Australian Children's Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ruth Park a Celebration

Ruth Park A CELEBRATION Ruth Park A Celebration Compiled and edited by Joy Hooton Friends of the National Library of Australia Canberra 1996 Acknowledgements All but one of the photographs in this volume were supplied by Ruth Park. The photograph facing page one was supplied by the Mitchell Library and is reproduced courtesy of the Australian Broadcasting Commission. Published with the assistance of Penguin Australia © Friends of the National Library of Australia National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Ruth Park : a celebration. Bibliography. ISBN 0 646 29461 X. 1. Park, Ruth. 2. Women novelists, Australian—20th century. 3. Novelists, Australian—20th century. I. Hooton, Joy W. (Joy Wendy), 1935- II. National Library of Australia. Friends. A823.3 Publisher's editor: Annabel Pengilley. Designer: Kathy Jakupec. Printer: Goanna Print, Canberra. Cover photograph by Wesley Stacey Contents Joy Hooton surveys Ruth Park's life and work 1 Michael King a fellow New Zealander pays tribute to Ruth Park's influence in the country of her birth 14 Elizabeth Riddell writes on A Fence around the Cuckcoo 15 Marcie Muir pays tribute to Ruth Park's writing for children and young adults 17 Marion Halligan writes on Ruth Park's novels: Some Sorcery in the Subconscious' 20 A Select Bibliography 28 Awards 33 Ruth Park, aged 26 Joy Hooton surveys Ruth Park's life and work Ruth Park was born in Auckland, New Zealand, the daughter of a pioneering bridge builder and road maker, whose work took his family into the wild territory of North Auckland and the King Country. As a result she had a singular early childhood, growing up as 'a forest creature', familiar with the New Zealand bush rather than with the products of civilisation or with children of her own age. -

Surprised by Joy: Children, Text and Identity

The Seventh Royale Ormsby Martin Lecture 2000 Surprised by Joy: Children, Text and Identity Maurice Saxby The Royale Ormsby Martin Lecture is administered by the Anglican Education Commission, Diocese of Sydney (a division of Anglican Youthworks) on behalf of the trustees: the Archbishop of Sydney, the Dean of Sydney and the Director of Education 1 Maurice Saxby Maurice Saxby, who was trained at Balmain Teacher’s College but went on to complete an Honours Degree in English from Sydney University as an evening student, believes passionately in the power of literature to enhance life, both for children and adults. He has taught infants, primary and secondary school students, but his career has been mainly as a lecturer in tertiary institutions. He retired as Head of the English Department at Kuring-gai College of Advanced Education. He has lectured extensively in children’s literature both in Australia and overseas including England, America, Germany, Japan and China. Maurice was the first National President of the Children’s Book Council of Australia and has served on judging panels for children’s literature many times in Australia; and he is the only Australian to have been selected as a juror for the prestigious international Hans Andersen Awards. He has received the Dromkeen Medal, the Lady Cutler Award and an Order of Australia for his services to children’s literature. Maurice’s publications range from academic works such as Offered to Children: A History of Australian Children’s Literature 1841–1941; Give them Wings: The Experience of Children’s Literature and Teaching Literature to Adolescents. -

Marjorie Barnard: a Re-Examination of Her Life and Work

Marjorie Barnard: a re-examination of her life and work June Owen A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales Australia School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Science Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Australia's Global UNSWSYDNEY University Surname/Family Name OWEN Given Name/s June Valerie Abbreviation for degree as give in the University calendar PhD Faculty Arts and Social Sciences School School of the Arts and Media Thesis Title Marjorie Barnard: a re-examination of her life and work Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) A wealth of scholarly works were written about Marjorie Barnard following the acclaim greeting the republication, in 1973, of The Persimmon Tree. That same year Louise E Rorabacher wrote a book-length study - Marjorie Barnard and M Barnard Eldershaw, after agreeing not to write about Barnard's private life. This led to many studies of the pair's joint literary output and short biographical studies and much misinformation, from scholars beguiled into believing Barnard's stories which were often deliberately disseminated to protect the secrecy of the affair that dominated her life between 1934 and 1942. A re-examination of her life and work is now necessary because there have been huge misunderstandings about other aspects of Barnard's life, too. Her habit of telling imaginary stories denigrating her father, led to him being maligned by his daughter's interviewers. Marjorie's commonest accusation was of her father's meanness, starting with her student allowance, but if the changing value of money is taken into account, her allowance (for pocket money) was extremely generous compared to wages of the time. -

Relationships to the Bush in Nan Chauncy's Early Novels for Children

Relationships to the Bush in Nan Chauncy’s Early Novels for Children SUSAN SHERIDAN AND EMMA MAGUIRE Flinders University The 1950s marked an unprecedented development in Australian children’s literature, with the emergence of many new writers—mainly women, like Nan Chauncy, Joan Phipson, Patricia Wrightson, Eleanor Spence and Mavis Thorpe Clark, as well as Colin Thiele and Ivan Southall. Bush and rural settings were strong favourites in their novels, which often took the form of a generic mix of adventure story and the bildungsroman novel of individual development. The bush provided child characters with unique challenges, which would foster independence and strength of character. While some of these writers drew on the earlier pastoral tradition of the Billabong books,1 others characterised human relationships to the land in terms of nature conservation. In the early novels of Chauncy and Wrightson, the children’s relationship to the bush is one of attachment and respect for the environment and its plants and creatures. Indeed these novelists, in depicting human relationships to the land, employ something approaching the strong Indigenous sense of ‘country’: of belonging to, and responsibility for, a particular environment. Later, both Wrightson and Chauncy turned their attention to Aboriginal presence, and the meanings which Aboriginal culture—and the bloody history of colonial race relations— gives to the land. In their earliest novels, what is strikingly original is the way both writers use bush settings to raise questions about conservation of the natural environment, questions which were about to become highly political. In Australia, the nature conservation movement had begun in the late nineteenth century, and resulted in the establishment of the first national parks. -

Ideas for Your Classroom Year 1–2

TEACHER RESOURCES IDEAS FOR YOUR CLASSROOM YEAR 1–2 MONDAY 3 MAY 2021 YEARS 1–2 MONDAY 03 THE UNDERCROFT MAY SUBIACO ARTS CENTRE SESSION: TAKING FLIGHT 9.50AM – 10.35AM CURRICULUM LINKS: The smallest of things can thrive, all we need English: personal responses to literature, narrative writing, is a little imagination, patience and belief - a visual language truth that lies at the heart of Fremantle writer Design & Technology: designing ideas Meg McKinlay’s beautiful picture book How to Science: physical science, forces Make a Bird. In this delightful exploration of creativity from a favourite local storyteller, Health: feelings Meg shares her own creative process, following General capabilities: creative and critical thinking an idea from the very start to the moment it takes form in the world, and encouraging you to do the same. SESSION: ANIMAL TALES CURRICULUM LINKS: 11.00AM – 11.45AM Helen Milroy is Australia’s first Cross-curricular priorities: Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Indigenous doctor, the 2021 Western Australian (ATSI) histories & culture of the Year and a descendant of the Palyku English: literature & context, language features, people. Crafted in the Australian Aboriginal responding to texts tradition of teaching stories, her books Science: biological science, Australian animals encompass stars, whales, birds and bugs, but Themes: personal strengths, friendship, hope, belonging the themes of strength and friendship shine History & Geography: ATSI people are connected to places the brightest. Join Helen in celebrating the wonderful characteristics of Australia’s native fauna. SESSION: EVERY STONE HAS A STORY 12.30PM – 1.15PM Join Mark Greenwood, award CURRICULUM LINKS: winning author of The Book of Stone for a hands-on exploration of nature’s wonders - English: responding to literature, evaluating texts, purpose & from crystals, to fossils that hold clues to the audience of texts prehistoric past, birthstones and gemstones, to Science: earth science - geology meteorites from Mars and beyond. -

Submission to the Productivity Commission Re Copyright Restrictions on the Parallel Importation of Books

SUBMISSION TO THE PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION RE COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS ON THE PARALLEL IMPORTATION OF BOOKS 14 January, 2009 As a peak Australian voluntary organisation whose membership represents authors, illustrators, publishers, booksellers, teachers, librarians, teacher-librarians and parents, the Children's Book Council of Australia would like to express its objection to changes to present provisions of the Copyright Act that restrict parallel importation. Australia has a vibrant book industry, including the publication of many books for children. We see these books as a major enculturating force – they help Australian children to discover and celebrate who we are and what is important to us; they tell us our own unique stories in our own language/s, asking us to critically examine ourselves and our way of life. Every year, in schools around Australia, tens of thousands of Australian children celebrate the best of Australian children's literature, culminating in the CBCA Book of the Year Awards followed by Book Week. Australian award-winning books are written by new as well as established authors. With some of these books, Australian publishers have taken a chance in their publication; a chance which may not have been taken if parallel importation restrictions had been lifted. Australian authors feature prominently in international awards and honour lists because of the high quality of their work. Before succeeding overseas, all of these authors have first been published by Australian publishers. Some (but not all) award- winning Australian -

A Writer's Calendar

A WRITER’S CALENDAR Compiled by J. L. Herrera for my mother and with special thanks to Rose Brown, Peter Jones, Eve Masterman, Yvonne Stadler, Marie-France Sagot, Jo Cauffman, Tom Errey and Gianni Ferrara INTRODUCTION I began the original calendar simply as a present for my mother, thinking it would be an easy matter to fill up 365 spaces. Instead it turned into an ongoing habit. Every time I did some tidying up out would flutter more grubby little notes to myself, written on the backs of envelopes, bank withdrawal forms, anything, and containing yet more names and dates. It seemed, then, a small step from filling in blank squares to letting myself run wild with the myriad little interesting snippets picked up in my hunting and adding the occasional opinion or memory. The beginning and the end were obvious enough. The trouble was the middle; the book was like a concertina — infinitely expandable. And I found, so much fun had the exercise become, that I was reluctant to say to myself, no more. Understandably, I’ve been dependent on other people’s memories and record- keeping and have learnt that even the weightiest of tomes do not always agree on such basic ‘facts’ as people’s birthdays. So my apologies for the discrepancies which may have crept in. In the meantime — Many Happy Returns! Jennie Herrera 1995 2 A Writer’s Calendar January 1st: Ouida J. D. Salinger Maria Edgeworth E. M. Forster Camara Laye Iain Crichton Smith Larry King Sembene Ousmane Jean Ure John Fuller January 2nd: Isaac Asimov Henry Kingsley Jean Little Peter Redgrove Gerhard Amanshauser * * * * * Is prolific writing good writing? Carter Brown? Barbara Cartland? Ursula Bloom? Enid Blyton? Not necessarily, but it does tend to be clear, simple, lucid, overlapping, and sometimes repetitive. -

Disenchantment: a Novel for Young Adults with a Discussion of Representations of Indigenous Australians and Native Americans in Books for Children and Young Adults

Disenchantment: a novel for young adults With a discussion of representations of Indigenous Australians and Native Americans in books for children and young adults Rebecca Louise Hazleden BA (hons), (Leeds) MA, (Leeds Metropolitan University) PhD, (Exon) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of English, Media Studies and Art History 1 Abstract This thesis is in two parts. The first is the creative project, a love story called Disenchantment, which is a speculative fiction novel for young adults. The novel consists of the testimony of an imprisoned girl, indigenous to a fictitious island, explaining how she has ended up in a prison cell condemned to hang for a murder she did not commit. As she relates her story to a visitor, a tale emerges of love and betrayal set against a backdrop of colonialism and violence. At first, Neka is an awkward and fearful little child, suckled by a half-dead mother and weaned by a bitter old Healer. The adults remark what a pity it is that the bright light of her mother was snuffed out by such a dull child. But then she is chosen as assistant to Elu, the beautiful and vibrant rebel girl from another clan, who is to be the new Healer. They embark on their training together, drawing closer, learning the secrets of the clan, healing the sick, talking to the dead, encountering the god of lightning, and awakening the god of spring. Neka starts to find her place in the world, and her love blossoms – love for her land, her people, and most of all for Elu. -

Apocalypse and Australian Speculative Fiction Roslyn Weaver University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2007 At the ends of the world: apocalypse and Australian speculative fiction Roslyn Weaver University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Weaver, Roslyn, At the ends of the world: apocalypse and Australian speculative fiction, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2007. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1733 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] AT THE ENDS OF THE WORLD: APOCALYPSE AND AUSTRALIAN SPECULATIVE FICTION A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ROSLYN WEAVER, BA (HONS) FACULTY OF ARTS 2007 CERTIFICATION I, Roslyn Weaver, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Roslyn Weaver 21 September 2007 Contents List of Illustrations ii Abstract iii Acknowledgments v Chapter One 1 Introduction Chapter Two 44 The Apocalyptic Map Chapter Three 81 The Edge of the World: Australian Apocalypse After 1945 Chapter Four 115 Exile in “The Nothing”: Land as Apocalypse in the Mad Max films Chapter Five 147 Children of the Apocalypse: Australian Adolescent Literature Chapter Six 181 The “Sacred Heart”: Indigenous Apocalypse Chapter Seven 215 “Slipstreaming the End of the World”: Australian Apocalypse and Cyberpunk Conclusion 249 Bibliography 253 i List of Illustrations Figure 1. -

The Development of Fantasy Illustration in Australian Children's Literature

The University of Tasmania "THE SHADOW LINE BETWEEN REALITY AND FANTASY": THE DEVELOPMENT OF FANTASY ILLUSTRATION IN AUSTRALIAN CHILDREN'S LITERATURE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Degree for Master of Education. Centre of Education by Irene Theresa Gray University of Tasmania December 1985. Acknowledgments I wish to thank the following persons for assistance in the presentation of this dissertation: - Mr. Hugo McCann, Centre for Education, University of Tasmania for his encouragement, time, assistance and critical readership of this document. Mr. Peter Johnston, librarian and colleague who kindly spent time in the word processing and typing stage. Finally my husband, Andrew whose encouragement and support ensured its completion. (i) ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to show that accompanying a development of book production and printing techniques in Australia, there has been a development in fantasy illustration in Australian children's literature. This study has identified the period of Australian Children's Book Awards between 1945 - 1983 as its focus, because it encompassed the most prolific growth of fantasy-inspired, illustrated literature in Australia and • world-wide. The work of each illustrator selected for study either in storybook or picture book, is examined in the light of theatrical and artistic codes, illustrative traditions such as illusion and decoration, in terms of the relationships between text and illustration and the view of childhood and child readership. This study. has also used overseas literature as "benchmarks" for the criteria in examining these Australian works. This study shows that there has been a development in the way illustrators have dealt with the landscape, flora and fauna, people, Aboriginal mythology and the evocation and portrayal of Secondary Worlds. -

Australians All by Nadia Wheatley Illustrated by Ken Searle

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers Notes by Dr Robyn Sheahan-Bright Australians All by Nadia Wheatley Illustrated by Ken Searle ISBN 978 1 74114 637 0 Recommended for readers 9 yrs and older Older students and adults will also appreciate this book. These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ........................................... 2 Use in the curriculum ........................ 2 Layout of the Book ............................ 2 Before reading ........................................ 3 SOSE (Themes & Values) ......................... 4 Arts .............................................. 26 Language & Literacy ........................ 26 Visual Literacy ................................ 26 Creative Arts .................................. 26 Conclusion .......................................... 27 Bibliography of related texts ................... 27 Internet & film resources ....................... 29 About the writers .............................. ....30 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION ‘Historians sometime speak of our nation’s founding fathers and mothers, but it is the children of this country who – generation after generation – create and change our national identity.’ (p.241) In this significant -

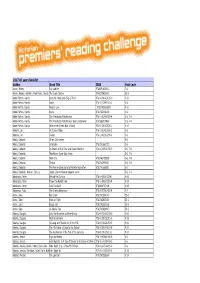

FINAL 2017 All Years Booklist.Xlsx

2017 All years Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Aaron, Moses Lily and Me 9780091830311 7-8 Aaron, Moses (reteller); Mackintosh, David (ill.)The Duck Catcher 9780733412882 EC-2 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 978-0-330-42185-0 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie 978-1-74299-010-1 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law : 9781742624280 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania 9781742990188 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker 978-1-86291-920-4 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker Goes Undercover 9781862919488 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 978-0-330-42526-1 9-10 Abdulla, Ian As I Grew Older 978-1-86291-183-3 5-6 Abdulla, Ian Tucker 978-1-86291-206-9 5-6 Abela, Deborah Ghost Club series 5-6 Abela, Deborah Grimsdon 9781741663723 5-6 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 978-1-74051-765-2 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Max Remy Super Spy series 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah New City 9781742758558 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Teresa 9781742990941 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Remarkable Secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen 9781741660951 5-6 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny Jasper Zammit Soccer Legend series 5-6, 7-8 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 978-1-4063-0029-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 978-1-4063-0028-4 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9780060737108 9-10 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Acton, Sara Ben Duck 9781741699142 EC-2 Acton, Sara Hold on Tight 9781742833491 EC-2 Acton, Sara Poppy Cat 9781743620168 EC-2 Acton, Sara As Big As You 9781743629697