By Anna Lefatshe Moagi Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER of ARTS in the Subject POLITICS A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Address List of South Africans Banned and Banished for Opposition to Apartheid and of Families of Political Prisoners

Address List of South Africans Banned and Banished for Opposition to Apartheid and of Families of Political Prisoners http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1971_45 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Address List of South Africans Banned and Banished for Opposition to Apartheid and of Families of Political Prisoners Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 48/71 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Contributor Anti-Apartheid Movement Publisher Department of Political and Security Council Affairs Date 1971-11-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, United Kingdom Coverage (temporal) 1971 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Contains a list of addresses provided by the Anti-Apartheid Movement. -

CULL0001-2-32-01-Jpeg.Pdf

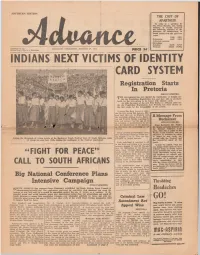

SOUTHERN EDITION THE COST OF APARTHEID In reply to a question by Mr. Brian Bunting, the Acting Minister of Health disclosed the following Statistics of the incidence of tuberculosis in South Africa over the past four years: 1948 1952 Europeans 1,609 1,422 Coloured persons (including w d v a a c e Asiatics) 5,478 5,715 Africans 15,681 20,942 Registered at tbe ADVANCE, THURSDAY, AUGUST 27, 1953 G eneral Past* Cfilce as a Newspaper PRICE 3d INDIANS NEXT VICTIMS OF IDENTITY CARD SYSTEM Registration Starts In Pretoria JOHANNESBURG. rpH E Government has now started the registration of Indians un- der the Population Registration Act, and they will, in all likeli hood, be the next group to be issued with identity cards. As with the issue of the new Pass Books to Africans (also un der the Population Registration Act) Pretoria has been chosen as the first centre for the inauguration of the system. A notice has been issued to Asia tics (in this group fall Indians, Chi nese and Malays) in Pretoria and the townships of East Lynne, Silver- A Message From ton and Pretoria North, requiring all Bucharest men and women over the age of 16 to complete a questionnaire to en JOHANNESBURG. able the Department of the Interior From Bucharest Mr. Walter to determine the citizenship oc all M. Sisulu, secretary-general of Asiatics. the African National Con gress, who was a guest of the These printed questionnaire forms World Youth Festival, sent an were distributed house to house dur interview to Advance in which ing August 12 to 21. -

The Influence of the Global Financial Crisis and Other Challenges for South Africa's Non- Governmental Organisations and the Prospects for Deepening Democracy

The Influence of the Global Financial Crisis and other Challenges for South Africa's Non- Governmental Organisations and the Prospects for Deepening Democracy By Nomathamsanqa Masiko Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in (International Studies)in the Faculty of Arts and Social Science at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Nicola de Jager March 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. November 2012 Copyright © 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT The point of departure for this study was the wide-ranging furore in media publications regarding the pervasive decline in donor funding for civil society organisations in South Africa, as influenced by the recent global financial crisis, and the subsequent shutting down of a number of civil society organisations. The decision to embark on this study has its roots in the fact that civil society is an important feature in a democracy with regards to government responsiveness, accountability as well as citizen participation in democratic governance. In South Africa, particularly, this is important in light of the country’s fledgling democracy, and even more so, when considering the ruling party’s overwhelming political power resulting in a dominant party system. -

Faces of Africa: Diversity and Progress; Repression and Struggle, Report of Special Study Missions to Africa

Faces of Africa: Diversity and Progress; Repression and Struggle, Report of Special Study Missions to Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.uscg006 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Faces of Africa: Diversity and Progress; Repression and Struggle, Report of Special Study Missions to Africa Alternative title Report of Special Study Missions to Africa Author/Creator Special Study Mission; Committee on Foreign Affairs; House of Representatives Publisher U.S. Government Printing Office Date 1972-09-21 Resource type Hearings Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Africa (region), United States, South Africa, Zambia, Botswana, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde Coverage (temporal) 1971 - 1972 Source Congressional Hearings and Mission Reports: U.S. -

Tuesday, 5 May 2015

05 MAY 2015 PAGE: 1 of 45 TUESDAY, 5 MAY 2015 ____ PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF PROVINCES ____ The Council met at 14:01. The Deputy Chairperson (Mr R J Tau) took the Chair and requested members to observe a moment of silence for prayers or meditation. ANNOUNCEMENTS, TABLINGS AND COMMITTEE REPORTS – see col 000. NOTICES OF MOTION Ms E C VAN LINGEN: Deputy Chairperson, I hereby give notice that on the next sitting day of the Council, I shall move on behalf of the DA: That this House has a snap debate on the effective functioning of the National Council of Provinces as prescribed in the Constitution, because — (a) the administration and effective functioning of the House are falling apart; 05 MAY 2015 PAGE: 2 of 45 (b) the last official programme approved by the Whippery and agreed to in the Programming Committee is dated 18 March; (c) programmes and schedules are changed by the presiding officers at will without the consent or participation of the Whippery and the Programming Committee; (d) the Rules of the NCOP have not been approved; (e) the presiding officers and the secretary of this Chamber do not respond to letters addressed to them specifically; (f) the subcommittee for finance should be elected to ensure that the finances of this Council are managed transparently; and (g) questions are raised about the due process followed in the appointment of the ad hoc committee on xenophobia. The DA calls for an urgent snap debate to address the issues raised above and to bring the NCOP back to its constitutional mandate. -

GSSA Johannesburg Branch, Book List

GSSA Johannesburg Branch, Book List Author Title Adam, Frank The Clans, Septs and Regiments of the Scottish Highlands Adams, J Atlas of American History Albertyn, A P J Ensiklopedie van (Plaas) Name in Suid Wes Afrika Barnes, Pamela M Through the Chequered Path: William Howard's Party of 1820 Settlers Bloore, John Computer Programs for the Family Historian. Bond, John They Were South Africans Breed, Geoffrey R My Ancestors were Baptists Brownell, F British Immigration, 1946-1970 Bull, Esmé Aided Immigration from Britain to South Africa 1857-1867 Camp, Anthony J My Ancestor was a Migrant Chambers, W R Chambers Biographical Dictionary Cloete, Anna Orlandini, 'n Familiegeskiedenis Coertzen, Pieter The Huguenots of South Africa 1688-1988 (2 copies) Cox, Jane Wills, Inventories and Death Duties Currer-Briggs, Noel Worldwide Family History Currer-Briggs & Gambier Debrett's Guide to Tracing your Ancestry de Beer, D & J Die de Beer-Familie – Drie Eeue in Suid Afrika de Bruyn G F C Geslagsregister De Bruijn Dickason, Graham Irish Settlers in the Cape Dickason, Graham The Dickason Family in South Africa Dickason, Graham Cornish Immigrants to South Africa Doane Searching for your Ancestors Dorling, H. Taprell Service Medals, Ribbons, Badges and Flags Ducat, K E Smith: John Baird and his Family Ducat, K E Ducat, Chronicles of a Family Emery, Ashton A-Z of British Genealogical Research FitzHugh, Terrick V.H The Dictionary of Genealogy Fowler, Simon Sources for Labor History Fox-Davis A Complete Guide to Heraldry Gaines, H The Futler Family Grastrow, Shelagh Who's Who in South African Politics No. 1 Grastrow, Shelagh Who's Who in South African Politics No. -

The Barometer of Social Trends M E M B E R S

THE BAROMETER OF SOCIAL TRENDS M E M B E R S MAJOR DONORS Anglo American & De Beers Chairman's Fund Education Trust First National Bank of Southern Africa Ltd Human Sciences Research Council South African Breweries Ltd AECI Ltd * Africa Institute of SA * Amalgamated Beverage Industries * Barlow Limited * BP Southern Africa * Chamber of Mines of SA * Colgate-Palmolive (Pty) Ltd * Data Research Africa * Durban Regional Chamber of Business * ESKOM * Gencor SA Limited * Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Co Ltd * Johnson & Johnson * S. C. Johnson Wax * Konrad Adenauer Stiftung * KwaZulu Finance & Investment Corp * Liberty Life * Malbak Ltd * Nampak * Pick 'n Pay Corporate Services * Pretoria Portland Cement Co * Rand Merchant Bank * Richards Bay Minerals * Sanlam * SA Sugar Association * Southern Life * Standard Bank Foundation * Starcke Associates * Suncrush Limited * University of South Africa (UNISA) * Vaal Reef Exploration & Mining Co Ltd * Wooltru Ltd INDICATOSOUTH AFRICRA ! L-0 LIFE SOUTHERN LIFE Life tends to be two steps forward, three steps back. To keep you going forwards, Southern Life is geared to helping you manage your future better. Our wide range of inflation-beating investment opportunities, coupled with R30 billion SOUTHERN in managed assets, is guided by more than a century of financial management Together, we can do more advice. We can help you cut a clear path to success. to manage your future better SUMMER 1995 EDITORIAL Journalists are an excitable and over stretched group prone - INDICATOR SOUTH AFRICA by nature or through training - to instant judgements, drama and errors in their endless, time pressured search for new and interesting 'angles' for their articles. I know this about Quarterly Report VOLUME 13 NUMBER 1 journalists, because I am one. -

“South Africa's 800” by Henry Katzew

SOUTH AFRICA’S 800 The Story of South African Volunteers in Israel’s War of Birth by Henry Katzew Compiled and produced by Maurice and Marcia Ostroff from Henry Katzew’s original manuscript Edited by Joe Woolf Key to the Front Cover Top to bottom: • The famous Haganah immigrant ship S.S Exodus 1947, in which 4500 refugees were forcibly returned to Hamburg in September 1947. (See foreword & Palestine Post article page 23) • Boris Senior in a Spitfire constructed from bits and pieces. • A group of Machalniks, in the Tank Corps. • A column of the 9th Palmach, Commando Battalion. Revised and reprinted November 2003 COPYRIGHT© All rights reserved No part of this document may be reproduced by any means whatsoever, except with the prior express written permission of the South African Zionist Federation. Correspondence should be addressed to: Telfed, 19/1 Schwartz Street, Ra’anana, 43212 Israel Telephone +972 9-7446110 Fax + 972 9-7446112 E-mail: [email protected] About this book “South Africa’s 800” is about Machal, the collective Hebrew acronym for volunteers from abroad and about individual volunteers, colloquially known as Machalniks. The book reveals details never previously documented and provides a valuable new perspective on Israel’s birth and struggle for survival. It includes eye witness reports by active participants in the events. While written mainly through South African eyes, the book also contains gripping anecdotes about volunteers from the USA, Britain and other countries. It throws new light on important events and personalities of the time. In his engaging eloquent style, Henry Katzew takes the reader on a fascinating expedition through recent historical events including: • Adventures of 8 young South Africans in their ill-fated attempt to bypass British restrictions on immigration to Palestine, by travelling overland from Pretoria. -

South Africa's Founding Democratic Election 1994

SOUTH AFRICA’S FOUNDING DEMOCRATIC ELECTION 1994 AFRICA’S FOUNDING DEMOCRATIC SOUTH EISA Bibliographical Series No 1: South Africa’s Second Democratic Election 1999; An Annotated Bibliography Compiled by Beth Strachan, 2001 SOUTH AFRICA’S FOUNDING DEMOCRATIC ELECTION 1994 A Select and Annotated Bibliography ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ STRACHAN ISBN 1-920095-33-0 ▲ compiled by ▲ BETH STRACHAN 9781920 095338 Order from: [email protected] EISA BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SERIES NO 2 EISA BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SERIES NO 2 i SOUTH AFRICA’S FOUNDING DEMOCRATIC ELECTION 1994 A Select and Annotated Bibliography compiled by BETH STRACHAN 2005 EISA BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SERIES NO 2 ii EISA BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SERIES NO 2 Published by EISA 2nd Floor, The Atrium 41 Stanley Avenue, Auckland Park Johannesburg, South Africa 2006 P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: 27 11 482 5495 Fax: 27 11 482 6163 Email: [email protected] www.eisa.org.za ISBN: 1-920095-33-0 EISA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of EISA. First published 2005 EISA is a non-partisan organisation which seeks to promote democratic principles, free and fair elections, a strong civil society and good governance at all levels of Southern African society. –––––––––––– ❑ –––––––––––– Cover photograph: Yoruba Beaded Crown Reproduced with the kind permission of Hamill Gallery of African Art, Boston, Ma USA EISA Bibliographical Series No 2 EISA BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SERIES NO 2 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iv List of Acronyms vii Map xiv Bibliograpy Author INdex Subject Index . -

The Ramaphosa Case Study

THE RAMAPHOSA CASE STUDY ‘Many shades of the truth’: THE RAMAPHOSA CASE STUDY by Nobayethi Dube 1 ‘Many shades of the truth’: THE RAMAPHOSA CASE STUDY by Nobayethi Dube Part I: Executive summary .............................................................1 Part II: Introduction .........................................................................3 Terms of Reference ...............................................................................................................................4 Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................5 Structure of this report ........................................................................................................................6 Overview ..................................................................................................................................................7 Part III: Versions of truth .................................................................7 The affected ..........................................................................................................................................13 Community organising .....................................................................................................................18 Social cohesion ...................................................................................................................................18 Cross-cutting issues ............................................................................................................................19 -

IDAFSA Canada

IDAFSA Canada Legal defence and aid for the victims of apartheid 294 Albert Street Suite 200 Ottawa, Ontario KIP 6E6 Tel: (613) 233-5939 Envoy: IDAFSA Telex: AHH 6740 FAX: (613) 233-6228 Mission Statement o f IDAFSA (Canada) o assist those who are the victims of apartheid by ensuring Ttheir legal defence, by providing humanitarian aid and by building support in Canada through representation and education. IDAFSA (Canada)'s Objectives are to: 1 Ensure legal and financial assistance to prisoners who are detained under the apartheid laws and practices in South Africa, and to their families. 2 Educate Canadians about the reality of life under apartheid. Origins DAFSA's origins date back over 30 years to South Africa, J when legal and financial aid was provided in the famous trial involving Nelson Mandela and Albert Luthuli. For supporting the opponents of apartheid, the IDAFSA's oper ations through its South African committees were banned in 1966. Since then all the organizational work has been done externally, with a head office in London, England and affiliated national committees in several countries. In 1974, a North American Committee was established. In 1980, Andrew Brewin, a retired lawyer and long time Member of Parliament, together with several IDAFSA supporters, started an independent committee in Canada, affiliated to the international organization. IDAFSA (Canada) is federally incor porated as a non- profit corporation and registered as a charity with Revenue Canada. The money IDAFSA (Canada) raises for its humanitarian work, is generously matched by the Canadian government. Creating Awareness DAFSA (Canada) is committed to helping you to find out the J reality of life under apartheid and to give you the opportu nity to do something about it. -

07 October 2014

ARMS PROCUREMENT COMMISSION Transparency, Accountability and the Rule of Law PUBLIC HEARINGS PHASE 2 DATE : 07 OCTOBER 2014 (PAGE 8284 – 8399) APC 8284 PUBLIC HEARINGS 7 OCTOBER 2014 PHASE 1 CHAIRPERSON: Good morning. I think yesterday when we adjourned we said that this morning we will deal with the question of the document which MR CRAWFORD BROWNE wanted to refer to and I think there was documentation from fellow staff and they promised that today they 5 will come [indistinct] to deal with the admissibility or otherwise that document. I think in the previous sittings this issue was [indistinct] and I think that I should mention that it is clear from the transcripts, I did make a ruling that that document is not admissible. During argument Mr 10 Hoffman appeared on behalf of MR CRAWFORD BROWNE when cross-examining one of the witnesses, wanted to use that document and there was a feeling that that document might not be admissible at that stage. If you look at the transcript, I think page 7570 Mr 15 Hoffman said the following: “Mr Commissioner, my instructions are that this document is in the public domain and there was indeed [indistinct]. The document was brought into existence in order to clean up the image of [indistinct] so that they could do business in the United States. 20 [indistinct] with anybody and I have had a personal conversation with the relevant official asking about it and the answer was you can have it and we will give you anything else that you need.” That is what advocate Hoffman has said according to this transcript.