Sri Lanka About This Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Ethnic Crisis and Newspaper Media Performance in Sri Lanka (Related to Selected Newspaper Media from April of 1983 to September of 1983)

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 1, Ver. 8 (January. 2018) PP 25-33 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org A Study on Ethnic Crisis and Newspaper Media performance in Sri Lanka (Related to selected Newspaper media from April of 1983 to September of 1983) Assistant Lecturer Sarasi Chaya Bandara Department of Political Science University of Kelaniya Kelaniya Corresponding Author: Assistant Lecturer Sarasi Chaya Bandara Abstract: The strong contribution denoted by media, in order to create various psychological printings to contemporary folk consciousness within a chaotic society which is consist of an ethnic conflict is extremely unique. Knowingly or unknowingly media has directly influenced on intensification of ethnic conflict which was the greatest calamity in the country inherited to a more than three decades history. At the end of 1970th decade, the newspaper became as the only media which is more familiar and which can heavily influence on public. The incident that the brutal murder of 13 military officers becoming victims of terrorists on 23rd of 1983 can be identified as a decisive turning point within the ethnic conflict among Sinhalese and Tamils. The local newspaper reporting on this case guided to an ethnical distance among Sinhalese and Tamils. It is expected from this investigation, to identify the newspaper reporting on the case of assassination of 13 military officers on 23rd of July 1983 and to investigate whether that the government and privet newspaper media installations manipulated their own media reporting accordingly to professional ethics and media principles. The data has investigative presented based on primary and secondary data under the case study method related with selected newspapers published on July of 1983, It will be surely proven that journalists did not acted to guide the folk consciousness as to grow ethnical cordiality and mutual trust. -

International Migration in the Americas

INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION IN THE AMERICAS SICREMI 2012 Organization of American States Organization of American States INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION IN THE AMERICAS Second Report of the Continuous Reporting System on International Migration in the Americas (SICREMI) 2012 OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data International Migration in the Americas: Second Report of the Continuous Reporting System on International Migration in the Americas (SICREMI) 2012. p.; cm. Includes bibliographical references. (OEA Documentos Oficiales; OEA Ser.D) (OAS Official Records Series; OEA Ser.D) ISBN 978-0-8270-5927-6 1. Emigration and immigration--Economic aspects. 2. Emigration and immigration--Social aspects. 3. Emigration and im- migration law. 4. Alien labor. 5. Refugees. I. Organization of American States. Department of Social Development and Employment. Migration and Development Program (MIDE). II. Continuous Reporting System on International Migration in the Americas (SICREMI). III. Title: Second Report of the Continuous Reporting System on International Migration in the Americas (SICREMI) 2012. IV. Series. OEA/Ser.D/XXVI.2.2 ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES 17th Street and Constitution Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006, USA www.oas.org All rights reserved. Secretary General, OAS José Miguel Insulza Assistant Secretary General, OAS Albert R. Ramdin Executive Secretary for Integral Development Sherry Tross Director, Department of Social Development and Employment Ana Evelyn Jacir de Lovo The partial or complete reproduction of this document without previous authorization could result in a violation of the applicable law. The Department of Social Development and Employment supports the dissemination of this work and will normally authorize permission for its reproduction. To request permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this publication, please send a request to: Department of Social Development and Employment Organization of American States 1889 F ST N.W. -

Sri Lanka Welcomes the 950,000Th Tourist to the Island

Sri Lanka welcomes the 950,000th tourist to the island Heralding the news of a prosperous future for Sri Lanka Tourism, the 950,000th tourist was warmly welcomed by a group including His Excellency Udayanga Weerathunga, the Sri Lankan Ambassador to Russia, Mr. Rumy Jauffer, the Managing Director of SLTPB, Mr.S. Shanthi Kumar, Vice President of Sri Lanka Tourist Hoteliers Association and Mr.Mervi Fernandopulle, Past President of Association of Small and Medium Enterprises at Bandaranaike International Airport on December 18 at a special ceremony. Mr. Krzysztof Kujawa and Ms. Agata Dziekn were given special gifts for being the lucky couple from Poland to pass the milestone, so that their next stay in Sri Lanka will be absolutely free. This is the first time ever that a number of 950,000 tourists, the target of Sri Lanka Tourism for the year 2012, arrived in Sri Lanka. In the month of November,2012 the total number of tourist arrival figure was 109,202; the highest number of tourists ever turned up within a single month in the Sri Lanka Tourism History. It indicates a 20% growth compared to the previous year. Having identified Russia, Eastern Europe Countries, Japan, China, Korea and India as emerging markets the SLTPB executed a new series of promotional activities incorporating the new strategies of the government. This campaign included travel fairs, roadshows, major advertising campaigns and social media promotions. The said campaign resulted in a greater contribution from the aforesaid countries. Also, today the involvement of a number of small and medium enterprises in the tourism industry has helped earn a lot of foreign exchange. -

The Impact of Drought: a Study Based on Anuradhapra District in Sri Lanka Kaleel.MIM1, Nijamir.K2

International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology (IJEAB) Vol-2, Issue-4, July -Aug- 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijeab/2.4.87 ISSN: 2456-1878 The Impact of Drought: A Study Based on Anuradhapra District in Sri Lanka Kaleel.MIM1, Nijamir.K2 Department of Geography, South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Oluvil Abstract— Anuradhapura District being one of the paddy in Anuradhapura Districts: Horovapothana, Ipolagama, providers in Sri Lanka highly affected due to the drought Nuwaragampalatha, Rambewa, Thirappana, disaster. The trend and cause for the drought should be Nachchathuwa, Palugaswewa, Kekirawa, identified for future remedial measures. Thus this study is Kahalkasthikiliya, Thambuthegama, Pathaviya, conducted based on the following objective. The primary Madavachchi and Kepatikollawa are the Divisional objective is that ‘identifying the impact of drought in Secretariats, highly affected. Anuradhapura District’ and the secondary objective are The impact of the drought occurrence should be ‘finding the direct and indirect factors causing drought controlled to pave a way for the agriculture and for the and the influence of drought in agriculture in the study socio economic development of inhabitants in area and proposing suggestions to lessen the impact of Anuradhapura. drought in the study area. To attain these objectives data from 1900 to 2014 were collected. All the data were II. STUDY AREA analysed and the trend of drought, condition of drought Anuradhpura District is situated in the dry zone of Sri and the impact of drought were identified. Many Lanka in the north central province of Sri Lanka. It has 22 suggestions have been provided in the suggestion part. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

The Entrenchment of Sinhalese Nationalism in Post-War Sri Lanka by Anne Gaul

An Opportunity Lost The Entrenchment of Sinhalese Nationalism in Post-war Sri Lanka by Anne Gaul Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervised by: Dr. Andrew Shorten Submitted to the University of Limerick, November 2016 Abstract This research studies the trajectory of Sinhalese nationalism during the presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa from 2005 to 2015. The role of nationalism in the protracted conflict between Sinhalese and Tamils is well understood, but the defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in 2009 has changed the framework within which both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalism operated. With speculations about the future of nationalism abound, this research set out to address the question of how the end of the war has affected Sinhalese nationalism, which remains closely linked to politics in the country. It employs a discourse analytical framework to compare the construction of Sinhalese nationalism in official documents produced by Rajapaksa and his government before and after 2009. A special focus of this research is how through their particular constructions and representations of Sinhalese nationalism these discourses help to reproduce power relations before and after the end of the war. It argues that, despite Rajapaksa’s vociferous proclamations of a ‘new patriotism’ promising a united nation without minorities, he and his government have used the momentum of the defeat of the Tamil Tigers to entrench their position by continuing to mobilise an exclusive nationalism and promoting the revival of a Sinhalese-dominated nation. The analysis of history textbooks, presidential rhetoric and documentary films provides a contemporary empirical account of the discursive construction of the core dimensions of Sinhalese nationalist ideology. -

Final Report Nnd Minutes

WHO Regional Committee for South-East Asia final Report nnd Minutes Fortieth Session, Pyongyang, DPR Korea 15-21 Sep~ember1987 WORLD HEALTH 0RG.t-NEZATION Regional Offic; for South-East Asia New Delhi, No ember 1985 -. WHO Regional Committee for South-East Asia Final Report and Minutes Fortieth Session, Pyongyang, DPR Korea 15-21 September 1987 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Regional Office for South-East Asia New Delhi, November 1987 CONTENTS Page SECTION I - REPORT OF THE REGIONAL COMMITTEE INTRODUCTION PART I - RESOLUTIONS SEA/RC~O/RL Prevention and Control of AIDS in the South-East Asia Region SEA/RC~O/R~ Management of WHO'S Resources SEA/RC~O/R~ Information and Education for Health in Support of Health for All by the Year 2000 SEA/RC~~/R~Targeting for Reorientation of Medical Education for Health Manpower Development in the Context of Achieving Health for All by the Year 2000 sEA/Rc~O/R~ Intensification of PHC Through District Health Systems Towards Achieving Health for All by the Year 2000 SEA/RC~O/R~Method of Appointment of the Regional Director sEA/Rc~O/R~Thirty-ninth Annual Report of the Regional Director sEA/Rc~O/RB Selection of a Topic for Technical Discussions a. SEA/RCLO/R~ Resolution of Thanks sEA/R~40/R10 Time and Place of Forty-first and Forty-second Sessions s~A/RC40/Rll Detailed Programme Budget for 1988-1989 and Report of the Sub-Committee on Programme Budget Page v PART I1 - DISCUSSION ON THE THIRTY-NINTH AlRmAL REPORT OF THE REGIONAL DIRECTOR PART I11 - EXAMINATION OF THE DETAILED PROGR4KME BUDGET FOR 1988-1989 PART IV - DISCUSSION ON OTHER MATTERS Item 1. -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

Genesis of Stupas

Genesis of Stupas Shubham Jaiswal1, Avlokita Agrawal2 and Geethanjali Raman3 1, 2 Indian Institue of Technology, Roorkee, India {[email protected]} {[email protected]} 3 Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology, Ahmedabad, India {[email protected]} Abstract: Architecturally speaking, the earliest and most basic interpretation of stupa is nothing but a dust burial mound. However, the historic significance of this built form has evolved through time, as has its rudimentary structure. The massive dome-shaped “anda” form which has now become synonymous with the idea of this Buddhist shrine, is the result of years of cultural, social and geographical influences. The beauty of this typology of architecture lies in its intricate details, interesting motifs and immense symbolism, reflected and adapted in various local contexts across the world. Today, the word “stupa” is used interchangeably while referring to monuments such as pagodas, wat, etc. This paper is, therefore, an attempt to understand the ideology and the concept of a stupa, with a focus on tracing its history and transition over time. The main objective of the research is not just to understand the essence of the architectural and theological aspects of the traditional stupa but also to understand how geographical factors, advances in material, and local socio-cultural norms have given way to a much broader definition of this word, encompassing all forms, from a simplistic mound to grand, elaborate sanctums of great value to architecture and society -

A Study About the Cognomens That Were Adopted by the Kings During Anuradhapura Era

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 10, Issue 1, January 2020 153 ISSN 2250-3153 A Study about the cognomens that were adopted by the kings during Anuradhapura Era Professor Anurin Indika Diwakara Department of Sinhala, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.10.01.2020.p9723 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.10.01.2020.p9723 Abstract: During the Anuradhapura Era the King was the head of the state. When studying inscription stones enlisted in this regard, what is clearly visible is the fact that, a reign based on heritance has been functioning. The kingship was deserved by those who hail from the Kshathriya dynasty. The amateur prince becomes a proper king after the coronation ceremony. In the absence of such coronation, the prince is not considered as the king of the state. In Mahavamsa Teeka, this is discussed at length. The one who commanded the entire governance system was the King, thus since the inception, a governance based on dynastic line was existed in ancient Sri Lanka. (Journal of the Royal Artistic Society of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1936, p.443.) Corpus Sri Lanka was so closely and intimately connected with India that every great change that took place in the main continent whether political, social, economic or religious influenced considerably the life of the people of Sri Lanka (Amaratunga G & Gunawardana N, 2019, Volume-3-issue6, 203-206). The king needs to be a secular, orderly person in his governance due to certain factors; those were to receive rain at apt time in favor of successful cultivation, to obtain prosperity and blessing for both citizens and the state, and for the smooth function of his governance with the help of citizens. -

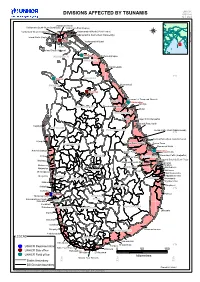

DIVISIONS AFFECTED by TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka

UNHCR DIVISIONS AFFECTED BY TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka ValikamamValikamam NorthNorth ValikamamValikamam South-WestSouth-West (Sandilipay)(Sandilipay) ValikamamValikamam EastEast (Kopay)(Kopay) Valikamam West (Chankanai) VadamaradchiVadamaradchi NorthNorth (Point(Point Perdro)Perdro) JAFFNAJAFFNA VadamaradchiVadamaradchi South-WestSouth-West (Karaveddy)(Karaveddy) Island North (Kayts) JaffnaJaffna VadamaradchiVadamaradchi EastEast Divisions.WOR Affected Jaffna DelftDelft DelftDelftIsland South (Velanai) KillinochchiKillinochchi KILINOCHCHIKILINOCHCHI KillinochchiKillinochchi PuthukudiyiruppuPuthukudiyiruppu MULLAITIVUMULLAITIVU MaritimepattuMaritimepattu 9°N MannarMannar VAVUNIYAVAVUNIYA MANNARMANNAR KuchchaveliKuchchaveli VavuniyaVavuniya TrincomaleeTrincomalee TownTown andand GravetsGravets MorawewaMorawewa TrincomaleeTrincomalee KinniyaKinniya ANURADHAPURAANURADHAPURA ThambalagamuwaThambalagamuwa MutturMuttur TRINCOMALEETRINCOMALEE SeruvilaSeruvila Verugal/Verugal/ EchchilampattaiEchchilampattai KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu NorthNorth KalpitiyaKalpitiya PUTTALAMPUTTALAM POLONNARUWAPOLONNARUWA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Oddamavadi)(Oddamavadi) 8°N KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Valachchenai)(Valachchenai) MundelMundel KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown KURUNEGALAKURUNEGALA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown ManmunaiManmunai NorthNorth ArachchikattuwaArachchikattuwa BatticaloaBatticaloa EravurEravur PattuPattu BatticaloaBatticaloaKattankudyKattankudy ManmunaiManmunai -

Vea Un Ejemplo

3 To search aircraft in the registration index, go to page 178 Operator Page Operator Page Operator Page Operator Page 10 Tanker Air Carrier 8 Air Georgian 20 Amapola Flyg 32 Belavia 45 21 Air 8 Air Ghana 20 Amaszonas 32 Bering Air 45 2Excel Aviation 8 Air Greenland 20 Amaszonas Uruguay 32 Berjaya Air 45 748 Air Services 8 Air Guilin 20 AMC 32 Berkut Air 45 9 Air 8 Air Hamburg 21 Amelia 33 Berry Aviation 45 Abu Dhabi Aviation 8 Air Hong Kong 21 American Airlines 33 Bestfly 45 ABX Air 8 Air Horizont 21 American Jet 35 BH Air - Balkan Holidays 46 ACE Belgium Freighters 8 Air Iceland Connect 21 Ameriflight 35 Bhutan Airlines 46 Acropolis Aviation 8 Air India 21 Amerijet International 35 Bid Air Cargo 46 ACT Airlines 8 Air India Express 21 AMS Airlines 35 Biman Bangladesh 46 ADI Aerodynamics 9 Air India Regional 22 ANA Wings 35 Binter Canarias 46 Aegean Airlines 9 Air Inuit 22 AnadoluJet 36 Blue Air 46 Aer Lingus 9 Air KBZ 22 Anda Air 36 Blue Bird Airways 46 AerCaribe 9 Air Kenya 22 Andes Lineas Aereas 36 Blue Bird Aviation 46 Aereo Calafia 9 Air Kiribati 22 Angkasa Pura Logistics 36 Blue Dart Aviation 46 Aero Caribbean 9 Air Leap 22 Animawings 36 Blue Islands 47 Aero Flite 9 Air Libya 22 Apex Air 36 Blue Panorama Airlines 47 Aero K 9 Air Macau 22 Arab Wings 36 Blue Ridge Aero Services 47 Aero Mongolia 10 Air Madagascar 22 ARAMCO 36 Bluebird Nordic 47 Aero Transporte 10 Air Malta 23 Ariana Afghan Airlines 36 Boliviana de Aviacion 47 AeroContractors 10 Air Mandalay 23 Arik Air 36 BRA Braathens Regional 47 Aeroflot 10 Air Marshall Islands 23