Peter Viereck's View of Metternich's Conservative Internationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980 Robert L. Richardson, Jr. A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by, Michael H. Hunt, Chair Richard Kohn Timothy McKeown Nancy Mitchell Roger Lotchin Abstract Robert L. Richardson, Jr. Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1985 (Under the direction of Michael H. Hunt) This dissertation examines the origins and evolution of neoconservatism as a philosophical and political movement in America from 1945 to 1980. I maintain that as the exigencies and anxieties of the Cold War fostered new intellectual and professional connections between academia, government and business, three disparate intellectual currents were brought into contact: the German philosophical tradition of anti-modernism, the strategic-analytical tradition associated with the RAND Corporation, and the early Cold War anti-Communist tradition identified with figures such as Reinhold Niebuhr. Driven by similar aims and concerns, these three intellectual currents eventually coalesced into neoconservatism. As a political movement, neoconservatism sought, from the 1950s on, to re-orient American policy away from containment and coexistence and toward confrontation and rollback through activism in academia, bureaucratic and electoral politics. Although the neoconservatives were only partially successful in promoting their transformative project, their accomplishments are historically significant. More specifically, they managed to interject their views and ideas into American political and strategic thought, discredit détente and arms control, and shift U.S. foreign policy toward a more confrontational stance vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. -

Imagination Movers: the Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism

Imagination Movers: The Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism Seth James Bartee Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Francois Debrix, Chair Matthew Gabriele Matthew Dallek James Garrison Timothy Luke February 19, 2014 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: conservatism, imagination, historicism, intellectual history counter-narrative, populism, traditionalism, paleo-conservatism Imagination Movers: The Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism Seth James Bartee ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to explore what exactly bound post-Second World War American conservatives together. Since modern conservatism’s recent birth in the United States in the last half century or more, many historians have claimed that both anti-communism and capitalism kept conservatives working in cooperation. My contention was that the intellectual founder of postwar conservatism, Russell Kirk, made imagination, and not anti-communism or capitalism, the thrust behind that movement in his seminal work The Conservative Mind. In The Conservative Mind, published in 1953, Russell Kirk created a conservative genealogy that began with English parliamentarian Edmund Burke. Using Burke and his dislike for the modern revolutionary spirit, Kirk uncovered a supposedly conservative seed that began in late eighteenth-century England, and traced it through various interlocutors into the United States that culminated in the writings of American expatriate poet T.S. Eliot. What Kirk really did was to create a counter-narrative to the American liberal tradition that usually began with the French Revolution and revolutionary figures such as English-American revolutionary Thomas Paine. -

A Third View of the New Deal Peter Viereck

New Mexico Quarterly Volume 26 | Issue 1 Article 7 1956 A Third View of the New Deal Peter Viereck Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq Recommended Citation Viereck, Peter. "A Third View of the New Deal." New Mexico Quarterly 26, 1 (1956). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq/vol26/ iss1/7 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Mexico Press at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Quarterly by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Viereck: A Third View of the New Deal Peter Viereck A THIRD VIEW OF THE NEW DEAL "Men fight and lose the battle, and the thing they fought for comes about in .pite of their defeat; and when it comes, turns out to be not what they meant; and other men have to fight for what they meant under another name,"-WlLLIAM MOlUUS :- "Thestrange alchemy of time h3.! somehow converted the Democrats into the truly conservative party of this country-the party dedicated to conserving all that is belt, and building solidly and sarely on these foundaqons:'-ADLAl STEVENSON, 1952 I EW DEAL LIBERAL: "The New Deal was not com munist-infiltrated, as the hysterical witch-hunters N. charged. Instead, it represented a native radicalism that wisely hindered Wall Street, educated the masses to become less conservative than before, and discarded outdated institutions." Republican: "The New Deal was communist-infiltrated, just as our patriotic businessmen charged at the time. -

Rescuing Burke

Missouri Law Review Volume 72 Issue 2 Spring 2007 Article 1 Spring 2007 Rescuing Burke Carl T. Bogus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Carl T. Bogus, Rescuing Burke, 72 MO. L. REV. (2007) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol72/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bogus: Bogus: Rescuing Burke MISSOURI LAW REVIEW VOLUME 72 SPRING 2007 NUMBER 2 Rescuing Burke Carl T. Bogus* I. INTRODUCTION Edmund Burke needs to be rescued. His legacy is held hostage by the modem conservative movement, which proclaims Burke to be its intellectual progenitor. Conservatives consider Burke the fountainhead of their political philosophy - the great thinker and eloquent eighteenth-century British statesman who provides conservatism with a distinguished heritage and a coherent body of thought. Burke has achieved iconic status; Reaganites wore his silhouette on their neckties.' Legal scholars applaud court decisions and jurisprudential philosophies as Burkean, or denounce them as not being genu- inely Burkean. But Burke's memory has been wrongfully appropriated. Ed- mund Burke was a liberal - at least by today's standards - and it is time to restore him to his proper home. This Article has three objectives. The first is to demonstrate Burke's lib- eralism. -

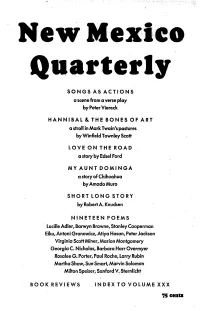

SONGS AS ACTIONS a Scene from a Verse Play by Peter Viereck HAN

SONGS AS ACTIONS a scene from a verse play by Peter Viereck HAN NIB A L& THE BONES OF ART a stroll in Mark Twain's pastures by Winfield rownley Scott LOVE ON THE ROAD a story by Edsel Ford MY AUNT OOMINGA a story ofChihuahua byAmado Muro SHORT LONG STORY by Robert A. Knudsen NINETEEN POEMS . Lucille Adler, Barwyn Browne, Stanley Cooperman Eiku, Antoni Gronowicz, AtiyQ Hasan, Peter Jackson Virginia ScottMiner, Marion Montgomery .Georgia C. Nicholas, Barbara Harr Overmyer Rosalee G. Porter, Poul Roche, Larry Rubin Martha Shaw, Sue Smart, Marvin Solomon Milton Speiser, Sanford V. Sternlicht BOOK REVIEWS INDEX TO VOLUME XXX ,S cellts .New .exlcoQaal1erl~· VOLUME xxx NUMBER 4 WINTER 1960..61 • ARTICLES MOTHER MEMORY. Sue Smart. 367 HANNIBAL & THE BONES OF ART. THE GHOST DANCE. Barwyn Browne. 368 Winfield Townley Scott. 8 33 THE LIONS. Milton Speiser. 37,0 STO,RIES. AT LAST. Eiku. 37J SHORT LoNG STORY. TRJPTYCH. Stanley Cooperman. ~72 Robert A. Knudsen. 358 HYMN To ~RES. Martha Shaw. 372 My AUNT DOMINGA.. Amado Muro. 359 EVENING WATCH. Sanford Sternlicht. 372 LoVE ON THE ROAD. Edsel Ford. ·377 WINTER BIRTH. Larry Rubin. 373 DRA·MA DRY 1hsA. Peter Jackson. 373 SONGS AS ACTIONS. Verse Play. INVOCATION. Georgia C. Nicholas. 373 Peter Viereck. 347 1 JOY. Antoni Gronowiczr 374 POETRY BLUE-BLACK SHELL, BLUE FUntER. CEREM9NY. Lucile Adler. 365 Marvin Solomon. 375 THE MODERNS. Atiya Hasan. 365 NEW YORK BLIZZARD. STRANGE PIPING. Virginia Scott Miner. 366 Paul Roche. 376 OUR GARDEN IN HAIKu. DEPARTMENTS Rosalee G. Porter. 366 A LETTER HOME. BOOKS. Thirty-five reviews. -

Notable Contributors to the North American Review

Notable Contributors to the North American Review AMERICAN WRITERS Stephen Dunn* Conrad Aiken* Washington Irving Margaret Atwood Joseph Auslander William Cullen Bryant Bobbie Ann Mason Robert Penn Warren* Ralph Waldo Emerson Maxine Hong Kingston Karl Shapiro* Henry Wadsworth Longfellow John Edgar Wideman William Stafford John Greenleaf Whittier Stuart Dybek Mona Van Duyn* Harriet Beecher Stowe James Tate* James Dickey James Russell Lowell Barry Lopez Philip Levine* Walt Whitman Annie Dillard* Mark Strand* Rebecca Harding Davis Scott Russell Sanders Charles Wright* Horatio Alger Yusef Komunyakaa* Ted Kooser Mark Twain Albert Goldbarth Billy Collins William Dean Howells T.C. Boyle Rita Dove* Henry James* Alberto Ríos Natasha Trethewey* Joel Chandler Harris Tony Hoagland Charlotte Perkins Gilman Louise Erdrich U.S. PRESIDENTS Hamlin Garland* Dean Young John Adams Edith Wharton* Ha Jin Thomas Jefferson Edith Hamilton Martín Espada Abraham Lincoln Mary Austin Madison Smart Bell Ulysses S. Grant Booth Tarkington* Diana Abu-Jaber James A. Garfield George Sterling Bob Hicok Benjamin Harrison Edwin Arlington Robinson* Antonya Nelson Grover Cleveland Theodore Dreiser Ray Gonzalez William McKinley Amy Lowell* Jennifer Egan* Woodrow Wilson Upton Sinclair* Steve Almond William H. Taft Sara Teasdale* C. Dale Young Theodore Roosevelt Margaret Widdemer* Aimee Bender Franklin D. Roosevelt Ezra Pound John Gould Fletcher* NOTABLE AMERICANS INTERNATIONAL Frank Luther Mott* William Ellery Channing CONTRIBUTORS Robert P. T. Coffin* Daniel Webster Victor Hugo -

History and Humanities Reader: the Modern World II 1850 to the Present

Oral Roberts University Digital Showcase College of Arts and Cultural Studies Faculty Research and Scholarship College of Arts and Cultural Studies 2020 History and Humanities Reader: The Modern World II 1850 to the Present Gary K. Pranger Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalshowcase.oru.edu/coacs_pub Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Pranger, Gary K., "History and Humanities Reader: The Modern World II 1850 to the Present" (2020). College of Arts and Cultural Studies Faculty Research and Scholarship. 12. https://digitalshowcase.oru.edu/coacs_pub/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Cultural Studies at Digital Showcase. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts and Cultural Studies Faculty Research and Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Showcase. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORAL ROBERTS UNIVERSITY HISTORY – HUMANITIES READER THE MODERN WORLD II 1850 TO THE PRESENT Gary K. Pranger, Editor and Contributor 1 THE MODERN WORLD II: 1850 To The Present TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 THE LATE 19TH CENTURY 1. THE VICTORIAN ERA G. Pranger 7 2 NATIONALISM G. Pranger 12 3. IMPERIALISM G. Pranger 35 4. 19th CENTURY PHILOSOPHERS David Ringer 41 5. REALISM IN LITERATURE David Ringer 78 6. IBSEN, STRINDBERG AND 19TH CENTURY DRAMA 92 7. IMPRESSIONISM TO EXPRESSIONISM 104 THE 20TH CENTURY 8. CAUSES & MEANING OF WORLD WAR I J. Franklin Sexton 122 9. WORLD WAR I Gary K. Pranger 129 10. FACISM G. Pranger 142 11. COMMUNISM: MARX TO LENIN AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION G. -

The Corruption of American Conservatism

The Corruption of American Conservatism Iskander Rehman December 2017 Cover photo credits: Jim Larkin/Shutterstock.com December 2017 THE CORRUPTION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM Iskander Rehman It is true that courtiers in America do not say ‘Sire’ and ‘Your Majesty’—a great and capital difference; but they speak constantly of the natural enlightenment of their master; they do not hold a competition on the question of knowing which one of the virtues of the prince most merits being admired; for they are sure that he possesses all the virtues, without having acquired them and so to speak without wanting to do so; they do not give them their wives and daughters so that he may deign to elevate them to the rank of their mistresses; but in sacrificing their opinions to him, they prostitute themselves. - Alexis de Tocqueville, On Democracy in America, Vol.I, Part 2, Chapter 7. n a sunny morning in January 1962, an to a crackpot fringe of “Commie-haunted apple editor, a philosopher and a presidential pickers and cactus drunks,” but also included Oaspirant huddled in a Florida hotel prominent Arizonians—some of whom had room. The topic of discussion was a deranged expressed sympathy for his candidacy. For candy manufacturer, Robert Welch. Welch, William F. Buckley and Russell Kirk, however, the a millionaire, was the head of the John Birch Birchers were a tumorous outgrowth of American Society, an extremist movement that trafficked in conservatism, and one that needed to be carefully anti-communist hysteria and absurd conspiracy excised. Buckley later recalled himself thinking, theories—most notably claiming that President “How can the John Birch Society be an effective Eisenhower had been a “conscious Communist political instrument while it is led by a man whose agent.”1 Troubled by the growing popularity of the views on current affairs are at so many critical movement, William F. -

Title of Thesis Or Dissertation, Worded

“THE STEP OF IRON FEET”: FORMAL MOVEMENTS IN AMERICAN WORLD WAR II POETRY by RACHEL LYNN EDFORD A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2011 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Rachel Lynn Edford Title: “The Step of Iron Feet”: Formal Movements in American World War II Poetry This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: Karen Jackson Ford Chairperson John Gage Member Paul Peppis Member Cecilia Enjuto Rangel Outside Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2011 ii © 2011 Rachel Lynn Edford iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Rachel Lynn Edford Doctor of Philosophy Department of English September 2011 Title: “The Step of Iron Feet”: Formal Movements in American World War II Poetry Approved: _______________________________________________ Karen Jackson Ford We have too frequently approached American World War II poetry with assumptions about modern poetry based on readings of the influential British Great War poets, failing to distinguish between WWI and WWII and between the British and American contexts. During the Second World War, the Holocaust and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki obliterated the line many WWI poems reinforced between the soldier’s battlefront and the civilian’s homefront, authorizing for the first time both civilian and soldier perspectives. Conditions on the American homefront—widespread isolationist and anti-Semitic attitudes, America’s late entry into the war, the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese internment, and the African American “Double V Campaign” to fight fascism overseas and racism at home—were just some of the volatile conditions poets in the US grappled with during WWII. -

The Concept of Man in the Poetry of Robert Frost

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1954 The Concept of Man in the Poetry of Robert Frost William W. Adams Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Adams, William W., "The Concept of Man in the Poetry of Robert Frost" (1954). Master's Theses. 893. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/893 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1954 William W. Adams THE CONCEPT OF MAN IN THE POETRY OF ROBERT FROST by William W. Adams A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree from Loyola University of Chicago. TABLE OF CONTENl'S Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION • . 1 Statement of thesis--Robert Frost's life and work--His oontemporaries' estimate--His development and change. II • THE INDIVIDUAL • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 11 Frost places the acoent on mants self-reliance--He sees men as indiv1duals--Man for him somehow is walled in and apart striving to maintain his human dignity come what may. III. NA.TURE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 26 This is the ultimately changless context for man- Frost sees nature as the farmer MUst--It is man's limit--Frast personifies nature--He relates man more directly to nature than to other men. -

Catholic Colonization of the American Right: Historical Overview Blandine Chelini-Pont

Catholic Colonization of the American Right: Historical Overview Blandine Chelini-Pont To cite this version: Blandine Chelini-Pont. Catholic Colonization of the American Right: Historical Overview. Marie GAYTE; Blandine CHELINI-PONT; Mark ROZELL. CATHOLICS AND US POLITICS AFTER THE 2016 ELECTIONS. UNDERSTANDING THE SWING VOTE, Palgrave, 2018, Studies in Reli- gions, Politics and Policy, 978-3-319-62262-0. 10.1007/978-3-319-62262-0_3. hal-02187925 HAL Id: hal-02187925 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02187925 Submitted on 19 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Catholic Colonization of the American Right: Historical Overview Blandine Chelini-Pont, Aix-Marseille University Catholic background, in the ideological building of the contemporary American right, seems to be a secondary issue in the history of the conservative movement. However, with very fine studies in recent years on the right-wing tendency of Catholic population or on the long lasting relationship between Catholics and political life1, this peculiar aspect