A Three-Factor Model of Syllogistic Reasoning: the Study of Isolable Stages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

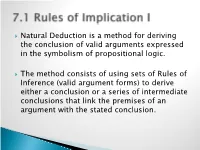

7.1 Rules of Implication I

Natural Deduction is a method for deriving the conclusion of valid arguments expressed in the symbolism of propositional logic. The method consists of using sets of Rules of Inference (valid argument forms) to derive either a conclusion or a series of intermediate conclusions that link the premises of an argument with the stated conclusion. The First Four Rules of Inference: ◦ Modus Ponens (MP): p q p q ◦ Modus Tollens (MT): p q ~q ~p ◦ Pure Hypothetical Syllogism (HS): p q q r p r ◦ Disjunctive Syllogism (DS): p v q ~p q Common strategies for constructing a proof involving the first four rules: ◦ Always begin by attempting to find the conclusion in the premises. If the conclusion is not present in its entirely in the premises, look at the main operator of the conclusion. This will provide a clue as to how the conclusion should be derived. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in the consequent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via modus ponens. ◦ If the conclusion contains a negated letter and that letter appears in the antecedent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining the negated letter via modus tollens. ◦ If the conclusion is a conditional statement, consider obtaining it via pure hypothetical syllogism. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a disjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via disjunctive syllogism. Four Additional Rules of Inference: ◦ Constructive Dilemma (CD): (p q) • (r s) p v r q v s ◦ Simplification (Simp): p • q p ◦ Conjunction (Conj): p q p • q ◦ Addition (Add): p p v q Common Misapplications Common strategies involving the additional rules of inference: ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a conjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via simplification. -

Saving the Square of Opposition∗

HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF LOGIC, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1080/01445340.2020.1865782 Saving the Square of Opposition∗ PIETER A. M. SEUREN Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, the Netherlands Received 19 April 2020 Accepted 15 December 2020 Contrary to received opinion, the Aristotelian Square of Opposition (square) is logically sound, differing from standard modern predicate logic (SMPL) only in that it restricts the universe U of cognitively constructible situations by banning null predicates, making it less unnatural than SMPL. U-restriction strengthens the logic without making it unsound. It also invites a cognitive approach to logic. Humans are endowed with a cogni- tive predicate logic (CPL), which checks the process of cognitive modelling (world construal) for consistency. The square is considered a first approximation to CPL, with a cognitive set-theoretic semantics. Not being cognitively real, the null set Ø is eliminated from the semantics of CPL. Still rudimentary in Aristotle’s On Interpretation (Int), the square was implicitly completed in his Prior Analytics (PrAn), thereby introducing U-restriction. Abelard’s reconstruction of the logic of Int is logically and historically correct; the loca (Leak- ing O-Corner Analysis) interpretation of the square, defended by some modern logicians, is logically faulty and historically untenable. Generally, U-restriction, not redefining the universal quantifier, as in Abelard and loca, is the correct path to a reconstruction of CPL. Valuation Space modelling is used to compute -

Traditional Logic II Text (2Nd Ed

Table of Contents A Note to the Teacher ............................................................................................... v Further Study of Simple Syllogisms Chapter 1: Figure in Syllogisms ............................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Mood in Syllogisms ................................................................................................. 5 Chapter 3: Reducing Syllogisms to the First Figure ............................................................... 11 Chapter 4: Indirect Reduction of Syllogisms .......................................................................... 19 Arguments in Ordinary Language Chapter 5: Translating Ordinary Sentences into Logical Statements ..................................... 25 Chapter 6: Enthymemes ......................................................................................................... 33 Hypothetical Syllogisms Chapter 7: Conditional Syllogisms ......................................................................................... 39 Chapter 8: Disjunctive Syllogisms ......................................................................................... 49 Chapter 9: Conjunctive Syllogisms ......................................................................................... 57 Complex Syllogisms Chapter 10: Polysyllogisms & Aristotelian Sorites .................................................................. 63 Chapter 11: Goclenian & Conditional Sorites ........................................................................ -

Common Sense for Concurrency and Strong Paraconsistency Using Unstratified Inference and Reflection

Published in ArXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/0812.4852 http://commonsense.carlhewitt.info Common sense for concurrency and strong paraconsistency using unstratified inference and reflection Carl Hewitt http://carlhewitt.info This paper is dedicated to John McCarthy. Abstract Unstratified Reflection is the Norm....................................... 11 Abstraction and Reification .............................................. 11 This paper develops a strongly paraconsistent formalism (called Direct Logic™) that incorporates the mathematics of Diagonal Argument .......................................................... 12 Computer Science and allows unstratified inference and Logical Fixed Point Theorem ........................................... 12 reflection using mathematical induction for almost all of Disadvantages of stratified metatheories ........................... 12 classical logic to be used. Direct Logic allows mutual Reification Reflection ....................................................... 13 reflection among the mutually chock full of inconsistencies Incompleteness Theorem for Theories of Direct Logic ..... 14 code, documentation, and use cases of large software systems Inconsistency Theorem for Theories of Direct Logic ........ 15 thereby overcoming the limitations of the traditional Tarskian Consequences of Logically Necessary Inconsistency ........ 16 framework of stratified metatheories. Concurrency is the Norm ...................................................... 16 Gödel first formalized and proved that it is not possible -

To Determine the Validity of Categorical Syllogisms

arXiv:1509.00926 [cs.LO] Using Inclusion Diagrams – as an Alternative to Venn Diagrams – to Determine the Validity of Categorical Syllogisms Osvaldo Skliar1 Ricardo E. Monge2 Sherry Gapper3 Abstract: Inclusion diagrams are introduced as an alternative to using Venn diagrams to determine the validity of categorical syllogisms, and are used here for the analysis of diverse categorical syllogisms. As a preliminary example of a possible generalization of the use of inclusion diagrams, consideration is given also to an argument that includes more than two premises and more than three terms, the classic major, middle and minor terms in categorical syllogisms. Keywords: inclusion diagrams, Venn diagrams, categorical syllogisms, set theory Mathematics Subject Classification: 03B05, 03B10, 97E30, 00A66 1. Introduction Venn diagrams [1] have been and continue to be used to introduce syllogistics to beginners in the field of logic. These diagrams are perhaps the main technical tool used for didactic purposes to determine the validity of categorical syllogisms. The objective of this article is to present a different type of diagram, inclusion diagrams, to make it possible to reach one of the same objectives for which Venn diagrams were developed. The use of these new diagrams is not only simple and systematic but also very intuitive. It is natural and quite obvious that if one set is included in another set, which in turn, is included in a third set, then the first set is part of the third set. This result, an expression of the transitivity of the inclusion relation existing between sets, is the primary basis of inclusion diagrams. -

Aristotle and Gautama on Logic and Physics

Aristotle and Gautama on Logic and Physics Subhash Kak Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, LA 70803-5901 February 2, 2008 Introduction Physics as part of natural science and philosophy explicitly or implicitly uses logic, and from this point of view all cultures that studied nature [e.g. 1-4] must have had logic. But the question of the origins of logic as a formal discipline is of special interest to the historian of physics since it represents a turning inward to examine the very nature of reasoning and the relationship between thought and reality. In the West, Aristotle (384-322 BCE) is gener- ally credited with the formalization of the tradition of logic and also with the development of early physics. In India, the R. gveda itself in the hymn 10.129 suggests the beginnings of the representation of reality in terms of various logical divisions that were later represented formally as the four circles of catus.kot.i: “A”, “not A”, “A and not A”, and “not A and not not A” [5]. Causality as the basis of change was enshrined in the early philosophical sys- tem of the S¯am. khya. According to Pur¯an. ic accounts, Medh¯atithi Gautama and Aks.ap¯ada Gautama (or Gotama), which are perhaps two variant names for the same author of the early formal text on Indian logic, belonged to about 550 BCE. The Greek and the Indian traditions seem to provide the earliest formal arXiv:physics/0505172v1 [physics.gen-ph] 25 May 2005 representations of logic, and in this article we ask if they influenced each other. -

Traditional Logic and Computational Thinking

philosophies Article Traditional Logic and Computational Thinking J.-Martín Castro-Manzano Faculty of Philosophy, UPAEP University, Puebla 72410, Mexico; [email protected] Abstract: In this contribution, we try to show that traditional Aristotelian logic can be useful (in a non-trivial way) for computational thinking. To achieve this objective, we argue in favor of two statements: (i) that traditional logic is not classical and (ii) that logic programming emanating from traditional logic is not classical logic programming. Keywords: syllogistic; aristotelian logic; logic programming 1. Introduction Computational thinking, like critical thinking [1], is a sort of general-purpose thinking that includes a set of logical skills. Hence logic, as a scientific enterprise, is an integral part of it. However, unlike critical thinking, when one checks what “logic” means in the computational context, one cannot help but be surprised to find out that it refers primarily, and sometimes even exclusively, to classical logic (cf. [2–7]). Classical logic is the logic of Boolean operators, the logic of digital circuits, the logic of Karnaugh maps, the logic of Prolog. It is the logic that results from discarding the traditional, Aristotelian logic in order to favor the Fregean–Tarskian paradigm. Classical logic is the logic that defines the standards we typically assume when we teach, research, or apply logic: it is the received view of logic. This state of affairs, of course, has an explanation: classical logic works wonders! However, this is not, by any means, enough warrant to justify the absence or the abandon of Citation: Castro-Manzano, J.-M. traditional logic within the computational thinking literature. -

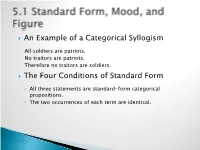

5.1 Standard Form, Mood, and Figure

An Example of a Categorical Syllogism All soldiers are patriots. No traitors are patriots. Therefore no traitors are soldiers. The Four Conditions of Standard Form ◦ All three statements are standard-form categorical propositions. ◦ The two occurrences of each term are identical. ◦ Each term is used in the same sense throughout the argument. ◦ The major premise is listed first, the minor premise second, and the conclusion last. The Mood of a Categorical Syllogism consists of the letter names that make it up. ◦ S = subject of the conclusion (minor term) ◦ P = predicate of the conclusion (minor term) ◦ M = middle term The Figure of a Categorical Syllogism Unconditional Validity Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 AAA EAE IAI AEE EAE AEE AII AIA AII EIO OAO EIO EIO AOO EIO Conditional Validity Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 Required Conditio n AAI AEO AEO S exists EAO EAO AAI EAO M exists EAO AAI P exists Constructing Venn Diagrams for Categorical Syllogisms: Seven “Pointers” ◦ Most intuitive and easiest-to-remember technique for testing the validity of categorical syllogisms. Testing for Validity from the Boolean Standpoint ◦ Do shading first ◦ Never enter the conclusion ◦ If the conclusion is already represented on the diagram the syllogism is valid Testing for Validity from the Aristotelian Standpoint: 1. Reduce the syllogism to its form and test from the Boolean standpoint. 2. If invalid from the Boolean standpoint, and there is a circle completely shaded except for one region, enter a circled “X” in that region and retest the form. 3. If the form is syllogistically valid and the circled “X” represents something that exists, the syllogism is valid from the Aristotelian standpoint. -

Aristotle's Theory of the Assertoric Syllogism

Aristotle’s Theory of the Assertoric Syllogism Stephen Read June 19, 2017 Abstract Although the theory of the assertoric syllogism was Aristotle’s great invention, one which dominated logical theory for the succeeding two millenia, accounts of the syllogism evolved and changed over that time. Indeed, in the twentieth century, doctrines were attributed to Aristotle which lost sight of what Aristotle intended. One of these mistaken doctrines was the very form of the syllogism: that a syllogism consists of three propositions containing three terms arranged in four figures. Yet another was that a syllogism is a conditional proposition deduced from a set of axioms. There is even unclarity about what the basis of syllogistic validity consists in. Returning to Aristotle’s text, and reading it in the light of commentary from late antiquity and the middle ages, we find a coherent and precise theory which shows all these claims to be based on a misunderstanding and misreading. 1 What is a Syllogism? Aristotle’s theory of the assertoric, or categorical, syllogism dominated much of logical theory for the succeeding two millenia. But as logical theory de- veloped, its connection with Aristotle because more tenuous, and doctrines and intentions were attributed to him which are not true to what he actually wrote. Looking at the text of the Analytics, we find a much more coherent theory than some more recent accounts would suggest.1 Robin Smith (2017, §3.2) rightly observes that the prevailing view of the syllogism in modern logic is of three subject-predicate propositions, two premises and a conclusion, whether or not the conclusion follows from the premises. -

A Vindication of Program Verification 1. Introduction

June 2, 2015 13:21 History and Philosophy of Logic SB_progver_selfref_driver˙final A Vindication of Program Verification Selmer Bringsjord Department of Cognitive Science Department of Computer Science Lally School of Management & Technology Rensselaer AI & Reasoning Laboratory Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) Troy NY 12180 USA [email protected] Received 00 Month 200x; final version received 00 Month 200x Fetzer famously claims that program verification isn't even a theoretical possibility, and offers a certain argument for this far-reaching claim. Unfortunately for Fetzer, and like-minded thinkers, this position-argument pair, while based on a seminal insight that program verification, despite its Platonic proof-theoretic airs, is plagued by the inevitable unreliability of messy, real-world causation, is demonstrably self-refuting. As I soon show, Fetzer (and indeed anyone else who provides an argument- or proof-based attack on program verification) is like the person who claims: \My sole claim is that every claim expressed by an English sentence and starting with the phrase `My sole claim' is false." Or, more accurately, such thinkers are like the person who claims that modus tollens is invalid, and supports this claim by giving an argument that itself employs this rule of inference. 1. Introduction Fetzer (1988) famously claims that program verification isn't even a theoretical possibility,1 and seeks to convince his readers of this claim by providing what has now become a widely known argument for it. Unfortunately for Fetzer, and like-minded thinkers, this position-argument pair, while based on a seminal insight that program verification, despite its Platonic proof-theoretic airs, is plagued by the inevitable unreliability of messy, real-world causation, is demonstrably self-refuting. -

Module 3: Proof Techniques

Module 3: Proof Techniques Theme 1: Rule of Inference Let us consider the following example. Example 1: Read the following “obvious” statements: All Greeks are philosophers. Socrates is a Greek. Therefore, Socrates is a philosopher. This conclusion seems to be perfectly correct, and quite obvious to us. However, we cannot justify it rigorously since we do not have any rule of inference. When the chain of implications is more complicated, as in the example below, a formal method of inference is very useful. Example 2: Consider the following hypothesis: 1. It is not sunny this afternoon and it is colder than yesterday. 2. We will go swimming only if it is sunny. 3. If we do not go swimming, then we will take a canoe trip. 4. If we take a canoe trip, then we will be home by sunset. From this hypothesis, we should conclude: We will be home by sunset. We shall come back to it in Example 5. The above conclusions are examples of a syllogisms defined as a “deductive scheme of a formal argument consisting of a major and a minor premise and a conclusion”. Here what encyclope- dia.com is to say about syllogisms: Syllogism, a mode of argument that forms the core of the body of Western logical thought. Aristotle defined syllogistic logic, and his formulations were thought to be the final word in logic; they underwent only minor revisions in the subsequent 2,200 years. We shall now discuss rules of inference for propositional logic. They are listed in Table 1. These rules provide justifications for steps that lead logically to a conclusion from a set of hypotheses. -

Reasoning Through the Disjunctive Syllogism in Monkeys Research-Article9716532021

PSSXXX10.1177/0956797620971653Ferrigno et al.Reasoning Through the Disjunctive Syllogism in Monkeys 971653research-article2021 ASSOCIATION FOR Short Report PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Psychological Science 1 –9 Reasoning Through the Disjunctive © The Author(s) 2021 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions Syllogism in Monkeys DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620971653 10.1177/0956797620971653 www.psychologicalscience.org/PS Stephen Ferrigno1,2 , Yiyun Huang2,3, and Jessica F. Cantlon2,4 1Department of Psychology, Harvard University; 2Seneca Park Zoo, Rochester, NY; 3Department of Psychology, Yale University; and 4Department of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University Abstract The capacity for logical inference is a critical aspect of human learning, reasoning, and decision-making. One important logical inference is the disjunctive syllogism: given A or B, if not A, then B. Although the explicit formation of this logic requires symbolic thought, previous work has shown that nonhuman animals are capable of reasoning by exclusion, one aspect of the disjunctive syllogism (e.g., not A = avoid empty). However, it is unknown whether nonhuman animals are capable of the deductive aspects of a disjunctive syllogism (the dependent relation between A and B and the inference that “if not A, then B” must be true). Here, we used a food-choice task to test whether monkeys can reason through an entire disjunctive syllogism. Our results show that monkeys do have this capacity. Therefore, the capacity is not unique to humans and does not require language. Keywords reasoning, inference, logic, disjunctive syllogism, comparative cognition, primates Received 11/19/18; Revision accepted 8/5/20 Logical reasoning is an important aspect of human & Roeder, 2012; birds: Pepperberg et al., 2013; Schloegl learning, reasoning, and decision-making (Rips, 1994).