KODIAK ISLAND/ALASKA PENINSULA AREA KING (CHINOOK) SALMON: COHO (SILVER) SALMON: Greenish-blue Blue-gray back with silvery sides. Small, irregular- back with silvery sides. Small black spots on the back, shaped black spots on back, dorsal fi n, and usually on dorsal fi n, and both lobes of the tail. usually on Black mouth with white upper lobe gums at base of teeth on of tail lower jaw. only. Spawning coho salmon adults develop Black mouth with black gums greenish-black heads and dark brown to at base of teeth on lower jaw. maroon bodies. Salmon mouth illustrations courtesy of California Department Fish and Game SOCKEYE (RED) SALMON: Dark blue-black back with silvery sides. No distinct Spawning spots on back, king salmon dorsal fi n, adults lose their or tail. silvery bright color and take Spawning sockeye salmon adults develop dull on a maroon to olive brown color. green colored heads and brick-red to scarlet bodies. CHUM (DOG) SALMON: Dull gray back PINK SALMON (HUMPIES): with yellowish-silver sides. Very large spots on the back No distinct spots on back and large black oval blotches or tail. Large eye pupil— on both tail lobes. Very small covers nearly the entire eye. scales. Spawning adults take on a dull gray coloration on the back and Spawning adults develop olive green upper sides with a creamy white coloration on the back with maroon color below. Males develop a sides covered with irregular dull red pronounced hump. bars. Males exhibit many large canine- like teeth. -

Cashmere Collection 100% Cashmere

Cashmere Collection 100% Cashmere Lemonade Melon Pink Grapefruit Robin’s Egg Blue Grey Heather White Wasabi Fireball Lavender Nautical Blue Charcoal Oatmeal Aloe Green Carnival Red Magenta Abyss Earth Heather Owl Jade Sangria Blush Navy Blue Black Autumn Leaf Cashmere Collection Style 3101 Abyss Magenta Autumn Leaf Melon Black Nautical Blue Blush Navy Blue Carnival Red Oatmeal Charcoal Owl Fireball Pink Grapefruit Grey Heather Robin’s Egg Blue Jade Sangria V-Neck Lavender White Lemonade Sizes: M-L-XL-XXL Cashmere Collection Style 4102 Black Charcoal Grey Heather Magenta Navy Blue Sangria Crew Neck Sizes: M-L-XL-XXL Cashmere Collection Style 4103 Autumn Leaf with Stone Heather Black with Charcoal Charcoal with Stone Heather Nautical Blue with Stone Heather Robin’s Egg Blue with Stone Heather Sangria with Charcoal Zip Mock Neck with contrast collar lining Sizes: M-L-XL-XXL Cashmere Collection Style 3105 Black Carnival Red Charcoal Lemonade Nautical Blue Navy Blue Sangria Sleeveless V-Neck Sizes: M-L-XL-XXL Cashmere Collection Style 7117 Sangria with Charcoal Black with Charcoal Quilted Zip Vest with pockets Sizes: M-L-XL-XXL Cashmere Collection Style 8106 Earth Heather Grey Heather Nautical Blue Robin’s Egg Blue Sangria Multi-Cable Button Mock Neck Sizes: M-L-XL-XXL Merino Wool Collection 100% Extra Fine Merino Wool Stone Heather Marigold Pear Green Cozumel Pale Lilac Goldenrod Ash Grey Brown Sugar Clover Periwinkle Crepe Myrtle Solar Flare Gunmetal Chestnut Vine Green Nocturnal Blue Plum Royale Deep Red Black Dark Brown Heather Olive Heather