Otara, in Manukau City, New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.2 the MONARCHY Republican Sentiment Among New Zealand Voters, Highlighting the Social Variables of Age, Gender, Education

2.2 THE MONARCHY Noel Cox and Raymond Miller A maturing sense of nationhood has caused some to question the continuing relevance of the monarchy in New Zealand. However, it was not until the then prime minister personally endorsed the idea of a republic in 1994 that the issue aroused any significant public interest or debate. Drawing on the campaign for a republic in Australia, Jim Bolger proposed a referendum in New Zealand and suggested that the turn of the century was an appropriate time symbolically for this country to break its remaining constitutional ties with Britain. Far from underestimating the difficulty of his task, he readily conceded that 'I have picked no sentiment in New Zealand that New Zealanders would want to declare themselves a republic'. 1 This view was reinforced by national survey and public opinion poll data, all of which showed strong public support for the monarchy. Nor has the restrained advocacy for a republic from Helen Clark, prime minister from 1999, done much to change this. Public sentiment notwithstanding, a number of commentators have speculated that a New Zealand republic is inevitable and that any move in that direction by Australia would have a dramatic influence on public opinion in New Zealand. Australia's decision in a national referendum in 1999 to retain the monarchy raises the question of what effect, if any, that decision had on opinion on this side of the Tasman. In this chapter we will discuss the nature of the monarchy in New Zealand, focusing on the changing role and influence of the Queen's representative, the governor-general, together with an examination of some of the factors that might have an influence on New Zealand becoming a republic. -

The Interface Between Aboriginal People and Maori/Pacific Islander Migrants to Australia

CUZZIE BROS: THE INTERFACE BETWEEN ABORIGINAL PEOPLE AND MAORI/PACIFIC ISLANDER MIGRANTS TO AUSTRALIA By James Rimumutu George BA (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Newcastle March 2014 i This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: Date: ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors, Professor John Maynard and Emeritus Professor John Ramsland for their input on this thesis. Professor Maynard in particular has been an inspiring source of support throughout this process. I would also like to give my thanks to the Wollotuka Institute of Indigenous Studies. It has been so important to have an Indigenous space in which to work. My special thanks to Dr Lena Rodriguez for having faith in me to finish this thesis and also for her practical support. For my daughter, Mereana Tapuni Rei – Wahine Toa – go girl. I also want to thank all my brothers and sisters (you know who you are). Without you guys life would not have been so interesting growing up. This thesis is dedicated to our Mum and Dad who always had an open door and taught us to be generous and to share whatever we have. -

Freshwater Report Card

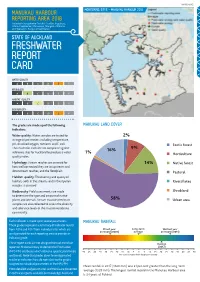

19-PRO-0142 MANUKAU HARBOUR MONITORING SITES – MANUKAU HARBOUR 2018 REPORTING AREA 2018 Includes Maungakiekie-Tamaki, Franklin, Papakura, Ōtara-Papatoetoe, Manurewa, Mangere-Otahuhu and Waitakere Ranges Local Boards STATE OF AUCKLAND FRESHWATER REPORT CARD WATER QUALITY A B C D E F HYDROLOGY A B C D E F HABITAT QUALITY A B C D E F BIODIVERSITY A B C D E F The grades are made up of the following MANUKAU LAND COVER indicators: Water quality: Water samples are tested for 2% a range of parameters including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrients and E. coli. Exotic forest The results for each site are compared against 16% 9% reference sites for Auckland to produce a water 1% Horticulture quality index. Hydrology: Stream reaches are assessed for 14% Native forest how well connected they are to upstream and downstream reaches, and the floodplain. Pastoral Habitat quality: The diversity and quality of habitats both in the streams and in the riparian Rivers/lakes margins is assessed. Biodiversity: Field assessments are made Shrubland to determine the type and amount of native plants and animals. Stream macroinvertebrate 58% Urban area samples are also collected to assess the diversity and tolerance levels of the macroinvertebrate community. Each indicator is made up of several parameters. MANUKAU RAINFALL These grades represent a summary of indicator results from 2016 and 2017 from individual sites which are Driest year Wettest year on record (2002) on record (2011) amalgamated for each reporting area to provide an indicator grade. These report cards are not designed to track trends or Rainfall report on National Policy Statement for Freshwater (2017) (NPS-FM) attributes which relate to specific parameters and bands. -

Feilding Public Library Collection

Object ID Begins with "2009.102" 14/06/2020 Matches 4033 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location P 2009.102.01.01 Manchester Street School, Feilding. Primer 2-3 1939. Grouped Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive against a fence with trees and houses in the background. Print, Photographic Front Row L to R: eighth girl - Betty Doughty, last girl - June Wells. P 2009.102.01.02 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School Std 4 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.03 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School F 1-2 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.04 Studio photo Manchester Street School Basketball A Team 1939 Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.05 Manchester Street School Basketball B Team 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.06 Manchester Street School Prefects 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.07 Manchester Street School 1st XV 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.08 Manchester Street School Special Class 1940 Grouped against a Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive fence with trees and houses in the background Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.09 Manchester Street School -

2009 Annual Report

2009 WIDER IMPACT, COMMUNITY CONTRIBUTION New Zealand’s Mäori Centre of Research Excellence www.maramatanga.ac.nz ISSN 1176-8622 © Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga New Zealand’s Mäori Centre of Research Excellence CONTACTS ko te pae tawhiti Postal Address Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga arumia kia tata Waipapa Marae Complex The University of Auckland ko te pae tata whakamaua Private Bag 92019 Auckland Mail Centre kia puta i te wheiao Auckland 1142 New Zealand ki te ao märama Physical Address Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga seek to bring the Rehutai Building 16 Wynyard Street distant horizon closer The University of Auckland Auckland but the closer horizon, grasp it New Zealand so you may emerge from darkness www.maramatanga.ac.nz [email protected] into enlightenment T +64 9 373 7599 ext 84220 F +64 9 373 7928 2009 HIGHLIGHTS 2009 saw many successes in delivering on the CoRE’s vision for positive social transformation, including: Publication of five academic journals of Mäori and indigenous writing, 41 peer-reviewed articles, 13 research reports, three book chapters and 65 conference papers or presentations Continued promotion of greater Mäori involvement in science with the launch of science monograph Te Ara Pütaiao – Mäori Insights in Science, prompting wide media and community interest in Mäori achievements, challenges and opportunities to contribute more fully to scientific advances The launch of our largest research programme, focusing on achieving research outcomes with long term benefits and confirmation of high-calibre independent advisory boards -

Annual Report 2014

www.selwyncare.org.nz Annual Report 2014 We commemorated 60 years of Our Parish Partnership service of Selwyn Village and Programme continued to go also celebrated our inaugural from strength-to-strength with The Year in Review Founders’ Day, a tribute to the opening of new Selwyn Selwyn’s founding fathers Centres, enabling us to expand and all those who have since our charitable outreach to benefit contributed to our ongoing greater numbers of older people mission to provide quality in the community. Highlights services for ageing people. Our volunteer programme was of 2014 The first phase of our ten year re-energised; quality placements Growth Plan got underway, are now available that are of which will see us implement a immense benefit to those for programme of redevelopment whom we care and worthy of the and expansion to deliver talented volunteers who help contemporary new village make every day a special day for environments and superior our residents. customer care. We held a number of important Work commenced on a 57-unit training events, conferences independent living apartment and experiential workshops for building at Selwyn Village, our clinicians and caregivers, and we announced plans village chaplains, Selwyn Centre to build exciting new care coordinators and others from facilities, resident community the wider aged care sector. Such amenities and a greater range events enable participants to Contents of independent living units at a upskill and reflect on the quality number of our villages. of the services they provide. The Year in Review 1 The prestigious five storey, The Spiritual and Cultural 2 Chair’s Report 56-unit Reeves Apartments Advisory Group and Clinical 4 Chief Executive Officer’s Report (named in honour of the late Governance Group were Sir Paul Reeves) opened at established to review our 6 Charity Selwyn Heights, showcasing practices in areas that are 8 Learning the latest thinking in retirement significant to the wellbeing and 10 Community accommodation and further experience of our residents and extending our market appeal. -

Policy Design and Māori Development in Aotearoa New Zealand

Accounting for Diversity: Policy Design and Māori Development in Aotearoa New Zealand Prepared by Dena Ringold With funding from the sponsors of the Ian Axford Fellowship in Public Policy July 2005 © Fulbright New Zealand 2005 ISBN 0-437-10213-7 i The Ian Axford Fellowships in Public Policy We acknowledge and thank the following corporate and government sponsors that support the programme: • ERMA New Zealand • LEK Consulting • The Department of Internal Affairs • The Department of Labour • The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet • The Ministry for the Environment • The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry • The Ministry of Economic Development • The Ministry of Education • The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade • The Ministry of Health • The Ministry of Justice • The Ministry of Research, Science and Technology • The Ministry of Social Development • The State Services Commission • The Treasury The Ian Axford Fellowships were named in honour of Sir Ian Axford, a New Zealand astrophysicist and space scientist. Since his education in New Zealand, England and later at Cornell University and the University of California, Sir Ian has been closely involved in the planning of several space missions, notably the Voyager probes to the outer planets. Since 1974, Sir Ian has been director of the Max Planck Institute of Aeronomy in Germany. He is the recipient of many notable science awards and was named “New Zealander of the Year” for 1995. In the world of space science, Sir Ian has emerged as one of the great thinkers and communicators, and a highly respected and influential administrator. Currently, he is working to create the first mission to interstellar space with the Voyager spacecraft. -

Words That Make Worlds. Arguments That Change Minds. Ideas That Illuminate. We Publish Books That Make a Difference

AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY PRESS — 2012 CATALOGUE Words that make worlds. Arguments that change minds. Ideas that illuminate. We publish books that make a difference. Summer 2012 BA: AN INSIDER’S GUIDE Rebecca Jury BA: An Insider’s Guide is the essential book for all those considering study or about to embark on their arts degree. In 10 steps, Jury introduces readers to everything from choosing courses (just like putting together a personalised gourmet sandwich), setting up a study space and doing part-time work to turning up at lectures and tutorials and actually reading readings. In particular, she focuses on planning, work–life balance, study habits, succeeding at essays and exams and sorting out a life afterwards. Recently emerged from the maelstrom of university, Jury offers the inside word on doing well there. Rebecca Jury graduated with a BA (English and Mass Communication) from Canterbury University in 2008. Her grade average was excellent! Since completing her degree she has worked as a university tutor, a youth counsellor and a high-school teacher. February 2012, 190 x 140 mm, 200 pages Paperback, 978 1 86940 577 9, $29.99 2/3 Summer 2012 BEAUTIES OF THE OCTAGONAL POOL Gregory O’Brien In an eight-armed embrace, Beauties of the Octagonal Pool collects poems written from and out of a variety of times, locations and experiences. O’Brien’s poems have a thoughtful musicality, a shambling romance, a sense of humour, an eye on the horizon. On Raoul Island we meet a mechanical rat; on Waiheke, the horses of memory thunder down the course; and in Doubtful Sound, the first guitar music heard in New Zealand spills over the waves . -

Waitangi Tribunal Manukau Report (1985)

MANUKAU REPORT WAI 8 WAITANGI TRIBUNAL 1985 W AITANGI TRIBUNAL LIBRARY REPORT OF THE WAITANGI TRIBUNAL ON THE MANUKAU CLAIM (WAI-8) WAITANGI TRIBUNAL DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE WELLINGTON NEW ZEALAND July 1985 Original cover design by Cliff Whiting, invoking the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the consequent development of Maori-Pakeha history interwoven in Aotearoa, in a pattern not yet completely known, still unfolding. National Library of New Zealand Cataloguing-in-Publication data New Zealand. Waitangi Tribunal. Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on the Manukau claim (Wai 8). 2nd ed. Wellington , N.Z.: The Tribunal, 1989. 1 v. (Waitangi Tribunal reports, 0113-4124) "July 1985." First ed. published in 1985 as: Finding of the Waitangi Tribunal on the Manukau claim. ISBN 0-908810-06-7 1. Manukau Harbour (N.Z.)--Water-rights. 2. Maoris--Land tenure. 3. Waitangi, Treaty of, 1840. I. Title. II. Series: Waitangi Tribunal reports; 333.91170993111 First published 1985 by the Government Printer Wellington, New Zealand Second edition published 1989 by the Waitangi Tribunal Department of Justice Wellington, New Zealand Crown copyright reserved Waitangi Tribunal Reports ISSN 0113-4124 Manukau Report (Wai-8) ISBN 0-908810-06-7 Typeset, printed and bound by the Government Printing Office Wellington, New Zealand ii NOT FOR PUBLIC RELEASE WAI-8 BEFORE 9.30 P.M. TUESDAY, 30 JULY 1985 IN THE MATTER of a Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 IN THE MATTER of a claim by NGANEKO MINHINNICK and Te Puaha ki Manuka concerning Manukau Harbour and environs FINDING OF THE -

The Sebel Auckland Manukau

THE SEBEL AUCKLAND MANUKAU Discover the perfect mix of independent space and exceptional service at Manukau City’s newest upscale hotel, The Sebel Auckland Manukau. WELCOME LOCATION Positioned in the heart of Manukau’s bustling centre From its perfect vantage point, the hotel allows you and a short drive from the airport, The Sebel to discover the best of the area including Rainbow’s Auckland Manukau is a stylish getaway located just End, Butterfly Creek, Westfield Mall, Vector Wero 22 kilometres from the Auckland CBD. Whitewater Park and Vodafone Events Centre. Ideal for both business and leisure travellers, Auckland’s main arterial route, the Southern The Sebel Auckland Manukau offers unforgettable Motorway is a 2-minute drive away and both the experiences, a modern design and personalised International and Domestic Airports are located service. within 10 kilometres from the hotel. BOTANY RES S TREET IAN S HAW RES PARK DOW NS RES RES RES Edgewater MATERNITY UNIT HOW ICK K R E N T A R V G M RIVERHILLS L R D A H D I O A A U M V COUNTRY L I L T R R S T Z L E E G W N V B N L N D I E R L O D L T E I P G A I College R S N S D M G A W R O B A L E O L U A E O T L N D A O O O S G R PARK U I E P O W A N P A N A Y d A R O U W I W CLUB L M E Y N R A C ' O EF P T R K S C S HEN Y U E Y A A R C A R G P O R L N S A M C E U N F O E I G R U T I N V d V L R T L E Y D A Y P A R E L O I L W P I A E A L L S D K N R D L E H GOLFLANDS R H U O O A C O L E E H S Y N L P T D I P H R D C R H L R O H R T U E A X C T T RES R D K T N RES E K U E " T O T V A D E -

To Manukau Centre Via Mangere East and Papatoetoe to Otahuhu

Rd Panmure y nd Bridge to Otahuhu • Downtown to Manukau Centre w Primary Irela r ve Ri via Papatoetoe and Mangere East via Mangere East and Papatoetoe on H aki Panmure Rd m a Basin anga T B rose llingt ur ai Pen R e Pak l ey R ey d St Kentigern Mt Wellington W College d t R d Countdown anga M ur Waipuna Rd Pak Manukau Papatoetoe Customs St Papatoetoe P ri Centre Town Hall Transfer Otahuhu Customs St East Otahuhu Transfer Otahuhu Town Hall Manukau ce Cr Route (Stop 6921) (Stop 6525) Otahuhu at Otahuhu (Stop 8094) East Route (Stop 7019) (Stop 8099) at Otahuhu (Stop 8099) (Stop 6520) Centre Sylvia Park 10 Primary Sylvia Park R Monday to Friday 428 Monday to Friday 428 ee d ves Rd R Riverina Sou Mt th Sylvia Park School 10 Ti ys e Pl d rn den M Wel Shopping Bow R U AM 428 5.30 5.37 5.55 471 6.05 6.41 AM --428 6.40 6.57 7.11 ot akau Dr orw Centre ay l 428 6.00 6.07 6.30 473 6.35 7.19 497 6.25 7.00 428 7.10 7.32 7.46 i r ng D mow C G Hamlins le a C reat Hill t rb 428 6.30 6.37 7.00 473 7.05 7.58 471 6.45 7.25 428 7.40 8.06 8.20 o T ine R a n r Pl bado m S Hig Ga ou Rd 428 7.00 7.10 7.32 471 7.40 8.46 497 7.15 8.00 428 8.10 8.41 8.55 Rd a rk ahan d t Mon k jway i h a Pa Edgewater 428 7.30 7.40 8.07 471 8.15 9.15 487 8.15 9.00 428 9.10 9.35 9.50 vi r Cr R l D 1 College Rd Sy Fisher iv ey e t s r 428 8.00 8.10 8.40 471 8.45 9.45 487 9.15 10.00 428 10.10 10.35 10.50 e V N ia ek 428 8.30 8.40 9.10 497 9.15 10.05 487 10.15 11.00 428 11.10 11.35 11.50 ll B re Transferu s Rd at Otahuhu Pakuranga C 428 9.10 9.20 9.50 487 9.55 10.45 487 11.15 12.00 428 -

Importance of the Area

IMPORTANCE AREA FOR INVESTMENT OF THE AREA Whangarei The Upper North Island is responsible for over manufacturing economy, home to a number of half of the country’s entire freight movements, our most vibrant communities and the focus for with a large majority coming into, out of, or the East West Connections programme. through Auckland; making Auckland’s transport Increasing freight volumes and the anticipated network critical to New Zealand’s economic economic and population growth in the area will performance. place increasing pressure on both the nation’s At the heart of Auckland’s freight movements is supply chains and the local transport network. + SOUTHDOWN the area between Onehunga, East Tamaki and To ensure that the transport network can 130,000 6,000 FREIGHT employees heavy vehicle TERMINAL the Airport. This area is an industrial hub that continue to support this growing movement of (2nd largest area in movements per Key rail/road freight Auckland behind day along Church interchange employs over 130,000 people and generates people and goods, the NZ Transport Agency and the CBD) Street more than $10 billion a year in GDP. This area is Auckland Transport are working together on the engine room of New Zealand’s industrial and the East West Connections programme. Contributes $ % 10BILLION 16 per year GDP of Auckland’s GDP Onehunga East Tamaki Airport Glen Innes/ Glen Innes/ Stonefields Stonefields Howick Howick Sylvia Park Sylvia Park Pakuranga Penrose Pakuranga Penrose Onehunga Botany Botany Onehunga Mount Mount Wellington Wellington