Aristotle's Theory of the Assertoric Syllogism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Thomas Geach, 1916–2013

PETER GEACH Peter Thomas Geach 1916–2013 PETER GEACH was born on 29 March 1916 at 41, Royal Avenue, Chelsea. He was the son of George Hender Geach, a Cambridge graduate working in the Indian Educational Service (IES), who later taught philosophy at Lahore. George Geach was married to Eleonore Sgnonina, the daughter of a Polish civil engineer who had emigrated to England. The marriage was not a happy one: after a brief period in India Eleonore returned to England to give birth and never returned to her husband. Peter Geach’s first few years were spent in the house of his Polish grandparents in Cardiff, but at the age of four his father had him made the ward of a former nanny of his own, an elderly nonconformist lady named Miss Tarr. When Peter’s mother tried to visit him, Miss Tarr warned him that a dangerous mad woman was coming, so that he cowered away from her when she tried to embrace him. As she departed she threw a brick through a window, and from that point there was no further contact between mother and son. When he was eight years old he became a boarder at Llandaff Cathedral School. Soon afterwards his father was invalided out of the IES and took charge of his education. To the surprise of his Llandaff housemaster, Peter won a scholarship to Clifton College, Bristol. Geach père had learnt moral sciences at Trinity College Cambridge from Bertrand Russell and G. E. Moore, and he inducted his son into the delights of philosophy from an early age. -

The Logic of Where and While in the 13Th and 14Th Centuries

The Logic of Where and While in the 13th and 14th Centuries Sara L. Uckelman Department of Philosophy, Durham University Abstract Medieval analyses of molecular propositions include many non-truthfunctional con- nectives in addition to the standard modern binary connectives (conjunction, dis- junction, and conditional). Two types of non-truthfunctional molecular propositions considered by a number of 13th- and 14th-century authors are temporal and local propositions, which combine atomic propositions with ‘while’ and ‘where’. Despite modern interest in the historical roots of temporal and tense logic, medieval analy- ses of ‘while’ propositions are rarely discussed in modern literature, and analyses of ‘where’ propositions are almost completely overlooked. In this paper we introduce 13th- and 14th-century views on temporal and local propositions, and connect the medieval theories with modern temporal and spatial counterparts. Keywords: Jean Buridan, Lambert of Auxerre, local propositions, Roger Bacon, temporal propositions, Walter Burley, William of Ockham 1 Introduction Modern propositional logicians are familiar with three kinds of compound propositions: Conjunctions, disjunctions, and conditionals. Thirteenth-century logicians were more liberal, admitting variously five, six, seven, or more types of compound propositions. In the middle of the 13th century, Lambert of Auxerre 1 in his Logic identified six types of ‘hypothetical’ (i.e., compound, as opposed to atomic ‘categorical’, i.e., subject-predicate, propositions) propo- sitions: the three familiar ones, plus causal, local, and temporal propositions [17, 99]. Another mid-13th century treatise, Roger Bacon’s Art and Science of Logic¶ , lists these six and adds expletive propositions (those which use the connective ‘however’), and other ones not explicitly classified such as “Socrates 1 The identity of the author of this text is not known for certain. -

6.5 the Recursion Theorem

6.5. THE RECURSION THEOREM 417 6.5 The Recursion Theorem The recursion Theorem, due to Kleene, is a fundamental result in recursion theory. Theorem 6.5.1 (Recursion Theorem, Version 1 )Letϕ0,ϕ1,... be any ac- ceptable indexing of the partial recursive functions. For every total recursive function f, there is some n such that ϕn = ϕf(n). The recursion Theorem can be strengthened as follows. Theorem 6.5.2 (Recursion Theorem, Version 2 )Letϕ0,ϕ1,... be any ac- ceptable indexing of the partial recursive functions. There is a total recursive function h such that for all x ∈ N,ifϕx is total, then ϕϕx(h(x)) = ϕh(x). 418 CHAPTER 6. ELEMENTARY RECURSIVE FUNCTION THEORY A third version of the recursion Theorem is given below. Theorem 6.5.3 (Recursion Theorem, Version 3 ) For all n ≥ 1, there is a total recursive function h of n +1 arguments, such that for all x ∈ N,ifϕx is a total recursive function of n +1arguments, then ϕϕx(h(x,x1,...,xn),x1,...,xn) = ϕh(x,x1,...,xn), for all x1,...,xn ∈ N. As a first application of the recursion theorem, we can show that there is an index n such that ϕn is the constant function with output n. Loosely speaking, ϕn prints its own name. Let f be the recursive function such that f(x, y)=x for all x, y ∈ N. 6.5. THE RECURSION THEOREM 419 By the s-m-n Theorem, there is a recursive function g such that ϕg(x)(y)=f(x, y)=x for all x, y ∈ N. -

April 22 7.1 Recursion Theorem

CSE 431 Theory of Computation Spring 2014 Lecture 7: April 22 Lecturer: James R. Lee Scribe: Eric Lei Disclaimer: These notes have not been subjected to the usual scrutiny reserved for formal publications. They may be distributed outside this class only with the permission of the Instructor. An interesting question about Turing machines is whether they can reproduce themselves. A Turing machine cannot be be defined in terms of itself, but can it still somehow print its own source code? The answer to this question is yes, as we will see in the recursion theorem. Afterward we will see some applications of this result. 7.1 Recursion Theorem Our end goal is to have a Turing machine that prints its own source code and operates on it. Last lecture we proved the existence of a Turing machine called SELF that ignores its input and prints its source code. We construct a similar proof for the recursion theorem. We will also need the following lemma proved last lecture. ∗ ∗ Lemma 7.1 There exists a computable function q :Σ ! Σ such that q(w) = hPwi, where Pw is a Turing machine that prints w and hats. Theorem 7.2 (Recursion theorem) Let T be a Turing machine that computes a function t :Σ∗ × Σ∗ ! Σ∗. There exists a Turing machine R that computes a function r :Σ∗ ! Σ∗, where for every w, r(w) = t(hRi; w): The theorem says that for an arbitrary computable function t, there is a Turing machine R that computes t on hRi and some input. Proof: We construct a Turing Machine R in three parts, A, B, and T , where T is given by the statement of the theorem. -

Intuitionism on Gödel's First Incompleteness Theorem

The Yale Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 2 Issue 1 Spring 2021 Article 31 2021 Incomplete? Or Indefinite? Intuitionism on Gödel’s First Incompleteness Theorem Quinn Crawford Yale University Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yurj Part of the Mathematics Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Crawford, Quinn (2021) "Incomplete? Or Indefinite? Intuitionism on Gödel’s First Incompleteness Theorem," The Yale Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 31. Available at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yurj/vol2/iss1/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Yale Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Incomplete? Or Indefinite? Intuitionism on Gödel’s First Incompleteness Theorem Cover Page Footnote Written for Professor Sun-Joo Shin’s course PHIL 437: Philosophy of Mathematics. This article is available in The Yale Undergraduate Research Journal: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yurj/vol2/iss1/ 31 Crawford: Intuitionism on Gödel’s First Incompleteness Theorem Crawford | Philosophy Incomplete? Or Indefinite? Intuitionism on Gödel’s First Incompleteness Theorem By Quinn Crawford1 1Department of Philosophy, Yale University ABSTRACT This paper analyzes two natural-looking arguments that seek to leverage Gödel’s first incompleteness theo- rem for and against intuitionism, concluding in both cases that the argument is unsound because it equivo- cates on the meaning of “proof,” which differs between formalism and intuitionism. -

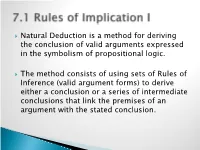

7.1 Rules of Implication I

Natural Deduction is a method for deriving the conclusion of valid arguments expressed in the symbolism of propositional logic. The method consists of using sets of Rules of Inference (valid argument forms) to derive either a conclusion or a series of intermediate conclusions that link the premises of an argument with the stated conclusion. The First Four Rules of Inference: ◦ Modus Ponens (MP): p q p q ◦ Modus Tollens (MT): p q ~q ~p ◦ Pure Hypothetical Syllogism (HS): p q q r p r ◦ Disjunctive Syllogism (DS): p v q ~p q Common strategies for constructing a proof involving the first four rules: ◦ Always begin by attempting to find the conclusion in the premises. If the conclusion is not present in its entirely in the premises, look at the main operator of the conclusion. This will provide a clue as to how the conclusion should be derived. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in the consequent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via modus ponens. ◦ If the conclusion contains a negated letter and that letter appears in the antecedent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining the negated letter via modus tollens. ◦ If the conclusion is a conditional statement, consider obtaining it via pure hypothetical syllogism. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a disjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via disjunctive syllogism. Four Additional Rules of Inference: ◦ Constructive Dilemma (CD): (p q) • (r s) p v r q v s ◦ Simplification (Simp): p • q p ◦ Conjunction (Conj): p q p • q ◦ Addition (Add): p p v q Common Misapplications Common strategies involving the additional rules of inference: ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a conjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via simplification. -

Chapter 1 Logic and Set Theory

Chapter 1 Logic and Set Theory To criticize mathematics for its abstraction is to miss the point entirely. Abstraction is what makes mathematics work. If you concentrate too closely on too limited an application of a mathematical idea, you rob the mathematician of his most important tools: analogy, generality, and simplicity. – Ian Stewart Does God play dice? The mathematics of chaos In mathematics, a proof is a demonstration that, assuming certain axioms, some statement is necessarily true. That is, a proof is a logical argument, not an empir- ical one. One must demonstrate that a proposition is true in all cases before it is considered a theorem of mathematics. An unproven proposition for which there is some sort of empirical evidence is known as a conjecture. Mathematical logic is the framework upon which rigorous proofs are built. It is the study of the principles and criteria of valid inference and demonstrations. Logicians have analyzed set theory in great details, formulating a collection of axioms that affords a broad enough and strong enough foundation to mathematical reasoning. The standard form of axiomatic set theory is denoted ZFC and it consists of the Zermelo-Fraenkel (ZF) axioms combined with the axiom of choice (C). Each of the axioms included in this theory expresses a property of sets that is widely accepted by mathematicians. It is unfortunately true that careless use of set theory can lead to contradictions. Avoiding such contradictions was one of the original motivations for the axiomatization of set theory. 1 2 CHAPTER 1. LOGIC AND SET THEORY A rigorous analysis of set theory belongs to the foundations of mathematics and mathematical logic. -

Theorem Proving in Classical Logic

MEng Individual Project Imperial College London Department of Computing Theorem Proving in Classical Logic Supervisor: Dr. Steffen van Bakel Author: David Davies Second Marker: Dr. Nicolas Wu June 16, 2021 Abstract It is well known that functional programming and logic are deeply intertwined. This has led to many systems capable of expressing both propositional and first order logic, that also operate as well-typed programs. What currently ties popular theorem provers together is their basis in intuitionistic logic, where one cannot prove the law of the excluded middle, ‘A A’ – that any proposition is either true or false. In classical logic this notion is provable, and the_: corresponding programs turn out to be those with control operators. In this report, we explore and expand upon the research about calculi that correspond with classical logic; and the problems that occur for those relating to first order logic. To see how these calculi behave in practice, we develop and implement functional languages for propositional and first order logic, expressing classical calculi in the setting of a theorem prover, much like Agda and Coq. In the first order language, users are able to define inductive data and record types; importantly, they are able to write computable programs that have a correspondence with classical propositions. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Steffen van Bakel, my supervisor, for his support throughout this project and helping find a topic of study based on my interests, for which I am incredibly grateful. His insight and advice have been invaluable. I would also like to thank my second marker, Nicolas Wu, for introducing me to the world of dependent types, and suggesting useful resources that have aided me greatly during this report. -

Chapter 10: Symbolic Trails and Formal Proofs of Validity, Part 2

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine CHAPTER 10: SYMBOLIC TRAILS AND FORMAL PROOFS OF VALIDITY, PART 2 Introduction In the previous chapter there were many frustrating signs that something was wrong with our formal proof method that relied on only nine elementary rules of validity. Very simple, intuitive valid arguments could not be shown to be valid. For instance, the following intuitively valid arguments cannot be shown to be valid using only the nine rules. Somalia and Iran are both foreign policy risks. Therefore, Iran is a foreign policy risk. S I / I Either Obama or McCain was President of the United States in 2009.1 McCain was not President in 2010. So, Obama was President of the United States in 2010. (O v C) ~(O C) ~C / O If the computer networking system works, then Johnson and Kaneshiro will both be connected to the home office. Therefore, if the networking system works, Johnson will be connected to the home office. N (J K) / N J Either the Start II treaty is ratified or this landmark treaty will not be worth the paper it is written on. Therefore, if the Start II treaty is not ratified, this landmark treaty will not be worth the paper it is written on. R v ~W / ~R ~W 1 This or statement is obviously exclusive, so note the translation. 427 If the light is on, then the light switch must be on. So, if the light switch in not on, then the light is not on. L S / ~S ~L Thus, the nine elementary rules of validity covered in the previous chapter must be only part of a complete system for constructing formal proofs of validity. -

Saving the Square of Opposition∗

HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF LOGIC, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1080/01445340.2020.1865782 Saving the Square of Opposition∗ PIETER A. M. SEUREN Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, the Netherlands Received 19 April 2020 Accepted 15 December 2020 Contrary to received opinion, the Aristotelian Square of Opposition (square) is logically sound, differing from standard modern predicate logic (SMPL) only in that it restricts the universe U of cognitively constructible situations by banning null predicates, making it less unnatural than SMPL. U-restriction strengthens the logic without making it unsound. It also invites a cognitive approach to logic. Humans are endowed with a cogni- tive predicate logic (CPL), which checks the process of cognitive modelling (world construal) for consistency. The square is considered a first approximation to CPL, with a cognitive set-theoretic semantics. Not being cognitively real, the null set Ø is eliminated from the semantics of CPL. Still rudimentary in Aristotle’s On Interpretation (Int), the square was implicitly completed in his Prior Analytics (PrAn), thereby introducing U-restriction. Abelard’s reconstruction of the logic of Int is logically and historically correct; the loca (Leak- ing O-Corner Analysis) interpretation of the square, defended by some modern logicians, is logically faulty and historically untenable. Generally, U-restriction, not redefining the universal quantifier, as in Abelard and loca, is the correct path to a reconstruction of CPL. Valuation Space modelling is used to compute -

Traditional Logic II Text (2Nd Ed

Table of Contents A Note to the Teacher ............................................................................................... v Further Study of Simple Syllogisms Chapter 1: Figure in Syllogisms ............................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Mood in Syllogisms ................................................................................................. 5 Chapter 3: Reducing Syllogisms to the First Figure ............................................................... 11 Chapter 4: Indirect Reduction of Syllogisms .......................................................................... 19 Arguments in Ordinary Language Chapter 5: Translating Ordinary Sentences into Logical Statements ..................................... 25 Chapter 6: Enthymemes ......................................................................................................... 33 Hypothetical Syllogisms Chapter 7: Conditional Syllogisms ......................................................................................... 39 Chapter 8: Disjunctive Syllogisms ......................................................................................... 49 Chapter 9: Conjunctive Syllogisms ......................................................................................... 57 Complex Syllogisms Chapter 10: Polysyllogisms & Aristotelian Sorites .................................................................. 63 Chapter 11: Goclenian & Conditional Sorites ........................................................................ -

Reviving Material Theories of Induction John P. Mccaskey 1

Reviving Material Theories of Induction John P. McCaskey 1. Reviving material theories of induction John D. Norton says that philosophers have been led astray for thousands of years by their attempt to treat induction formally (Norton, 2003, 2005, 2010, 2014, 2019). He is correct that such an attempt has caused no end of trouble, but he is wrong about the history. There is a rich tradition of non-formal induction in the writings of, among others, Aristotle, Cicero, John Buridan, Lorenzo Valla, Rudolph Agricola, Peter Ramus, Francis Bacon, and William Whewell. In fact, material theories of induction prevailed all through antiquity and from the Renaissance to the mid-1800s. Recovering these past systems would not only fill lacunae in Norton’s own theory but would highlight areas where Norton has not freed himself from the straightjacket of formal induction as much as he might think. The effort might also help us build a new theory of induction on the ground Norton has cleared for us. This essay begins that recovery and invites that rebuilding.1 2. Formal vs. Material theories of induction The distinction between formal and material theories of induction was first drawn, at least under those names, in the 1840s. The inductive system of Francis Bacon had prevailed for two hundred years, and some philosophers were starting to complain about that, most influentially a professor at Oxford University named Richard Whately.2 Bacon’s induction was an extension of Renaissance classification logic (“topics-logic”). It was orderly and methodical, but it was not 1 The essay will not defend particular formal systems against Norton’s attacks.