Jewish Carnality and the Eucharist in Jörg Ratgeb's Herrenberg Altarpiece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karen Knorr CV 16 Sept 2020

Karen Knorr CURRICULUM VITAE [email protected] www.karenknorr.com American, British dual national, born Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1954. Lives and works in London. Currently Professor of Photography at University for the Creative Arts, Farnham BA/ MFA Photography EDUCATION 1958 - 1963 San Juan School, Santurce, Puerto Rico 1963 - 1972 Saint John’s Preparatory School, Condado, Puerto Rico 1972 - 1973 Franconia College, New Hampshire, USA 1973 - 1976 L’Atelier, Rue de Seine, Paris, France 1977 - 1980 BA Hons (First) Polytechnic of Central London (University of Westminster), England 1988 - 1980 M.A.University of Derby, England MONOGRAPHS AND CATALOGUES 2018 Another Way of Telling, New Stories from India and Japan, Karen Knorr & Shiho Kito, Nishieda Foundation, Kyoto 2016 Gentlemen, Karen Knorr, Stanley/Barker, London, England 2015 Belgravia, Karen Knorr, Stanley/Barker, London, England 2014 India Song, Karen Knorr, SKIRA, Italy 2013 Punks, Karen Knorr And Olivier Richon, GOST Books, London, England India Song catalogue, Tasveer Gallery, India 2012 Karen Knorr, El Ojo Que Ves, La Fabrica, University of Cordoba, Spain 2010 Transmigrations, Tasveer Gallery, Bangalore, India 2008 Fables, Filigranes Publishers, with texts by Lucy Soutter and Nathalie LeLeu, Paris, France 2002 Genii Loci, Black Dog Publishing, texts by Antonio Guzman, David Campany and interview by Rebecca Comay, London, England 2001 Karen Knorr par Antonio Guzman, Frac Basse Normandie, France 1991 Signes de Distinction, essay by Patrick Mauries, Thames and Hudson, France Marks -

Annals of Psi Upsilon 1833-1941 the Heraldry

THE HERALDRY OF PSI UPSILON By Clayton W. Butterfield, Pi '11 Certain emblems were generally used in English Heraldry to indicate whether a 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, etc., son of a family was the bearer of arms. In Biblical history, every man among the Children of Israel was or dered to pitch his camp by his own standard�no doubt an individual sign or emblem. Various explanations are given to the origin of the various units which make up a coat-of-arms. The early warriors are said to have painted their shields or covered them with metal or furs so that they might be or Just as the various divisions of the readily identified distinguished in when the war army are today identified by the in battle, particularly riors were in their coats signia on their equipment, or on the of mail. The idea is also unifonns of the men, so in the early given credence that when a warrior returned a ages various tribes and warriors from could be identified by the emblems battle, he hung his shield on the wall and symbols which served as their or placed it on a big chair-like rack particular marks of distinction. in the great hall, and above it his a Not only did a tribe have its dis placed helmet. Sometimes hel tinctive identifying mark, but fami- met was decorated with the colors Hes, too, used emblems to show their and ribbons of the warrior's lady fair. A warrior's coat-of-arms was in hneage or allegiance. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

The Overseas Chevron Controversy and Canadian Identity in the Great War

Canadian Military History Volume 20 Issue 3 Article 5 2011 Side-Steppers and Original-Firsts: The Overseas Chevron Controversy and Canadian Identity in the Great War Andrew Iarocci Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Iarocci, Andrew "Side-Steppers and Original-Firsts: The Overseas Chevron Controversy and Canadian Identity in the Great War." Canadian Military History 20, 3 (2011) This Canadian War Museum is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iarocci: Side-Steppers and Original-Firsts Side-Steppers and Original-Firsts The Overseas Chevron Controversy and Canadian Identity in the Great War Andrew Iarocci he Great War was more than Canadians were killed or wounded auxiliaries who had served overseas Tthree years old by the end of at Vimy between 9 and 14 April.1 for extended periods. 1917 and there was no end in sight. The Dominion of Canada, with fewer In the context of a global conflict From the Allied perspective 1917 than 8 million people, would need to that claimed millions of lives and had been an especially difficult year impose conscription if its forces were changed the geo-political landscape with few hopeful moments. On the to be maintained at fighting strength. of the modern world, it may seem Western Front, French General Robert In the meantime, heavy fighting trifling to devote an article to a Nivelle’s grand plans for victory had continued in Artois throughout simple military badge that did not failed with heavy losses, precipitating the summer of 1917. -

The Rights of War and Peace Book I

the rights of war and peace book i natural law and enlightenment classics Knud Haakonssen General Editor Hugo Grotius uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu ii ii ii iinatural law and iienlightenment classics ii ii ii ii ii iiThe Rights of ii iiWar and Peace ii iibook i ii ii iiHugo Grotius ii ii ii iiEdited and with an Introduction by iiRichard Tuck ii iiFrom the edition by Jean Barbeyrac ii ii iiMajor Legal and Political Works of Hugo Grotius ii ii ii ii ii ii iiliberty fund ii iiIndianapolis ii uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 b.c. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash. ᭧ 2005 Liberty Fund, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 c 54321 09 08 07 06 05 p 54321 Frontispiece: Portrait of Hugo de Groot by Michiel van Mierevelt, 1608; oil on panel; collection of Historical Museum Rotterdam, on loan from the Van der Mandele Stichting. Reproduced by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grotius, Hugo, 1583–1645. [De jure belli ac pacis libri tres. English] The rights of war and peace/Hugo Grotius; edited and with an introduction by Richard Tuck. p. cm.—(Natural law and enlightenment classics) “Major legal and political works of Hugo Grotius”—T.p., v. -

Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Faculty Publications Jewish Studies 2020 Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs Part of the History Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fordham University, "Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate" (2020). Faculty Publications. 2. https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jewish Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Media Technology & The Dissemination of Hate November 15th, 2019-May 31st 2020 O’Hare Special Collections Fordham University & Center for Jewish Studies Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Highlights from the Fordham Collection November 15th, 2019-May 31st, 2020 Curated by Sally Brander FCRH ‘20 Clare McCabe FCRH ‘20 Magda Teter, The Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies with contributions from Students from the class HIST 4308 Antisemitism in the Fall of 2018 and 2019 O’Hare Special Collections Walsh Family Library, Fordham University Table of Contents Preface i Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate 1 Christian (Mis)Interpretation and (Mis)Representation of Judaism 5 The Printing Press and The Cautionary Tale of One Image 13 New Technology and New Opportunities 22 -

The Last Supper Seen Six Ways by Louis Inturrisi the New York Times, March 23, 1997

1 Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper, in a former convent refectory that is now a museum. The Last Supper Seen Six Ways By Louis Inturrisi The New York Times, March 23, 1997 When I was 9 years old, I painted the Last Supper. I did it on the dining room table at our home in Connecticut on Saturday afternoon while my mother ironed clothes and hummed along with the Texaco. Metropolitan Operative radio broadcast. It took me three months to paint the Last Supper, but when I finished and hung it on my mother's bedroom wall, she assured me .it looked just like Leonardo da Vinci's painting. It was supposed to. You can't go very wrong with a paint-by-numbers picture, and even though I didn't always stay within the lines and sometimes got the colors wrong, the experience left me with a profound respect for Leonardo's achievement and a lingering attachment to the genre. So last year, when the Florence Tourist Bureau published a list of frescoes of the Last Supper that are open to the public, I was immediately on their track. I had seen several of them, but never in sequence. During the Middle Ages the ultima cena—the final supper Christ shared with His disciples before His arrest and crucifixion—was part of any fresco cycle that told His life story. But in the 15th century the Last Supper began to appear independently, especially in the refectories, or dining halls, of the convents and monasteries of the religious orders founded during the Middle Ages. -

Read the Conference Program

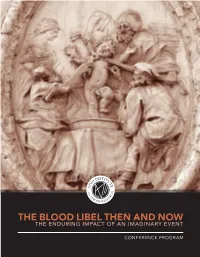

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

Holy Monday St. John 12:1-23 March 29Th, 2021 Sts. Peter and Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church, UAC Simpsonville, SC Pastor Jerald Dulas

Holy Monday St. John 12:1-23 March 29th, 2021 Sts. Peter and Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church, UAC Simpsonville, SC Pastor Jerald Dulas Mary Anointed the Feet of Jesus In Nomine Iesu! In the Name of the Father and of the + Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen. Prayer in Pulpit before Sermon: O Lord, send out Thy Light and Thy Truth, let them lead us. O Lord, open Thou my lips, that my mouth may show forth Thy praise. O Lord, graciously preserve me, lest that by any means, when I have preached to others, I myself should be rejected. Amen. Grace, mercy, and peace be to you from God our Father and from our Lord and Savior + Jesus Christ. Amen. From the crowds rejoicing and cheering our Lord + Jesus into Jerusalem in yesterday’s Gospel, we are taken to our Lord’s suffering and burial. Indeed, we will be presented with our Lord’s Passion every day this week as we approach Good Friday and the crucifixion of our Lord on the tree of the holy cross for the atonement of the whole world and the justification of all those who cling to this work of Him in faith. We are taken to the death of our Lord + Jesus by Mary, the sister of Martha, and even more significant, the sister of Lazarus, who was risen from the dead by the Lord + Jesus. Mary takes us to our Lord’s death and burial, because she anoints the feet of our Lord with very costly—three hundred denarii worth—spikenard. -

Jerg-Ratgeb-Skulpturenpfad.Pdf

Skulpturenpfad 2012 Projektgruppe Herrenberger Jerg-Ratgeb-Skulpturenpfad Walter Grandjot (Projektsprecher), Stephanie Brachtl (Stellv.), Marline Fetzer-Hauser, Bernd Winckler Prof. Helge Bathelt (Projektpate und künstl. Sachverstand) Walter Grandjot, Jettinger Str. 42, 71083 Herrenberg-Kuppingen Tel. 07032-33403, mob. 0172-9425773, email: [email protected] Stand: 04.03.2012 - 1 - Der Pfad. Ein gerader Weg. ... vom Bahnhof durch die historische Altstadt zum Schlossberg. - 2 - Skulptur 1 Bahnhof Hellmut Ehrath im Besitz von Doris Ehrath - 3 - Inhalte Ehrath Diese Arbeit war bereits auf dem Skulpturenpfad „EigenArt“ zum Landesjubiläum 2003 vertreten. Dort hat sich eine Lesart heraus gebildet, die den Absichten des Künstlers entspricht. Aus einem strengen, durch seine Kanten dargestellten Würfel, erhebt sich, entflieht, steigt auf, eine Figuration, die in knappen, zerrissenen, verschlissenen Formen gestaltet ist. Beine, Arme, ein Corpus und ein Kopf sind unschwer auszumachen. Die als widersprüchlich inszenierten Materialien – das stumpfe (Gefängnisgitter(?), das Eisen und der gleißende Edelstahl, die stereometrisch klare gegenüber der freien Form geben der Arbeit eine hohe Lesbarkeit: Sie wird dem Betrachter zu einem Fanal einer Freiheit, die sich über alles Festgelegte und Einengende erhebt. Die Arbeit wird dadurch im Jerg Ratgeb Pfad absolut stimmig. zum Künstler Hellmut Ehrath 16. August 1938 in Oberndorf am Neckar; † 13. September 2008 in Herrenberg), Bildhauer und Graphiker. Biografie Ab 1955 machte Hellmut Ehrath nach einer Lehre erste Berufserfahrungen als Grafischer Zeichner. Von 1958 bis 1962 studierte er an der Akademie der Bildenden Künste Stuttgart freie Graphik und Malerei bei den Professoren Rolf Daudert und Manfred Henninger. Danach reiste er vor allem in mehrere Länder des Nahen Ostens und in den Sudan. -

St. Elijah Orthodox Christian Church

ST. ELIJAH ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN CHURCH 15000 N. May, Oklahoma City, OK 73134 Church Office: 755-7804 Church Website: www.stelijahokc.com Church Email: [email protected] APRIL 5, 2020 Issue 32 Number 14 Fifth Sunday of Great Lent (Commemoration of our Righteous Mother Mary of Egypt); Saints of the Day: Martyrs Claudius, Diodore and their companions; New-Martyr George of New Ephesus; Venerable Theodora and Didymus of Alexandria DIRECTORY WELCOME V. Rev. Fr. John Salem Parish Priest 410-9399 We welcome all our visitors. It is an honor to have you worshipping with us. You may find the worship of the Rev. Fr. Elias Khouri Ancient Church very different. We welcome your questions. Assistant Priest 640-3016 Please join us for our Reception held in the Church Hall V. Rev. Fr. Constantine Nasr immediately following the Divine Liturgy. Emeritus We understand Holy Communion to be an act of our unity in Rev. Dn. Ezra Ham faith. While we work toward the unity of all Christians, it Administrator 602-9914 regrettably does not now exist. Therefore, only baptized Rev. Fr. Ambrose Perry Orthodox Christians (who have properly prepared) are Attached permitted to participate in Holy Communion. However, everyone is welcome to partake of the blessed bread that is Anthony Ruggerio 847-721-5192 distributed at the end of the service. We look forward to Youth Director meeting you during the Reception that follows the service. Mom’s Day Out & Pre-K NEW ORTHROS & LITURGY BOOK Sara Cortez – Director 639-2679 Orthros: p. 4 Email: [email protected] Facebook: “St Elijah Mom’s Day Out” The Divine Liturgy p. -

Ontdek Schilder Jerg Ratgeb

65669 Jerg Ratgeb man / Duits schilder Naamvarianten In dit veld worden niet-voorkeursnamen zoals die in bronnen zijn aangetroffen, vastgelegd en toegankelijk gemaakt. Dit zijn bijvoorbeeld andere schrijfwijzen, bijnamen of namen van getrouwde vrouwen met of juist zonder de achternaam van een echtgenoot. Rathgeb, Jörg Schürzjürgen SchürzJörgen Kwalificaties schilder Nationaliteit/school Duits Geboren Herrenberg (Stuttgart)/Schwäbisch Gmünd 1480/1485 born (around) 1480-85 Herrenberg / Schwäbisch Gmünd (AKLONLINE March 2018); Stoppel 2011: bron in Schwäbisch Gmünd between 1470/75 and 1480 Overleden Pforzheim 1526 Deze persoon/entiteit in andere databases 1 treffer in RKDimages als kunstenaar 4 treffers in RKDlibrary als onderwerp 2 treffers in RKDtechnical als onderzochte kunstenaar Verder zoeken in RKDartists& Geboren 1480 Sterfplaats Pforzheim Plaats van werkzaamheid Italië Plaats van werkzaamheid Stuttgart Plaats van werkzaamheid Heilbronn Plaats van werkzaamheid Hessen (deelstaat) Plaats van werkzaamheid Frankfurt am Main Plaats van werkzaamheid Herrenberg (Stuttgart) Kwalificaties schilder Onderwerpen christelijk religieuze voorstelling Biografische gegevens Werkzaam in Hier wordt vermeld waar de kunstenaar (langere tijd) heeft gewerkt en in welke periode. Ook relevante studiereizen worden hier vermeld. Italië 1500 long study stay in Italy around 1500 Stuttgart 1503 - 1509-04 Stoppel 2011 Heilbronn 1509-04 - 1512 Stoppel 2011 Hessen (deelstaat) 1511 - 1514 Hirschhorn Frankfurt am Main 1514 - 1517 Herrenberg (Stuttgart) 1518 - 1519 Stuttgart 1520 - 1525 Onderwerpen In dit veld worden de diverse onderwerpscategorieën of genres vermeld die in het oeuvre van de beschreven kunstenaar voorkomen. De inhoud van dit veld is doorgaans meer gebaseerd op het aanwezige beeldmateriaal in het RKD dan op de literatuur. christelijk religieuze voorstelling Literatuur Literatuur in RKDLibrary 4 treffers in RKDlibrary als onderwerp Thieme/Becker 1907-1950 , vol.