Understanding CLL/SLL Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follicular Lymphoma

Follicular Lymphoma What is follicular lymphoma? Let us explain it to you. www.anticancerfund.org www.esmo.org ESMO/ACF Patient Guide Series based on the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines FOLLICULAR LYMPHOMA: A GUIDE FOR PATIENTS PATIENT INFORMATION BASED ON ESMO CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES This guide for patients has been prepared by the Anticancer Fund as a service to patients, to help patients and their relatives better understand the nature of follicular lymphoma and appreciate the best treatment choices available according to the subtype of follicular lymphoma. We recommend that patients ask their doctors about what tests or types of treatments are needed for their type and stage of disease. The medical information described in this document is based on the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) for the management of newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma. This guide for patients has been produced in collaboration with ESMO and is disseminated with the permission of ESMO. It has been written by a medical doctor and reviewed by two oncologists from ESMO including the lead author of the clinical practice guidelines for professionals, as well as two oncology nurses from the European Oncology Nursing Society (EONS). It has also been reviewed by patient representatives from ESMO’s Cancer Patient Working Group. More information about the Anticancer Fund: www.anticancerfund.org More information about the European Society for Medical Oncology: www.esmo.org For words marked with an asterisk, a definition is provided at the end of the document. Follicular Lymphoma: a guide for patients - Information based on ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines – v.2014.1 Page 1 This document is provided by the Anticancer Fund with the permission of ESMO. -

Circle) None Fever Night Sweats Wt Loss Laboratory Studies Hgb WBC Plate

LYMPHOMA STAGING DIAGRAM Instructions: boxed items must be completed History B Sx (Circle) none fever night sweats wt loss Laboratory studies Hgb WBC Plate ECOG performance status g/L x109/L x109/L LDH (patient/upper normal) / CERVICAL PRE-AURICULAR HIV antibody pos neg WALDEYER'S RING UPPER CERVICAL MEDIAN OR LOWER CERVICAL HBsAg pos neg POSTERIOR CERVICAL SUPRACLAVICULAR INFRACLAVICULAR MEDIASTINAL HBcoreAb pos neg PARATRACHEAL MEDIASTINAL AXILLARY Hep C Ab pos neg AXILLARY HILAR RETROCRURAL SPE monoclonal protein pos neg type____________ SPLEEN PARA AORTIC PARA AORTIC MESENTERIC For Hodgkin lymphoma only CELIAC COMMON ILIAC SPLENIC (HEPATIC) HILAR EXTERNAL ILIAC PORTAL Albumin g/L INGUINAL MESENTERIC Lymphs x 109/L INGUINAL FEMORAL OTHER EPITROCHLEAR POPLITEAL Treatment Largest tumor diameter (nearest whole cm) Treatment plan Initial biopsy site Date (d/m/y) / / Histologic diagnosis Doctor in Charge 1 _________________________________________ 2 Reason for referral Bone marrow pos neg not done New Recurrent Follow-up Completed by _______________ Date____________ List all other extranodal sites here 1 2 Complete if diagnosis or stage subsequently changed 3 4 Diagnosis/Stage amended to _________________________ 5 Reason__________________________________________ 6 By_______________________ Date______________ Stage (circle) 0 1 2 3 4 A B E This staging diagram can be found on NOTIFY PATIENT INFORMATION IF STAGE OR H:lym_docs\staging\lymphoma.doc DIAGNOSIS IS AMENDED Form #TH-41 Revised 26 March 2007 LYMPHOMA AND CHRONIC LYMPHOCYTIC LEUKEMIA STAGING SYSTEMS BCCA LYMPHOMA, HODGKIN AND CHRONIC LYMPHOCYTIC LEUKEMIA NON-HODGKIN 1982 STAGE FINDINGS STAGE INVOLVEMENT 0 Lymphocyte count > 5.0 x 109 /L 1 Single lymph node region (1) or one Bone marrow contains 40% extralymphatic site (1E). -

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Questions and Answers

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Questions and Answers What is Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma? Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is a cancer of the lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. When lymphocytes become cancerous (malignant), they multiply and become tumors. Lymphocytes are normally found in the blood stream and lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are found throughout the body and are identified by their location. They are a part of the body’s immune system, which includes the lymphatic system, spleen and lymphocytes. Some lymph nodes can be found just by feeling them in the neck, groin or under the arms. Some cannot be felt, but they can be seen on X-rays. NHL is the fifth most common cancer in the United States. Men are at slightly higher risk than women. It is more common in adults than children. The average age at diagnosis is 45 to 55 years. The cause of NHL remains unknown. What Are the Types and Symptoms of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma? There are more than 30 different types of NHL. The specific types of NHL are associated with different symptoms. Low-grade or indolent NHL is usually associated with painless swelling of lymph nodes (usually in the neck or over the collarbone), but patients are otherwise healthy. The swelling may go away for a while, but then return. If the low-grade NHL has spread outside of the lymph nodes, such as to the stomach, there may be discomfort in the affected area. Low-grade lymphomas grow slowly. Examples of low-grade NHLs include: Marginal zone lymphomas. -

MINI-REVIEW Large Cell Lymphoma Complicating Persistent Polyclonal B

Leukemia (1998) 12, 1026–1030 1998 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0887-6924/98 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/leu MINI-REVIEW Large cell lymphoma complicating persistent polyclonal B cell lymphocytosis J Roy1, C Ryckman1, V Bernier2, R Whittom3 and R Delage1 1Division of Hematology, 2Department of Pathology, Saint Sacrement Hospital, 3Division of Hematology, CHUQ, Saint Franc¸ois d’Assise Hospital, Laval University, Quebec City, Canada Persistent polyclonal B cell lymphocytosis (PPBL) is a rare immunoglobulin (Ig) M with a polyclonal pattern on protein lymphoproliferative disorder of unclear natural history and its electropheresis. Flow cytometry cell analysis displays the pres- potential for B cell malignancy remains unknown. We describe the case of a 39-year-old female who presented with stage IV- ence of the CD19 antigen and surface IgM with a normal B large cell lymphoma 19 years after an initial diagnosis of kappa/lambda ratio. In contrast to CLL, CD5 is absent. There PPBL; her disease was rapidly fatal despite intensive chemo- is an association between HLA-DR 7 and PPBL in more than therapy and blood stem cell transplantation. Because we had two-thirds of the patients but the reason for such an associ- recently identified multiple bcl-2/lg gene rearrangements in ation remains unclear.3,6 There has been one report of PPBL blood mononuclear cells of patients with PPBL, we sought evi- occurring in identical female twins.7 No other obvious genetic dence of this oncogene in this particular patient: bcl-2/lg gene rearrangements were found in blood mononuclear cells but not predisposition or familial inheritance has yet been described in lymphoma cells. -

Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Lymphoproliferative disorders Dr. Mansour Aljabry Definition Lymphoproliferative disorders Several clinical conditions in which lymphocytes are produced in excessive quantities ( Lymphocytosis) Lymphoma Malignant lymphoid mass involving the lymphoid tissues (± other tissues e.g : skin ,GIT ,CNS …) Lymphoid leukemia Malignant proliferation of lymphoid cells in Bone marrow and peripheral blood (± other tissues e.g : lymph nods ,spleen , skin ,GIT ,CNS …) Lymphoproliferative disorders Autoimmune Infection Malignant Lymphocytosis 1- Viral infection : •Infectious mononucleosis ,cytomegalovirus ,rubella, hepatitis, adenoviruses, varicella…. 2- Some bacterial infection: (Pertussis ,brucellosis …) 3-Immune : SLE , Allergic drug reactions 4- Other conditions:, splenectomy, dermatitis ,hyperthyroidism metastatic carcinoma….) 5- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) 6-Other lymphomas: Mantle cell lymphoma ,Hodgkin lymphoma… Infectious mononucleosis An acute, infectious disease, caused by Epstein-Barr virus and characterized by • fever • swollen lymph nodes (painful) • Sore throat, • atypical lymphocyte • Affect young people ( usually) Malignant Lymphoproliferative Disorders ALL CLL Lymphomas MM naïve B-lymphocytes Plasma Lymphoid cells progenitor T-lymphocytes AML Myeloproliferative disorders Hematopoietic Myeloid Neutrophils stem cell progenitor Eosinophils Basophils Monocytes Platelets Red cells Malignant Lymphoproliferative disorders Immature Mature ALL Lymphoma Lymphoid leukemia CLL Hairy cell leukemia Non Hodgkin lymphoma Hodgkin lymphoma T- prolymphocytic -

The Lymphoma Guide Information for Patients and Caregivers

The Lymphoma Guide Information for Patients and Caregivers Ashton, lymphoma survivor This publication was supported by Revised 2016 Publication Update The Lymphoma Guide: Information for Patients and Caregivers The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society wants you to have the most up-to-date information about blood cancer treatment. See below for important new information that was not available at the time this publication was printed. In November 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved obinutuzumab (Gazyva®) in combination with chemotherapy, followed by Gazyva alone in those who responded, for people with previously untreated advanced follicular lymphoma (stage II bulky, III or IV). In November 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris®) for treatment of adult patients with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (pcALCL) or CD30- expressing mycosis fungoides (MF) who have received prior systemic therapy. In October 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved acalabrutinib (CalquenceTM) for the treatment of adults with mantle cell lymphoma who have received at least one prior therapy. In October 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta™) for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after two or more lines of systemic therapy, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma. Yescarta is a CD19-directed genetically modified autologous T cell immunotherapy FDA approved. Yescarta is not indicated for the treatment of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. In September 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved copanlisib (AliqopaTM) for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) who have received at least two prior systemic therapies. -

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL)

Helpline (freephone) 0808 808 5555 [email protected] www.lymphoma-action.org.uk Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) This page is about anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), a type of T-cell lymphoma. On this page What is ALCL? Who gets it? Symptoms Treatment Relapsed and refractory ALCL Research and targeted treatments We have separate information about the topics in bold font. Please get in touch if you’d like to request copies or if you would like further information about any aspect of lymphoma. Phone 0808 808 5555 or email [email protected]. What is ALCL? Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a type of T-cell lymphoma – a non-Hodgkin lymphoma that develops from white blood cells called T cells. Under a microscope, the cancerous cells in ALCL look large, undeveloped and very abnormal (‘anaplastic’). There are four main types of ALCL. They have complicated names based on their features and the types of proteins they make: • ALK-positive ALCL (also known as ALK+ ALCL) is the most common type. In ALK-positive ALCL, the abnormal T cells have a genetic change (mutation) that means they make a protein called ‘anaplastic lymphoma kinase’ (ALK). In other words, they test positive for ALK. ALK-positive ALCL is a fast-growing (high-grade) lymphoma. Page 1 of 6 © Lymphoma Action • ALK-negative ALCL (also known as ALK- ALCL) is a high-grade lymphoma that accounts for around 3 in every 10 cases of ALCL. The abnormal T cells do not make the ALK protein – they test negative for ALK. -

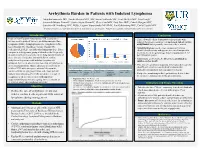

Arrhythmia Burden in Patients with Indolent Lymphoma

Arrhythmia Burden in Patients with Indolent Lymphoma Mujtaba Soniwala DO1, Saadia Sherazi MD1, MS, Susan Schleede MS1, Scott McNitt MS1, Tina Faugh2, Jeremiah Moore PharmD2, Justin Foster PharmD1, Clive Zent MD2, Paul Barr MD2, Patrick Reagan MD2, Jonathan W Friedberg MD2, MSSc, Eugene Storozynsky MD PhD1, Ilan Goldenberg MD1, Carla Casulo MD2 1Department of Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry; 2Wilmot Cancer Institute, University of Rochester Medical Center Introduction Results Conclusions Indolent Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) comprise a • This real-world cohort demonstrates that patients with heterogeneous group of diseases including marginal zone indolent lymphoma could have an increased risk of cardiac lymphoma (MZL), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL), arrhythmias that is possibly exacerbated by treatment. small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic • Atrial fibrillation was the most common arrhythmia leukemia (SLL/CLL), and follicular lymphoma (FL). These identified in this study and appears increased compared to compose a heterogenous group of disorders that frequently the incidence in the general age matched population (1-1.8 measures survival in years due to the long natural history of per 100 person-years). these diseases. Frequency and morbidity of cardiac • Surprisingly, of 80 deaths, 8 (10%) were attributed to arrhythmias in patients with indolent lymphoma is Arrhythmia Incidence Subtype of Indolent Lymphoma sudden cardiac death. unknown, but recent observations note that arrhythmias are • This data set contributes important information that can help an increasing problem. Due to advances in treatment for Arrhythmia incidence by CLL = 89 (53%) FL = 35 (21%) MZL = 27 (16%) LPL = 17 (10%) lymphoma subtype of total identify patients at increased risk of cardiovascular indolent NHL with emergence of novel therapeutics, (N = 168) Arrhythmia incidence Combination Targeted Therapy = Monoclonal Chemotherapy morbidity and mortality that can impact treatment. -

CD20-Negative Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphomas: Biology and Emerging Therapeutic Options

Expert Review of Hematology ISSN: 1747-4086 (Print) 1747-4094 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ierr20 CD20-negative diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: biology and emerging therapeutic options Jorge J Castillo, Julio C Chavez, Francisco J Hernandez-Ilizaliturri & Santiago Montes-Moreno To cite this article: Jorge J Castillo, Julio C Chavez, Francisco J Hernandez-Ilizaliturri & Santiago Montes-Moreno (2015) CD20-negative diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: biology and emerging therapeutic options, Expert Review of Hematology, 8:3, 343-354, DOI: 10.1586/17474086.2015.1007862 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/17474086.2015.1007862 Published online: 01 Feb 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 165 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ierr20 Download by: [North Shore Med Ctr], [Jorge Castillo] Date: 16 March 2016, At: 07:44 Review CD20-negative diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: biology and emerging therapeutic options Expert Rev. Hematol. 8(3), 343–354 (2015) Jorge J Castillo*1, CD20-negative diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a rare and heterogeneous group of Julio C Chavez2, lymphoproliferative disorders. Known variants of CD20-negative DLBCL include plasmablastic Francisco J lymphoma, primary effusion lymphoma, large B-cell lymphoma arising in human herpesvirus 8-associated multicentric Castleman disease and anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive DLBCL. Hernandez-Ilizaliturri3 Given the lack of CD20 expression, atypical cellular morphology and aggressive clinical and Santiago 4 behavior characterized by chemotherapy resistance and inferior survival rates, CD20-negative Montes-Moreno DLBCL represents a challenge from the diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives. -

Understanding Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/ Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma

Understanding Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/ Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) are forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that arise from B lymphocytes. CLL and SLL are essentially the same disease, with the only difference being the location where the cancer primarily occurs. When most of the cancer cells are located in the bloodstream and the bone marrow, the disease is referred to as CLL, although the lymph nodes and spleen are often involved. When the cancer cells are located mostly in the lymph nodes and are less frequent in the blood, the disease is called SLL. Many patients with CLL/SLL do not have any obvious symptoms of the disease. Their doctors might detect the disease during routine blood tests and/or a physical examination. For others, the disease is detected when symptoms occur and the patient goes to the doctor because he or she is worried, uncomfortable, or does not feel well. CLL/SLL may cause different symptoms depending on the location of the tumor in the body, including fatigue (extreme tiredness), shortness of breath, anemia (low red blood cell count), bruising easily, night sweats, weight loss, frequent infections. Other symptoms can include a swollen abdomen and feeling full even after eating only a small amount. However, many patients with CLL/SLL will live for years without symptoms. TREATMENT OPTIONS • Chlorambucil (Leukeran) and obinutuzumab (Gazyva) • Venetoclax (Venclexta) and obinutuzumab (Gazyva) Treatment is based on the severity of associated symptoms Occasionally patients might also be treated with chemotherapy, as well as the rate of cancer growth. -

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines® ) Non-Hodgkin’S Lymphomas Version 2.2015

NCCN Guidelines Index NHL Table of Contents Discussion NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines® ) Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas Version 2.2015 NCCN.org Continue Version 2.2015, 03/03/15 © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2015, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN® . Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2015 NCCN Guidelines Index NHL Table of Contents Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas Discussion DIAGNOSIS SUBTYPES ESSENTIAL: · Review of all slides with at least one paraffin block representative of the tumor should be done by a hematopathologist with expertise in the diagnosis of PTCL. Rebiopsy if consult material is nondiagnostic. · An FNA alone is not sufficient for the initial diagnosis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Subtypes included: · Adequate immunophenotyping to establish diagnosisa,b · Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), NOS > IHC panel: CD20, CD3, CD10, BCL6, Ki-67, CD5, CD30, CD2, · Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL)d See Workup CD4, CD8, CD7, CD56, CD57 CD21, CD23, EBER-ISH, ALK · Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), ALK positive (TCEL-2) or · ALCL, ALK negative > Cell surface marker analysis by flow cytometry: · Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) kappa/lambda, CD45, CD3, CD5, CD19, CD10, CD20, CD30, CD4, CD8, CD7, CD2; TCRαβ; TCRγ Subtypesnot included: · Primary cutaneous ALCL USEFUL UNDER CERTAIN CIRCUMSTANCES: · All other T-cell lymphomas · Molecular analysis to detect: antigen receptor gene rearrangements; t(2;5) and variants · Additional immunohistochemical studies to establish Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (See NKTL-1) lymphoma subtype:βγ F1, TCR-C M1, CD279/PD1, CXCL-13 · Cytogenetics to establish clonality · Assessment of HTLV-1c serology in at-risk populations. -

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL) and Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL)

Helpline (freephone) 0808 808 5555 [email protected] www.lymphoma-action.org.uk Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) This information is about chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). CLL and SLL are different forms of the same illness. They are often grouped together as a type of slow-growing (low-grade or indolent) non-Hodgkin lymphoma. On this page What is CLL/SLL? Who gets CLL? Symptoms of CLL Diagnosis and staging Outlook Treatment Follow-up Relapsed or refractory CLL Research and targeted treatments We have separate information about the topics in bold font. Please get in touch if you’d like to request copies or if you would like further information about any aspect of lymphoma. Phone 0808 808 5555 or email [email protected]. Page 1 of 13 © Lymphoma Action What is CLL/SLL? Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) are slow-growing types of blood cancer. They develop when white blood cells called lymphocytes grow out of control. Lymphocytes are part of your immune system. They travel around your body in your lymphatic system, helping you fight infections. There are two types of lymphocyte: T lymphocytes (T cells) and B lymphocytes (B cells). CLL and SLL are different forms of the same illness. They develop when B cells that don’t work properly build up in your body. • In CLL, the abnormal B cells build up in your blood and bone marrow. This is why it’s called ‘leukaemia’ – after ‘leucocytes’: the medical name for white blood cells.