Understandings of Science and Faith in Yaoundé, Abidjan, and Kinshasa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Kié: Future Africa Foundation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons The ERFIP collection ( an initiative of the Edmond de Rothschild Foundation) Graduate School of Education 2020 Charles Kié: Future Africa Foundation Sharon Ravitch Gul Rukh Rahman Reima Shakeir Shakeir Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/erfip Ravitch, Sharon; Rahman, Gul Rukh; and Shakeir, Reima Shakeir, "Charles Kié: Future Africa Foundation" (2020). The ERFIP collection ( an initiative of the Edmond de Rothschild Foundation). 2. https://repository.upenn.edu/erfip/2 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/erfip/2 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Charles Kié: Future Africa Foundation Abstract The founders of Future Africa created the Foundation (FAF) in 2013 to give underprivileged children the chance to access good quality education in a healthy environment. One of its stated aims is to educate the masses about environmental issues including plastic waste, recycling and preservation with a view to building healthy environments and creating sustainable businesses for improved livelihoods. The Foundation differentiates itself by taking a 360° view of multiple intertwined problems: lack of access to quality education, women’s empowerment, environmental protection practices, sustainable businesses – all through improved waste management solutions. The Foundation aims to dive deep and address the root causes of these burgeoning issues. It takes a circular economy-like approach to maximize resource utilization -

South African Airways Timetable

102 103 SAA / OUR FLIGHTS OUR FLIGHTS / SAA SOUTH AFRICAN AIRWAYS TIMETABLE As Africa’s most-awarded airline, SAA operates from Johannesburg to 32 destinations in 22 countries across the globe Our extensive domestic schedule has a total Nairobi, Ndola, Victoria Falls and Windhoek. SAA’s international of 284 flights per week between Johannesburg, network creates links to all major continents from our country Cape Town, Durban, East London and Port through eight direct routes and codeshare flights, with daily Elizabeth. We have also extended our codeshare flights from Johannesburg to Frankfurt, Hong Kong, London REGIONAL agreement with Mango, our low-cost operator, (Heathrow), Munich, New York (JFK), Perth, São Paulo and CARRIER FLIGHT FREQUENCY FROM DEPARTS TO ARRIVES to include coastal cities in South Africa (between Washington (Dulles). We have codeshare agreements with SA 144 1234567 Johannesburg 14:20 Maputo 15:20 Johannesburg and Cape Town, Durban, Port Elizabeth and 29 other airlines. SAA is a member of Star Alliance, which offers SA 145 1234567 Maputo 16:05 Johannesburg 17:10 George), as well as Johannesburg-Bloemfontein, Cape Town- more than 18 500 daily flights to 1 321 airports in 193 countries. SA 146 1234567 Johannesburg 20:15 Maputo 21:15 Bloemfontein and Cape Town-Port Elizabeth. Regionally, SAA SAA has won the “Best Airline in Africa” award in the regional SA 147 1234567 Maputo 07:30 Johannesburg 08:35 offers 19 destinations across the African continent, namely Abidjan, category for 15 consecutive years. Mango and SAA hold the SA 160 1.34567 Johannesburg 09:30 Entebbe 14:30 Accra, Blantyre, Dakar, Dar es Salaam, Entebbe, Harare, Kinshasa, number 1 and 2 spots as South Africa’s most on-time airlines. -

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions”

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions” Abstract Abidjan is the political capital of Ivory Coast. This five million people city is one of the economic motors of Western Africa, in a country whose democratic strength makes it an example to follow in sub-Saharan Africa. However, when disasters such as floods strike, their most vulnerable areas are observed and consequences such as displacements, economic desperation, and even public health issues occur. In this research, I looked at the problem of flooding in Abidjan by focusing on their institutional response. I analyzed its institutional resilience at three different levels: local, national, and international. A total of 20 questionnaires were completed by 20 different participants. Due to the places where the respondents lived or worked when the floods occurred, I focused on two out of the 10 communes of Abidjan after looking at the city as a whole: Macory (Southern Abidjan) and Cocody (Northern Abidjan). The goal was to talk to the Abidjan population to gather their thoughts from personal experiences and to look at the data published by these institutions. To analyze the information, I used methodology combining a qualitative analysis from the questionnaires and from secondary sources with a quantitative approach used to build a word-map with the platform Voyant, and a series of Arc GIS maps. The findings showed that the international organizations responded the most effectively to help citizens and that there is a general discontent with the current local administration. The conclusions also pointed out that government corruption and lack of infrastructural preparedness are two major problems affecting the overall resilience of Abidjan and Ivory Coast to face this shock. -

COP 2 Decisions

UNEP/(DEC)/EAF/CP.2/7 Page 11 Annex I DECISIONS OF THE SECOND MEETING OF THE CONTRACTING PARTIES TO THE CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION, MANAGEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENT OF THE EASTERN AFRICAN REGION The Contracting Parties, Recalling decision CP.1/4 of the Nairobi Convention, in accordance with Article 17, paragraph 1 (d) of the Convention, decided to consider the feasibility and modalities of updating the text of the Convention and its related protocols and to formulate and adopt guidelines for the management of its Protocol concerning Protected Areas and Wild Fauna and Flora in the Eastern African Region, Taking note, with appreciation of the progress report of the Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme on the work done by the Ad Hoc Technical and Legal Working Group on the review to update the Nairobi Convention and the Protocol Concerning Protected Areas and Wild Fauna and Flora in the Eastern African Region, Further taking note that over fourteen years have elapsed since the adoption of the Nairobi Convention and that the African Governments recently embarked on a comprehensive assessment of the setbacks of the regional seas programme in Africa, Taking note of decision 19/14 A of 7 February 1997 of the Governing Council of the United Nations Environment Programme, by which the Council decided, inter alia, to strengthen the regional seas programme and coastal zone management approach, as called for in the Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment -

The Urban Heat Island Effect and Sustainability Science: Causes, Impacts, and Solutions 275

Chapter 14 The Urban Heat Island Effect and Sustainability Science: Causes, Impacts, and Solutions Darren Ruddell, Anthony Brazel, Winston Chow, Ariane Middel Introduction As Chapter 3 described, urbanization began approximately 10,000 years ago Urbanization The process when people first started organizing into small permanent settlements. whereby native landscapes While people initially used local and organic materials to meet residential are converted to urban land and community needs, advances in science, technology, and transportation uses, such as commercial systems support urban centers that rely on distant resources to produce and residential development. engineered surfaces and synthetic materi- als. This process of urbanization, Urbanization is also defined which manifests in both population and spatial extent, has increased over as rural migration to urban the course of human history. For instance, according to the 2014 US Census, centers. the global population has rapidly increased from 1 billion people in 1804 to 7.1 billion in 2014. During the same period, the global population living in urban centers grew from 3% to over 52% (US Census, 2014). In 1950, there were 86 cities in the world with a population of more than 1 million. This number has grown to 512 cities in 2016 with a projected 662 cities by 2030 (UN, 2016). Megacities (urban agglomerations with populations greater than 10 million) have also become commonplace throughout the world. In Megacities Urban 2016, the UN determined that there are 31 megacities globally and agglomerations, including estimate that this number will increase to 41 by 2030. The highest rates of all of the contiguous urban urbanization and most megacities are in the developing world, area, or built-up area. -

Stan Douglas Born 1960 in Vancouver

This document was updated February 25, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Stan Douglas Born 1960 in Vancouver. Lives and works in Vancouver. EDUCATION 1982 Emily Carr College of Art, Vancouver SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Stan Douglas: Doppelgänger, David Zwirner, New York, concurrently on view at Victoria Miro, London 2019 Luanda-Kinshasa by Stan Douglas, Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, Winnipeg, Canada Stan Douglas: Hors-champs, Western Front, Vancouver Stan Douglas: SPLICING BLOCK, Julia Stoschek Collection (JSC), Berlin [collection display] [catalogue] 2018 Stan Douglas: DCTs and Scenes from the Blackout, David Zwirner, New York Stan Douglas: Le Détroit, Musée d'Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean (MUDAM), Luxembourg 2017 Stan Douglas, Victoria Miro, London Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa, Les Champs Libres, Rennes, France 2016 Stan Douglas: Photographs, David Zwirner, New York Stan Douglas: The Secret Agent, David Zwirner, New York Stan Douglas: The Secret Agent, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg [catalogue] Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa, Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) Stan Douglas: The Secret Agent, Victoria Miro, London Stan Douglas, Hasselblad Center, Gothenburg, Sweden [organized on occasion of the artist receiving the 2016 Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography] [catalogue] 2015 Stan Douglas: Interregnum, Museu Coleção Berardo, Lisbon [catalogue] Stan Douglas: Interregnum, Wiels Centre d’Art Contemporain, Brussels [catalogue] 2014 Stan Douglas: -

Kitona Operations: Rwanda's Gamble to Capture Kinshasa and The

Courtesy of Author Courtesy of Author of Courtesy Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers during 1998 Congo war and insurgency Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers guard refugees streaming toward collection point near Rwerere during Rwanda insurgency, 1998 The Kitona Operation RWANDA’S GAMBLE TO CAPTURE KINSHASA AND THE MIsrEADING OF An “ALLY” By JAMES STEJSKAL One who is not acquainted with the designs of his neighbors should not enter into alliances with them. —SUN TZU James Stejskal is a Consultant on International Political and Security Affairs and a Military Historian. He was present at the U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda, from 1997 to 2000, and witnessed the events of the Second Congo War. He is a retired Foreign Service Officer (Political Officer) and retired from the U.S. Army as a Special Forces Warrant Officer in 1996. He is currently working as a Consulting Historian for the Namib Battlefield Heritage Project. ndupress.ndu.edu issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 / JFQ 99 RECALL | The Kitona Operation n early August 1998, a white Boeing remain hurdles that must be confronted by Uganda, DRC in 1998 remained a safe haven 727 commercial airliner touched down U.S. planners and decisionmakers when for rebels who represented a threat to their unannounced and without warning considering military operations in today’s respective nations. Angola had shared this at the Kitona military airbase in Africa. Rwanda’s foray into DRC in 1998 also concern in 1996, and its dominant security I illustrates the consequences of a failure to imperative remained an ongoing civil war the southwestern Bas Congo region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

April 2020 (FY 2020)

Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post April 2020 (FY 2020) Post Visa Class Issuances Abidjan DV1 1 Abidjan FX1 2 Abidjan FX3 1 Abidjan IR2 1 Abidjan IR5 2 Abu Dhabi E31 1 Abu Dhabi E34 1 Abu Dhabi E35 1 Abu Dhabi F41 1 Abu Dhabi F42 1 Abu Dhabi F43 1 Abu Dhabi IR1 1 Abu Dhabi IR2 1 Addis Ababa CR1 2 Addis Ababa FX1 1 Addis Ababa FX3 3 Addis Ababa IR1 3 Addis Ababa IR2 3 AIT Taipei CR1 9 AIT Taipei E21 2 AIT Taipei E22 1 AIT Taipei E23 1 AIT Taipei F11 1 AIT Taipei F31 1 AIT Taipei F32 1 AIT Taipei F33 2 AIT Taipei F41 1 AIT Taipei F42 1 AIT Taipei F43 2 AIT Taipei FX2 1 AIT Taipei IR1 1 AIT Taipei IR5 6 AIT Taipei SB1 3 Amman CR1 1 Amsterdam CR1 3 Amsterdam IR1 2 Ankara CR1 3 Ankara DV1 1 Ankara DV2 1 Ankara DV3 1 Ankara E21 1 Page 1 of 12 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post April 2020 (FY 2020) Post Visa Class Issuances Ankara F41 1 Ankara F42 1 Ankara F43 2 Ankara FX2 3 Ankara I51 1 Ankara I52 1 Ankara I53 1 Ankara IR1 4 Ankara IR5 3 Ankara SE3 1 Ashgabat FX1 1 Ashgabat FX3 1 Baghdad DV1 1 Baghdad DV2 1 Baghdad DV3 3 Baghdad F32 1 Baghdad IR1 1 Baghdad SQ1 2 Baghdad SQ3 2 Belgrade IR1 1 Bern CR1 1 Bern IR1 2 Bogota CR1 2 Bogota CR2 2 Bogota E11 1 Bogota E14 1 Bogota E15 3 Bogota F11 3 Bogota F31 2 Bogota F32 2 Bogota F33 3 Bogota F41 3 Bogota F42 2 Bogota F43 3 Bogota FX1 4 Bogota FX2 1 Bogota FX3 2 Bogota IH3 9 Bogota IR1 4 Bogota IR5 5 Bratislava IR1 2 Page 2 of 12 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post April 2020 (FY 2020) Post Visa Class Issuances Bratislava IR2 1 Brussels CR1 1 Bucharest IR1 1 Budapest CR1 1 Budapest IH3 5 Buenos Aires F11 1 -

Unidad De Funcionarios Internacionales Vacantes

UNIDAD DE FUNCIONARIOS INTERNACIONALES VACANTES EN OOII 16/12/20 Se muestran las vacantes que han publicado las Organizaciones Internacionales durante la última semana, detallando el organismo, la fecha de caducidad, el enlace a la vacante, la categoría y el lugar de destino. Debido a las restricciones de personal a consecuencia del Covid-19, no podemos confeccionar el boletín con el anterior formato, en cuanto nos sea posible volveremos a hacerlo. Se adjunta cuadro orientativo de las categorías y niveles Sistema ONU FIELD Organizaciones UNOPS CERN Años experiencia ONU y SUPPORT Coordinadas OTAN, OSCE OCDE y otras ASG ADG D2 A7 >15 D1 FS-7 A6 15 + P5 FS-6 A5 IICA-4 Sin 10 + P4 FS-5 A4 IICA-3 categoría 7 + P3 FS-4 A3 IICA-2 5 + P2 FS-3 A2 IICA-1 2 + P1 A1 Sin experiencia + En aquellas Organizaciones Internacionales que no disponen de categorías o niveles (o que disponiendo de ellas no se asimilen a los sistemas de las OO.II. como Naciones Unidas, OTAN, etc.) se ha optado por adjudicar a sus vacantes una categoría ya existente en función de la experiencia requerida en el puesto ofertado. http://ufi.ooii.maec.es Email: [email protected] VACANTES DEL 10 AL 16 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2.020 AEE 12-01 G2G Mission Planning Engineer, A2/A4, https://career2.successfactors.eu/career?career%5fns=job%5flisting&company=esa&navBarL evel=JOB%5fSEARCH&rcm%5fsite%5flocale=en%5fGB&career_job_req_id=10123&selected_la ng=en_GB&jobAlertController_jobAlertId=&jobAlertController_jobAlertName=&_s.crb=bn2xY %2ffdbiYQv5eRWN5qadym7oPdyVxOoBZI0yIanzk%3d NOORDWIJK 21-01 Finance -

ETHIOPIAN the LARGEST AIRLINE in AFRICA FACT SHEET Overview

ETHIOPIAN THE LARGEST AIRLINE IN AFRICA FACT SHEET Overview Ethiopian Airlines (Ethiopian) is the leading and most profitable airline in Africa. In 2014 IATA ranked Ethiopian as the largest airline in Africa in revenue and profit. Over the past seven decades, Ethiopian has been a pioneer of African aviation as an aircraft technology leader. Ethiopian provided the first jet service in the continent in 1962, the first African B787 Dreamliner in 2012 and is leading the way again by providing the first African A350 XWB. Ethiopian joined Star Alliance, the world’s largest Airline network, in December 2011. Ethiopian is currently implementing a 15-year strategic plan called Vision 2025 that will see it become the leading airline group in Africa with seven strategic business units. Ethiopian is a multi-award winning airline, including SKYTRAX and Passenger Choice Awards in 2015, and has been registering an average growth of 25% per annum for the past ten years. Ethiopian Background Information Founded E December 21, 1945 Starting date of operation E April 08, 1946 Ownership E Government of Ethiopia (100%) Head Office E Bole International Airport, P.O. Box 1755 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Fax: (+ 251)11661 1474 Reservations E Tel: (+251) 11 665 6666 Website E http://www.ethiopianairlines.com Chief Executive Officer E Mr. Tewolde GebreMariam Fleet Summary Aircraft Inventory: 82 Flett on order: 51 Average age of aircraft: 5 years Passenger aircraft Airbus - A350-900 2 Airbus - A350-900 12 Boeing 787-800 16 Boeing 787-9 4 Boeing 777-300ER 4 Boeing 787-800 -

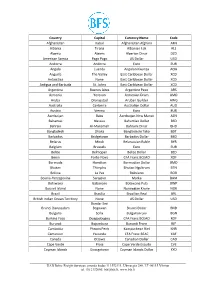

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Supplementary Material Barriers and Facilitators to Pre-Exposure

Sexual Health, 2021, 18, 130–39 © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Supplementary Material Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis among A frican migr ants in high income countries: a systematic review Chido MwatururaA,B,H, Michael TraegerC,D, Christopher LemohE, Mark StooveC,D, Brian PriceA, Alison CoelhoF, Masha MikolaF, Kathleen E. RyanA,D and Edwina WrightA,D,G ADepartment of Infectious Diseases, The Alfred and Central Clinical School, Monash Un iversity, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. BMelbourne Medical School, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. CSchool of Public Health and Preventative Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. DBurnet Institute, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. EMonash Infectious Diseases, Monash Health, Melbourne, Vi, Auc. stralia. FCentre for Culture, Ethnicity & Health, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. GPeter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. HCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] File S1 Appendix 1: Syntax Usedr Dat fo abase Searches Appendix 2: Table of Excluded Studies ( n=58) and Reasons for Exclusion Appendix 3: Critical Appraisal of Quantitative Studies Using the ‘ Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies’ (39) Appendix 4: Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies U sing a modified ‘CASP Qualitative C hecklist’ (37) Appendix 5: List of Abbreviations Sexual Health © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Appendix 1: Syntax Used for Database