DNA Barcodes for Bio-Surveillance: Regulated and Economically Important Arthropod Plant Pests1 Muhammad Ashfaq and Paul D.N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DNA Barcodes for Bio-Surveillance

Page 1 of 44 DNA Barcodes for Bio-surveillance: Regulated and Economically Important Arthropod Plant Pests Muhammad Ashfaq* and Paul D.N. Hebert Centre for Biodiversity Genomics, Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada * Corresponding author: Muhammad Ashfaq Centre for Biodiversity Genomics, Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON N1G 2W1, Canada Email: [email protected] Phone: (519) 824-4120 Ext. 56393 Genome Downloaded from www.nrcresearchpress.com by 99.245.208.197 on 09/06/16 1 For personal use only. This Just-IN manuscript is the accepted prior to copy editing and page composition. It may differ from final official version of record. Page 2 of 44 Abstract Many of the arthropod species that are important pests of agriculture and forestry are impossible to discriminate morphologically throughout all of their life stages. Some cannot be differentiated at any life stage. Over the past decade, DNA barcoding has gained increasing adoption as a tool to both identify known species and to reveal cryptic taxa. Although there has not been a focused effort to develop a barcode library for them, reference sequences are now available for 77% of the 409 species of arthropods documented on major pest databases. Aside from developing the reference library needed to guide specimen identifications, past barcode studies have revealed that a significant fraction of arthropod pests are a complex of allied taxa. Because of their importance as pests and disease vectors impacting global agriculture and forestry, DNA barcode results on these arthropods have significant implications for quarantine detection, regulation, and management. -

Alien Invasive Species and International Trade

Forest Research Institute Alien Invasive Species and International Trade Edited by Hugh Evans and Tomasz Oszako Warsaw 2007 Reviewers: Steve Woodward (University of Aberdeen, School of Biological Sciences, Scotland, UK) François Lefort (University of Applied Science in Lullier, Switzerland) © Copyright by Forest Research Institute, Warsaw 2007 ISBN 978-83-87647-64-3 Description of photographs on the covers: Alder decline in Poland – T. Oszako, Forest Research Institute, Poland ALB Brighton – Forest Research, UK; Anoplophora exit hole (example of wood packaging pathway) – R. Burgess, Forestry Commission, UK Cameraria adult Brussels – P. Roose, Belgium; Cameraria damage medium view – Forest Research, UK; other photographs description inside articles – see Belbahri et al. Language Editor: James Richards Layout: Gra¿yna Szujecka Print: Sowa–Print on Demand www.sowadruk.pl, phone: +48 022 431 81 40 Instytut Badawczy Leœnictwa 05-090 Raszyn, ul. Braci Leœnej 3, phone [+48 22] 715 06 16 e-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction .......................................6 Part I – EXTENDED ABSTRACTS Thomas Jung, Marla Downing, Markus Blaschke, Thomas Vernon Phytophthora root and collar rot of alders caused by the invasive Phytophthora alni: actual distribution, pathways, and modeled potential distribution in Bavaria ......................10 Tomasz Oszako, Leszek B. Orlikowski, Aleksandra Trzewik, Teresa Orlikowska Studies on the occurrence of Phytophthora ramorum in nurseries, forest stands and garden centers ..........................19 Lassaad Belbahri, Eduardo Moralejo, Gautier Calmin, François Lefort, Jose A. Garcia, Enrique Descals Reports of Phytophthora hedraiandra on Viburnum tinus and Rhododendron catawbiense in Spain ..................26 Leszek B. Orlikowski, Tomasz Oszako The influence of nursery-cultivated plants, as well as cereals, legumes and crucifers, on selected species of Phytophthopra ............30 Lassaad Belbahri, Gautier Calmin, Tomasz Oszako, Eduardo Moralejo, Jose A. -

A Faunal Survey of the Elateroidea of Montana by Catherine Elaine

A faunal survey of the elateroidea of Montana by Catherine Elaine Seibert A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology Montana State University © Copyright by Catherine Elaine Seibert (1993) Abstract: The beetle family Elateridae is a large and taxonomically difficult group of insects that includes many economically important species of cultivated crops. Elaterid larvae, or wireworms, have a history of damaging small grains in Montana. Although chemical seed treatments have controlled wireworm damage since the early 1950's, it is- highly probable that their availability will become limited, if not completely unavailable, in the near future. In that event, information about Montana's elaterid fauna, particularity which species are present and where, will be necessary for renewed research efforts directed at wireworm management. A faunal survey of the superfamily Elateroidea, including the Elateridae and three closely related families, was undertaken to determine the species composition and distribution in Montana. Because elateroid larvae are difficult to collect and identify, the survey concentrated exclusively on adult beetles. This effort involved both the collection of Montana elateroids from the field and extensive borrowing of the same from museum sources. Results from the survey identified one artematopid, 152 elaterid, six throscid, and seven eucnemid species from Montana. County distributions for each species were mapped. In addition, dichotomous keys, and taxonomic and biological information, were compiled for various taxa. Species of potential economic importance were also noted, along with their host plants. Although the knowledge of the superfamily' has been improved significantly, it is not complete. -

Conogethes Punctiferalis

Conogethes punctiferalis Scientific Name Conogethes punctiferalis (Guenée, 1854) (Astura) Synonyms: Astura punctiferalis Guenée, 1854 Botys nicippealis Walker, 1859 Deiopeia detracta Walker, 1859 Astura guttatalis Walker, 1866 Taxonomic Note: Conogethes and Dichocrocis have been considered synonyms in the older literature; and punctiferalis is often seen combined with Dichocrocis (Wang, 1980). Conogethes punctiferalis has been a species complex (Solis, 1999) and difficult to identify at the species level. There has been no taxonomic revision of Conogethes to separate species or range within the genus (Robinson et al., 1994). Inoue and Yamanaka (2006) re- described C. punctiferalis and described two new closely allied species that have been confused with C. punctiferalis in the literature. This study illustrates and clearly describes the external morphology and genitalic Figures 1 & 2. Conogethes punctiferalis adult, dorsal and ventral views (Pest and Diseases Image Library, differentiation of C. punctiferalis Bugwood.org). based on studies of the type specimens. They state that the synonyms above should be “critically reconsidered” and do not include them in their synonymy. Species in this complex have very similar morphology, variable color morphs, and overlapping host ranges (Armstrong, 2010). Because the identities of species in the literature is unknown and their biology is indistinguishable, this datasheet has been written using information on all species within the C. punctiferalis species complex, with emphasis placed on the polyphagous -

A Baseline Invertebrate Survey of the Knepp Estate - 2015

A baseline invertebrate survey of the Knepp Estate - 2015 Graeme Lyons May 2016 1 Contents Page Summary...................................................................................... 3 Introduction.................................................................................. 5 Methodologies............................................................................... 15 Results....................................................................................... 17 Conclusions................................................................................... 44 Management recommendations........................................................... 51 References & bibliography................................................................. 53 Acknowledgements.......................................................................... 55 Appendices.................................................................................... 55 Front cover: One of the southern fields showing dominance by Common Fleabane. 2 0 – Summary The Knepp Wildlands Project is a large rewilding project where natural processes predominate. Large grazing herbivores drive the ecology of the site and can have a profound impact on invertebrates, both positive and negative. This survey was commissioned in order to assess the site’s invertebrate assemblage in a standardised and repeatable way both internally between fields and sections and temporally between years. Eight fields were selected across the estate with two in the north, two in the central block -

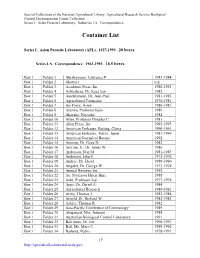

Container List

Special Collections of the National Agricultural Library: Agricultural Research Service Biological Control Documentation Center Collection Series I. Asian Parasite Laboratory. Subseries I.A. Correspondence. Container List Series I. Asian Parasite Laboratory (APL). 1927-1993. 20 boxes. Series I.A. Correspondence. 1963-1993. 16.5 boxes. Box 1 Folder 1 Abrahamson, Lawrence P. 1983-1984 Box 1 Folder 2 Abstract n.d. Box 1 Folder 3 Academic Press, Inc. 1986-1993 Box 1 Folder 4 Achterberg, Dr. Kees van 1982 Box 1 Folder 5 Aeschlimann, Dr. Jean-Paul 1981-1985 Box 1 Folder 6 Agricultural Counselor 1976-1981 Box 1 Folder 7 Air Force, Army 1980-1981 Box 1 Folder 8 Aizawa, Professor Keio 1986 Box 1 Folder 9 Akasaka, Naoyuki 1982 Box 1 Folder 10 Allen, Professor Douglas C. 1981 Box 1 Folder 11 Allen Press, Inc. 1992-1993 Box 1 Folder 12 American Embassy, Beijing, China 1990-1991 Box 1 Folder 13 American Embassy, Tokyo, Japan 1981-1990 Box 1 Folder 14 American Journal of Botany 1992 Box 1 Folder 15 Amman, Dr. Gene D. 1982 Box 1 Folder 16 Amrine, Jr., Dr. James W. 1986 Box 1 Folder 17 Anderson, Don M. 1981-1983 Box 1 Folder 18 Anderson, John F. 1975-1976 Box 1 Folder 19 Andres, Dr. Lloyd 1989-1990 Box 1 Folder 20 Angalet, Dr. George W. 1973-1978 Box 1 Folder 21 Annual Reviews Inc. 1992 Box 1 Folder 22 Ao, Professor Hsien-Bine 1988 Box 1 Folder 23 Aoki, Professor Joji 1977-1978 Box 1 Folder 24 Apps, Dr. Darrel A. 1984 Box 1 Folder 25 Agricultural Research 1980-1981 Box 1 Folder 26 Army, Thomas J. -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying -

Integrating Cultural Tactics Into the Management of Bark Beetle and Reforestation Pests1

DA United States US Department of Proceedings --z:;;-;;; Agriculture Forest Service Integrating Cultural Tactics into Northeastern Forest Experiment Station the Management of Bark Beetle General Technical Report NE-236 and Reforestation Pests Edited by: Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team J.C. Gregoire A.M. Liebhold F.M. Stephen K.R. Day S.M.Salom Vallombrosa, Italy September 1-3, 1996 Most of the papers in this publication were submitted electronically and were edited to achieve a uniform format and type face. Each contributor is responsible for the accuracy and content of his or her own paper. Statements of the contributors from outside the U.S. Department of Agriculture may not necessarily reflect the policy of the Department. Some participants did not submit papers so they have not been included. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the Forest Service of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. Remarks about pesticides appear in some technical papers contained in these proceedings. Publication of these statements does not constitute endorsement or recommendation of them by the conference sponsors, nor does it imply that uses discussed have been registered. Use of most pesticides is regulated by State and Federal Law. Applicable regulations must be obtained from the appropriate regulatory agencies. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish and other wildlife - if they are not handled and applied properly. -

The Bark and Ambrosia Beetle (Coleoptera, Scolytinae) Collection at the University Museum of Bergen – with Notes on Extended Distributions in Norway

© Norwegian Journal of Entomology. 1 July 2019 The bark and ambrosia beetle (Coleoptera, Scolytinae) collection at the University Museum of Bergen – with notes on extended distributions in Norway BJARTE H. JORDAL Jordal, B.H. 2019. The bark and ambrosia beetle (Coleoptera, Scolytinae) collection at the University Museum of Bergen – with notes on extended distributions in Norway. Norwegian Journal of Entomology 66, 19–31. The bark and ambrosia beetle collection at the University Museum in Bergen has been curated and digitized, and is available in public databases. Several species were recorded from Western Norway for the first or second time. The pine inhabiting species Hylastes opacus Erichson, 1836 is reported from Western Norway for the first time, and the rare speciesPityogenes trepanatus (Nordlinger, 1848) for the second time. The spruce inhabiting species Pityogenes chalcographus (Linnaeus, 1761) and Cryphalus asperatus (Gyllenhal, 1813), which are common in eastern Norway, were recorded in several Western Norway localities. Broadleaf inhabiting species such as Anisandrus dispar (Fabricius, 1792), Taphrorychus bicolor (Herbst, 1793), Dryocoetes villosus (Fabricius, 1792), Scolytus laevis Chapuis, 1869 and Scolytus ratzeburgi Janson, 1856 were collected for the second or third time in Western Norway. Several common species – likely neglected in previous sampling efforts – are well established in Western and Northern Norway. Key words: Curculionidae, Scolytinae, Norway spruce, Western Norway, geographical distribution. Bjarte H. Jordal, University Museum of Bergen – The Natural History Museum, University of Bergen, PB7800, NO-5020 Bergen. E-mail: [email protected] Introduction A large proportion of bark and ambrosia beetles in Norway are breeding in conifer host plants. Bark and ambrosia beetles are snoutless weevils Among the 72 species currently known from in the subfamily Scolytinae. -

Japanese Pyraustinæ (Lepid.)

Title ON THE KNOWN AND UNRECORDED SPECIES OF THE JAPANESE PYRAUSTINÆ (LEPID.) Author(s) SHIBUYA, Jinshichi Citation Journal of the Faculty of Agriculture, Hokkaido Imperial University, 25(3), 151-242 Issue Date 1929-06-15 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/12650 Type bulletin (article) File Information 25(3)_p151-242.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP ON THE KNOWN AND UNRECORDED SPECIES OF THE JAPANESE PYRAUSTINJE (LEPID.) BY JINSHICHI SHIBU¥A~ The object of this paper is to give a systematic account of the species belonging to the pyraustinae, a subfamily of ryralidae, Lepidoptera, which have hitherto been described from Japan, or recorded as occurring in this country. The preliminary account of the Pyraustinae of Japan was given by C. STOLL in his Papillons Exotiques, vol. iv, 1782, and in this publication he described a new species Phalaena (Pyralis) fascialis STOLL (=l£ymenia recurvalis FABR.). In 1860, MOTSCHULSKY in Etud. Entom. vol. ix, enu merated a new genus Nomis (= Udea), two new species Sylepta quadri maculalis, Udea albopedalis, the latter is the genotype of Nomis, and an unrecorded species Pyrausta sambucalis SCHIFF. et DEN. In regard to Sylepta quadrimaculalis MOTSCH., this species was originally placed under genus Botyodes, and with its specific name Sylepta quadrimaculalis was already given by KOLLER for a Pyralid-moth in 1844, while G. F. HAMPSON elected a new name Sylepta inferior H~IPSN. for S. quadrimaculalis MOTSCH. In 1863, LEDERER in Wien. Ent. Mon. vii, recorded Margaronia perspectalz's 1 \VLK. from this country as Phace!lura advenalz's LED. -

Naturally-Occurring Entomopathogenic Fungi on Three Bark Beetle Species (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Bulgaria

Pestic. Phytomed. (Belgrade), 25(1), 2010, 59-63 UDC: 630*1:632.7:632.937.1:582.288(497.2) Pestic. fitomed. (Beograd), 25(1), 2010, 59-63 Scientific paper * Naučni rad DOI: 10.2298/PIF1001059D Naturally-Occurring Entomopathogenic Fungi on Three Bark Beetle Species (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Bulgaria Slavimira A. Draganova1, Danail I. Takov2 and Danail D. Doychev3 1Plant Protection Institute, 35 Panajot Volov Str., 2230 Kostinbrod, Bulgaria ([email protected]) 2Institute of Zoology, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 1 Tsar Osvoboditel Boulevard, 1000 Sofia, Bulgaria 3University of Forestry, 10 St. Kliment Ohridski Boulevard, 1756 Sofia, Bulgaria Received: December 3, 2009 Accepted: February 2, 2010 SUMMARY Bark beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) belong to one of the most damag- ing groups of forest insects and the activity of their natural enemies – pathogens, parasi- toids, parasites or predators suppressing their population density, is of great importance. Biodiversity of entomopathogenic fungi on bark beetles in Bulgaria has been investi- gated sporadically. The aim of this preliminary study was to find, identify and study mor- phological characteristics of fungal entomopathogens naturally-occurring in populations of three curculionid species – Ips sexdentatus Boern, Ips typographus (L.) and Dryocoetes autographus (Ratz.). Dead pest adults were found under the bark of Pinus sylvestris and Picea abies trees col- lected from forests in the Maleshevska and Vitosha Mountains. Fungal pathogens were isolated into pure cultures on SDAY (Sabouraud dextrose agar with yeast extract) and were identified based on morphological characteristics both on the host and in a culture. Morphological characteristics of the isolates were studied by phenotypic methods. The fungal isolates obtained from dead adults of Ips sexdentatus, Ips typographus and D. -

Biological-Control-Programmes-In

Biological Control Programmes in Canada 2001–2012 This page intentionally left blank Biological Control Programmes in Canada 2001–2012 Edited by P.G. Mason1 and D.R. Gillespie2 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 2Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Agassiz, British Columbia, Canada iii CABI is a trading name of CAB International CABI Head Offi ce CABI Nosworthy Way 38 Chauncey Street Wallingford Suite 1002 Oxfordshire OX10 8DE Boston, MA 02111 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 T: +1 800 552 3083 (toll free) Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 T: +1 (0)617 395 4051 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cabi.org Chapters 1–4, 6–11, 15–17, 19, 21, 23, 25–28, 30–32, 34–36, 39–42, 44, 46–48, 52–56, 60–61, 64–71 © Crown Copyright 2013. Reproduced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery. Remaining chapters © CAB International 2013. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electroni- cally, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library, London, UK. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Biological control programmes in Canada, 2001-2012 / [edited by] P.G. Mason and D.R. Gillespie. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-78064-257-4 (alk. paper) 1. Insect pests--Biological control--Canada. 2. Weeds--Biological con- trol--Canada. 3. Phytopathogenic microorganisms--Biological control- -Canada.