Waitangi Tribunal Manukau Report (1985)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auckland District Plan

E E See Appendix 6 Diagram 12 !1!82A 307 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 182 ! ! !R I M ! ! U ! ! ! R ! ! O ! ! A ! D ! M O A ! ! N H ! U ! ! R ! ! N ! ! ! A ! ! ! ! G ! ! M ! ! ! A ! ! P ! ! ! ! D ! ! R 182 ! ! 2 I ! S V ! ! ! O E ! ! U ! O ! ! ! 6 T ! F ! H ! ! ! F ! - ! ! W ! ! ! R ! ! ! ! ! E A ! M ! ! S ! ! ! ! 12 T P ! ! ! E ! ! ! ! R ! ! 14A ! N ! ! ! ! Mangere Inlet M ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! O ! ! ! ! ! Ngarango Otainui ! ! T ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! O ! ! ! R ! ! ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A ! ! Island ! ! Y ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 182A ! ! ! ! D ! A ! ! RO ! ! ! ! U M IM ! ! ! ! R A ! ! H ! ! ! ! ! U ! ! ! ! ! N ! ! ! ! ! ! ! G ! ! 182A ! ! A ! ! ! ! ! ! D ! ! ! ! R ! ! ! ! I ! ! 22 V ! ! ! ! ! E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! S ! ! 26 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! o ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! u ! ! t ! h ! 21 ! 32 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! AD ! RO ! ! ! O 31 MIR ! ! ! ! ! ! 21 ! ! ! ! ! 5 ! ! ! ! ! 42 ! ! ! ! ! 307 ! ! ! ! ! 22 ! 42 ! ! ! ! ! ! 16 ! 12 ! ! ! ! 46 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 17C ! NUE ! VE ! ! A ! 17B A 31 ON ! M ! ! 16 ! ! 182 5 ! ! ! ! ! ! 5 17 ! ! ! ! ! ! 6 11 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 7 ! ! ! ! 17A 12 ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! " c ! ! !! ! e ! ! 280 !! s ! ! ! t 11 3A ! ! ! e ! 1 ! ! r ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! n ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 81 2 ! ! ! ! ! 77 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 71 56 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! " c ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! 62A ! ! ! 62 ! ! ! ! ! 5 ! ! ! ! 5 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 3 ! ! 66 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 51 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! E U ! ! ! ! N 11 VE ! ! E A ! I ! ! ! ST ! 41 ! ! HA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 72 ! ! ! ! ! ! 3 ! ! 56 ! -

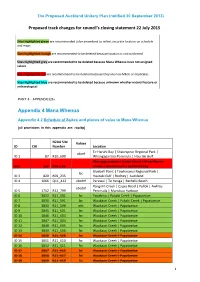

Appendix 4 Mana Whenua

The Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan (notified 30 September 2013) Proposed track changes for council’s closing statement 22 July 2015 Sites highlighted green are recommended to be amendend to reflect accurate location on schedule and maps Sites highlighted orange are recommended to be deleted because location is not confirmed Sites highlighted grey are recommended to be deleted because Mana Whenua have not assigned values Sites highlighted red are recommended to be deleted because they are non-Māori or duplicates Sites highlighted blue are recommended to be deleted because unknown whether natural feature or archaeological PART 5 • APPENDICES» Appendix 4 Mana Whenua Appendix 4.2 Schedule of Ssites and places of value to Mana Whenua [all provisions in this appendix are: rcp/dp] NZAA Site Values ID CHI Number Location Te Haruhi Bay | Shakespear Regional Park | abcef ID 1 87 R10_699 Whangaparaoa Peninsula | Hauraki Gulf. Whangaparapara | Aotea Island | Great Barrier ID 2 502 S09_116 Island. | Hauraki Gulf | Auckland City Bluebell Point | Tawharanui Regional Park | bc ID 3 829 R09_235 Hauraki Gulf | Rodney | Auckland ID 4 1066 Q11_412 abcdef Parawai | Te Henga | Bethells Beach Rangiriri Creek | Capes Road | Pollok | Awhitu abcdef ID 5 1752 R12_799 Peninsula | Manukau Harbour ID 6 3832 R11_581 bc Papahinu | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 7 3835 R11_591 bc Waokauri Creek | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 8 3843 R11_599 abc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 9 3845 R11_601 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 10 3846 R11_603 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe -

Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule

Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule [rcp/dp] Introduction The factors in B4.2.2(4) have been used to determine the features included in Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule, and will be used to assess proposed future additions to the schedule. ID Name Location Site type Description Unitary Plan criteria 2 Algies Beach Algies Bay E This site is one of the a, b, g melange best examples of an exposure of the contact between Northland Allocthon and Miocene Waitemata Group rocks. 3 Ambury Road Mangere F A complex 140m long a, b, c, lava cave Bridge lava cave with two d, g, i branches and many well- preserved flow features. Part of the cave contains unusual lava stalagmites with corresponding stalactites above. 4 Anawhata Waitākere A This locality includes a a, c, e, gorge and combination of g, i, l beach unmodified landforms, produced by the dynamic geomorphic processes of the Waitakere coast. Anawhata Beach is an exposed sandy beach, accumulated between dramatic rocky headlands. Inland from the beach, the Anawhata Stream has incised a deep gorge into the surrounding conglomerate rock. 5 Anawhata Waitākere E A well-exposed, and a, b, g, l intrusion unusual mushroom-shaped andesite intrusion in sea cliffs in a small embayment around rocks at the north side of Anawhata Beach. 6 Arataki Titirangi E The best and most easily a, c, l volcanic accessible exposure in breccia and the eastern Waitākere sandstone Ranges illustrating the interfingering nature of Auckland Unitary Plan Operative in part 1 Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule the coarse volcanic breccias from the Waitākere Volcano with the volcanic-poor Waitematā Basin sandstone and siltstones. -

Regional Assessment of Areas Susceptible to Coastal Erosion Volume 2: Appendices a - J February TR 2009/009

Regional Assessment of Areas Susceptible to Coastal Erosion Volume 2: Appendices A - J February TR 2009/009 Auckland Regional Council Technical Report No. 009 February 2009 ISSN 1179-0504 (Print) ISSN 1179-0512 (Online) ISBN 978-1-877528-16-3 Contents Appendix A: Consultants Brief Appendix B: Peer reviewer’s comments Appendix C: Summary of Relevant Tonkin & Taylor Jobs Appendix D: Summary of Shoreline Characterization Appendix E: Field Investigation Data Appendix F: Summary of Regional Beach Properties Appendix G: Summary of Regional Cliff Properties Appendix H: Description of Physical Setting Appendix I: Heli-Survey DVDs (Contact ARC Librarian) Appendix J: Analysis of Beach Profile Changes Regional Assessment of Areas Susceptible to Coastal Erosion, Volume 2: Appendices A-J Appendix A: Consultants Brief Appendix B: Peer reviewer’s comments Appendix C: Summary of relevant Tonkin & Taylor jobs Job Number North East Year of Weathered Depth is Weathered Typical Cliff Cliff Slope Cliff Slope Composite Composite Final Slope Geology Rec Setback erosion rate Comments Street address Suburb investigation layer depth Estimated/ layer Slope weathered layer Height (deg) (rads) slope from slope from (degree) from Crest (m) (m/yr) (m) Greater than (deg) slope (rad) (m) calc (degree) profile (deg) 6 RIVERVIEW PANMURE 12531.000 2676066 6475685 1994 2.40 58 0.454 12.0 51.5 0.899 43.70 35 35 avt 6 ROAD 15590.000 6472865 2675315 2001 2.40 0.454 4.0 30.0 0.524 27.48 27 avt 8 29 MATAROA RD OTAHUHU 16619.000 6475823 2675659 1999 2.40 0.454 6.0 50.0 0.873 37.07 37 avt LAGOON DRIVE PANMURE long term recession ~ FIDELIS AVENUE 5890.000 2665773 6529758 1983 0.75 G 0.454 0.000 N.D Kk 15 - 20 0.050 50mm/yr 80m setback from toe FIDELIS AVE ALGIES BAY recc. -

Southeastern Manukau / Pahurehure Inlet Contaminant Study: Hydrodynamic, Wave and Sediment-Transport Model Implementation and Calibration December TR 2008/056

Southeastern Manukau / Pahurehure Inlet Contaminant Study: Hydrodynamic, Wave and Sediment-Transport Model Implementation and Calibration December TR 2008/056 Auckland Regional Council Technical Report No.056 December 2008 ISSN 1179-0504 (Print) ISSN 1179-0512 (Online) ISBN 978-1-877528-04-0 Technical Report. First Edition. Reviewed by: Approved for ARC Publication by: Name: Judy-Ann Ansen Name: Matthew Davis Position: Acting Team Leader Position: Group Manager Stormwater Action Team Partnerships & Community Programmes Organisation: Auckland Regional Council Organisation: Auckland Regional Council Date: 28 October 2010 Date: 28 October 2010 Recommended Citation: Pritchard, M; Gorman, R; Lewis, M. (2008). Southeastern Manukau Harbour / Pahurehure Inlet Contaminant Study. Hydrodynamic Wave and Sediment Transport Model Implementation and Calibration. Prepared by NIWA for Auckland Regional Council. Auckland Regional Council Technical Report 2008/056. © 2008 Auckland Regional Council This publication is provided strictly subject to Auckland Regional Council's (ARC) copyright and other intellectual property rights (if any) in the publication. Users of the publication may only access, reproduce and use the publication, in a secure digital medium or hard copy, for responsible genuine non-commercial purposes relating to personal, public service or educational purposes, provided that the publication is only ever accurately reproduced and proper attribution of its source, publication date and authorship is attached to any use or reproduction. This -

Pukekawa — the Domain Volcano

Pukekawa — the Domain Volcano New Zealand is a land of volcanoes The springs provided Auckland’s first leading the Ngapuhi from the North and earthquakes. Volcanic activity has piped water supply in 1866. The and Potatau Te Wherowhero leading played a major role in shaping New Domain Wintergarden’s fernery occu- the local Ngati Whatua. A sacred Zealand since its earliest origins, pies a disused scoria quarry on the Totara tree planted by Princess Te around 500 million years ago. north side of the small central scoria Puea Herangi to commemorate the Auckland City is built on an active field cone. battles and the eventual settlement of of small basalt volcanoes. Forty-eight the dispute stands on Pukekaroa sur- have erupted within 29km of the city Maori Use of Pukekawa rounded by a palisade. centre over the last 150 000 years. The The Domain has been altered signifi- Later Use of Auckland’s most recent eruption, 600 years ago, cantly by contact with humans. When Volcanoes formed Rangitoto Island at the en- Maori people arrived in Auckland they trance to Auckland Harbour. Because cleared the land for gardens, particu- Pukekawa was part of the land which of the intensity of past volcanic and larly choosing the fertile north-facing Ngati Whatua sold to the Europeans geologic activity within the Auckland who by 1860 had drained and filled region another eruption possible. slopes of the volcanic cones. Later their descendants looked to more per- the swamp and turned it into cricket Auckland Domain Volcano manent settlements, so that parts of fields. -

Immigration During the Crown Colony Period, 1840-1852

1 2: Immigration during the Crown Colony period, 1840-1852 Context In 1840 New Zealand became, formally, a part of the British Empire. The small and irregular inflow of British immigrants from the Australian Colonies – the ‘Old New Zealanders’ of the mission stations, whaling stations, timber depots, trader settlements, and small pastoral and agricultural outposts, mostly scattered along the coasts - abruptly gave way to the first of a number of waves of immigrants which flowed in from 1840.1 At least three streams arrived during the period 1840-1852, although ‘Old New Zealanders’ continued to arrive in small numbers during the 1840s. The first consisted of the government officials, merchants, pastoralists, and other independent arrivals, the second of the ‘colonists’ (or land purchasers) and the ‘emigrants’ (or assisted arrivals) of the New Zealand Company and its affiliates, and the third of the imperial soldiers (and some sailors) who began arriving in 1845. New Zealand’s European population grew rapidly, marked by the establishment of urban communities, the colonial capital of Auckland (1840), and the Company settlements of Wellington (1840), Petre (Wanganui, 1840), New Plymouth (1841), Nelson (1842), Otago (1848), and Canterbury (1850). Into Auckland flowed most of the independent and military streams, and into the company settlements those arriving directly from the United Kingdom. Thus A.S.Thomson observed that ‘The northern [Auckland] settlers were chiefly derived from Australia; those in the south from Great Britain. The former,’ he added, ‘were distinguished for colonial wisdom; the latter for education and good home connections …’2 Annexation occurred at a time when emigration from the United Kingdom was rising. -

Auckland Trail Notes Contents

22 October 2020 Auckland trail notes Contents • Mangawhai to Pakiri • Mt Tamahunga (Te Hikoi O Te Kiri) Track • Govan Wilson to Puhoi Valley • Puhoi Track • Puhoi to Wenderholm by kayak • Puhoi to Wenderholm by walk • Wenderholm to Stillwater • Okura to Long Bay • North Shore Coastal Walk • Coast to Coast Walkway • Onehunga to Puhinui • Puhinui Stream Track • Totara Park to Mangatawhiri River • Hunua Ranges • Mangatawhiri to Mercer Mangawhai to Pakiri Route From Mangawhai Heads carpark, follow the road to the walkway by 44 Wintle Street which leads down to the estuary. Follow the estuary past a camping ground, a boat ramp & holiday baches until wooden steps lead up to the Findlay Street walkway. From Findlay Street, head left into Molesworth Drive until reaching Mangawhai Village. Then a right into Moir Street, left into Insley Street and across the estuary then left into Black Swamp Road. Follow this road until reaching Pacific Road which leads you through a forestry block to the beach and the next stage of Te Araroa. Bypass Note: You could obtain a boat ride across the estuary to the Mangawhai Spit to avoid the road walking section. Care of sand-nesting birds is required on this Scientific Wildlife Reserve - please stick to the shoreline. Just 1km south, a stream cuts across the beach and it can go over thigh height, as can other water crossings on this track. Follow the coast southwards for another 2km, then take the 1 track over Te Ārai Point. Once back on the beach, continue south for 12km (fording Poutawa Stream on the way) until you cross the Pākiri River then head inland to reach the end of Pākiri River Road. -

Auckland Plan Targets: Monitoring Report 2015 with DATA for the SOUTHERN INITIATIVE AREA

Auckland plan targets: monitoring report 2015 WITH DATA FOR THE SOUTHERN INITIATIVE AREA Auckland Plan Targets: Monitoring Report 2015 With Data for the Southern Initiative Area March 2016 Technical Report 2016/007 Auckland Council Technical Report 2016/007 ISSN 2230-4525 (Print) ISSN 2230-4533 (Online) ISBN 978-0-9941350-0-1 (Print) ISBN 978-0-9941350-1-8 (PDF) This report has been peer reviewed by the Peer Review Panel. Submitted for review on 26 February 2016 Review completed on 18 March 2016 Reviewed by one reviewer. Approved for Auckland Council publication by: Name: Dr Lucy Baragwanath Position: Manager, Research and Evaluation Unit Date: 18 March 2016 Recommended citation Wilson, R., Reid, A and Bishop, C (2016). Auckland Plan targets: monitoring report 2015 with data for the Southern Initiative area. Auckland Council technical report, TR2016/007 Note This technical report updates and replaces Auckland Council technical report TR2015/030 Auckland Plan Targets: monitoring report 2015 which does not contain data for the Southern Initiative area. © 2016 Auckland Council This publication is provided strictly subject to Auckland Council's copyright and other intellectual property rights (if any) in the publication. Users of the publication may only access, reproduce and use the publication, in a secure digital medium or hard copy, for responsible genuine non-commercial purposes relating to personal, public service or educational purposes, provided that the publication is only ever accurately reproduced and proper attribution of its source, publication date and authorship is attached to any use or reproduction. This publication must not be used in any way for any commercial purpose without the prior written consent of Auckland Council. -

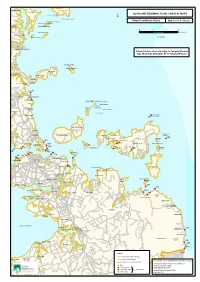

Coastal Map Series 3

HEPBURN CREEK KAWAU ISLAND ALGIES BAY BEEHIVE ISLAND CHALLENGER ISLAND MOTUKETEKETE ISLAND MOTUREKAREKA ISLAND PUKAPUKA MOTUTARA ISLAND MOTUORA ISLAND MAHURANGI WEST 1 TE HAUPA ISLAND WENDERHOLM WAIWERA MAHURANGI IS OREWA WOODED ISLAND TIRITIRI MATANGI ISLAND REGIONAL PARK SILVERDALE MATAKATIA BAY BIG MANLY ARKLES BAY STILLWATER WADE HEADS 21 LONG BAY OKURA MARINE RESERVE LONG BAY REGIONAL PARK MOTUHOROPAPA ISLAND THE NOISES TORBAY DAVID ROCKS OTATA ISLAND RAKINO IS. ZENO ROCK BROWNS BAY MARIA ISLAND ALBANY THE NOISES HORUHORU ROCK MURRAYS BAY 173(Gannet Rock) MAIRANGI BAY MOTUTAPU ISLAND MILFORD TARAHIKI IS TAKAPUNA RANGITOTO ISLAND ONEROA PALM BEACH (Shag Is) BEACH HAVEN BLACKPOOL 115 SURFDALE ONETANGI PAKATOA ISLAND 167 OSTENDWAIHEKE ISLAND 94 WAIHEKE ISLAND NORTHCOTE 168 FRENCHMANS CAP DOMAIN BAYSWATER MOTUIHE IS. 169 42 PAPAKOHATU IS 89OMIHA ROTOROA (Crusoe Is) 106 ISLAND 41 DEVONPORTHEAD 170 46 64 BROWNS IS. 172 (Motukorea) 44 HERNE BAY 66 KOHIMARAMA 172 ST HELIERS AUCKLAND ORAKEI PT. CHEVALIER DOMAIN GLENDOWIE TAHUNA BEACH WATERVIEW GLEN INNES PONUI ISLAND REMUERA 74 MOTUKARAKA IS (Chamberlins Is) PARKMARAETAI BEACHLANDS FARM COVE PANMURE HOWICK PANMURE BASIN BEACHLANDS PAKIHI ISLAND MT WELLINGTON DUDER PARK 126 PAKURANGA ONEHUNGA BLOCKHOUSE BAY 130 176 NIMT AMBURY REGIONAL PARK 174 OTAHUHU EAST TAMAKI WHITFORD 175 REGIONAL MANGERE SEWAGE PARK KAWAKAWA BAY PUKETUTU ISLAND MANGERE ORERE POINT ORERE TAPAPAKANGA REGIONAL PARK CLEVEDON PUHINUI MATINGARAHI WIROA IS. MANUREWA MANUKAU HARBOUR WEYMOUTH TAKANINI WAHARAU 177 WATTLE DOWNSCONIFER GROVE REGIONAL PARK PAPAKURA WHAREKAWA HUNUA RANGES REGIONAL PARK 178 ELLETS BEACH SEAGROVE 179 KARAKA 180 DRURY KAIAUA KINGSEAT CLARKS BEACH WAIAU PA GLENBROOK BEACH. -

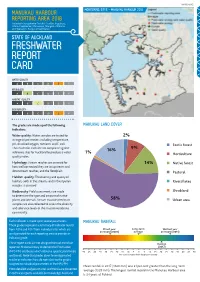

Freshwater Report Card

19-PRO-0142 MANUKAU HARBOUR MONITORING SITES – MANUKAU HARBOUR 2018 REPORTING AREA 2018 Includes Maungakiekie-Tamaki, Franklin, Papakura, Ōtara-Papatoetoe, Manurewa, Mangere-Otahuhu and Waitakere Ranges Local Boards STATE OF AUCKLAND FRESHWATER REPORT CARD WATER QUALITY A B C D E F HYDROLOGY A B C D E F HABITAT QUALITY A B C D E F BIODIVERSITY A B C D E F The grades are made up of the following MANUKAU LAND COVER indicators: Water quality: Water samples are tested for 2% a range of parameters including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrients and E. coli. Exotic forest The results for each site are compared against 16% 9% reference sites for Auckland to produce a water 1% Horticulture quality index. Hydrology: Stream reaches are assessed for 14% Native forest how well connected they are to upstream and downstream reaches, and the floodplain. Pastoral Habitat quality: The diversity and quality of habitats both in the streams and in the riparian Rivers/lakes margins is assessed. Biodiversity: Field assessments are made Shrubland to determine the type and amount of native plants and animals. Stream macroinvertebrate 58% Urban area samples are also collected to assess the diversity and tolerance levels of the macroinvertebrate community. Each indicator is made up of several parameters. MANUKAU RAINFALL These grades represent a summary of indicator results from 2016 and 2017 from individual sites which are Driest year Wettest year on record (2002) on record (2011) amalgamated for each reporting area to provide an indicator grade. These report cards are not designed to track trends or Rainfall report on National Policy Statement for Freshwater (2017) (NPS-FM) attributes which relate to specific parameters and bands. -

![In the High Court of New Zealand Auckland Registry I Te Kōti Matua O Aotearoa Tāmaki Makaurau Rohe Civ-2013-404-5224 [2018] Nz](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5980/in-the-high-court-of-new-zealand-auckland-registry-i-te-k%C5%8Dti-matua-o-aotearoa-t%C4%81maki-makaurau-rohe-civ-2013-404-5224-2018-nz-985980.webp)

In the High Court of New Zealand Auckland Registry I Te Kōti Matua O Aotearoa Tāmaki Makaurau Rohe Civ-2013-404-5224 [2018] Nz

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND AUCKLAND REGISTRY I TE KŌTI MATUA O AOTEAROA TĀMAKI MAKAURAU ROHE CIV-2013-404-5224 [2018] NZHC 2550 BETWEEN TE ARA RANGATU O TE IWI O NGATI TE ATA WAIOHUA INCORPORATED First Plaintiff AND RIKI MINHINNICK Second Plaintiff AND THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW ZEALAND for/on behalf of the CROWN First Defendant CONTINUED OVERLEAF Hearing: 21 – 22 May 2018 Appearances: No appearance by or on behalf of the plaintiffs S Kinsler and S Tandon for First Defendant J Hodder QC, T Smith and A Wicks for Second and Third Defendants/Counterclaim Plaintiffs H Wilson and J Taylor for Counterclaim Defendant Judgment: 28 September 2018 JUDGMENT OF POWELL J This judgment was delivered by me on 28 September 2018 at 4.30 pm pursuant to R 11.5 of the High Court Rules Registrar/Deputy Registrar Date: TE ARA RANGATU O TE IWI O NGATI TE ATA WAIOHUA INCORPORATED & ORS v THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW ZEALAND for/on behalf of the CROWN & ORS [2018] NZHC 2550 [28 September 2018] AND NEW ZEALAND STEEL LIMITED Second Defendant AND WAIKATO NORTH HEAD MINING LIMITED Third Defendant AND HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND POUHERE TAONGA Counterclaim Defendant [1] The counterclaim plaintiffs, New Zealand Steel Ltd and Waikato North Head Mining Ltd (“New Zealand Steel”), mine ironsands on land known as Maioro, located on the North Head of the Waikato River. The ironsands are mined pursuant to a Deed of Licence from the Crown dated 3 June 1966 (“the Licence”), with mining operations ongoing since 1968.1 [2] The Licence was issued under the Iron and Steel Industry