Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRF4/DUSP22 Gene Rearrangement by FISH

IRF4/DUSP22 Gene Rearrangement by FISH The IRF4/DUSP22 locus is rearranged in a newly recognized subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement. These lymphomas are uncommon, but are clinically distinct from morphologically similar lymphomas, Tests to Consider including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade follicular lymphoma, and pediatric- type follicular lymphoma. The IRF4/DUSP22 locus is also rearranged in a subset of ALK- IRF4/DUSP22 (6p25) Gene Rearrangement negative anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCL), where this rearrangement is associated by FISH 3001568 with a signicantly better prognosis. Method: Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH) Test is useful in identifying ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphomas and large B- Disease Overview cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement The rearrangement is associated with an improved prognosis Incidence See Related Tests Large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement accounts for <1% of all non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas overall More common in younger patients, with an incidence of 5-6% under age 18 IRF4/DUSP22 rearrangement is found in 30% of ALK-negative ALCLs Symptoms/Findings Large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement typically presents with limited stage disease in the head and neck, while the presentation of ALK-negative ALCLs is variable. Disease-Oriented Information Patients with large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement typically have a favorable outcome after treatment. Rearrangement of the IRF4/DUSP22 locus in ALK-negative ALCL is associated with a better prognosis than ALK-negative ALCL without this rearrangement. Test Interpretation Analytical Sensitivity The limit of detection (LOD) for the IRF4/DUSP22 probe was established by calculating the upper limit of the abnormal signal pattern in normal cells using the Microsoft Excel BETAINV function. -

Follicular Lymphoma

Follicular Lymphoma What is follicular lymphoma? Let us explain it to you. www.anticancerfund.org www.esmo.org ESMO/ACF Patient Guide Series based on the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines FOLLICULAR LYMPHOMA: A GUIDE FOR PATIENTS PATIENT INFORMATION BASED ON ESMO CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES This guide for patients has been prepared by the Anticancer Fund as a service to patients, to help patients and their relatives better understand the nature of follicular lymphoma and appreciate the best treatment choices available according to the subtype of follicular lymphoma. We recommend that patients ask their doctors about what tests or types of treatments are needed for their type and stage of disease. The medical information described in this document is based on the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) for the management of newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma. This guide for patients has been produced in collaboration with ESMO and is disseminated with the permission of ESMO. It has been written by a medical doctor and reviewed by two oncologists from ESMO including the lead author of the clinical practice guidelines for professionals, as well as two oncology nurses from the European Oncology Nursing Society (EONS). It has also been reviewed by patient representatives from ESMO’s Cancer Patient Working Group. More information about the Anticancer Fund: www.anticancerfund.org More information about the European Society for Medical Oncology: www.esmo.org For words marked with an asterisk, a definition is provided at the end of the document. Follicular Lymphoma: a guide for patients - Information based on ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines – v.2014.1 Page 1 This document is provided by the Anticancer Fund with the permission of ESMO. -

Childhood Leukemia

Onconurse.com Fact Sheet Childhood Leukemia The word leukemia literally means “white blood.” fungi. WBCs are produced and stored in the bone mar- Leukemia is the term used to describe cancer of the row and are released when needed by the body. If an blood-forming tissues known as bone marrow. This infection is present, the body produces extra WBCs. spongy material fills the long bones in the body and There are two main types of WBCs: produces blood cells. In leukemia, the bone marrow • Lymphocytes. There are two types that interact to factory creates an overabundance of diseased white prevent infection, fight viruses and fungi, and pro- cells that cannot perform their normal function of fight- vide immunity to disease: ing infection. As the bone marrow becomes packed with diseased white cells, production of red cells (which ° T cells attack infected cells, foreign tissue, carry oxygen and nutrients to body tissues) and and cancer cells. platelets (which help form clots to stop bleeding) slows B cells produce antibodies which destroy and stops. This results in a low red blood cell count ° foreign substances. (anemia) and a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia). • Granulocytes. There are four types that are the first Leukemia is a disease of the blood defense against infection: Blood is a vital liquid which supplies oxygen, food, hor- ° Monocytes are cells that contain enzymes that mones, and other necessary chemicals to all of the kill foreign bacteria. body’s cells. It also removes toxins and other waste products from the cells. Blood helps the lymph system ° Neutrophils are the most numerous WBCs to fight infection and carries the cells necessary for and are important in responding to foreign repairing injuries. -

The Lymphoma and Multiple Myeloma Center

The Lymphoma and Multiple Myeloma Center What Sets Us Apart We provide multidisciplinary • Experienced, nationally and internationally recognized physicians dedicated exclusively to treating patients with lymphoid treatment for optimal survival or plasma cell malignancies and quality of life for patients • Cellular therapies such as Chimeric Antigen T-Cell (CAR T) therapy for relapsed/refractory disease with all types and stages of • Specialized diagnostic laboratories—flow cytometry, cytogenetics, and molecular diagnostic facilities—focusing on the latest testing lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic that identifies patients with high-risk lymphoid malignancies or plasma cell dyscrasias, which require more aggresive treatment leukemia, multiple myeloma and • Novel targeted therapies or intensified regimens based on the other plasma cell disorders. cancer’s genetic and molecular profile • Transplant & Cellular Therapy program ranked among the top 10% nationally in patient outcomes for allogeneic transplant • Clinical trials that offer tomorrow’s treatments today www.roswellpark.org/partners-in-practice Partners In Practice medical information for physicians by physicians We want to give every patient their very best chance for cure, and that means choosing Roswell Park Pathology—Taking the best and Diagnosis to a New Level “ optimal front-line Lymphoma and myeloma are a diverse and heterogeneous group of treatment.” malignancies. Lymphoid malignancy classification currently includes nearly 60 different variants, each with distinct pathophysiology, clinical behavior, response to treatment and prognosis. Our diagnostic approach in hematopathology includes the comprehensive examination of lymph node, bone marrow, blood and other extranodal and extramedullary tissue samples, and integrates clinical and diagnostic information, using a complex array of diagnostics from the following support laboratories: • Bone marrow laboratory — Francisco J. -

Late Effects Among Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Acute Leukemia in the Netherlands: a Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group Report

0031-3998/95/3805-0802$03.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 38, No.5, 1995 Copyright © 1995 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in U.S.A. Late Effects among Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Acute Leukemia in The Netherlands: A Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group Report A. VAN DER DOES-VAN DEN BERG, G. A. M. DE VAAN, J. F. VAN WEERDEN, K. HAHLEN, M. VAN WEEL-SIPMAN, AND A. J. P. VEERMAN Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group,' The Hague, The Netherlands A.8STRAC ' Late events and side effects are reported in 392 children cured urogenital, or gastrointestinal tract diseases or an increased vul of leukemia. They originated from 1193 consecutively newly nerability of the musculoskeletal system was found. However, diagnosed children between 1972 and 1982, in first continuous prolonged follow-up is necessary to study the full-scale late complete remission for at least 6 y after diagnosis, and were effects of cytostatic treatment and radiotherapy administered treated according to Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group during childhood. (Pediatr Res 38: 802-807, 1995) protocols (70%) or institutional protocols (30%), all including cranial irradiation for CNS prophylaxis. Data on late events (relapses, death in complete remission, and second malignancies) Abbreviations were collected prospectively after treatment; late side effects ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia were retrospectively collected by a questionnaire, completed by ANLL, acute nonlymphocytic leukemia the responsible pediatrician. The event-free survival of the 6-y CCR, continuous first complete remission survivors at 15 y after diagnosis was 92% (±2%). Eight late DCLSG, Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group relapses and nine second malignancies were diagnosed, two EFS, event free survival children died in first complete remission of late toxicity of HR, high risk treatment, and one child died in a car accident. -

Quantitative Analysis of Bcl-2 Expression in Normal and Leukemic Human B-Cell Differentiation

Leukemia (2004) 18, 491–498 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0887-6924/04 $25.00 www.nature.com/leu Quantitative analysis of bcl-2 expression in normal and leukemic human B-cell differentiation P Menendez1,2, A Vargas3, C Bueno1,2, S Barrena1,2, J Almeida1,2 M de Santiago1,2,ALo´pez1,2, S Roa2, JF San Miguel2,4 and A Orfao1,2 1Servicio General de Citometrı´a, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain; 2Departamento de Medicina and Centro de Investigacio´n del Ca´ncer, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain; 3Servicio de Inmunodiagno´stico, Departamento de Patologı´a Clı´nica, Hospital Nacional Edgardo Rebagliati Martins, Lima, Peru´, ; and 4Servicio de Hematologı´a, Hospital Universitario, Salamanca, Spain Lack of apoptosis has been linked to prolonged survival of results in the overexpression of the bcl-2 protein and it malignant B cells expressing bcl-2. The aim of the present represented the first clear example of a common step in study was to analyze the amount of bcl-2 protein expressed 9,10 along normal human B-cell maturation and to establish the oncogenesis mediated by decreased cell death. Currently, frequency of aberrant bcl-2 expression in B-cell malignancies. the exact antiapoptotic pathways through which bcl-2 exerts its In normal bone marrow (n ¼ 11), bcl-2 expression obtained by role are only partially understood, involving decreased mito- quantitative multiparametric flow cytometry was highly vari- chondrial release of cytochrome c, which in turn is required for þ À able: very low in both CD34 and CD34 B-cell precursors, high the activation of procaspase-9 and the subsequent initiation of in mature B-lymphocytes and very high in plasma cells. -

Health | Childhood Cancer America's Children and the Environment

Health | Childhood Cancer Childhood Cancer Cancer is not a single disease, but includes a variety of malignancies in which abnormal cells divide in an uncontrolled manner. These cancer cells can invade nearby tissues and can migrate by way of the blood or lymph systems to other parts of the body.1 The most common childhood cancers are leukemias (cancers of the white blood cells) and cancers of the brain or central nervous system, which together account for more than half of new childhood cancer cases.2 Cancer in childhood is rare compared with cancer in adults, but still causes more deaths than any factor, other than injuries, among children from infancy to age 15 years.2 The annual incidence of childhood cancer has increased slightly over the last 30 years; however, mortality has declined significantly for many cancers due largely to improvements in treatment.2,3 Part of the increase in incidence may be explained by better diagnostic imaging or changing classification of tumors, specifically brain tumors.4 However, the President’s Cancer Panel recently concluded that the causes of the increased incidence of childhood cancers are not fully understood, and cannot be explained solely by the introduction of better diagnostic techniques. The Panel also concluded that genetics cannot account for this rapid change. The proportion of this increase caused by environmental factors has not yet been determined.5 The causes of cancer in children are poorly understood, though in general it is thought that different forms of cancer have different causes. According to scientists at the National Cancer Institute, established risk factors for the development of childhood cancer include family history, specific genetic syndromes (such as Down syndrome), high levels of radiation, and certain pharmaceutical agents used in chemotherapy.4,6 A number of studies suggest that environmental contaminants may play a role in the development of childhood cancers. -

Curing Childhood Leukemia, October 1997

This article was published in 1997 and has not been updated or revised. CURING CHILDHOOD LEUKEMIA ancer is an insidious disease. The culprit is not bacterial infections, viral infections, and many other a foreign invader, but the altered descendants illnesses. _) of our own cells, which reproduce uncontrol The fight against cancer has been more of a war of lably. In this civil war, it is hard to distinguish friend attrition than a series of spectacular, instantaneous vic from foe, to tat;get the cancer cells without killing the tories, and the research into childhood leukemia over the healthy cells. Most of our current cancer therapies, last 40 years is no exception. But most of the children who including the cure for childhood leukemia described here, are victims of this disease can now be cured, and the are based on the fact that cancer cells reproduce without drugs that made this possible are the antimetabolite some of the safeguards present in normal cells. If we can drugs that will be described here. The logic behind those interfere with cell reproduction, the cancer cells will be drugs came from a wide array of research that defined hit disproportionately hard and often will not recover. the chemical workings of the cell--research done by scien The scientists and physicians who devised the cure for tists who could not know that their findings would even childhood leukemia pioneered a rational approach to tually save the lives of up to thirty thousand children in destroying cancer cells, using knowledge about the cell the United States. -

Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Lymphoproliferative disorders Dr. Mansour Aljabry Definition Lymphoproliferative disorders Several clinical conditions in which lymphocytes are produced in excessive quantities ( Lymphocytosis) Lymphoma Malignant lymphoid mass involving the lymphoid tissues (± other tissues e.g : skin ,GIT ,CNS …) Lymphoid leukemia Malignant proliferation of lymphoid cells in Bone marrow and peripheral blood (± other tissues e.g : lymph nods ,spleen , skin ,GIT ,CNS …) Lymphoproliferative disorders Autoimmune Infection Malignant Lymphocytosis 1- Viral infection : •Infectious mononucleosis ,cytomegalovirus ,rubella, hepatitis, adenoviruses, varicella…. 2- Some bacterial infection: (Pertussis ,brucellosis …) 3-Immune : SLE , Allergic drug reactions 4- Other conditions:, splenectomy, dermatitis ,hyperthyroidism metastatic carcinoma….) 5- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) 6-Other lymphomas: Mantle cell lymphoma ,Hodgkin lymphoma… Infectious mononucleosis An acute, infectious disease, caused by Epstein-Barr virus and characterized by • fever • swollen lymph nodes (painful) • Sore throat, • atypical lymphocyte • Affect young people ( usually) Malignant Lymphoproliferative Disorders ALL CLL Lymphomas MM naïve B-lymphocytes Plasma Lymphoid cells progenitor T-lymphocytes AML Myeloproliferative disorders Hematopoietic Myeloid Neutrophils stem cell progenitor Eosinophils Basophils Monocytes Platelets Red cells Malignant Lymphoproliferative disorders Immature Mature ALL Lymphoma Lymphoid leukemia CLL Hairy cell leukemia Non Hodgkin lymphoma Hodgkin lymphoma T- prolymphocytic -

The Lymphoma Guide Information for Patients and Caregivers

The Lymphoma Guide Information for Patients and Caregivers Ashton, lymphoma survivor This publication was supported by Revised 2016 Publication Update The Lymphoma Guide: Information for Patients and Caregivers The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society wants you to have the most up-to-date information about blood cancer treatment. See below for important new information that was not available at the time this publication was printed. In November 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved obinutuzumab (Gazyva®) in combination with chemotherapy, followed by Gazyva alone in those who responded, for people with previously untreated advanced follicular lymphoma (stage II bulky, III or IV). In November 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris®) for treatment of adult patients with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (pcALCL) or CD30- expressing mycosis fungoides (MF) who have received prior systemic therapy. In October 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved acalabrutinib (CalquenceTM) for the treatment of adults with mantle cell lymphoma who have received at least one prior therapy. In October 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta™) for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after two or more lines of systemic therapy, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma. Yescarta is a CD19-directed genetically modified autologous T cell immunotherapy FDA approved. Yescarta is not indicated for the treatment of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. In September 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved copanlisib (AliqopaTM) for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) who have received at least two prior systemic therapies. -

Antibody Drug Conjugates in Lymphoma

Review: Clinical Trial Outcomes Nathwani & Chen Antibody drug conjugates in lymphoma 6 Review: Clinical Trial Outcomes Antibody drug conjugates in lymphoma Clin. Investig. (Lond.) Antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) are comprised of monoclonal antibodies physically Nitya Nathwani1 & Robert linked to cytotoxic molecules. They expressly target cancer cells by delivering cytotoxic Chen*,1 agents to cells displaying specific antigens, and minimize damage to normal tissue. The 1Department of Hematology & Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, City efficacy and tolerability of these agents are primarily determined by the target antigen, of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA the cytotoxic agent and the linker connecting the cytotoxic agent to the monoclonal *Author for correspondence: antibody. Following advances in technology, clinical trials have demonstrated greater Tel.: +626 256 4673 (ext. 65298) efficacy for ADCs compared with the corresponding naked monoclonal antibodies. Fax: +626 301 8116 This review summarizes the features of current clinically active ADCs in lymphoma and [email protected] emphasizes recent clinical data elucidating the benefit of antibody-directed delivery of cytotoxic agents to tumor cells. Keywords: antibody drug conjugates • lymphoma • monoclonal antibodies Lymphoma is the most common hematologic concentration and poor performance status malignancy, and is subdivided into two main are adverse prognostic factors. SEER (Sur- types: Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non- veillance, Epidemiology and End Results) Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). In the United data from the National Cancer Institute, States, there are an estimated 731,277 people 2013 has revealed a significant improvement 10.4155/CLI.14.73 living with or in remission from lymphoma. in survival rates in this group of diseases in In 2013, there were an estimated 79,030 new the last four decades. -

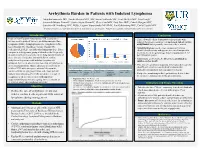

Arrhythmia Burden in Patients with Indolent Lymphoma

Arrhythmia Burden in Patients with Indolent Lymphoma Mujtaba Soniwala DO1, Saadia Sherazi MD1, MS, Susan Schleede MS1, Scott McNitt MS1, Tina Faugh2, Jeremiah Moore PharmD2, Justin Foster PharmD1, Clive Zent MD2, Paul Barr MD2, Patrick Reagan MD2, Jonathan W Friedberg MD2, MSSc, Eugene Storozynsky MD PhD1, Ilan Goldenberg MD1, Carla Casulo MD2 1Department of Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry; 2Wilmot Cancer Institute, University of Rochester Medical Center Introduction Results Conclusions Indolent Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) comprise a • This real-world cohort demonstrates that patients with heterogeneous group of diseases including marginal zone indolent lymphoma could have an increased risk of cardiac lymphoma (MZL), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL), arrhythmias that is possibly exacerbated by treatment. small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic • Atrial fibrillation was the most common arrhythmia leukemia (SLL/CLL), and follicular lymphoma (FL). These identified in this study and appears increased compared to compose a heterogenous group of disorders that frequently the incidence in the general age matched population (1-1.8 measures survival in years due to the long natural history of per 100 person-years). these diseases. Frequency and morbidity of cardiac • Surprisingly, of 80 deaths, 8 (10%) were attributed to arrhythmias in patients with indolent lymphoma is Arrhythmia Incidence Subtype of Indolent Lymphoma sudden cardiac death. unknown, but recent observations note that arrhythmias are • This data set contributes important information that can help an increasing problem. Due to advances in treatment for Arrhythmia incidence by CLL = 89 (53%) FL = 35 (21%) MZL = 27 (16%) LPL = 17 (10%) lymphoma subtype of total identify patients at increased risk of cardiovascular indolent NHL with emergence of novel therapeutics, (N = 168) Arrhythmia incidence Combination Targeted Therapy = Monoclonal Chemotherapy morbidity and mortality that can impact treatment.