California, Mexico'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

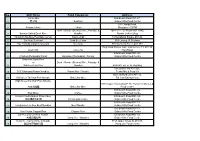

Seafood Soup & Salad Meats Vegetables Extras

SOUP & SALAD SEAFOOD MEATS Miso Tuna Salad Turtle Soup Certified Japanese Wagyu miso marinated tuna, spicy tuna carpaccio, topped with sherry 9 / 18 ruby red grapefruit ponzu and crispy shallots spinach and wakame salad, dashi vinaigrette, 14 per oz (3 oz minimum) Fried Chicken & Andouille Gumbo sesame chip 14 a la Chef Paul 9 Fried Smoked Oysters Grilled Sweetbreads bourbon tomato jam, white remoulade 14 charred polenta cake, sherry braised cipollini Pickled Shrimp Salad onion, chimmichurri, sauce soubise 15 lolla rosa, Creole mustard vinaigrette, Crabmeat Spaetzle Italian cherry peppers, Provolone, prosciutto, Creole mustard dumplings, jumbo lump crab, Beef Barbacoa Sopes roasted corn, green tomato chow chow 10 / 20 green garbanzos, brown butter 12 crispy masa shell, red chili braised beef, queso fresco, pickled vegetables, avocado crema 11 City Park Salad Brown Butter Glazed Flounder & Crab baby red oak, romaine, granny smith apples, almond butter, green beans, lemon gelée, Golden City Lamb Ribs Stilton blue, applewood smoked bacon 8 / 16 almond wafer 16 Mississippi sorghum & soy glaze, fermented bean paste, charred cabbage, BBQ Shrimp Agnolotti Cheese Plate fried peanuts 13 / 26 chef’s selection of cheeses, quince paste, white stuffed pasta, BBQ and cream cheese filling, truffle honey, hazelnuts & water crackers 15 lemon crème fraîche, Gulf shrimp 13 / 26 Vadouvan Shrimp & Grits Rabbit Sauce Piquante vadouvan, garam masala, broken rice grits, slow braised leg, tasso jambalaya stuffing, VEGETABLES housemade chili sauce, fresh yogurt -

The Good Food Doctor: Heeats•Hesh Ots•Heposts

20 Interview By Dr Hsu Li Yang, Editorial Board Member The Good Food Doctor: heeats•hesh ots•heposts... Hsu Li Yang (HLY): Leslie, thank you very much for agreeing to participate in this interview with the SMA News. What made you start this “ieatishootipost” food blog? Dr Leslie Tay (LT): I had been overseas for a long time and when I finally came back to Singapore, I began to appreciate just how much of a Singaporean I really am. You know, my perfect breakfast would be two roti prata with a cup of teh tarik or kopi and kaya toast. Sometimes I feel we take our very own Singapore food for granted, that is, until we live overseas. About two years ago, I suddenly felt that even is day job is that of a family doctor though I love Singapore food, I don’t really know (one of two founding partners where all the good stuff is – where’s the best hokkien mee, the best chicken rice and so on. So I decided, of Karri Family Clinic) in the H okay, let’s go and try all these food as a hobby. When Tampines heartlands. But Dr Leslie Tay is I was young, my father never really brought us out far better known for his blog and forum at to eat at all the famous hawker places, because he http://ieatishootipost.sg/. With more than believed in home-cooked food. 150,000 unique visitors each month and a busy forum comprising more than 1,000 I started researching on the internet, going to members, Dr Tay is the most read and (online) forums, seeking out people who know influential food blogger in the country. -

Whale Shark Rhincodon Typus Populations Along the West Coast of the Gulf of California and Implications for Management

Vol. 18: 115–128, 2012 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online August 16 doi: 10.3354/esr00437 Endang Species Res Whale shark Rhincodon typus populations along the west coast of the Gulf of California and implications for management Dení Ramírez-Macías1,2,*, Abraham Vázquez-Haikin3, Ricardo Vázquez-Juárez1 1Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, Mar Bermejo 195, Col. Playa Palo de Santa Rita, La Paz, Baja California Sur 23096, Mexico 2Tiburón Ballena México de Conciencia México, Manatí 4802, Col. Esperanza III, La Paz, Baja California Sur 23090, Mexico 3Asociación de Pesca Deportiva y Ecoturismo de Bahía de los Ángeles, Domicilio conocido Bahía de los Ángeles, Baja California 22980, Mexico ABSTRACT: We used photo-identification data collected from 2003 through 2009 to estimate pop- ulation structure, site fidelity, abundance, and movements of this species along the west coast of the Gulf of California to make recommendations for effective conservation and management. Of 251 whale sharks identified from 1784 photographs, 129 sharks were identified in Bahía de Los Ángeles and 125 in Bahía de La Paz. Only juveniles (mostly small) were found in these 2 bays. At Isla Espíritu Santo, we identified adult females; at Gorda Banks we identified 15 pregnant females. High re-sighting rates within and across years provided evidence of site fidelity among juvenile sharks in the 2 bays. Though the juveniles were not permanent residents, they used the areas regularly from year to year. A proportion of the juveniles spent days to a month or more in the coastal waters of the 2 bays before leaving, and periods of over a month outside the study areas before entering the bays again. -

Insider People · Places · Events · Dining · Nightlife

APRIL · MAY · JUNE SINGAPORE INSIDER PEOPLE · PLACES · EVENTS · DINING · NIGHTLIFE INSIDE: KATONG-JOO CHIAT HOT TABLES CITY MUST-DOS AND MUCH MORE Ready, set, shop! Shopping is one of Singapore’s national pastimes, and you couldn’t have picked a better time to be here in this amazing city if you’re looking to nab some great deals. Score the latest Spring/Summer goods at the annual Fashion Steps Out festival; discover emerging local and regional designers at trade fair Blueprint; or shop up a storm when The Great Singapore Sale (3 June to 14 August) rolls around. At some point, you’ll want to leave the shops and malls for authentic local experiences in Singapore. Well, that’s where we come in – we’ve curated the best and latest of the city in this nifty booklet to make sure you’ll never want to leave town. Whether you have a week to deep dive or a weekend to scratch the surface, you’ll discover Singapore’s secrets at every turn. There are rich cultural experiences, stylish bars, innovative restaurants, authentic local hawkers, incredible landscapes and so much more. Inside, you’ll find a heap of handy guides – from neighbourhood trails to the best eats, drinks and events in Singapore – to help you make the best of your visit to this sunny island. And these aren’t just our top picks: we’ve asked some of the city’s tastemakers and experts to share their favourite haunts (and then some), so you’ll never have a dull moment exploring this beautiful city we call home. -

Ii \ T MEXICAN GRASSES in the UNITED STATES NATIONAL

■ . ~+j-,r?7-w- - i i - . \ t MEXICAN GRASSES IN THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL HERBARIUM. By A. S, Hitchcock INTRODUCTION. The following list of grasses, based entirely upon specimens in the United States National Herbarium, is a preliminary paper, in which the scattered data upon Mexican grasses have been brought together and arranged in a convenient form. The species included have been accepted, for the most part, in their traditional sense. It has been impracticable to examine the types of many of the earlier described species since these specimens are located in European herbaria. For this reason the synonymy has been confined mostly to those names that could be fixed by an examination of American types, or concerning the application of which there was little doubt. The largest number of unidentified names are found in Fournier's work on Mexican grasses.1 This results from the incomplete or unsatis- factory descriptions and from the fact that the specimens cited under a given species either may not agree with the diagnosis, or may belong to two or more species, at least in different herbaria. An examination of the original specimens will undoubtedly lead to the identification of the greater part of these names. There are several specimens that have been omitted from the list because they have not been identified and are apparently unde- scribed species. They belong to genera, however, that are much in need of critical revision and further study of them is deferred for the present. In subsequent articles it is hoped to work out the classifi- cation of the tropical American grasses upon a type basis KEY TO THE GENEBA. -

Radiocarbon Ages of Lacustrine Deposits in Volcanic Sequences of the Lomas Coloradas Area, Socorro Island, Mexico

Radiocarbon Ages of Lacustrine Deposits in Volcanic Sequences of the Lomas Coloradas Area, Socorro Island, Mexico Item Type Article; text Authors Farmer, Jack D.; Farmer, Maria C.; Berger, Rainer Citation Farmer, J. D., Farmer, M. C., & Berger, R. (1993). Radiocarbon ages of lacustrine deposits in volcanic sequences of the Lomas Coloradas area, Socorro Island, Mexico. Radiocarbon, 35(2), 253-262. DOI 10.1017/S0033822200064924 Publisher Department of Geosciences, The University of Arizona Journal Radiocarbon Rights Copyright © by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona. All rights reserved. Download date 28/09/2021 10:52:25 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/653375 [RADIOCARBON, VOL. 35, No. 2, 1993, P. 253-262] RADIOCARBON AGES OF LACUSTRINE DEPOSITS IN VOLCANIC SEQUENCES OF THE LOMAS COLORADAS AREA, SOCORRO ISLAND, MEXICO JACK D. FARMERI, MARIA C. FARMER2 and RAINER BERGER3 ABSTRACT. Extensive eruptions of alkalic basalt from low-elevation fissures and vents on the southern flank of the dormant volcano, Cerro Evermann, accompanied the most recent phase of volcanic activity on Socorro Island, and created 14C the Lomas Coloradas, a broad, gently sloping terrain comprising the southern part of the island. We obtained ages of 4690 ± 270 BP (5000-5700 cal BP) and 5040 ± 460 BP (5300-6300 cal BP) from lacustrine deposits that occur within volcanic sequences of the lower Lomas Coloradas. Apparently, the sediments accumulated within a topographic depression between two scoria cones shortly after they formed. The lacustrine environment was destroyed when the cones were breached by headward erosion of adjacent stream drainages. -

Parque Nacional Revillagigedo

EVALUATION REPORT Parque Nacional Revillagigedo Location: Revillagigedo Archipelago, Mexico, Eastern Pacific Ocean Blue Park Status: Nominated (2020), Evaluated (2021) MPAtlas.org ID: 68808404 Manager(s): Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) MAPS 2 1. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA 1.1 Biodiversity Value 4 1.2 Implementation 8 2. AWARD STATUS CRITERIA 2.1 Regulations 11 2.2 Design, Management, and Compliance 13 3. SYSTEM PRIORITIES 3.1 Ecosystem Representation 18 3.2 Ecological Spatial Connectivity 18 SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION: Evidence of MPA Effects 19 Figure 1: Revillagigedo National Park, located 400 km south of Mexico’s Baja peninsula, covers 148,087 km2 and includes 3 zone types – Research (solid blue), Tourism (dotted), and Traditional Use/Naval (lined) – all of which ban all extractive activities. It is partially surrounded by the Deep Mexican Pacific Biosphere Reserve (grey) which protects the water column below 800 m. All 3 zones of the National Park are shown in the same shade of dark blue, reflecting that they all have Regulations Based Classification scores ≤ 3, corresponding with a fully protected status (see Section 2.1 for more information about the regulations associated with these zones). (Source: MPAtlas, Marine Conservation Institute) 2 Figure 2: Three-dimensional map of the Revillagigedo Marine National Park shows the bathymetry around Revillagigedo’s islands. (Source: Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, 2018) 3 1.1 Eligibility Criteria: Biodiversity Value (must satisfy at least one) 1.1.1. Includes rare, unique, or representative ecosystems. The Revillagigedo Archipelago is comprised of a variety of unique ecosystems, due in part to its proximity to the convergence of five tectonic plates. -

Archipiélago De Revillagigedo

LATIN AMERICA / CARIBBEAN ARCHIPIÉLAGO DE REVILLAGIGEDO MEXICO Manta birostris in San Benedicto - © IUCN German Soler Mexico - Archipiélago de Revillagigedo WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION – IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION ARCHIPIÉLAGO DE REVILLAGIGEDO (MEXICO) – ID 1510 IUCN RECOMMENDATION TO WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: To inscribe the property under natural criteria. Key paragraphs of Operational Guidelines: Paragraph 77: Nominated property meets World Heritage criteria (vii), (ix) and (x). Paragraph 78: Nominated property meets integrity and protection and management requirements. 1. DOCUMENTATION (2014). Evaluación de la capacidad de carga para buceo en la Reserva de la Biosfera Archipiélago de a) Date nomination received by IUCN: 16 March Revillagigedo. Informe Final para la Direción de la 2015 Reserva de la Biosiera, CONANP. La Paz, B.C.S. 83 pp. Martínez-Gomez, J. E., & Jacobsen, J.K. (2004). b) Additional information officially requested from The conservation status of Townsend's shearwater and provided by the State Party: A progress report Puffinus auricularis auricularis. Biological Conservation was sent to the State Party on 16 December 2015 116(1): 35-47. Spalding, M.D., Fox, H.E., Allen, G.R., following the IUCN World Heritage Panel meeting. The Davidson, N., Ferdaña, Z.A., Finlayson, M., Halpern, letter reported on progress with the evaluation process B.S., Jorge, M.A., Lombana, A., Lourie, S.A., Martin, and sought further information in a number of areas K.D., McManus, E., Molnar, J., Recchia, C.A. & including the State Party’s willingness to extend the Robertson, J. (2007). Marine ecoregions of the world: marine no-take zone up to 12 nautical miles (nm) a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. -

Yamazato En Menu.Pdf

グランドメニュー Grand menu Yamazato Speciality Hiyashi Tofu Chilled Tofu Served with Tasty Soy Sauce ¥ 1,300 Agedashi Tofu Deep-fried Tofu with Light Soy Sauce 1,300 Chawan Mushi Japanese Egg Custard 1,400 Tori Kara-age Deep-fried Marinated Chicken 1,800 Nasu Agedashi Deep-fried Eggplant with Light Soy Sauce 2,000 Yasai Takiawase Assorted Simmered Seasonal Vegetables 2,200 Kani Kora-age Deep-fried Crab Shell Stuffed with Minced Crab and Fish Paste 2,800 Main Dish Tempura Moriawase Assorted Tempura ¥ 4,000 Yakiyasai Grilled Assorted Vegetables 2,600 Sawara Yuko Yaki Grilled Spanish Mackerel with Yuzu Flavor 3,000 Saikyo-yaki Grilled Harvest Fish with Saikyo Miso Flavor 3,200 Unagi Kabayaki Grilled Eel with Sweet Soy Sauce 7,800 Yakimono Grilled Fish of the Day current price Yakitori Assorted Chicken Skewers 2,200 Sukini Simmered Sliced Beef with Sukiyaki Sauce 8,500 Wagyu Butter Yaki Grilled Fillet of Beef with Butter Sauce 10,000 Rice and Noodle Agemochi Nioroshi Deep-fried Rice Cake in Grated Radish Soup ¥ 1,700 Tori Zosui Chicken and Egg Rice Porridge 1,300 Yasai Zosui Thin-sliced Vegetables Rice Porridge 1,300 Kani Zosui King Crab and Egg Rice Porridge 1,800 Yasai Udon Udon Noodle Soup with Vegetables 1,500 Yasai Soba Buckwheat Noodle Soup with Vegetables 1,500 Tempura Udon Udon Noodle Soup with Assorted Tempura 5,200 Tempura Soba Buckwheat Noodle Soup with Assorted Tempura 5,200 Tendon Tempura Bowl Served with Miso Soup and Pickles 5,200 Una-jyu Eel Rice in Lacquer Box Served with Miso Soup 8,800 A la Carte Appetizers Yakigoma Tofu Seared -

Echinoderm Research and Diversity in Latin America

Echinoderm Research and Diversity in Latin America Bearbeitet von Juan José Alvarado, Francisco Alonso Solis-Marin 1. Auflage 2012. Buch. XVII, 658 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 642 20050 2 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 1239 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Chemie, Biowissenschaften, Agrarwissenschaften > Biowissenschaften allgemein > Ökologie Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Chapter 2 The Echinoderms of Mexico: Biodiversity, Distribution and Current State of Knowledge Francisco A. Solís-Marín, Magali B. I. Honey-Escandón, M. D. Herrero-Perezrul, Francisco Benitez-Villalobos, Julia P. Díaz-Martínez, Blanca E. Buitrón-Sánchez, Julio S. Palleiro-Nayar and Alicia Durán-González F. A. Solís-Marín (&) Á M. B. I. Honey-Escandón Á A. Durán-González Laboratorio de Sistemática y Ecología de Equinodermos, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología (ICML), Colección Nacional de Equinodermos ‘‘Ma. E. Caso Muñoz’’, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Apdo. Post. 70-305, 04510, México, D.F., México e-mail: [email protected] A. Durán-González e-mail: [email protected] M. B. I. Honey-Escandón Posgrado en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología (ICML), UNAM, Apdo. Post. 70-305, 04510, México, D.F., México e-mail: [email protected] M. D. Herrero-Perezrul Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Ave. -

No. Stall Name Food Categories Address

No. Stall Name Food Categories Address Chi Le Ma 505 Beach Road #01-87, 1 吃了吗 Seafood Golden Mile Food Center 307 Changi Road, 2 Katong Laksa Laksa Singapore 419785 Duck / Goose (Stewed) Rice, Porridge & 168 Lor 1 Toa Payoh #01-1040, 3 Benson Salted Duck Rice Noodles Maxim Coffee Shop 4 Kampung Kia Blue Pea Nasi Lemak Nasi Lemak 10 Sengkang Square #01-26 5 Sin Huat Seafood Crab Bee Hoon 659 Lorong 35 Geylang 6 Hoy Yong Seafood Restaurant Cze Cha 352 Clementi Ave 2, #01-153 Haig Road Market and Food Centre, 13, #01-36 7 Chef Chik Cze Cha Haig Road 505 Beach Road #B1-30, 8 Charlie's Peranakan Food Eurasian / Peranakan / Nonya Golden Mile Food Centre Sean Kee Duck Rice or Duck / Goose (Stewed) Rice, Porridge & 9 Sia Kee Duck Rice Noodles 659-661Lor Lor 35 Geylang 665 Buffalo Rd #01-326, 10 545 Whampoa Prawn Noodles Prawn Mee / Noodle Tekka Mkt & Food Ctr 466 Crawford Lane #01-12, 11 Hill Street Tai Hwa Pork Noodle Bak Chor Mee Tai Hwa Eating House High Street Tai Wah Pork Noodle 531A Upper Cross St #02-16, Hong Lim Market & 12 大崋肉脞麵 Bak Chor Mee Food Centre 505 Beach Road #B1-49, 13 Kopi More Coffee Golden Mile Food Centre Hainan Fried Hokkien Prawn Mee 505 Beach Road #B1-34, 14 海南福建炒虾麵 Fried Hokkien Mee Golden Mile Food Centre 505 Beach Road #B1-21, 15 Longhouse Lim Kee Beef Noodles Beef Noodle Golden Mile Food Centre 505 Beach Road #01-73, 16 Yew Chuan Claypot Rice Claypot Rice Golden Mile Food Centre Da Po Curry Chicken Noodle 505 Beach Road #B1-53, 17 大坡咖喱鸡面 Curry Mee / Noodles Golden Mile Food Centre Heng Kee Curry Chicken Noodle 531A -

300Sensational

300 sensational soups Introduction Fresh from the Garden Pumpkin Soup with Leeks and Ginger Butternut Squash Soup with Nutmeg sensational Vegetable Soups Soup Stocks Cream Cream of Artichoke Soup 300 Curried Butternut Squash Soup with Stock Basics Cream of Asparagus Soup White Chicken Stock Toasted Coconut and Golden Raisins Lemony Cream of Asparagus Soup Roasted Winter Squash and Apple Soup Brown Chicken Stock Hot Guacamole Soup with Cumin and Quick Chicken Stock Spicy Winter Squash Soup with Cheddar Cilantro Chile Croutons Chinese Chicken Stock Cream of Broccoli Soup with Bacon Bits Japanese Chicken Stock Pattypan and Summer Squash Soup with Broccoli Buttermilk Soup Avocado and Grape Tomato Salsa Beef Stock Creamy Cabbage and Bacon Soup Veal Stock Tomato Vodka Soup Curry-Spiced Carrot Soup Tomato and Rice Soup with Basil Fish Stock (Fumet) Carrot, Celery and Leek Soup with Shell!sh Stock Roasted Tomato and Pesto Soup Cornbread Dumplings Cream of Roasted Tomato Soup with Ichiban Dashi Carrot, Parsnip and Celery Root Soup soups Grilled Cheese Croutons Miso Stock with Porcini Mushrooms Vegetable Stock Cream of Roasted Turnip Soup with Baby Roasted Cauli"ower Soup with Bacon Bok Choy and Five Spices Roasted Vegetable Stock Cream of Cauli"ower Soup Mushroom Stock Zucchini Soup with Tarragon and Sun- Chestnut Soup with Tru#e Oil Dried Tomatoes Silky Cream of Corn Soup with Chipotle Zucchini Soup with Pancetta and Oven- Chilled Soups Garlic Soup with Aïoli Roasted Tomatoes Almond Gazpacho Garlic Soup with Pesto and Cabbage Cream of Zucchini