The Paradox of Pride and Loathing, and Other Problems Author(S): Simon J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seafood Soup & Salad Meats Vegetables Extras

SOUP & SALAD SEAFOOD MEATS Miso Tuna Salad Turtle Soup Certified Japanese Wagyu miso marinated tuna, spicy tuna carpaccio, topped with sherry 9 / 18 ruby red grapefruit ponzu and crispy shallots spinach and wakame salad, dashi vinaigrette, 14 per oz (3 oz minimum) Fried Chicken & Andouille Gumbo sesame chip 14 a la Chef Paul 9 Fried Smoked Oysters Grilled Sweetbreads bourbon tomato jam, white remoulade 14 charred polenta cake, sherry braised cipollini Pickled Shrimp Salad onion, chimmichurri, sauce soubise 15 lolla rosa, Creole mustard vinaigrette, Crabmeat Spaetzle Italian cherry peppers, Provolone, prosciutto, Creole mustard dumplings, jumbo lump crab, Beef Barbacoa Sopes roasted corn, green tomato chow chow 10 / 20 green garbanzos, brown butter 12 crispy masa shell, red chili braised beef, queso fresco, pickled vegetables, avocado crema 11 City Park Salad Brown Butter Glazed Flounder & Crab baby red oak, romaine, granny smith apples, almond butter, green beans, lemon gelée, Golden City Lamb Ribs Stilton blue, applewood smoked bacon 8 / 16 almond wafer 16 Mississippi sorghum & soy glaze, fermented bean paste, charred cabbage, BBQ Shrimp Agnolotti Cheese Plate fried peanuts 13 / 26 chef’s selection of cheeses, quince paste, white stuffed pasta, BBQ and cream cheese filling, truffle honey, hazelnuts & water crackers 15 lemon crème fraîche, Gulf shrimp 13 / 26 Vadouvan Shrimp & Grits Rabbit Sauce Piquante vadouvan, garam masala, broken rice grits, slow braised leg, tasso jambalaya stuffing, VEGETABLES housemade chili sauce, fresh yogurt -

The Good Food Doctor: Heeats•Hesh Ots•Heposts

20 Interview By Dr Hsu Li Yang, Editorial Board Member The Good Food Doctor: heeats•hesh ots•heposts... Hsu Li Yang (HLY): Leslie, thank you very much for agreeing to participate in this interview with the SMA News. What made you start this “ieatishootipost” food blog? Dr Leslie Tay (LT): I had been overseas for a long time and when I finally came back to Singapore, I began to appreciate just how much of a Singaporean I really am. You know, my perfect breakfast would be two roti prata with a cup of teh tarik or kopi and kaya toast. Sometimes I feel we take our very own Singapore food for granted, that is, until we live overseas. About two years ago, I suddenly felt that even is day job is that of a family doctor though I love Singapore food, I don’t really know (one of two founding partners where all the good stuff is – where’s the best hokkien mee, the best chicken rice and so on. So I decided, of Karri Family Clinic) in the H okay, let’s go and try all these food as a hobby. When Tampines heartlands. But Dr Leslie Tay is I was young, my father never really brought us out far better known for his blog and forum at to eat at all the famous hawker places, because he http://ieatishootipost.sg/. With more than believed in home-cooked food. 150,000 unique visitors each month and a busy forum comprising more than 1,000 I started researching on the internet, going to members, Dr Tay is the most read and (online) forums, seeking out people who know influential food blogger in the country. -

Insider People · Places · Events · Dining · Nightlife

APRIL · MAY · JUNE SINGAPORE INSIDER PEOPLE · PLACES · EVENTS · DINING · NIGHTLIFE INSIDE: KATONG-JOO CHIAT HOT TABLES CITY MUST-DOS AND MUCH MORE Ready, set, shop! Shopping is one of Singapore’s national pastimes, and you couldn’t have picked a better time to be here in this amazing city if you’re looking to nab some great deals. Score the latest Spring/Summer goods at the annual Fashion Steps Out festival; discover emerging local and regional designers at trade fair Blueprint; or shop up a storm when The Great Singapore Sale (3 June to 14 August) rolls around. At some point, you’ll want to leave the shops and malls for authentic local experiences in Singapore. Well, that’s where we come in – we’ve curated the best and latest of the city in this nifty booklet to make sure you’ll never want to leave town. Whether you have a week to deep dive or a weekend to scratch the surface, you’ll discover Singapore’s secrets at every turn. There are rich cultural experiences, stylish bars, innovative restaurants, authentic local hawkers, incredible landscapes and so much more. Inside, you’ll find a heap of handy guides – from neighbourhood trails to the best eats, drinks and events in Singapore – to help you make the best of your visit to this sunny island. And these aren’t just our top picks: we’ve asked some of the city’s tastemakers and experts to share their favourite haunts (and then some), so you’ll never have a dull moment exploring this beautiful city we call home. -

Yamazato En Menu.Pdf

グランドメニュー Grand menu Yamazato Speciality Hiyashi Tofu Chilled Tofu Served with Tasty Soy Sauce ¥ 1,300 Agedashi Tofu Deep-fried Tofu with Light Soy Sauce 1,300 Chawan Mushi Japanese Egg Custard 1,400 Tori Kara-age Deep-fried Marinated Chicken 1,800 Nasu Agedashi Deep-fried Eggplant with Light Soy Sauce 2,000 Yasai Takiawase Assorted Simmered Seasonal Vegetables 2,200 Kani Kora-age Deep-fried Crab Shell Stuffed with Minced Crab and Fish Paste 2,800 Main Dish Tempura Moriawase Assorted Tempura ¥ 4,000 Yakiyasai Grilled Assorted Vegetables 2,600 Sawara Yuko Yaki Grilled Spanish Mackerel with Yuzu Flavor 3,000 Saikyo-yaki Grilled Harvest Fish with Saikyo Miso Flavor 3,200 Unagi Kabayaki Grilled Eel with Sweet Soy Sauce 7,800 Yakimono Grilled Fish of the Day current price Yakitori Assorted Chicken Skewers 2,200 Sukini Simmered Sliced Beef with Sukiyaki Sauce 8,500 Wagyu Butter Yaki Grilled Fillet of Beef with Butter Sauce 10,000 Rice and Noodle Agemochi Nioroshi Deep-fried Rice Cake in Grated Radish Soup ¥ 1,700 Tori Zosui Chicken and Egg Rice Porridge 1,300 Yasai Zosui Thin-sliced Vegetables Rice Porridge 1,300 Kani Zosui King Crab and Egg Rice Porridge 1,800 Yasai Udon Udon Noodle Soup with Vegetables 1,500 Yasai Soba Buckwheat Noodle Soup with Vegetables 1,500 Tempura Udon Udon Noodle Soup with Assorted Tempura 5,200 Tempura Soba Buckwheat Noodle Soup with Assorted Tempura 5,200 Tendon Tempura Bowl Served with Miso Soup and Pickles 5,200 Una-jyu Eel Rice in Lacquer Box Served with Miso Soup 8,800 A la Carte Appetizers Yakigoma Tofu Seared -

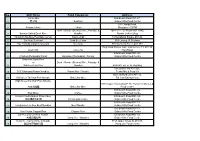

No. Stall Name Food Categories Address

No. Stall Name Food Categories Address Chi Le Ma 505 Beach Road #01-87, 1 吃了吗 Seafood Golden Mile Food Center 307 Changi Road, 2 Katong Laksa Laksa Singapore 419785 Duck / Goose (Stewed) Rice, Porridge & 168 Lor 1 Toa Payoh #01-1040, 3 Benson Salted Duck Rice Noodles Maxim Coffee Shop 4 Kampung Kia Blue Pea Nasi Lemak Nasi Lemak 10 Sengkang Square #01-26 5 Sin Huat Seafood Crab Bee Hoon 659 Lorong 35 Geylang 6 Hoy Yong Seafood Restaurant Cze Cha 352 Clementi Ave 2, #01-153 Haig Road Market and Food Centre, 13, #01-36 7 Chef Chik Cze Cha Haig Road 505 Beach Road #B1-30, 8 Charlie's Peranakan Food Eurasian / Peranakan / Nonya Golden Mile Food Centre Sean Kee Duck Rice or Duck / Goose (Stewed) Rice, Porridge & 9 Sia Kee Duck Rice Noodles 659-661Lor Lor 35 Geylang 665 Buffalo Rd #01-326, 10 545 Whampoa Prawn Noodles Prawn Mee / Noodle Tekka Mkt & Food Ctr 466 Crawford Lane #01-12, 11 Hill Street Tai Hwa Pork Noodle Bak Chor Mee Tai Hwa Eating House High Street Tai Wah Pork Noodle 531A Upper Cross St #02-16, Hong Lim Market & 12 大崋肉脞麵 Bak Chor Mee Food Centre 505 Beach Road #B1-49, 13 Kopi More Coffee Golden Mile Food Centre Hainan Fried Hokkien Prawn Mee 505 Beach Road #B1-34, 14 海南福建炒虾麵 Fried Hokkien Mee Golden Mile Food Centre 505 Beach Road #B1-21, 15 Longhouse Lim Kee Beef Noodles Beef Noodle Golden Mile Food Centre 505 Beach Road #01-73, 16 Yew Chuan Claypot Rice Claypot Rice Golden Mile Food Centre Da Po Curry Chicken Noodle 505 Beach Road #B1-53, 17 大坡咖喱鸡面 Curry Mee / Noodles Golden Mile Food Centre Heng Kee Curry Chicken Noodle 531A -

300Sensational

300 sensational soups Introduction Fresh from the Garden Pumpkin Soup with Leeks and Ginger Butternut Squash Soup with Nutmeg sensational Vegetable Soups Soup Stocks Cream Cream of Artichoke Soup 300 Curried Butternut Squash Soup with Stock Basics Cream of Asparagus Soup White Chicken Stock Toasted Coconut and Golden Raisins Lemony Cream of Asparagus Soup Roasted Winter Squash and Apple Soup Brown Chicken Stock Hot Guacamole Soup with Cumin and Quick Chicken Stock Spicy Winter Squash Soup with Cheddar Cilantro Chile Croutons Chinese Chicken Stock Cream of Broccoli Soup with Bacon Bits Japanese Chicken Stock Pattypan and Summer Squash Soup with Broccoli Buttermilk Soup Avocado and Grape Tomato Salsa Beef Stock Creamy Cabbage and Bacon Soup Veal Stock Tomato Vodka Soup Curry-Spiced Carrot Soup Tomato and Rice Soup with Basil Fish Stock (Fumet) Carrot, Celery and Leek Soup with Shell!sh Stock Roasted Tomato and Pesto Soup Cornbread Dumplings Cream of Roasted Tomato Soup with Ichiban Dashi Carrot, Parsnip and Celery Root Soup soups Grilled Cheese Croutons Miso Stock with Porcini Mushrooms Vegetable Stock Cream of Roasted Turnip Soup with Baby Roasted Cauli"ower Soup with Bacon Bok Choy and Five Spices Roasted Vegetable Stock Cream of Cauli"ower Soup Mushroom Stock Zucchini Soup with Tarragon and Sun- Chestnut Soup with Tru#e Oil Dried Tomatoes Silky Cream of Corn Soup with Chipotle Zucchini Soup with Pancetta and Oven- Chilled Soups Garlic Soup with Aïoli Roasted Tomatoes Almond Gazpacho Garlic Soup with Pesto and Cabbage Cream of Zucchini -

The Food and Culture Around the World Handbook

The Food and Culture Around the World Handbook Helen C. Brittin Professor Emeritus Texas Tech University, Lubbock Prentice Hall Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montreal Toronto Delhi Mexico City Sao Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo Editor in Chief: Vernon Anthony Acquisitions Editor: William Lawrensen Editorial Assistant: Lara Dimmick Director of Marketing: David Gesell Senior Marketing Coordinator: Alicia Wozniak Campaign Marketing Manager: Leigh Ann Sims Curriculum Marketing Manager: Thomas Hayward Marketing Assistant: Les Roberts Senior Managing Editor: Alexandrina Benedicto Wolf Project Manager: Wanda Rockwell Senior Operations Supervisor: Pat Tonneman Creative Director: Jayne Conte Cover Art: iStockphoto Full-Service Project Management: Integra Software Services, Ltd. Composition: Integra Software Services, Ltd. Cover Printer/Binder: Courier Companies,Inc. Text Font: 9.5/11 Garamond Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook appear on appropriate page within text. Copyright © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 07458. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. This publication is protected by Copyright, and permission should be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or likewise. To obtain permission(s) to use material from this work, please submit a written request to Pearson Education, Inc., Permissions Department, 1 Lake Street, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 07458. Many of the designations by manufacturers and seller to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. -

Retailer Address1 Retailer Address2 Retailer Postal Code Trading Name 1 Ang Mo Kio Electronics #01-10 Stall 5 St Enginee 567710

RETAILER_ADDRESS1 RETAILER_ADDRESS2 RETAILER_POSTAL_CODE TRADING NAME 1 ANG MO KIO ELECTRONICS #01-10 STALL 5 ST ENGINEE 567710 WBC 1 ANG MO KIO ELECTRONICS #01-10 STALL 2 ST ENGINEE 567710 WBC 1 ANG MO KIO ELECTRONICS #01-10 STALL 6 ST ENGINEE 567710 WBC 1 ANG MO KIO ELECTRONICS #01-10 STALL 1 ST ENGINEE 567710 WBC 1 ANG MO KIO ELECTRONICS #01-10 STALL 3 ST ENGINEE 567710 WBC 1 ANG MO KIO ELECTRONICS #01-10 STALL 4 ST ENGINEE 567710 WBC FISHBALL 1 ANG MO KIO INDUSTRIAL P ST12 AMK TECH I 568049 FROSTY BITEZ 1 ANG MO KIO INDUSTRIAL P ST11 AMK TECH I 568049 JWZ MUSLIM FOOD 1 AYER CHAWAN PLACE 627871 COMPASS GROUP 1 AYER CHAWAN PLACE ST4 627871 TCEPL-PAC 1 AYER CHAWAN PLACE ST1 627871 TCEPL-PACC 1 AYER CHAWAN PLACE ST2 627871 TCEPL-PACM 1 AYER CHAWAN PLACE ST3 627871 TCEPL-PALB 1 BEACH ROAD #01-4757 BEACH ROAD GARDE 190001 MAKAN MATTERS 1 BEACH ROAD ST01 BEACH ROAD GARDENS 190001 ZF 1 BEVERAGES 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-08 469572 ABU MUBARAK MANDI 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-20 469572 ADAM'S INDIAN ROJAK 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-24 469572 AUNTY JENNY SEAFOOD 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-08 469572 AYAM PENYET NO 1 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-13 469572 FRUITZ DESSERT 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-12 469572 GORENG PISANG KING 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-14 469572 GREEN SKY FRIED KWAY 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-28 469572 MALA WOK 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-15 469572 MALEK SATAY 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-27 469572 NOI KASSIM BBQ 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-07 469572 NUR INDAH KITCHEN 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-18 469572 PERSIAN TANDOOR 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-17 469572 PUTERI NASI PADANG 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-02 469572 SOON LEE FRIED 1 BEDOK ROAD #01-26 469572 SUKA RAMAI MAMA 1 -

Jim Graham's Tar Heel Brunswick Stew

• NORTH CAROLINA WILD GAME COOKERY North Carolina Department of Agriculture James A. Graham, Commissioner POINTS TO REMEMBER IN COOKING WILD GAME (1) Wild game is generally free of fat, therefore. fat must be added or meat will dry out and become difficult to cook. (2) All cooking times must be approximate because each game animal will vary in age and type of food consumed. (3) General rule to follow is that game must be dressed im mediately. cooled down rapidly and kept cool to prevent spoilage from its habitat to the kitchen. North Carolina Department of Agriculture James A. Graham, Commissioner For many years, hunting of wild game has been a sport en joyed across our great State. The problems came with what to do with the game after it was caught and butchered. Recipes are available in two categories, the gourmet which is compli cated both in locating ingredients and procedure, and the generally vague instructions handed down from one hunter to another. The purpose of this publication is to assist the people of our great State in utilizing wild game and increasing con sumption of Tar Heel foods such as sweet potatoes, pickles and corn bread. , TABLE OF CONTENTS BEAR Bear Roast .. .. 4 CATFISH Catfish Gumbo . .. 5 Catfish Steaks 5 Southern Fried Catfish . .. •.....•... .... .. ...... .. .. 6 Catfish Jubilee . 6 DOVES Pan Braised Doves ...... .. ........ ...•... .. .... ... .......... 7 Dove Roast . 7 OPOSSUM Stuffed " Possum" ... ... .•..... ..... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 8 OYSTERS Roasted Oyste rs . .. 9 Oyster Stew ...... .. .. ............ ...... ... ... 9 QUAIL Sausage Stuffed Quail ......... .... .... .• . .......•.... ...... 10 Country Broiled Quail ...... .. .... .. .. .. ..... ...... 10 Bagged Quail .. ......... .. .... ... .. ... .. .. ........ 11 North Carolina Creamed Qu ail .....•.......... .. .. ... .. .... 11 PHEASANT Roast Pheasant ........ -

A Linguistic 'Soup'

Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 48 (4), 2016 A LINGUISTIC ‘SOUP’ AND A SEMANTIC FALSE FRIENDSHIP Alina-Andreea DRAGOESCU, Astrid-Simone GROSZLER Banat University of Agricultural Science and Veterinary Medicine ‘King Michael I of Romania’, Timişoara, Romania 119, Calea Aradului, Timişoara – 300645, Romania [email protected] Abstract. The paper surveys a variety of types of soup, with the purpose of differentiating between the meanings of ‘soup’, ‘broth’ and the Romanian ‘borş’ or the Eastern-European ‘borsh’. A major hypothesis is that Romanian learners of English for specific purposes (in this case students specializing in food services) should discriminate between the meanings of these ‘false friends’ in order to grasp the differences between them correctly. The paper makes reference to the linguistic and semantic differences and similarities between the Romanian and English meanings of ‘soup’ (ciorbă), ‘broth’ (supă) and their derivatives, as well as to the borrowings from other languages (most often French and Asian) containing the word ‘soup’. Keywords: Soup; Noun phrase; Semantic Approach INTRODUCTION Romanians use the noun supă to refer to the simmered stock called broth in English, whereas native speakers of English use the similar-sounding word soup to refer to liquids exhibiting distinctively different features – for instance containing ingredients like meet and an infinite range of vegetables. This linguistic ‘false friendship’ has resulted in a series of confounding misunderstandings that need to be clarified through cross-cultural and linguistic input and acquisition. MATERIAL AND METHODS A limited number of noun phrases containing the word soup have been inventoried by using language dictionaries, encyclopaedias, cookbooks and food dictionaries such as Bender & Bender’s and Sinclair’s, as well as the comprehensive Webster’s Dictionary. -

BACK to SCHOOL TRENDS Es2 Complied by Valerie Kellogg Hop Liv Ts

JUNE 28, 2020 Special Advertising Feature BACK TO TIE-DYE SCHOOL TRENDS omfort is key, thanks to the C dress-down pandemic, say Long Island retailers. Whether the kids are in the classroom or not, the oh-so-casual look should serve them well. —Valerie Kellogg WHITE KICKS CONCERT Ts RAINBOWS STICKERSERS LOOK INSIDE FOR MORE FALL ADVICE Photos: clockwise from top, Charlotte Coté, Target, @turtlesoup, Rowdy Sprout and Nike 2159819001215 2159819001 F2 BACK TO SCHOOL TRENDS eS2 Complied by Valerie Kellogg hop Liv tS Ea MULLET The low-maintenance but “new- and-improved” mullet is an example of the laid-back style tweens and teens are looking in for, says Tracy Messina, ng marketing and public relations Lo manager for the JD Thomas & wn Da Co. Salon (6168 Jericho Tpke., Commack, 631-486-4443, WHITE KICKS jdthomasandco.com). Braids are also big, oftentimes with Another classic is new again at streaksof c coloolorr,, shshee says.says. Renarts East Northport (2060 Jericho Tpke., East Northport, 631-493-2333, renarts.com) – the Nike Air Force 1 ($80 and up) in the white colorway. Kids like that the sneakers are easy to style and wear and go with anything, Nike says Jordan Chan, manager. RAINBOWS This rainbow case ($4.99 at Target stores) from More Than Magic contains six pencils with inspirational sayings, including, “It’s cool to be kind.” Ta rg et STICKERS Tu Everyone seems to be into stickers now, most especially tweens rtle’s @tur Soup / and teens (and college students, too). This removable, waterproof tless oup bookworm sticker ($3.99 each) from Turtle’s Soup is part of a line that is popular for using on phones, laptops, walls, sneakers, school BELLPORTBELLPORT computers, everything, says Lori Badanes, who carries them at Einstein’s Attic (79 Main St., Northport, 631-261-7564, einsteinsatticnorthport.com). -

$149 $599 $299 $199 $350

WeW AreAre LocallyLocalllly OOwnedwnedd and Proud to Support Our Neighboring Companies In The Deli Kahn’s Deluxe Club $ 99 Bologna 1 Lb. 9.5 Oz. Husman’s Potato Chips or 8-9 Oz. Snyder of Berlin Kettle Chips or 12 Oz. Snyder of Berlin $ Pretzel Rods 2/ 5 13 Oz. Skyline Frozen Chili $ 50 or Chili & Spaghetti 3 14 Oz. BlueGrass Bratwurst or $ 99 Mettwurst 2 20 Oz. LaRosa’s $ 99 Lasagna 5 10 Oz. Can Worthmore $ 49 Mock Turtle Soup 1 18 Oz. Montgomery Inn $ Barbecue Sauce 2/ 5 NAPMG_5068 NAPMG_5068_5241_5070_GATEFR_110616_4C ChickenMeal Deal 8 Piece Fried or Whole Rotisserie Chicken $10 99 CHOOSE (2) 1 LB. SIDES FROM Potato Salad, Cole Slaw, Macaroni Salad, Mashed Potatoes & Gravy and 4 Dinner Rolls Introducing Máka Mia Pizza or Hoagies Not Available At Ros s Fresh Dough, 100% Cheese & Freshness Toppings 12 Inch 1 Topping Pizza, Subs or Hoagies 2/$9 or $4$$4.999999 EEa. NAPMG_5086 NAPMG_5086_5241_5070_GATEBK_110616_4C YOUR HOMETOWN MARKET EEarlyarly BirdBirdSSaleale 110-200-20 LLbs.bs. FFrozenrozen HHoneysuckleoneysuckle ¢ Turkeys 99Lb. Limit 2 with additional $25 purchase. Hurry While Supples Last WWholehole oorr HHalfalf FFrozenrozen BBestest CChoicehoice CCliftylifty FFarmarm HHoneysuckleoneysuckle WWhitehite SSpiralpiral SSlicedliced HHamam WWholehole CCountryountry HHamsams TTurkeyurkey BBreastreast $ 9999 $ 9999 $ 5599 1 LLb.b. 1 LLb.b. 1 LLb.b. Extra Large Ney York Green Strip Bell Peppers Steaks $ $ 99 2/ 1 5 Lb. Family Pack Sanderson Farms Family Pack All Natural Split Fryer Whole Boneless Ground $ 49 Whole $ 19 Chicken $ 39 New York $ 99 Chuck 2 Lb. Pork Butts 1 Lb.Breasts 1 Lb.Strip Loin 4 Lb. Peruvian Sunkist Sweet Navel Onions Oranges ¢ $ 89Lb.