A Way of Happening Auden’S American Presence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET of the THIRTIES

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET OF THE THIRTIES THE coMPLETION OF JoHN LEHMANN's autobiography with I Am My Brother (1960), begun with The Whispering Gallery (1955), brings back to mind, among a score of other largely forgotten matters, the fact that there were angry young poets in England long before those of last year-or was it year before last? The most outspoken of the much earlier dissident young verse writers were probably the three who made up the so-called "Oxford group", W. ·H. Auden, Stephen Spender, and C. Day Lewis. (Properly speaking they were never a group in col lege, though they knew one ariother as undergraduates and were interested in one another's work.) Whether taken together or singly, .they differed markedly from the young poets who have recently been given the label "angry". What these latter day "angries" are angry about is difficult to determine, unless indeed it is merely for the sake of being angry. Moreover, they seem to have nothing con structive to suggest in cure of whatever it is that disturbs them. In sharp contrast, those whom they have displaced (briefly) were angry about various conditions and situations that they were ready and eager to name specifically. And, as we shall see in a moment, they were prepared to do something about them. What the angry young poets of Lehmann's generation were angry about was the heritage of the first World War: the economic crisis, industrial collapse, chronic unemployment, and the increasing tP,reat of a second World War. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

An Index to Alan Ansen's the Table Talk of W. H. Auden Edited By

An Index to Alan Ansen’s The Table Talk of W. H. Auden Edited by Nicholas Jenkins Index Compiled by Jacek Niecko A Supplement to The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter Number 20 • June 2000 Jacek Niecko is at work on a volume of conversations and interviews with W. H. Auden. Adams, Donald James 68, 115 Christmas Day 1941 letter to Aeschylus Chester Kallman 105 Oresteia 74 Collected Poems (1976) 103, 105, Akenside, Mark 53 106, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, Amiel, Henri-Frédéric 25 114, 116, 118 Andrewes, Lancelot 75 Collected Poetry 108 Meditations 75 Dark Valley, The 104 Sermons 75 Dog Beneath the Skin, The 51, 112 Aneirin Dyer’s Hand, The xiii, 100, 109, 111 Y Gododdin 108 “Easily, my dear, you move, easily Ann Arbor, Michigan 20, 107 your head” 106 Ansen, Alan ix-xiv, 103, 105, 112, 115, Enemies of a Bishop, The 22, 107 117 English Auden, The 103, 106, 108, Aquinas, Saint Thomas 33, 36 110, 112, 115, 118 Argo 54 Forewords and Afterwords 116 Aristophanes For the Time Being 3, 104 Birds, The 74 Fronny, The 51, 112 Clouds, The 74 “Greeks and Us, The” 116 Frogs, The 74 “Guilty Vicarage, The” 111 Aristotle 33, 75, 84 “Hammerfest” 106 Metaphysics 74 “Happy New Year, A” 118 Physics 74 “I Like It Cold” 115 Arnason Jon “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” xv, 70 Icelandic Legends 1 “In Search of Dracula” 106 Arnold, Matthew xv, 20, 107 “In Sickness and In Health” 106 Asquith, Herbert Henry 108 “In the Year of My Youth” 112 Athens, Greece 100 “Ironic Hero, The” 118 Atlantic 95 Journey to a War 105 Auden, Constance Rosalie Bicknell “Law Like Love” 70, 115 (Auden’s mother) 3, 104 Letter to Lord Byron 55, 103, 106, Auden, Wystan Hugh ix-xv, 19, 51, 99, 112 100, 103-119 “Malverns, The” 52, 112 “A.E. -

HARLEM in SHAKESPEARE and SHAKESPEARE in HARLEM: the SONNETS of CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, and GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2015 HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J. Leitner Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Leitner, David J., "HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 1012. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS by David Leitner B.A., University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, 1999 M.A., Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Department of English in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS By David Leitner A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Approved by: Edward Brunner, Chair Robert Fox Mary Ellen Lamb Novotny Lawrence Ryan Netzley Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 10, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF DAVID LEITNER, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in ENGLISH, presented on April 10, 2015, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

Naked Lunch for Lawyers: William S. Burroughs on Capital Punishment

Batey: Naked LunchNAKED for Lawyers: LUNCH William FOR S. Burroughs LAWYERS: on Capital Punishme WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT, PORNOGRAPHY, THE DRUG TRADE, AND THE PREDATORY NATURE OF HUMAN INTERACTION t ROBERT BATEY* At eighty-two, William S. Burroughs has become a literary icon, "arguably the most influential American prose writer of the last 40 years,"' "the rebel spirit who has witch-doctored our culture and consciousness the most."2 In addition to literature, Burroughs' influence is discernible in contemporary music, art, filmmaking, and virtually any other endeavor that represents "what Newt Gingrich-a Burroughsian construct if ever there was one-likes to call the counterculture."3 Though Burroughs has produced a steady stream of books since the 1950's (including, most recently, a recollection of his dreams published in 1995 under the title My Education), Naked Lunch remains his masterpiece, a classic of twentieth century American fiction.4 Published in 1959' to t I would like to thank the students in my spring 1993 Law and Literature Seminar, to whom I assigned Naked Lunch, especially those who actually read it after I succumbed to fears of complaints and made the assignment optional. Their comments, as well as the ideas of Brian Bolton, a student in the spring 1994 seminar who chose Naked Lunch as the subject for his seminar paper, were particularly helpful in the gestation of this essay; I also benefited from the paper written on Naked Lunch by spring 1995 seminar student Christopher Dale. Gary Minda of Brooklyn Law School commented on an early draft of the essay, as did several Stetson University colleagues: John Cooper, Peter Lake, Terrill Poliman (now at Illinois), and Manuel Ramos (now at Tulane) of the College of Law, Michael Raymond of the English Department and Greg McCann of the School of Business Administration. -

Everything Lost

Everything Lost Everything LosT THE LATIN AMERICAN NOTEBOOK OF WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS GENERAL EDITORS Geoffrey D. Smith and John M. Bennett VOLUME EDITOR Oliver Harris THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS / COLUMBUS Copyright © 2008 by the Estate of William S. Burroughs. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Burroughs, William S., 1914–1997. Everything lost : the Latin American notebook of William S. Burroughs / general editors: Geoffrey D. Smith and John M. Bennett ; introduction by Oliver Harris. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1080-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1080-5 (alk. paper) 1. Burroughs, William S., 1914–1997—Notebooks, sketchbooks, etc. 2. Burroughs, William S., 1914–1997— Travel—Latin America. I. Smith, Geoffrey D. (Geoffrey Dayton), 1948– II. Bennett, John M. III. Title. PS3552.U75E63 2008 813’.54—dc22 2007025199 Cover design by Fulcrum Design Corps, Inc . Type set in Adobe Rotis. Text design and typesetting by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanance of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.49-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 coNtents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION BY OLIVER HARRIS ix COMMENTS ON THE TEXT BY GEOFFREY D. SMITH xxvii NOTEBOOK FACSIMILE 1 TRANSCRIPT AND FAIR COPY (with notes and variant readings) 105 ABOUT THE EDITORS 217 acknoWledgments First and foremost, the editors wish to thank James Grauerholz, literary execu- tor of the William S. Burroughs estate, for permission to publish this seminal holograph notebook. -

Dana Young Archive Featuring Brion Gysin, Charles Henri Ford, Ira Cohen, Ray Johnson, David Rattray, Harold Norse, and the Bardo Matrix

Dana Young Archive Featuring Brion Gysin, Charles Henri Ford, Ira Cohen, Ray Johnson, David Rattray, Harold Norse, and the Bardo Matrix. [top] A portrait of Dana Young in front of an altar of candles, Kathmandu (date and photographer unknown). [bottom] Detail of Dana Young cover for Ira Cohen’s Poem for La Malinche (Bardo Matrix, ca. 1974) and [right] Dana Young print of Ira Cohen, “The Master & the Owl,” (date unknown). Dana Young (ca. 1948–1979) Dana Young was an essential member of the Kathmandu psychedelic expatriate community of poets, musicians, artists, and spiritual seekers in the 1970s. His poetry and shamanic art blended Eastern spiritual imagery with American pop and consumer culture. He was an active member of the Bardo Matrix collective and is best known for his book Opium Elementals (Bardo Matrix, 1976) that features his beautiful woodblock prints along with two poems by Ira Cohen. He contributed to several other Bardo Matrix publications including Cohen’s Blue Oracle broadside (1975), the frontispiece to Paul Bowles’ Next to Nothing (1976), and Ira Cohen and Roberto Francisco Valenza’s Spirit Catcher! broadside (1976). His artwork also appears in publications such as Montana Gothic (1974) and Ins and Outs (1978). Dana designed the logo (included in the archive) for John Chick’s Rose Mushroom club located at the end of Jhochhen Tole, known as “Freak Street,” in Kathmandu. Most recently, one of Dana Young’s wood block prints was featured on the album cover of the recent release of Angus MacLise's Dreamweapon II. Materials in the present collection comprise the archive of Dana Young supplemented with letters, photographs, and assorted items from the Ira Cohen archive via Richard Aaron, Am Here Books. -

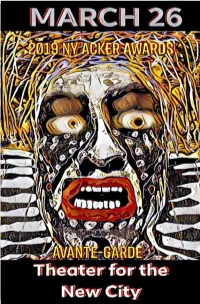

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

Guide to the Papers of the Summer Seminar of the Arts

Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Guide to the Papers of The Summer Seminar of the Arts Auburn University at Montgomery Library Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2 Biographical Information 3-4 Scope and Content Note 5 Arrangement 5-6 Inventory 6-24 1 Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Collection Summary Creator: Jack Mooney Title: Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Dates: ca. 1969-1983 Quantity: 9 boxes; 6.0 cu. ft. Identification: 2005/02 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: Jack Mooney donated the collection to the AUM Library in May 2005. Processing By: Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant (2005). Copyright Information: Copyright not assigned to the AUM Library. Restrictions Restrictions on access: There are no restrictions on access to these papers. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. 2 Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Biographical/Historical Information The Summer Seminar of the Arts was an annual arts and literary festival held in Montgomery from 1969 until 1983. The Seminar was part of the Montgomery Arts Guild, an organization which was active in promoting and sponsoring cultural events. Held during July, the Seminar hosted readings by notable poets, offered creative writing workshops, held creative writing contests, and featured musical performances. -

Spring 2009 Number 1 Special Issue a Publication of the Wallace Stevens Society, Inc

The Wallace Stevens Journal “The Less Legible Meanings of Sounds” The Wallace The Wallace Stevens Journal Vol. 33 No. 1 Spring 2009 Vol. Special Issue Wallace Stevens and “The Less Legible Meanings of Sounds” A Publication of The Wallace Stevens Society, Inc. Volume 33 Number 1 Spring 2009 The Wallace Stevens Journal Volume 33 Number 1 Spring 2009 Special Issue Wallace Stevens and “The Less Legible Meanings of Sounds” Edited by Natalie Gerber Contents Introduction —Natalie Gerber 3 Sound at an Impasse —Alan Filreis 15 Sound and Sensuous Awakening in Harmonium —Beverly Maeder 24 The Sound of the Queen’s Seemings in “Description Without Place” —Alison Rieke 44 The “Final Finding of the Ear”: Wallace Stevens’ Modernist Soundscapes —Peter Middleton 61 Weather, Sound Technology, and Space in Wallace Stevens —Sam Halliday 83 Wallace Stevens and the Spoken Word —Tyler Hoffman 97 Musical Transformations: Wallace Stevens and Paul Valéry —Lisa Goldfarb 111 Poems 129 Reviews 133 Current Bibliography 139 Cover Karhryn Jacobi The Tink-tonk of the Rain from “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven,” XIV The Wallace Stevens Journal EDITOR John N. Serio POETRY EDITOR ART EDITOR BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Joseph Duemer Kathryn Jacobi George S. Lensing EDITORI A L ASSIST A NTS EDITORI A L BO A RD William H. Duryea Milton J. Bates George S. Lensing Maureen Kravec Jacqueline V. Brogan James Longenbach Hope Steele Robert Buttel Glen MacLeod Eleanor Cook Marjorie Perloff TECHNIC A L ASSIST A NT Bart Eeckhout Joan Richardson Jeff Rhoades Alan Filreis Melita Schaum B. J. Leggett Lisa M. Steinman The Wallace Stevens Society, Inc. -

City Lights Pocket Poets Series 1955-2005: from the Collection of Donald A

CITY LIGHTS POCKET POETS SERIES 1955-2005: FROM THE COLLECTION OF DONALD A. HENNEGHAN October 2005 – January 2006 1. Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Pictures of the Gone World. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1955. Number One 2. Kenneth Rexroth, translator. Thirty Spanish Poems of Love and Exile. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1956. Number Two 3. Kenneth Patchen. Poems of Humor & Protest. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1956. Number Three 4. Allen Ginsberg. Howl and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1956. Number Four 5. Marie Ponsot. True Minds. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1956. Number Five 6. Denise Levertov. Here and Now. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1957. Number Six 7. William Carlos Williams. Kora In Hell: Improvisations. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1957. Number Seven 8. Gregory Corso. Gasoline. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1958. Number Eight 9. Jacques Prévert. Selections from Paroles. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1958. Number Nine 10. Robert Duncan. Selected Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1959. Number Ten 11. Jerome Rothenberg, translator. New Young German Poets. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1959. Number Eleven 12. Nicanor Parra. Anti-Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1960. Number Twelve 13. Kenneth Patchen. The Love Poems of Kenneth Patchen. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1961. Number Thirteen 14. Allen Ginsberg. Kaddish and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1961. Number Fourteen OUT OF SERIES Alain Jouffroy. Déclaration d’Indépendance. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1961. Out of Series 15. Robert Nichols. Slow Newsreel of Man Riding Train. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1962. -

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980 Robert L. Richardson, Jr. A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by, Michael H. Hunt, Chair Richard Kohn Timothy McKeown Nancy Mitchell Roger Lotchin Abstract Robert L. Richardson, Jr. Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1985 (Under the direction of Michael H. Hunt) This dissertation examines the origins and evolution of neoconservatism as a philosophical and political movement in America from 1945 to 1980. I maintain that as the exigencies and anxieties of the Cold War fostered new intellectual and professional connections between academia, government and business, three disparate intellectual currents were brought into contact: the German philosophical tradition of anti-modernism, the strategic-analytical tradition associated with the RAND Corporation, and the early Cold War anti-Communist tradition identified with figures such as Reinhold Niebuhr. Driven by similar aims and concerns, these three intellectual currents eventually coalesced into neoconservatism. As a political movement, neoconservatism sought, from the 1950s on, to re-orient American policy away from containment and coexistence and toward confrontation and rollback through activism in academia, bureaucratic and electoral politics. Although the neoconservatives were only partially successful in promoting their transformative project, their accomplishments are historically significant. More specifically, they managed to interject their views and ideas into American political and strategic thought, discredit détente and arms control, and shift U.S. foreign policy toward a more confrontational stance vis-à-vis the Soviet Union.