Ruth Park a Celebration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book History in Australia Since 1950 Katherine Bode Preprint: Chapter 1

Book History in Australia since 1950 Katherine Bode Preprint: Chapter 1, Oxford History of the Novel in English: The Novel in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the South Pacific since 1950. Edited by Coral Howells, Paul Sharrad and Gerry Turcotte. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. Publication of Australian novels and discussion of this phenomenon have long been sites for the expression of wider tensions between national identity and overseas influence characteristic of postcolonial societies. Australian novel publishing since 1950 can be roughly divided into three periods, characterized by the specific, and changing, relationship between national and non-national influences. In the first, the 1950s and 1960s, British companies dominated the publication of Australian novels, and publishing decisions were predominantly made overseas. Yet a local industry also emerged, driven by often contradictory impulses of national sentiment, and demand for American-style pulp fiction. In the second period, the 1970s and 1980s, cultural nationalist policies and broad social changes supported the growth of a vibrant local publishing industry. At the same time, the significant economic and logistical challenges of local publishing led to closures and mergers, and—along with the increasing globalization of publishing—enabled the entry of large, multinational enterprises into the market. This latter trend, and the processes of globalization and deregulation, continued in the final period, since the 1990s. Nevertheless, these decades have also witnessed the ongoing development and consolidation of local publishing of Australian novels— including in new forms of e-publishing and self-publishing—as well as continued government and social support for this activity, and for Australian literature more broadly. -

The Development of Fantasy Illustration in Australian Children's Literature

The University of Tasmania "THE SHADOW LINE BETWEEN REALITY AND FANTASY": THE DEVELOPMENT OF FANTASY ILLUSTRATION IN AUSTRALIAN CHILDREN'S LITERATURE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Degree for Master of Education. Centre of Education by Irene Theresa Gray University of Tasmania December 1985. Acknowledgments I wish to thank the following persons for assistance in the presentation of this dissertation: - Mr. Hugo McCann, Centre for Education, University of Tasmania for his encouragement, time, assistance and critical readership of this document. Mr. Peter Johnston, librarian and colleague who kindly spent time in the word processing and typing stage. Finally my husband, Andrew whose encouragement and support ensured its completion. (i) ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to show that accompanying a development of book production and printing techniques in Australia, there has been a development in fantasy illustration in Australian children's literature. This study has identified the period of Australian Children's Book Awards between 1945 - 1983 as its focus, because it encompassed the most prolific growth of fantasy-inspired, illustrated literature in Australia and • world-wide. The work of each illustrator selected for study either in storybook or picture book, is examined in the light of theatrical and artistic codes, illustrative traditions such as illusion and decoration, in terms of the relationships between text and illustration and the view of childhood and child readership. This study. has also used overseas literature as "benchmarks" for the criteria in examining these Australian works. This study shows that there has been a development in the way illustrators have dealt with the landscape, flora and fauna, people, Aboriginal mythology and the evocation and portrayal of Secondary Worlds. -

Australians All by Nadia Wheatley Illustrated by Ken Searle

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers Notes by Dr Robyn Sheahan-Bright Australians All by Nadia Wheatley Illustrated by Ken Searle ISBN 978 1 74114 637 0 Recommended for readers 9 yrs and older Older students and adults will also appreciate this book. These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ........................................... 2 Use in the curriculum ........................ 2 Layout of the Book ............................ 2 Before reading ........................................ 3 SOSE (Themes & Values) ......................... 4 Arts .............................................. 26 Language & Literacy ........................ 26 Visual Literacy ................................ 26 Creative Arts .................................. 26 Conclusion .......................................... 27 Bibliography of related texts ................... 27 Internet & film resources ....................... 29 About the writers .............................. ....30 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION ‘Historians sometime speak of our nation’s founding fathers and mothers, but it is the children of this country who – generation after generation – create and change our national identity.’ (p.241) In this significant -

The IBBY Honour List

The IBBY Honour List For this biennial list, National Sections of IBBY are invited to nominate outstanding recent books that are characteristic of their country and recommended for publication in different languages. One book can be nominated for each of the three categories: writing, illustration and translation. In 2016, for the first time IBBY Australia nominated a translator—John Nieuwenhuizen for Nine Open Arms. Writer: Emily Rodda—Rowan of Rin 1962 Writer: Nan Chauncy—Tangara 1996 1970 Writer: Patricia Wrightson—I Own the Illustrator: Peter Gouldthorpe—First Light Racecourse text by Gary Crew 1972 Writer: Colin Thiele—Blue Fin 1998 Writer: Peter Carey—The Big Bazoohley 1974 Writer: Ivan Southall—Josh Illustrator: John Winch—The Old Illustrator: Ted Greenwood—Joseph and Woman Who Loved to Read Lulu and the Prindiville House Pigeons 2000 Writer: Margaret Wild—First Day 1976 Writer: Patricia Wrightson—The Nargun and illustrations by Kim Gamble the Stars Illustrator: Graeme Base—The Worst Band Illustrator: Kilmeny & Deborah Niland— in the Universe Mulga Bill’s Bicycle by A.B. Paterson 2002 Writer: David Metzenthen—Stony Heart 1978 Writer: Eleanor Spence—The October Child Country Illustrator: Robert Ingpen—The Runaway Illustrator: Ron Brooks—Fox text by Punt text by Michael Page Margaret Wild 1980 Writer: Lilith Norman—A Dream of Seas 2004 Writer: Simon French—Where in the Illustrator: Percy Trezise and Dick World? Roughsey—The Quinkins Illustrator: Andrew McLean—A Year on Our 1982 Writer: Ruth Park—Playing Beatie Bow Farm text by Penny -

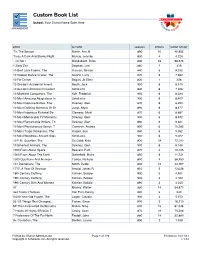

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Celebrating Great Australian Writing

FEATURE: CELEBRATING GREAT AUSTRALIAN WRITING CELEBRATING GREAT AUSTRALIAN WRITING First Tuesday Book Club The ABC First Tuesday Book Club's Jennifer Byrne was a terrific supporter J e n n i f e r ' s R eading Australia of the National Year of Reading 2012 and, in the last program of the series, on recom mendations 2 0 0 4 December, she announced the "10 While the First Tuesday Book Club Aussie Books You Should Read Before You The Lost M em ory of Skin, by Russell Banks. was looking for the top 10, the Copyright Die." A dark, magnificent study of Agency was thinking even bigger. The More than 20 000 people had voted America's underbelly, focusing on a Copyright Agency asked the Australian for the list and 500 000 viewers tuned 22-year old known only as "the Kid" who Society of Author's Council to come up in to watch the program and discover has committed a minor but unforgivable with a list of 200 classic Australian titles the final all-Australian reading list. crime and becomes part of the they thought students should encounter Jennifer told us, ‘[Booksellers] rang me community of the lost, living in a limbo- in school and university, as a special after the show saying they had had a world beneath a Florida causeway. ‘Reading Australia' initiative. huge response, and a number of books The Age of Miracles, by Karen Thompson The 200 titles include novels, short we'd mentioned had hit their top 10 Walker stories, drama, poetry, children's books, list overnight. -

The Children's Book Council of Australia Book of the Year Awards

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — CONTENTS Page BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — 1981 . 2 BOOK OF THE YEAR: OLDER READERS . .. 7 BOOK OF THE YEAR: YOUNGER READERS . 12 VISUAL ARTS BOARD AWARDS 1974 – 1976 . 17 BEST ILLUSTRATED BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 17 BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD: EARLY CHILDHOOD . 17 PICTURE BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 20 THE EVE POWNALL AWARD FOR INFORMATION BOOKS . 28 THE CRICHTON AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 32 CBCA AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 33 CBCA BOOK WEEK SLOGANS . 34 This publication © Copyright The Children’s Book Council of Australia 2021. www.cbca.org.au Reproduction of information contained in this publication is permitted for education purposes. Edited and typeset by Margaret Hamilton AM. CBCA Book of the Year Awards 1946 - 1 THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 – From 1946 to 1958 the Book of the Year Awards were judged and presented by the Children’s Book Council of New South Wales. In 1959 when the Children’s Book Councils in the various States drew up the Constitution for the CBC of Australia, the judging of this Annual Award became a Federal matter. From 1960 both the Book of the Year and the Picture Book of the Year were judged by the same panel. BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 1946 - 1981 Note: Until 1982 there was no division between Older and Younger Readers. 1946 – WINNER REES, Leslie Karrawingi the Emu John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham COMMENDED No Award 1947 No Award, but judges nominated certain books as ‘the best in their respective sections’ For Very Young Children: MASON, Olive Quippy Illus. -

PRESS RELEASE 29 January 2019 IBBY Australia Honour Books Annotated List 1962–2018

PRESS RELEASE 29 January 2019 IBBY Australia Honour Books Annotated List 1962–2018 IBBY Australia in partnership with the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature (NCACL) is proud to announce the release of the IBBY Australia Honour Books List 1962–2018. This ground-breaking publication presents 48 outstanding books, from Tangara (1962) to The Bone Sparrow and Teacup (2018). Annotations that succinctly place each book in its context, and biographical information about the writers and illustrators, add to the value of this unique resource. It is unique, in that while there are many booklists serving many purposes, this list has a specific tale to tell, the tale of IBBY Australia’s choice of these books, every two years forwarded to IBBY headquarters in Switzerland, to become part of a selection of books ‘characteristic of their country and suitable to recommend for publication in different languages’. In October 2018 IBBY Australia Inc and the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature (NCACL) launched an exhibition which opened in the Woden branch of Libraries ACT. The exhibition included copies of each of the IBBY Australia Honour Books, even those most elusive titles that had taken some sleuthing to track down, sitting on the shelves and inviting browsers to pick them up, to smile in recognition of old favourites and to explore those not encountered before. And alongside these Australian books was a collection, for the first time ever hosted in our country, of all the international IBBY Honour Books for 2018, its 191 books from 61 countries providing a snapshot of the best publications worldwide at this moment in time. -

Story Time: Australian Children's Literature

Story Time: Australian Children’s Literature The National Library of Australia in association with the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature 22 August 2019–09 February 2020 Exhibition Checklist Australia’s First Children’s Book Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Parliament Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Living Knowledge Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Bohrah the Kangaroo 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1453161 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Dinewan the Emu 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1458954 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) They Saw It Being Lifted from the Earth 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn2980282 1 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Tommy McRae (illustrator, c.1835–1901) Australian Legendary Tales: Folk-lore of the Noongahburrahs as Told to the Piccaninnies London: David Nutt; Melbourne: Melville, Mullen and Slade, 1896 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn995076 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Henrietta Drake-Brockman (selector and editor, 1901–1968) Elizabeth Durack (illustrator, 1915–2000) Australian Legendary Tales Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1953 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn2167373 Catherine Stow (K. -

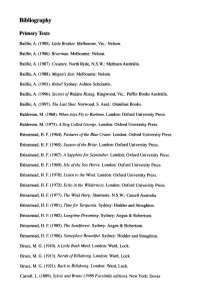

Bibliography Primary Texts

Bibliography Primary Texts Baillie, A. (1985). Little Brother. Melbourne, Vic: Nelson. Baillie, A. (1986). Riverman. Melbourne: Nelson. Baillie, A. (1987). Creature. North Ryde, N.S.W.: Methuen Australia. Baillie, A. (1988). Megan's Star. Melbourne: Nelson. Baillie, A. (1993). Rebel! Sydney: Ashton Scholastic. Baillie, A. (1996). Secrets ofWalden Rising. Ringwood, Vic: Puffin Books Australia. Baillie, A. (1997). The Last Shot. Norwood, S. Aust: Omnibus Books. Balderson, M. (1968). When Jays Fly to Barbmo. London: Oxford University Press. Balderson, M. (1975). A Dog Called George. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1964). Pastures of the Blue Crane. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1965). Season of the Briar. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1967). A Sapphire for September. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1969). Isle of the Sea Horse. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1970). Listen to the Wind. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1972). Echo in the Wilderness. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1977). The Wind Harp. Stanmore, N.S.W.: Cassell Australia. Brinsmead, H. F. (1981). Time for Tarquinia. Sydney: Hodder and Stoughton. Brinsmead, H. F. (1982). Longtime Dreaming. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Brinsmead, H. F. (1985). The Sandforest. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Brinsmead, H. F. (1986). Someplace Beautiful. Sydney: Hodder and Stoughton. Bruce, M. G. (1910). A Little Bush Maid. London: Ward, Lock. Bruce, M. G. (1913). Norah ofBillabong. London: Ward, Lock. Bruce, M. G. (1921). Back to Billabong. London: Ward, Lock. Carroll, L. (1889). Sylvie and Bruno (1988 Facsimile edition). New York: Dover Publications, Inc. Chauncy, N. -

Dancing on Coral Glenda Adams Introduced by Susan Wyndham The

Dancing on Coral Homesickness Glenda Adams Murray Bail Introduced by Susan Wyndham Introduced by Peter Conrad The True Story of Spit MacPhee Sydney Bridge Upside Down James Aldridge David Ballantyne Introduced by Phillip Gwynne Introduced by Kate De Goldi The Commandant Bush Studies Jessica Anderson Barbara Baynton Introduced by Carmen Callil Introduced by Helen Garner A Kindness Cup Between Sky & Sea Thea Astley Herz Bergner Introduced by Kate Grenville Introduced by Arnold Zable Reaching Tin River The Cardboard Crown Thea Astley Martin Boyd Introduced by Jennifer Down Introduced by Brenda Niall The Multiple Effects of Rainshadow A Difficult Young Man Thea Astley Martin Boyd Introduced by Chloe Hooper Introduced by Sonya Hartnett Drylands Outbreak of Love Thea Astley Martin Boyd Introduced by Emily Maguire Introduced by Chris Womersley classics_endmatter_2020.indd 1 14/1/20 5:29 pm When Blackbirds Sing The Dying Trade Martin Boyd Peter Corris Introduced by Chris Wallace-Crabbe Introduced by Charles Waterstreet The Australian Ugliness They’re a Weird Mob Robin Boyd Nino Culotta Introduced by Christos Tsiolkas Introduced by Jacinta Tynan The Life and Adventures of Aunts Up the Cross William Buckley Robin Dalton Introduced by Tim Flannery Introduced by Clive James The Dyehouse The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke Mena Calthorpe C. J. Dennis Introduced by Fiona McFarlane Introduced by Jack Thompson All the Green Year Careful, He Might Hear You Don Charlwood Sumner Locke Elliott Introduced by Michael McGirr Introduced by Robyn Nevin Fairyland -

BOOK CLUB SETS – January 2019 (35 Pages)

BOOK CLUB SETS – January 2019 (35 pages) □ 1788: the brutal truth of the first fleet – David Hill 392P On May 13th 1787 eleven ships sailed from Portsmouth destined for the colony of New South Wales where a penal settlement was to be established. David Hill tells of the politics behind the decision to transport convicts, the social conditions in Britain at the time, conditions on board the vessels, and what was involved in establishing penal colonies so distant from Britain. □ The 19th Wife – a novel – David Ebeshoff 514p Jordan returns from California to Utah to visit his mother in jail. As a teenager he was expelled from his family and religious community, a secretive Mormon offshoot sect. Now his father has been found shot dead in front of his computer, and one of his many wives - Jordan’s mother - is accused of the crime. Over a century earlier, Ann Eliza Young, the nineteenth wife of Brigham Young, Prophet and Leader of the Mormon Church, tells the sensational story of how her own parents were drawn into plural marriage, and how she herself battled for her freedom and escaped her powerful husband, to lead a crusade to end polygamy in the United States. Bold, shocking and gripping, The 19th Wife expertly weaves together these two narratives: a page turning literary mystery and an enthralling epic of love and faith. □ The 4 percent universe - Richard Panek. 297p In recent years, a handful of scientists has been racing to explain a disturbing aspect of our universe: only 4 percent of it consists of the matter that makes up you, me, and every star and planet.