Chaenomeles Japonica)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, Implementation and Sustainability

Department of Political and Social Sciences Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, Implementation and Sustainability Igor Guardiancich Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Florence, October 2009 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Department of Political and Social Sciences Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, Implementation and Sustainability Igor Guardiancich Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Examining Board: Prof. Martin Rhodes, University of Denver/formerly EUI (Supervisor) Prof. Nicholas Barr, London School of Economics Prof. Martin Kohli, European University Institute Prof. Tine Stanovnik, Univerza v Ljubljani © 2009, Igor Guardiancich No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Guardiancich, Igor (2009), Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, implementation and sustainability European University Institute DOI: 10.2870/1700 Guardiancich, Igor (2009), Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, implementation and sustainability European University Institute DOI: 10.2870/1700 Acknowledgments No PhD dissertation is a truly individual endeavour and this one is no exception to the rule. Rather it is a collective effort that I managed with the help of a number of people, mostly connected with the EUI community, to whom I owe a huge debt of gratitude. In particular, I would like to thank all my interviewees, my supervisors Prof. Martin Rhodes and Prof. Martin Kohli, as well as Prof. Tine Stanovnik for continuing intellectual support and invaluable input to the thesis. -

Assessing Macroeconomic Vulnerability in Central Europe

ab0cd Assessing macroeconomic vulnerability in central Europe by Libor Krkoska Abstract The central European transition-accession countries experienced several periods of macroeconomic vulnerability since the end of output declines in early 1990s. Some notable periods, which resulted in a necessity to implement extensive stabilisation measures, are March 1995 in Hungary, May 1997 in the Czech Republic, and September 1998 in the Slovak Republic. This paper shows that the standard early warning indicators provided useful information on macroeconomic vulnerability prior to the crises in central Europe, although this information had been mainly indicative; that is, early warning indicators would not have allowed one to predict the crises and their timing. In particular, the growing gap between current account deficit and foreign direct investment (FDI) in all the analysed countries provided clear early warning of subsequent economic turbulence. JEL classification: F30, O57, P27. Keywords: Macroeconomic vulnerability, currency crisis, early warning. Address for correspondence: Office of the Chief Economist, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, One Exchange Square, London EC2A 2JN, United Kingdom. Telephone: +44 20 7338 6710; Fax: +44 20 7338 6110; e-mail: [email protected] I would like to thank Nevila Konica and Peter Sanfey for many helpful comments. Numerous discussions with Julian Exeter on early warning systems for transition economies are gratefully acknowledged. The author is an Economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The working paper series has been produced to stimulate debate on the economic transformation of central and eastern Europe and the CIS. Views presented are those of the authors and not necessarily of the EBRD. -

Garden Mastery Tips March 2006 from Clark County Master Gardeners

Garden Mastery Tips March 2006 from Clark County Master Gardeners Flowering Quince Flowering quince is a group of three hardy, deciduous shrubs: Chaenomeles cathayensis, Chaenomeles japonica, and Chaenomeles speciosa. Native to eastern Asia, flowering quince is related to the orchard quince (Cydonia oblonga), which is grown for its edible fruit, and the Chinese quince (Pseudocydonia sinensis). Flowering quince is often referred to as Japanese quince (this name correctly refers only to C. japonica). Japonica is often used regardless of species, and flowering quince is still called Japonica by gardeners all over the world. The most commonly cultivated are the hybrid C. superba and C. speciosa, not C. japonica. Popular cultivars include ‘Texas Scarlet,’ a 3-foot-tall plant with red blooms; ‘Cameo,’ a double, pinkish shrub to five feet tall; and ‘Jet Trail,’ a white shrub to 3 feet tall. Flowering quince is hardy to USDA Zone 4 and is a popular ornamental shrub in both Europe and North America. It is grown primarily for its bright flowers, which may be red, pink, orange, or white. The flowers are 1 to 2 inches in diameter, with five petals, and bloom in late winter or early spring. The glossy dark green leaves appear soon after flowering and turn yellow or red in autumn. The edible quince fruit is yellowish-green with reddish blush and speckled with small dots. The fruit is 2 to 4 inches in diameter, fragrant, and ripens in fall. The Good The beautiful blossoms of flowering quince Flowering quince is an easy-to-grow, drought-tolerant shrub that does well in shady spots as well as sun (although more sunlight will produce better flowers). -

Chaenomeles Speciosa) in the Naxi and Tibetan Highlands of NW Yunnan, China

Cultural and Ecosystem Services of Flowering Quince (Chaenomeles speciosa) in the Naxi and Tibetan Highlands of NW Yunnan, China. Authors: Lixin Yang, Selena Ahmed, John Richard Stepp, Yanqinag Zhao, Ma Jun Zeng, Shengji Pei, Dayuan Xue, and Gang Xu The final publication is available at Springer via https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-015-9318-7. Yang, Lixin, Selena Ahmed, John Richard Stepp, Yanqinag Zhao, Ma Jun Zeng, Shengji Pei, Dayuan Xue, and Gang Xu. “Cultural Uses, Ecosystem Services, and Nutrient Profile of Flowering Quince (Chaenomeles Speciosa) in the Highlands of Western Yunnan, China.” Economic Botany 69, no. 3 (September 2015): 273–283. doi:10.1007/s12231-015-9318-7. Made available through Montana State University’s ScholarWorks scholarworks.montana.edu Cultural Uses, Ecosystem Services, and Nutrient Profile Chaenomeles speciosa of Flowering Quince ( ) in the Highlands 1 of Western Yunnan, China 2,3 3,4 ,3,5 6 LIXIN YANG ,SELENA AHMED ,JOHN RICHARD STEPP* ,YANQINAG ZHAO , 7 2 ,3 2 MA JUN ZENG ,SHENGJI PEI ,DAYUAN XUE* , AND GANG XU 2State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Plant Resources in West China, Kunming Institutes of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, China 3College of Life and Environmental Science, Minzu University of China, Beijing, China 4Department of Health and Human Development, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, USA 5Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA 6College of Forestry and Vocational Technology in Yunnan, Kunming, China 7Southwest Forestry University, Bailongshi, Kunming, China *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Introduction ample light but is tolerant of partial shade. -

Database on Forest Disturbances in Europe (DFDE)- Technical Report History, State of the Art, and Future Perspectives

Database on Forest Disturbances in Europe (DFDE)- Technical report History, State of the Art, and Future Perspectives Marco Patacca, Mart-Jan Schelhaas, 2020 Sergey Zudin, Marcus Lindner Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 2 1. Historical Framework – The need for update ................................................................................. 3 2. Definitions ....................................................................................................................................... 4 3. The New Database .......................................................................................................................... 6 Database Outline ................................................................................................................................ 6 Technical implementation .................................................................................................................. 6 4. Guidelines for data preparation and uploading .............................................................................. 7 Data Structure & Preparation ............................................................................................................. 8 Data Uploading ................................................................................................................................. 10 Data Uploading Examples ............................................................................................................ -

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1 Authors: Jiang, Wei, He, Hua-Jie, Lu, Lu, Burgess, Kevin S., Wang, Hong, et. al. Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 104(2) : 171-229 Published By: Missouri Botanical Garden Press URL: https://doi.org/10.3417/2019337 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Annals-of-the-Missouri-Botanical-Garden on 01 Apr 2020 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS Volume 104 Annals Number 2 of the R 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden EVOLUTION OF ANGIOSPERM Wei Jiang,2,3,7 Hua-Jie He,4,7 Lu Lu,2,5 POLLEN. 7. NITROGEN-FIXING Kevin S. Burgess,6 Hong Wang,2* and 2,4 CLADE1 De-Zhu Li * ABSTRACT Nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in root nodules is known in only 10 families, which are distributed among a clade of four orders and delimited as the nitrogen-fixing clade. -

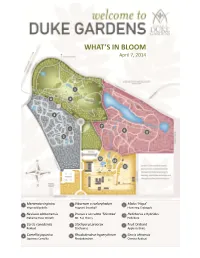

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

The Catholic Church and the Europeanization Process

No. 32 TRONDHEIM STUDIES ON EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES & SOCIETIES DAG OLE HUSEBY THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EUROPEANIZATION PROCESS October 2010 Dag Ole Huseby wrote his Master’s thesis at the Department of Sociology and Political Science of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. The present book is a thoroughly revised version of the thesis. © 2010 Dag Ole Huseby and the Program on East European Cultures and Societies, a program of the Faculties of Humanities and Social Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. ISBN 978-82-995792-8-5 ISSN 1501-6684 Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies Editors: György Péteri and Sabrina P. Ramet Editorial Board: Trond Berge, Tanja Ellingsen, Knut Andreas Grimstad, Arne Halvorsen We encourage submissions to the Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies. Inclusion in the series will be based on anonymous review. Manuscripts are expected to be in English and not to exceed 150 double spaced pages in length. Postal address for submissions: Editor, Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies, Department of History, NTNU, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway. For more information on PEECS and TSEECS, visit our web-site at http://www.hf.ntnu.no/peecs/home/ The Catholic Church and the Europeanization Process. An Empirical Analysis of EU Democratic Conditionality and Anti-Discrimination Protection in Post-Communist Poland and Croatia by Dag Ole Huseby Acknowledgments I am deeply grateful for the patience and support Professor Sabrina P. Ramet has shown while I was working on this piece. Her academic knowledge, fine tuned eye for detail, constructive criticism and numerous advices has proven invaluable for the final result. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnation Compaigr 300 North Zed; Road, Ann Aiiwr Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 ENTREPRENEURIAL CLASS IN POLAND: RECRUITMENT PATTERNS AND FORMATION PROCESSES IN THE POST-COMMUNIST SYSTEM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ptiilosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State Utiiversity By Elizabeth Ann Osborn. -

Chaenomeles Spp. - Flowering Quince (Rosaceae) ------Chaenomeles Is a Functional Flowering Hedge, Border, Twigs Or Specimen Shrub That Can Be Used Near Buildings

Chaenomeles spp. - Flowering Quince (Rosaceae) ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chaenomeles is a functional flowering hedge, border, Twigs or specimen shrub that can be used near buildings. -buds small and reddish in color The major appeal of Flowering Quince is its showy -lightly armed (terminal and axillary spines) but brief flowering period. The rest of the year it’s a -young bark is reddish and cherry-like utilitarian thorny shrub with limited aesthetic Trunk attributes. -gray brown -many small diameter stems closely crowded, arising FEATURES from the ground Form -large shrubs USAGE 2-6' tall Function -vased shaped -sun tolerant, long-lived shrub habit with -useful as a hedge or barrier many small Texture diameter -medium in foliage and when bare stems Assets -1:1 height to -urban tolerant width ratio -withstand severe pruning -rapid growth -drought tolerant Culture -early spring flowers -full sun -dense growth and long-lived -adaptable to a wide range of soil conditions -lightly armed for effective "crowd control" -thrives under stressful conditions Liabilities -moderate availability -poor autumn color Foliage -trash can accumulate among its many small diameter -alternate, lanceolate stems (maintenance headache) -serrate margins -prone to cosmetic damage by insects -somewhat leathery -sheds foliage in summer in response to drought or -to 4" long disease pressure -leafy, kidney-shaped stipules (an ID feature) Habitat -summer color is dense medium green and attractive, -Zones 4 to 8, depending on species new growth often bronze -Native to the Orient (China, Japan) -autumn color yellowish green SELECTIONS Alternates -urban tolerant shrub with vase-shaped winter form (e.g. Berberis thunbergii, Berberis x mentorensis, Spiraea nipponica 'Snowmound' etc.) -early spring flowering shrubs (e.g. -

Management of Japanese Quince (Chaenomeles Japonica) Orchards

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Epsilon Open Archive Management of Japanese Quince (Chaenomeles japonica) Orchards Management of Japanese Quince (Chaenomeles japonica) Orchards D. Kviklysa*, S. Ruisab, K. Rumpunenc aLithuanian Institute of Horticulture, Babtai, Lithuania b Dobele Horticultural Plant Breeding Experimental Station, Dobele, Latvia cBalsgård–Department of Horticultural Plant Breeding, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Kristianstad, Sweden *Correspondence to [email protected] SUMMARY In this paper, advice for establishment and management of Japanese quince (Chaenomeles japonica) orchards is summarised. Japanese quince is a minor fruit crop in Latvia and Lithuania, currently being developed by plant breeding research. Preferences for site and soil are discussed and recommendations for planting and field management are proposed. INTRODUCTION Among the four known Chaenomeles species native to China, Tibet and Japan, Japanese quince (Chaenomeles japonica) is the species best adapted to the North European climate and it has been intro- duced as a minor fruit crop in Latvia and Lithuania (Rumpunen 2002, Tiits 1989, Tics 1992). At present, we are aware of only one active plant breeding programme that is aimed at improving Japanese quince as a fruit crop. This programme is being jointly conducted by the Department of Plant Biology, Helsinki University, Finland; Dobele Horticultural Plant Breeding Experimental Station, Latvia; the Lithuanian Institute of Horticulture, Lithuania and Balsgård–Department of Horticultural Plant Breeding, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Sweden (Rumpunen 2002). As a first step to improve Japanese quince, phenotypic selection has taken place in orchards in Latvia and Lithuania. Superior selections have been cloned and planted in comparative field trials in Finland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania and Sweden. -

Pathogens on Japanese Quince (Chaenomeles Japonica) Plants

Pathogens on Japanese Quince (Chaenomeles japonica) Plants Pathogens on Japanese Quince (Chaenomeles japonica) Plants I. Norina, K. Rumpunenb* aDepartment of Crop Science, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, Sweden Present address: Kanslersvägen 6, 237 31 Bjärred, Sweden bBalsgård–Department of Horticultural Plant Breeding, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Kristianstad, Sweden *Correspondence to [email protected] SUMMARY In this paper, a survey of pathogens on Japanese quince (Chaenomeles japonica) plants is reported. The main part of the study was performed in South Sweden, in experimental fields where no pesticides or fungicides were applied. In the fields shoots, leaves, flowers and fruits were collected, and fruits in cold storage were also sampled. It was concluded that Japanese quince is a comparatively healthy plant, but some fungi were identified that could be potential threats to the crop, which is currently being developed for organic growing. Grey mould, Botrytis cinerea, was very common on plants in the fields, and was observed on shoots, flower parts, fruits in all stages and also on fruits in cold storage. An inoculation experiment showed that the fungus could infect both wounded and unwounded tissue in shoots. Studies of potted plants left outdoors during winter indicated that a possible mode of infection of the shoots could be through persist- ing fruits, resulting in die-back of shoots. Fruit spots, brown lesions and fruit rot appeared in the field. Most common were small red spots, which eventually developed into brown rots. Fungi detected in these spots were Septoria cydoniae, Phlyctema vagabunda, Phoma exigua and Entomosporium mespili. The fact that several fungi were con- nected with this symptom indicates that the red colour may be a general response of the host, rather than a specific symptom of one fungus.