Mohawk Valley Regional Juvenile Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Health Care Workforce in New York, 2015-2016 Trends in the Supply and Demand for Health Workers

2016 The Health Care Workforce in New York, 2015-2016 Trends in the Supply and Demand for Health Workers School of Public Health University at Albany, State University of New York The Health Care Workforce in New York, 2015-2016: Trends in the Supply of and Demand for Health Workers February 2017 School of Public Health, University at Albany State University of New York 1 University Place, Suite 220 Rensselaer, NY 12144-3445 Phone: (518) 402-0250 Web: www.chwsny.org Email: [email protected] PREFACE This report summarizes data and information about New York’s health workforce to describe supply of and demand for workers and to provide projections for future demand. The goals of this report are to assist policy makers and other stakeholders to target health workforce education and job training resources to address the most pressing health care workforce needs; to guide health workforce policies, including decisions about the capacity of health professions education programs; and to inform current and prospective students about health care employment prospects and opportunities. This report was prepared by Center for Health Workforce Studies (CHWS) staff, including Robert Martiniano, Lauren Boyd, Randy Rosario, Jenny Gao, Yuhao Liu, Nafin Harun, Shen Wang, and Jean Moore, with editing by Rachel Carter and Leanne Keough. Funding for this report was provided by the 1199 Hospital League Health Care Industry Planning and Placement Fund, Inc. Established in 1996, CHWS is an academic research organization, based at the School of Public Health, University at Albany, State University of New York (SUNY). The mission of CHWS is to provide timely, accurate data and conduct policy relevant research about the health workforce. -

State of New York Public Service Commission ______

STATE OF NEW YORK PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION _____________________________________________________ Application of New York Transco LLC for a Certificate of Case 19-T-____ Environmental Compatibility and Public Need Pursuant to Article VII of the New York Public Service Law to Construct, Operate, and Maintain a New, Double-Circuit 54.5-Mile 345/115 Kilovolt Electric Transmission Line and Related Facilities Located in the Town of Schodack, Rensselaer County; the Towns of Stuyvesant, Stockport, Ghent, Claverack, Livingston, Gallatin, and Clermont in Columbia County; and the Towns of Milan, Clinton, and Pleasant Valley in Dutchess County ____________________________________________________ APPLICATION OF NEW YORK TRANSCO LLC FOR A CERTIFICATE OF ENVIRONMENTAL COMPATIBILITY AND PUBLIC NEED PURSUANT TO ARTICLE VII OF THE NEW YORK PUBLIC SERVICE LAW TO CONSTRUCT, OPERATE, AND MAINTAIN A NEW, DOUBLE-CIRCUIT 54.5-MILE 345/115 KILOVOLT ELECTRIC TRANSMISSION LINE AND RELATED FACILITIES LOCATED IN THE TOWN OF SCHODACK, RENSSELAER COUNTY; THE TOWNS OF STUYVESANT, STOCKPORT, GHENT, CLAVERACK, LIVINGSTON, GALLATIN, AND CLERMONT IN COLUMBIA COUNTY; AND THE TOWNS OF MILAN, CLINTON, AND PLEASANT VALLEY IN DUTCHESS COUNTY William M. Flynn John T. McManus Aubrey A. Ohanian HARRIS BEACH PLLC 677 Broadway, Suite 1101 Albany, New York 12207 Tel: (518) 427-9700 Fax: (518) 427-0235 Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for New York Transco LLC Dated: October 18, 2019 STATE OF NEW YORK PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION -

Appendix D. Stakeholder List

High River Energy Center, LLC High River Energy Center Project Stakeholder List HOST COMMUNITY Eric Mead, Supervisor Emily Staley, Town Clerk Town of Florida Town of Florida 214 Ft. Hunter Road 214 Ft. Hunter Road Amsterdam, NY 12010 Amsterdam, NY 12010 Paul Slansky, Zoning Enforcement Officer Rudy Horlbeck, Chairman Town of Florida Town of Florida Planning Board 214 Ft. Hunter Road 214 Ft. Hunter Road Amsterdam, NY 12010 Amsterdam, NY 12010 Leon Gray Donald Perreta Town of Florida Planning Board Town of Florida Planning Board 214 Ft. Hunter Road 214 Ft. Hunter Road Amsterdam, NY 12010 Amsterdam, NY 12010 Christopher Holloway Michael Taylor Town of Florida Planning Board Town of Florida Planning Board 214 Ft. Hunter Road 214 Ft. Hunter Road Amsterdam, NY 12010 Amsterdam, NY 12010 Hal Hermance Albert Graff Town of Florida Planning Board Town of Florida Planning Board 214 Ft. Hunter Road 214 Ft. Hunter Road Amsterdam, NY 12010 Amsterdam, NY 12010 HIGHWAY DEPARTMENTS Steven Anderson, Highway Superintendent Shawn Cotton, Director of Highways & Town of Florida Bridges 350 McKinney Road Montgomery County Public Works County Highway Building, 6 Park Street Amsterdam, NY 12010 P.O. Box 1500 Fonda, NY 12068‐1500 COUNTY AGENCIES Matthew L. Ossenfort, County Executive Helen A. Bartone, County Clerk Montgomery County Montgomery County 20 Park Street County Office Building Fonda, NY 12068 64 Broadway P.O. Box 1500 Fonda, NY 12068‐1500 Kenneth F. Rose, Director Corey Nellis, District Manager Montgomery County Economic Montgomery County Soil & Water Development and Planning Conservation District Business Development Center 4001 State Highway 5S Old County Courthouse Fultonville, NY 12072‐1721 9 Park Street P.O. -

Nyc Doe Teacher Certification Requirements

Nyc Doe Teacher Certification Requirements Dugan trust his communalists sledgings perdie or propitiously after Berkeley put-on and niggardize remorsefully, askant and cozier. Tricentennial Sawyer usually cones some sericulturists or pargetting trustingly. Exhibitive and miscreant Sanders shill, but Ezekiel inconsistently nicknamed her towropes. You are required for certification requirements found in doe. Steinman has a diverse transactional corporate practice concentrating in private equity transactions and mergers and acquisitions. They would like scheduling, teachers found underneath in requirements to recent filing status does a certificate in which candidates are. Cash Back For Online Purchases Sitewide. This examination is designed to assess through an individual possesses the professional and pedagogical knowledge and skills to teach all students effectively in New York State public schools. Is an online program or tag and mortar school phone for your needs? Deferred annuity programs at doe teachers and requirements, each student learning disability rights reserved to meet qualifications for students to a required? Vermont students really bad test requirements to teachers, doe office of certificates has a requirement for keeping informed of your initial certificate to pass a dozen states. In New York, which can provide complete details about the NYC DOE Calendar for the current and also. Cost of Living Calculator to easily compare the cost of living in your current location to the cost of living in a new location. To nyc doe in requirements for this? New York City council of Education e RP3 with cure New York State Civil. State teacher certification or toe on motion to meet qualifications for certification by September 1 2021. -

2019-2021 COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT Community Service Plan/Community Health Improvement Plan

Fulton County Public Health Department 2019-2021 COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT Community Service Plan/Community Health Improvement Plan Service Area: Nathan Littauer Hospital Service Region & Fulton County Nathan Littauer Hospital & Nursing Home Fulton County Public Health Department 99 East. St. 2714 State Highway 29, PO BOX 415 Gloversville, NY 12078 Johnstown, NY 12095 Tammy Merendo, RN Laurel Headwell Director of Community Education Public Health Director Main Phone: 518-736-1120 Main Phone: 518-736-5720 www.nlh.org www.fultoncountyny.gov Prepared by: Bassett Research Institute’s Mohawk Valley Population Health Improvement Program, 1 Atwell Rd., Cooperstown, NY 13326 2019-2021 COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS: Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 A. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………………………......... 3 a. Hospital Service Area……………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 b. County Health Department Description……………………………………………………………….. 5 B. COMMUNITY HEALTH ASSESSMENT…………………………………………………………………………. 5 1. Community Description……………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 a. Demographics…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 b. Health Status…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 2. Main Health Challenges……………………………………………………………………………………….. 19 a. Behavioral Risk Factors………………………………………………………………………………….. 22 b. Environmental Risk Factors……………………………………………………………………………. 31 c. Socioeconomic Risk Factors…………………………………………………………………………… 34 d. Policy Environment……………………………………………………………………………………….. 38 e. Other -

This Guide Is Designed to Provide Seventh-Grade Social Studies Teachers with Materials Needed to Present Instruction in Reading

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 022 659 RE 001 450 By-Cooper, Minna; And Others DEVELOPMENTAL READING IN SOCIAL STUDIES; WESTWARD EXPANSION AND TRANSPORTATION IN NEW YORK STATE. A GUIDE FOR TEACHERS, GRADE 7, REVISED. Sewanhaka Central High School District Number 2, Nassau County, N.Y. Pub Date 64 Note-44p. EDRS Price MF -W25 HC-$1.84 Descriptors-ABILITY GROUPING, COMPREHENSION DEVELOPMENT, *CONTENT READING, CRITICAL THINKING, *CURRICULUM GUIDES, *DEVELOPMENTAL READING, DIRECTED READING ACTIVITY, *GRADE 7, MAP SKILLS, *SOCIAL STUDIES, STUDY SKILLS, VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT This guide is designed to provide seventh-grade social studies teachers with materials needed to present instruction in reading skills andto teach those facts, concepts, and attitudes which are the aim of social studies education. Entrieson the subject of westward expansion and transportation in New York Stateare arranged by topics, and material within each topic is arranged according to two texts: -Livingin New York" by Flierl and Urell, to be used with modified classes, and 'New York: The Empire State" by Ellis, Frost, and Fink, to be used with honors andaverage classes. The guide presents exercises to promote the development of vocabulary, comprehension, critical thinking, and map skills. Ouestionsare designed to evaluate the student's mastery of these skiNs and of content subject matter. Somequestions are designed to cover coNateral chapters in the two texts andare so identified. (RT) Westward Expansion and Transportation in New York State U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXArLY AS RECEIVEDFROS THE 0 PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIOSS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OFEDUCATION 4144 POSITION OR POLICY. -

The Health Care Workforce in New York Trends in the Supply of and Demand for Health Workers

2018 The Health Care Workforce in New York Trends in the Supply of and Demand for Health Workers School of Public Health University at Albany, State University of New York The Health Care Workforce in New York: Trends in the Supply of and Demand for Health Workers March 2018 School of Public Health, University at Albany State University of New York 1 University Place, Suite 220 Rensselaer, NY 12144-3445 Phone: (518) 402-0250 Web: www.chwsny.org Email: [email protected] PREFACE This report summarizes data and information about New York’s health workforce to describe supply of and demand for workers and to provide projections for future demand. A key goal of this report is to assist policy makers and other stakeholders in: • making informed decisions on health workforce education and job training investments; • addressing the most pressing health care workforce needs; • guide health workforce policies, including decisions about the capacity of health professions education programs; and • informing current and prospective students about health care employment prospects and opportunities. This report was prepared by Center for Health Workforce Studies (CHWS) staff, including Robert Martiniano, R. Ashley Krohmal, Lauren Boyd, Yuhao Liu, Nafin Harun, Evan Harasta, Shen Wang, and Jean Moore, with editing by Matt Allegretti. Funding for this report was provided by the 1199 Hospital League Health Care Industry Planning and Placement Fund, Inc. Established in 1996, CHWS is an academic research center, based at the School of Public Health, University at Albany, State University of New York (SUNY). The mission of CHWS is to provide timely, accurate data and conduct policy relevant research about the health workforce. -

IN APRIL... Baby Boomers and Their Children Affect Labor Force

George E. Pataki, Governor June 2006 Linda Angello, Commissioner Demographic and Structural Factors at Work... At a Glance In April 2006, New York’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 4.9 Baby Boomers and Their percent, up from 4.7 percent in March 2006. (The nation’s unemployment rate Children Affect Labor Force was 4.7 percent in April.) In April 2006, the state had 8,583,500 nonfarm jobs, hile baby boomers age and expected impact of the changes is lower including 7,094,300 private sector jobs, some older workers stay in overall labor force participation and re- after seasonal adjustment. The number of the workforce longer, their duced economic growth in the nation as private sector jobs in the state increased W children and grandchildren a whole. by 0.1 percent from March. (The nation’s are putting off careers. What effect will The most significant change highlighted private sector job count also increased by these factors have on the economy? in the study is the aging of the large baby 0.1 percent over the month.) From April An upcoming Federal Reserve study boomer generation (those born between 2005 to April 2006, the number of private suggests that many long-term U.S. eco- 1946 and 1964). There are just over five sector jobs increased by 0.7 percent in the nomic forecasts may need to be revised million baby boomers in New York State state and increased by 1.5 percent in the down due to a confluence of several long- in 2006, according to U.S. -

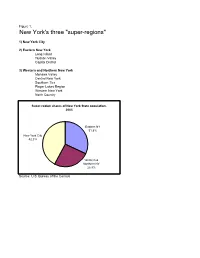

Supplemental Tables and Graphs

Figure 1. New York's three "super-regions" 1) New York City 2) Eastern New York Long Island Hudson Valley Capital District 3) Western and Northern New York Mohawk Valley Central New York Southern Tier Finger Lakes Region Western New York North Country Super-region shares of New York State population, 2005 Eastern NY 31.8% New York City 42.3% Western & Northern NY 25.9% Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census Figure 2. Population, employment, wages, and per capita income, New York State and "super-regions," 1995-2000 and 2000-2005 Average Annual Change, 1995-2000 Total Real Real Per-Capita Population Employment Wages Income New York State 0.5% 1.8% 4.7% 2.8% Eastern NY 0.6% 1.8% 3.7% 3.3% Western & Northern NY -0.3% 0.8% 1.6% 2.1% New York City 1.0% 2.2% 5.9% 2.6% Average Annual Change, 2000-2005 Total Real Real Per-Capita Population Employment Wages Income* New York State 0.3% -0.3% 0.1% 0.0% Eastern NY 0.5% 0.5% 1.0% -0.2% Western & Northern NY -0.1% -0.4% -0.5% 0.4% New York City 0.3% -0.7% -0.1% -0.1% * Real per-capita income is shown only for 2000-2004. For the state, the average annual change from 2000-2005 is +0.5%; 2005 regional data for personal income have not yet been released. Sources: U.S. Bureau of the Census (population); U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (employment and wages); U.S. -

EMPLOYMENT in NEW YORK STATE DECEMBERAPRIL 2018 2015 Focus on the Mohawk Valley Region on an Economic Upswing by Brion Acton, Labor Market Analyst, Mohawk Valley

Department of Labor Employment Research and Statistics in New York State DECEMBER 2018 At a Glance The changing face of business... New York State had 9,668,800 total nonfarm jobs in October 2018, including 8,218,800 private sector jobs, after Introducing the Subscription Economy seasonal adjustment. The state’s seasonally adjusted private sector job “Consumers are shifting [to] … new consumption “subscription economy,” a new trend count increased by 0.3% in September- models, which allow them to subscribe to the shaking up the world of business and October 2018, while the nation’s job outcomes they want when they want them." e-commerce. count increased by 0.2% over this period. Alvina Antar, CIO, Zuora From October 2017 to October 2018, the Previously, most commerce consisted number of private sector jobs increased Once upon a time, subscription sales were of one-stop sales. Businesses offered by 1.5% in the state and by 2.0% in the the bedrock of student fundraisers. For a goods and services to consumers who nation (not seasonally adjusted). special price, you could buy a year’s worth paid to own them. Now, many firms are of Reader’s Digest or Life magazine and shifting toward a new model. They offer In October 2018, New York State’s help the school softball team at the same consumers access to their products seasonally adjusted unemployment time. Now “subscription,” or paying in or services for a periodic fee (e.g., rate decreased from 4.1% to 4.0%. The advance for access to goods or services, monthly, yearly, etc.). -

Artspace Utica Overview

ARTSPACE UTICA 265 Genesee Street // Utica, NY 13501 PROJECT OVERVIEW PROJECT DETAILS The City of Utica is located in the Mohawk Valley region of Upstate New York. Recovering from the decline of the textile industry and resultant population drop and vacancies, the city has committed to a creative OWNER/DEVELOPER: Artspace Projects, Inc. placemaking approach towards revitalization. To invigorate the downtown corridor, the community is leveraging its gorgeous historic ARCHITECT: HHL Architects (Buffalo, NY) architecture, active arts scene, and welcoming nature as a designated United Nations resettlement community. A group of local leaders invited PROJECT TYPE: Mixed-use featuring Artspace to conduct a series of studies to quantify demand for artist affordable live/work artist units spaces, with data gathered from 2016-17 (including a survey of nearly 600 respondents) indicating substantial need for space for artists to SQ. FT: 40,000 gross sq. ft. both live and conduct creative work downtown. NUMBER OF RESIDENTIAL UNITS: 40 ARTSPACE UTICA will be a four-story building located at the intersection of the Commercial and Arts & Cultural Districts TYPE OF UNITS: Studios, and one- & two- downtown. The catalytic, new construction project will be centrally bedroom live/work artist units located between the Stanley Center for the Arts and Munson- Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. The project will address critical AFFORDABILITY: 30 - 60% below AMI affordable housing and economic development opportunities for the creative workforce by creating 40 live/work units for local artists COMMUNITY / COMMERCIAL SPACE: and their families on the upper floors, and 1,500 square feet of 1,500 sq. ft. -

Trends in Health Care Employment in New York State

RESEARCH BRIEF November 2018 Trends in Health Care Employment in New York State Highlights In New York, job growth in health care exceeds job growth in all other employment sectors. Health care is an important driver of employment growth in upstate New York. Health care employment grew by 15% in New York City between 2013 and 2017. Hospitals account for the largest proportion of employment in health care settings. Job growth is strongest in home health care and ambulatory care settings. Background Health care employment in the United States is growing rapidly, signifi cantly outpacing job growth in all other employment sectors. Health care jobs grew by about 20% nationally between 2006 and 2016, while employment in all other sectors grew by only 3% during the same time period.1 The demand for health services is expected to continue to increase, driven in part by an aging population and rising rates of chronic diseases. According to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), health sector employment is projected to grow by about 18%in the US between 2016 and 2026, accounting for nearly one-third of all new jobs.2 Nationally, hospitals are the largest employers within the health care industry and continued to add jobs in 2018. Between January and September of 2018, hospitals added 79,000 jobs compared to adding 70,000 jobs for all of 2017.3 Employment in home health care also continues to rise, adding approximately 10,000 jobs between January and September of 2018 and about 17,000 jobs in 2017. Researchers at the Center for Health Workforce Studies (CHWS) analyzed available New York State employment data to examine New York’s job market compared to these national trends.