Faces of Africa: Diversity and Progress; Repression and Struggle, Report of Special Study Missions to Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Address List of South Africans Banned and Banished for Opposition to Apartheid and of Families of Political Prisoners

Address List of South Africans Banned and Banished for Opposition to Apartheid and of Families of Political Prisoners http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1971_45 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Address List of South Africans Banned and Banished for Opposition to Apartheid and of Families of Political Prisoners Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 48/71 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Contributor Anti-Apartheid Movement Publisher Department of Political and Security Council Affairs Date 1971-11-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, United Kingdom Coverage (temporal) 1971 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Contains a list of addresses provided by the Anti-Apartheid Movement. -

Mozambican Revolution, No. 9

Mozambican Revolution, No. 9 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.numr196408 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Mozambican Revolution, No. 9 Alternative title Mozambique Revolution Author/Creator Mozambique Liberation Front - FRELIMO Contributor Department of Information [FRELIMO] Publisher Mozambique Liberation Front - FRELIMO Date 1964-08 Resource type Magazines (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Mozambique Coverage (temporal) 1964 Source Northwestern University Library, L967.905 M939 Rights By kind permission of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO). Description Editorial; Expulsion of Leo Milas from FRELIMO; Portugese Ropressive measures against the Mozambican people; Cooperation between imperialists; Pipeline Link betvween Mozambique and S. -

Rapport EV 2009 Cartes Rev-Mai 2011 Mb MF__Dsdsx

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi ---------- MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES ---------- Cellule de Suivi du Programme de Lutte contre la Pauvreté (CSPLP) ---------- Projet d’Appui à la Stratégie de Réduction de la Pauvreté (PASRP) Avec l’appui de l’union européenne ENQUETE VILLAGES DE 2009 SUR L'ACCES AUX SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE Rapport final Dakar, Décembre 2009 SOMMAIRE I. CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATIONS _____________________________________________ 3 II. OBJECTIF GLOBAL DE L’ENQUETE VILLAGES __________________________________ 3 III. ORGANISATION ET METHODOLOGIE ________________________________________ 5 III.1 Rationalité ______________________________________________________________ 5 III.2 Stratégie ________________________________________________________________ 5 III.3 Budget et ressources humaines _____________________________________________ 7 III.4 Calendrier des activités ____________________________________________________ 7 III.5 Calcul des indices et classement des communautés rurales _______________________ 9 IV. Analyse des premiers résultats de l’enquête _______________________________ 10 V. ACCES ET EXISTENCE DES SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE _________________________ 11 VI. Accès et fonctionnalité des services sociaux de base ________________________ 14 VII. Disparités régionales et accès aux services sociaux de base __________________ 16 VII.1 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un lieu de commerce ___________________________ 16 VII.2 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un point d’eau potable _________________________ -

South Africa: Change and Confrontation, Report of a Study Mission to South Africa

South Africa: Change and Confrontation, Report of a Study Mission to South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.uscg015 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org South Africa: Change and Confrontation, Report of a Study Mission to South Africa Alternative title South Africa: Change and Confrontation, Report of a Study Mission to South Africa Author/Creator Committee on Foreign Affairs; House of Representatives Publisher U.S. Government Printing Office Date 1980-07-00 Resource type Hearings Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, United States Source Congressional Hearings and Mission Reports: U.S. -

Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa's Dominant

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 © Copyright by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System by Safia Abukar Farole Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Kathleen Bawn, Chair In countries ruled by a single party for a long period of time, how does political opposition to the ruling party grow? In this dissertation, I study the growth in support for the Democratic Alliance (DA) party, which is the largest opposition party in South Africa. South Africa is a case of democratic dominant party rule, a party system in which fair but uncompetitive elections are held. I argue that opposition party growth in dominant party systems is explained by the strategies that opposition parties adopt in local government and the factors that shape political competition in local politics. I argue that opposition parties can use time spent in local government to expand beyond their base by delivering services effectively and outperforming the ruling party. I also argue that performance in subnational political office helps opposition parties build a reputation for good governance, which is appealing to ruling party ii. supporters who are looking for an alternative. Finally, I argue that opposition parties use candidate nominations for local elections as a means to appeal to constituents that are vital to the ruling party’s coalition. -

CULL0001-2-32-01-Jpeg.Pdf

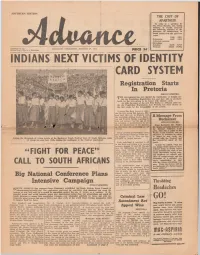

SOUTHERN EDITION THE COST OF APARTHEID In reply to a question by Mr. Brian Bunting, the Acting Minister of Health disclosed the following Statistics of the incidence of tuberculosis in South Africa over the past four years: 1948 1952 Europeans 1,609 1,422 Coloured persons (including w d v a a c e Asiatics) 5,478 5,715 Africans 15,681 20,942 Registered at tbe ADVANCE, THURSDAY, AUGUST 27, 1953 G eneral Past* Cfilce as a Newspaper PRICE 3d INDIANS NEXT VICTIMS OF IDENTITY CARD SYSTEM Registration Starts In Pretoria JOHANNESBURG. rpH E Government has now started the registration of Indians un- der the Population Registration Act, and they will, in all likeli hood, be the next group to be issued with identity cards. As with the issue of the new Pass Books to Africans (also un der the Population Registration Act) Pretoria has been chosen as the first centre for the inauguration of the system. A notice has been issued to Asia tics (in this group fall Indians, Chi nese and Malays) in Pretoria and the townships of East Lynne, Silver- A Message From ton and Pretoria North, requiring all Bucharest men and women over the age of 16 to complete a questionnaire to en JOHANNESBURG. able the Department of the Interior From Bucharest Mr. Walter to determine the citizenship oc all M. Sisulu, secretary-general of Asiatics. the African National Con gress, who was a guest of the These printed questionnaire forms World Youth Festival, sent an were distributed house to house dur interview to Advance in which ing August 12 to 21. -

Independence, Intervention, and Internationalism Angola and the International System, 1974–1975

Independence, Intervention, and Internationalism Angola and the International System, 1974–1975 ✣ Candace Sobers Mention the Cold War and thoughts instinctively turn to Moscow, Washing- ton, DC, and Beijing. Fewer scholars examine the significant Cold War strug- gles that took place in the African cities of Luanda, Kinshasa, and Pretoria. Yet in 1975 a protracted war of national liberation on the African continent escalated sharply into a major international crisis. Swept up in the momen- tum of the Cold War, the fate of the former Portuguese colony of Angola captured the attention of policymakers from the United States to Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), Colombia to Luxembourg. The struggle over Angolan independence from Portugal was many things: the culmination of sixteen years of intense anti-colonial struggle and the launch of 28 years of civil war, a threat to white minority rule in southern Africa, and another battle on the long road to ending empire and colonialism. It was also a strug- gle to define and create a viable postcolonial state and to carry out a radical transformation of the sociopolitical structure of Angolan society. Recent scholarship on Angolan independence has provided an impres- sive chronology of the complicated saga yet has less to say about the wider consequences and ramifications of a crisis that, though located in southern Africa, was international in scope. During the anti-colonial struggle, U.S. sup- port reinforced the Portuguese metropole, contiguous African states harbored competing revolutionaries, and great and medium powers—including Cuba, China, and South Africa—provided weapons, combat troops, and mercenar- ies to the three main national liberation movements. -

Les Resultats Aux Examens

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar OFFICE DU BACCALAUREAT B.P. 5005 - Dakar-Fann – Sénégal Tél. : (221) 338593660 - (221) 338249592 - (221) 338246581 - Fax (221) 338646739 Serveur vocal : 886281212 RESULTATS DU BACCALAUREAT SESSION 2017 Janvier 2018 Babou DIAHAM Directeur de l’Office du Baccalauréat 1 REMERCIEMENTS Le baccalauréat constitue un maillon important du système éducatif et un enjeu capital pour les candidats. Il doit faire l’objet d’une réflexion soutenue en vue d’améliorer constamment son organisation. Ainsi, dans le souci de mettre à la disposition du monde de l’Education des outils d’évaluation, l’Office du Baccalauréat a réalisé ce fascicule. Ce fascicule représente le dix-septième du genre. Certaines rubriques sont toujours enrichies avec des statistiques par type de série et par secteur et sous - secteur. De même pour mieux coller à la carte universitaire, les résultats sont présentés en cinq zones. Le fascicule n’est certes pas exhaustif mais les utilisateurs y puiseront sans nul doute des informations utiles à leur recherche. Le Classement des établissements est destiné à satisfaire une demande notamment celle de parents d'élèves. Nous tenons à témoigner notre sincère gratitude aux autorités ministérielles, rectorales, académiques et à l’ensemble des acteurs qui ont contribué à la réussite de cette session du Baccalauréat. Vos critiques et suggestions sont toujours les bienvenues et nous aident -

The Referendum in FW De Klerk's War of Manoeuvre

The referendum in F.W. de Klerk’s war of manoeuvre: An historical institutionalist account of the 1992 referendum. Gary Sussman. London School of Economics and Political Science. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and International History, 2003 UMI Number: U615725 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615725 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h e s e s . F 35 SS . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract: This study presents an original effort to explain referendum use through political science institutionalism and contributes to both the comparative referendum and institutionalist literatures, and to the political history of South Africa. Its source materials are numerous archival collections, newspapers and over 40 personal interviews. This study addresses two questions relating to F.W. de Klerk's use of the referendum mechanism in 1992. The first is why he used the mechanism, highlighting its role in the context of the early stages of his quest for a managed transition. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project STEVE McDONALD Interviewed by: Dan Whitman Initial Interview Date: August 17, 2011 Copyright 2018 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Education MA, South African Policy Studies, University of London 1975 Joined Foreign Service 1975 Washington, DC 1975 Desk Officer for Portuguese African Colonies Pretoria, South Africa 1976-1979 Political Officer -- Black Affairs Retired from the Foreign Service 1980 Professor at Drury College in Missouri 1980-1982 Consultant, Ford Foundation’s Study 1980-1982 “South Africa: Time Running Out” Head of U.S. South Africa Leadership Exchange Program 1982-1987 Managed South Africa Policy Forum at the Aspen Institute 1987-1992 Worked for African American Institute 1992-2002 Consultant for the Wilson Center 2002-2008 Consulting Director at Wilson Center 2009-2013 INTERVIEW Q: Here we go. This is Dan Whitman interviewing Steve McDonald at the Wilson Center in downtown Washington. It is August 17. Steve McDonald, you are about to correct me the head of the Africa section… McDONALD: Well the head of the Africa program and the project on leadership and building state capacity at the Woodrow Wilson international center for scholars. 1 Q: That is easy for you to say. Thank you for getting that on the record, and it will be in the transcript. In the Wilson Center many would say the prime research center on the East Coast. McDONALD: I think it is true. It is a think tank a research and academic body that has approximately 150 fellows annually from all over the world looking at policy issues. -

A History of the Progressive Federal Party, 1981 - 1989

STRUCTURAL CRISIS AND LIBERALISM: A HISTORY OF THE PROGRESSIVE FEDERAL PARTY, 1981 - 1989 DAVID SHANDLER Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Economic History, Faculty of Arts, University of Cape Town, January 1991 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. .ABSTRACT Whereas an extensive literature has developed on the broad conditions of crisis in South Africa in the seventies and eighties, and on the dynamic of state and popular responses to it, little focus has fallen .on the reactions . of the other key elements among the dominating classes. It is the aim of this dissertation to attempt to address an aspect of this lacuna by focussing on the Progressive Federal Party's responses from 1981 until 1989. The thesis develops an understanding of the period as one entailing conditions of organ.le crisis. It attempts to show the PFP' s behaviour in the context of structural and conjunctural crises. The thesis periodises the Party's policy and strategic responses and makes an effort to show its contradictory nature. An effort is made to understand this contradictory character in terms of the party's class location with respect to the white dominating classes and leading elements within it; in relation to the black dominated classes; as well as in terms of the liberal tradition within which the Party operated. -

IFLA Journal Volume 41 Number 1 March 2015

IFLA Volume 41 Number 1 March 2015 IFLA Contents Editorial Promoting research that intersects with practice and advocacy 3 Steven W. Witt Articles Academic libraries: A soft analysis, a warning and the road ahead 5 James M. Matarazzo and Toby Pearlstein The expansion of the personal name authority record under Resource Description and Access: Current status and quality considerations 13 Heather Lea Moulaison Sharing science: The state of institutional repositories in Ghana 25 Jenny Bossaller and Kodjo Atiso The library in the research culture of the university: A case study of Victoria University Library 40 Ralph Kiel, Frances O’Neil, Adrian Gallagher and Cindy Mohammad The rural library’s role in Ugandan secondary students’ reading habits 53 Valeda F. Dent and Geoff Goodman Conservation of library collections: Research in library collections conservation and its practical application at the Scientific Library of Tomsk State University 63 Olga Manernova Scholarly productivity of Arab librarians in Library and Information Science journals from 1981 to 2010: An analytical study 70 Mahmoud Sherif Zakaria Abstracts 80 Aims and Scope IFLA Journal is an international journal publishing peer reviewed articles on library and information services and the social, political and economic issues that impact access to information through libraries. The Journal publishes research, case studies and essays that reflect the broad spectrum of the profession internationally. To submit an article to IFLA Journal please visit: http://ifl.sagepub.com IFLA Journal Official Journal of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions ISSN 0340-0352 [print] 1745-2651 [online] Published 4 times a year in March, June, October and December Editor Steve Witt, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 321 Main Library, MC – 522 1408 W.