The Study of Ancient Territories Chersonesos & South Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Huygens on Translation

HUYGENS ON TRANSLATION Theo Hermans 1 The tercentenary of the death of Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687) presents a convenient occasion to trace the views held by this versatile and multilingual writer on the subject of translation. A first inventory of Huygens' pronouncements on the matter is all that will be attempted here. The choice of Huygens is not dictated by commemorative considerations alone. Both the contemporary appreciation of his work as a translator – notably of John Donne – and the fact that, as in Vondel's case, some of Huygens' comments on translation are echoed and occasionally challenged by other translators, indicate that his approach to the subject is sufficiently central to be treated as a point of reference. 2 Huygens' extraordinary gifts as a linguist are well known, as is the fact that he began to write poems in Latin at the age of 11 and in French at 16, two years before he tried his hand at Dutch verse. It has been calculated that of the more than 75,000 lines of verse in Worp's edition of Huygens' Collected Poems, 64.3% are in Dutch, 26.4% in Latin and 8.7% in French, with Italian, Greek, German and Spanish making up the remaining 0.6% (Van Seggelen 1987:72). His skill as a multilingual versifier can be breathtaking: in one of his more playful polyglot moods he presents his friend Jacob van der Burgh with an "Olla podrida" poem, dated 11 March 1625, with lines in Dutch, Latin, Greek, Italian, French, Spanish, German and English (Ged. II: 111-13). -

SDN Changes 2014

OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES TO THE Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List SINCE JANUARY 1, 2014 This publication of Treasury's Office of Foreign AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah (a.k.a. SAHAB, Qari; IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN Assets Control ("OFAC") is designed as a a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH; a.k.a. reference tool providing actual notice of actions by 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. OFAC with respect to Specially Designated Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, "SUPPORTERS OF ISLAMIC LAW"), Tunisia Nationals and other entities whose property is Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) [FTO] [SDGT]. blocked, to assist the public in complying with the [SDGT]. AL-RAYA ESTABLISHMENT FOR MEDIA various sanctions programs administered by SAHAB, Qari (a.k.a. AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah; PRODUCTION (a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA; OFAC. The latest changes may appear here prior a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'A BRIGADE; a.k.a. to their publication in the Federal Register, and it 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'A IN BENGHAZI; a.k.a. is intended that users rely on changes indicated in Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN LIBYA; a.k.a. ANSAR this document that post-date the most recent Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) AL-SHARIAH; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIAH Federal Register publication with respect to a [SDGT]. -

Amazons, Thracians, and Scythians , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 24:2 (1983:Summer) P.105

SHAPIRO, H. A., Amazons, Thracians, and Scythians , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 24:2 (1983:Summer) p.105 Amazons, Thracians, and Scythians H A. Shapiro HE AMAZONS offer a remarkable example of the lacunose and T fragmented state of ancient evidence for many Greek myths. For while we hear virtually nothing about them in extant litera ture before the mid-fifth century, they are depicted in art starting in the late eighth! and are extremely popular, especially in Attica, from the first half of the sixth. Thus all we know about the Greeks' con ception of the Amazons in the archaic period comes from visual rep resentations, not from written sources, and it would be hazardous to assume that various 'facts' and details supplied by later writers were familiar to the sixth-century Greek. The problem of locating the Amazons is a good case in point. Most scholars assume that Herakles' battle with the Amazons, so popular on Attic vases, took place at the Amazon city Themiskyra in Asia Minor, on the river Thermodon near the Black Sea, where most ancient writers place it.2 But the earliest of these is Apollodoros (2.5.9), and, as I shall argue, alternate traditions locating the Ama zons elsewhere may have been known to the archaic vase-painter and viewer. An encounter with Amazons figures among the exploits of three important Greek heroes, and each story entered the Attic vase painters' repertoire at a different time in the course of the sixth century. First came Herakles' battle to obtain the girdle of Hippolyte (although the prize itself is never shown), his ninth labor. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Writing in the Street: The Development of Urban Poetics in Roman Satire Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7x66m4vs Author Gillies, Grace Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Writing in the Street: The Development of Urban Poetics in Roman Satire A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Grace Gillies 2018 © Copyright by Grace Gillies 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Writing in the Street: The Development of Urban Poetics in Roman Satire by Grace Gillies Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Amy Ellen Richlin, Chair My dissertation examines Roman imperial satire for its relationship with non-elite street culture in the Roman city. I begin with a lexicon of sites and terms related to Roman concepts of disgust in the city, as they appear in the satiric sources I am working with. Then, in my next four chapters, I work chronologically through the extant satires to show how each author reflects or even appropriates practices from Roman street culture. Satirists both condemn parts of the city as disgusting—the parts and people in them who ignore social and cultural boundaries—and appropriate those practices as emblematic of what satire does. The theoretical framework for this project concerns concepts of disgust in the Roman world, and draws primarily on Mary Douglas (1966) and Julia Kristeva (1982). The significance of this work is twofold: (1) it argues that satire is, far from a self-contained elite practice, a genre that drew heavily on non-elite urban ii culture; (2) that it adds to a fragmentary history of Roman street culture. -

Ovid's Metamorphoses in Twentieth-Century Italian Literature

alberto comparini (Ed.) Ovid’s comparini comparini Metamorphoses in Twentieth-Century comparini (Ed.) Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Ed.) in Twentieth-Century Italian Literature Italian Literature his book aims to show the metamorphic nature of Ovid’s reception in twentieth-century Italian literature. It is a study of the aesthetic effects of Ovid’s poetics Italian Literature Twentieth-Century in Metamorphoses Ovid’s within both the novel and poetry tradition in Italy. By using a historical and philological methodology, the authors of each essay have shown the hermeneutic power of Ovid, read as a constant intertextual presence. From Giovanni Pascoli to Eugenio Montale, from Italo Calvino to Antonio Tabucchi, in this book Ovid’s recep- tion is finally shown to be as important as Virgil’s and offers new important tools in order to understand the role of Latin literature in the twentieth century. Universitätsverlag winter isbn 978-3-8253-6788-6 Heidelberg bibliothek der klassischen altertumswissenschaften Herausgegeben von jürgen paul schwindt Neue Folge · 2. Reihe · Band 157 alberto comparini (Ed.) Ovid’s Metamorphoses in Twentieth-Century Italian Literature Universitätsverlag winter Heidelberg Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. cover illustration © Barbara Heinisch: Prozessmalerei im Düsseldorfer Atelier mit der Tänzerin Sayonara Pereira, 1992, Privatsammlung, Gelsenkirchen, Nutzung und Bildbearbeitung gemäß Creative Commons-Lizenz cc by-sa 3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36243658 isbn 978-3-8253-6788-6 Dieses Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. -

APPLICATION of the CHARTER in UKRAINE 2Nd Monitoring Cycle A

Strasbourg, 15 January 2014 ECRML (2014) 3 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES APPLICATION OF THE CHARTER IN UKRAINE 2nd monitoring cycle A. Report of the Committee of Experts on the Charter B. Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the application of the Charter by Ukraine The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages provides for a control mechanism to evaluate how the Charter is applied in a State Party with a view to, where necessary, making recommendations for improving its language legislation, policy and practices. The central element of this procedure is the Committee of Experts, set up under Article 17 of the Charter. Its principal purpose is to report to the Committee of Ministers on its evaluation of compliance by a Party with its undertakings, to examine the real situation of regional or minority languages in the State and, where appropriate, to encourage the Party to gradually reach a higher level of commitment. To facilitate this task, the Committee of Ministers adopted, in accordance with Article 15, paragraph1, an outline for periodical reports that a Party is required to submit to the Secretary General. The report should be made public by the State. This outline requires the State to give an account of the concrete application of the Charter, the general policy for the languages protected under Part II and, in more precise terms, all measures that have been taken in application of the provisions chosen for each language protected under Part III of the Charter. The Committee of Experts’ first task is therefore to examine the information contained in the periodical report for all the relevant regional or minority languages on the territory of the State concerned. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

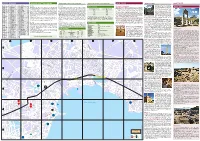

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

Pottery from Roman Malta

Cover Much of what is known about Malta’s ancient material culture has come to light as a result of antiquarian research or early archaeological work – a time where little attention Anastasi MALTA ARCHAEOLOGICAL REVIEW SUPPLEMENT 1 was paid to stratigraphic context. This situation has in part contributed to the problem of reliably sourcing and dating Maltese Roman-period pottery, particularly locally produced forms common on nearly all ancient Maltese sites. Pottery from Roman Malta presents a comprehensive study of Maltese pottery forms from key stratified deposits spanning the first century BC to mid-fourth century AD. Ceramic material from three Maltese sites was analysed and quantified in a bid to understand Maltese pottery production during the Roman period, and trace the type and volume of ceramic-borne goods that were circulating the central Mediterranean during the period. A short review of the islands’ recent literature on Roman pottery is discussed, followed by a detailed Pottery from Roman Malta contextual summary of the archaeological contexts presented in this study. The work is supplemented by a detailed illustrated catalogue of all the forms identified within the assemblages, presenting the wide range of locally produced and imported pottery types typical of the Maltese Roman period. Maxine Anastasi is a Lecturer at the Department of Classics and Archaeology, University of Malta. She was awarded a DPhil in Archaeology from the University of Oxford for her dissertation on small-island economies in the Central Mediterranean. Her research primarily focuses on Roman pottery in the central Mediterranean, with a particular Malta from Roman Pottery emphasis on Maltese assemblages. -

Baltic States And

UNCLASSIFIED Asymmetric Operations Working Group Ambiguous Threats and External Influences in the Baltic States and Poland Phase 1: Understanding the Threat October 2014 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Cover image credits (clockwise): Pro-Russian Militants Seize More Public Buildings in Eastern Ukraine (Donetsk). By Voice of America website (VOA) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:VOAPro- Russian_Militants_Seize_More_Public_Buildings_in_Eastern_Ukraine.jpg. Ceremony Signing the Laws on Admitting Crimea and Sevastopol to the Russian Federation. The website of the President of the Russian Federation (www.kremlin.ru) [CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ceremony_signing_ the_laws_on_admitting_Crimea_and_Sevastopol_to_the_Russian_Federation_1.jpg. Sloviansk—Self-Defense Forces Climb into Armored Personnel Carrier. By Graham William Phillips [CCBY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia. org/wiki/File:BMDs_of_Sloviansk_self-defense.jpg. Dynamivska str Barricades on Fire, Euromaidan Protests. By Mstyslav Chernov (http://www.unframe.com/ mstyslav- chernov/) (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dynamivska_str_barricades_on_fire._ Euromaidan_Protests._Events_of_Jan_19,_2014-9.jpg. Antiwar Protests in Russia. By Nessa Gnatoush [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Euromaidan_Kyiv_1-12-13_by_ Gnatoush_005.jpg. Military Base at Perevalne during the 2014 Crimean Crisis. By Anton Holoborodko (http://www. ex.ua/76677715) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2014-03-09_-_Perevalne_military_base_-_0180.JPG. -

Attic Pottery of the Later Fifth Century from the Athenian Agora

ATTIC POTTERY OF THE LATER FIFTH CENTURY FROM THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATES 73-103) THE 1937 campaign of the American excavations in the Athenian Agora included work on the Kolonos Agoraios. One of the most interesting results was the discovery and clearing of a well 1 whose contents proved to be of considerable value for the study of Attic pottery. For this reason it has seemed desirable to present the material as a whole.2 The well is situated on the southern slopes of the Kolonos. The diameter of the shaft at the mouth is 1.14 metres; it was cleared to the bottom, 17.80 metres below the surface. The modern water-level is 11 metres down. I quote the description from the excavator's notebook: The well-shaft, unusually wide and rather well cut widens towards the bottom to a diameter of ca. 1.50 m. There were great quantities of pot- tery, mostly coarse; this pottery seems to be all of the same period . and joins In addition to the normal abbreviations for periodicals the following are used: A.B.C. A n tiquites du Bosphore Cimmerien. Anz. ArchaiologischerAnzeiger. Deubner Deubner, Attische Feste. FR. Furtwangler-Reichhold, Griechische Vasenmxlerei. Kekule Kekule, Die Reliefs an der Balustrade der Athena Nike. Kraiker Kraiker,Die rotfigurigenattischen Vasen (Collectionof the ArchaeologicalIn- stitute of Heidelberg). Langlotz Langlotz, Griechische Vasen in Wiirzburg. ML. Monumenti Antichi Pu'bblicatiper Cura della Reale Accadenia dei Lincei. Rendiconti Rendiconti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei. Richter and Hall Richter and Hall, Red-Figured Athenian Vases in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. -

Crimea______9 3.1

CONTENTS Page Page 1. Introduction _____________________________________ 4 6. Transport complex ______________________________ 35 1.1. Brief description of the region ______________________ 4 1.2. Geographical location ____________________________ 5 7. Communications ________________________________ 38 1.3. Historical background ____________________________ 6 1.4. Natural resource potential _________________________ 7 8. Industry _______________________________________ 41 2. Strategic priorities of development __________________ 8 9. Energy sector ___________________________________ 44 3. Economic review 10. Construction sector _____________________________ 46 of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea ________________ 9 3.1. The main indicators of socio-economic development ____ 9 11. Education and science ___________________________ 48 3.2. Budget _______________________________________ 18 3.3. International cooperation _________________________ 20 12. Culture and cultural heritage protection ___________ 50 3.4. Investment activity _____________________________ 21 3.5. Monetary market _______________________________ 22 13. Public health care ______________________________ 52 3.6. Innovation development __________________________ 23 14. Regions of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea _____ 54 4. Health-resort and tourism complex_________________ 24 5. Agro-industrial complex __________________________ 29 5.1. Agriculture ____________________________________ 29 5.2. Food industry __________________________________ 31 5.3. Land resources _________________________________