Quadrilateral Mesh Generation III : Optimizing Singularity Configuration Based on Abel-Jacobi Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Dual Configurations and Regular Graphs

SELF-DUAL CONFIGURATIONS AND REGULAR GRAPHS H. S. M. COXETER 1. Introduction. A configuration (mci ni) is a set of m points and n lines in a plane, with d of the points on each line and c of the lines through each point; thus cm = dn. Those permutations which pre serve incidences form a group, "the group of the configuration." If m — n, and consequently c = d, the group may include not only sym metries which permute the points among themselves but also reci procities which interchange points and lines in accordance with the principle of duality. The configuration is then "self-dual," and its symbol («<*, n<j) is conveniently abbreviated to na. We shall use the same symbol for the analogous concept of a configuration in three dimensions, consisting of n points lying by d's in n planes, d through each point. With any configuration we can associate a diagram called the Menger graph [13, p. 28],x in which the points are represented by dots or "nodes," two of which are joined by an arc or "branch" when ever the corresponding two points are on a line of the configuration. Unfortunately, however, it often happens that two different con figurations have the same Menger graph. The present address is concerned with another kind of diagram, which represents the con figuration uniquely. In this Levi graph [32, p. 5], we represent the points and lines (or planes) of the configuration by dots of two colors, say "red nodes" and "blue nodes," with the rule that two nodes differently colored are joined whenever the corresponding elements of the configuration are incident. -

15 BASIC PROPERTIES of CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨Urgenrichter-Gebert, and G¨Unterm

15 BASIC PROPERTIES OF CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨urgenRichter-Gebert, and G¨unterM. Ziegler INTRODUCTION Convex polytopes are fundamental geometric objects that have been investigated since antiquity. The beauty of their theory is nowadays complemented by their im- portance for many other mathematical subjects, ranging from integration theory, algebraic topology, and algebraic geometry to linear and combinatorial optimiza- tion. In this chapter we try to give a short introduction, provide a sketch of \what polytopes look like" and \how they behave," with many explicit examples, and briefly state some main results (where further details are given in subsequent chap- ters of this Handbook). We concentrate on two main topics: • Combinatorial properties: faces (vertices, edges, . , facets) of polytopes and their relations, with special treatments of the classes of low-dimensional poly- topes and of polytopes \with few vertices;" • Geometric properties: volume and surface area, mixed volumes, and quer- massintegrals, including explicit formulas for the cases of the regular simplices, cubes, and cross-polytopes. We refer to Gr¨unbaum [Gr¨u67]for a comprehensive view of polytope theory, and to Ziegler [Zie95] respectively to Gruber [Gru07] and Schneider [Sch14] for detailed treatments of the combinatorial and of the convex geometric aspects of polytope theory. 15.1 COMBINATORIAL STRUCTURE GLOSSARY d V-polytope: The convex hull of a finite set X = fx1; : : : ; xng of points in R , n n X i X P = conv(X) := λix λ1; : : : ; λn ≥ 0; λi = 1 : i=1 i=1 H-polytope: The solution set of a finite system of linear inequalities, d T P = P (A; b) := x 2 R j ai x ≤ bi for 1 ≤ i ≤ m ; with the extra condition that the set of solutions is bounded, that is, such that m×d there is a constant N such that jjxjj ≤ N holds for all x 2 P . -

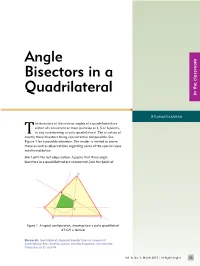

Angle Bisectors in a Quadrilateral Are Concurrent

Angle Bisectors in a Quadrilateral in the classroom A Ramachandran he bisectors of the interior angles of a quadrilateral are either all concurrent or meet pairwise at 4, 5 or 6 points, in any case forming a cyclic quadrilateral. The situation of exactly three bisectors being concurrent is not possible. See Figure 1 for a possible situation. The reader is invited to prove these as well as observations regarding some of the special cases mentioned below. Start with the last observation. Assume that three angle bisectors in a quadrilateral are concurrent. Join the point of T D E H A F G B C Figure 1. A typical configuration, showing how a cyclic quadrilateral is formed Keywords: Quadrilateral, diagonal, angular bisector, tangential quadrilateral, kite, rhombus, square, isosceles trapezium, non-isosceles trapezium, cyclic, incircle 33 At Right Angles | Vol. 4, No. 1, March 2015 Vol. 4, No. 1, March 2015 | At Right Angles 33 D A D A D D E G A A F H G I H F F G E H B C E Figure 3. If is a parallelogram, then is a B C B C rectangle B C Figure 2. A tangential quadrilateral Figure 6. The case when is a non-isosceles trapezium: the result is that is a cyclic Figure 7. The case when has but A D quadrilateral in which : the result is that is an isosceles ∘ trapezium ( and ∠ ) E ∠ ∠ ∠ ∠ concurrence to the fourth vertex. Prove that this line indeed bisects the angle at the fourth vertex. F H Tangential quadrilateral A quadrilateral in which all the four angle bisectors G meet at a pointincircle is a — one which has an circle touching all the four sides. -

Scribability Problems for Polytopes

SCRIBABILITY PROBLEMS FOR POLYTOPES HAO CHEN AND ARNAU PADROL Abstract. In this paper we study various scribability problems for polytopes. We begin with the classical k-scribability problem proposed by Steiner and generalized by Schulte, which asks about the existence of d-polytopes that cannot be realized with all k-faces tangent to a sphere. We answer this problem for stacked and cyclic polytopes for all values of d and k. We then continue with the weak scribability problem proposed by Gr¨unbaum and Shephard, for which we complete the work of Schulte by presenting non weakly circumscribable 3-polytopes. Finally, we propose new (i; j)-scribability problems, in a strong and a weak version, which generalize the classical ones. They ask about the existence of d-polytopes that can not be realized with all their i-faces \avoiding" the sphere and all their j-faces \cutting" the sphere. We provide such examples for all the cases where j − i ≤ d − 3. Contents 1. Introduction 2 1.1. k-scribability 2 1.2. (i; j)-scribability 3 Acknowledgements 4 2. Lorentzian view of polytopes 4 2.1. Convex polyhedral cones in Lorentzian space 4 2.2. Spherical, Euclidean and hyperbolic polytopes 5 3. Definitions and properties 6 3.1. Strong k-scribability 6 3.2. Weak k-scribability 7 3.3. Strong and weak (i; j)-scribability 9 3.4. Properties of (i; j)-scribability 9 4. Weak scribability 10 4.1. Weak k-scribability 10 4.2. Weak (i; j)-scribability 13 5. Stacked polytopes 13 5.1. Circumscribability 14 5.2. -

Unilateral and Equitransitive Tilings by Equilateral Triangles

Discrete Mathematics 340 (2017) 1669–1680 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Discrete Mathematics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/disc Unilateral and equitransitive tilings by equilateral trianglesI Rebekah Aduddell a, Morgan Ascanio b, Adam Deaton c, Casey Mann b,* a Texas Lutheran University, United States b University of Washington Bothell, United States c University of Texas, United States article info a b s t r a c t Article history: A tiling of the plane by polygons is unilateral if each edge of the tiling is a side of at most Received 6 July 2016 one polygon of the tiling. A tiling is equitransitive if for any two congruent tiles in the tiling, Received in revised form 18 October 2016 there exists a symmetry of the tiling mapping one to the other. It is known that a unilateral Accepted 31 October 2016 and equitransitive (UE) tiling can be made with any finite number of congruence classes of Available online 16 December 2016 squares. This article addresses the related question, raised in the book Tilings and Patterns by Keywords: Grünbaum and Shephard, of finding all UE tilings by equilateral triangles. In particular, we Tiling show that there are only two classes of UE tilings admitted by a finite number of congruence Triangles classes of equilateral triangles: one with two sizes of triangles and one with three sizes of Unilateral triangles. Equitransitive ' 2016 Published by Elsevier B.V. 1. Introduction A plane tiling T is a countable set of closed topological disks, fT1; T2; T3;:::g, that covers the plane without overlaps (i.e. -

Computing Triangulations Using Oriented Matroids

Takustraße 7 Konrad-Zuse-Zentrum D-14195 Berlin-Dahlem fur¨ Informationstechnik Berlin Germany JULIAN PFEIFLE AND JORG¨ RAMBAU Computing Triangulations Using Oriented Matroids ZIB-Report 02-02 (January 2002) COMPUTING TRIANGULATIONS USING ORIENTED MATROIDS JULIAN PFEIFLE AND JORG¨ RAMBAU ABSTRACT. Oriented matroids are combinatorial structures that encode the combinatorics of point configurations. The set of all triangulations of a point configuration depends only on its oriented matroid. We survey the most important ingredients necessary to exploit ori- ented matroids as a data structure for computing all triangulations of a point configuration, and report on experience with an implementation of these concepts in the software package TOPCOM. Next, we briefly overview the construction and an application of the secondary polytope of a point configuration, and calculate some examples illustrating how our tools were integrated into the POLYMAKE framework. 1. INTRODUCTION This paper surveys efficient combinatorial methods to compute triangulations of point configurations. We present results obtained for the first time by a software implementation (TOPCOM [Ram99]) of these ideas. It turns out that a subset of all triangulations of a point configuration has a structure useful in different areas of mathematics, and we highlight one particular instance of such a connection. Finally, we calculate some examples by integrating TOPCOM into the POLYMAKE [GJ01] framework. Let us begin by motivating the use of triangulations and providing a precise definition. 1.1. Why triangulations? Triangulations are widely used as a standard tool to decom- pose complicated objects into simple objects. A solution to a problem on a complicated object can sometimes be found by gluing solutions on the simple objects. -

Spaces of Polygons in the Plane and Morse Theory

Swarthmore College Works Mathematics & Statistics Faculty Works Mathematics & Statistics 4-1-2005 Spaces Of Polygons In The Plane And Morse Theory Don H. Shimamoto Swarthmore College, [email protected] C. Vanderwaart Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-math-stat Part of the Mathematics Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Don H. Shimamoto and C. Vanderwaart. (2005). "Spaces Of Polygons In The Plane And Morse Theory". American Mathematical Monthly. Volume 112, Issue 4. 289-310. DOI: 10.2307/30037466 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-math-stat/30 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics & Statistics Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spaces of Polygons in the Plane and Morse Theory Author(s): Don Shimamoto and Catherine Vanderwaart Source: The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 112, No. 4 (Apr., 2005), pp. 289-310 Published by: Mathematical Association of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30037466 Accessed: 19-10-2016 15:46 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Mathematical Association of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Mathematical Monthly This content downloaded from 130.58.65.20 on Wed, 19 Oct 2016 15:46:08 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Spaces of Polygons in the Plane and Morse Theory Don Shimamoto and Catherine Vanderwaart 1. -

Radiation View Factors

RADIATIVE VIEW FACTORS View factor definition ................................................................................................................................... 2 View factor algebra ................................................................................................................................... 3 View factors with two-dimensional objects .............................................................................................. 4 Very-long triangular enclosure ............................................................................................................. 5 The crossed string method .................................................................................................................... 7 View factor with an infinitesimal surface: the unit-sphere and the hemicube methods ........................... 8 With spheres .................................................................................................................................................. 9 Patch to a sphere ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Frontal ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Level...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Tilted .................................................................................................................................................... -

MYSTERIES of the EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE, First Published 2010

MYSTERIES OF THE EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE Brian J. McCartin Applied Mathematics Kettering University HIKARI LT D HIKARI LTD Hikari Ltd is a publisher of international scientific journals and books. www.m-hikari.com Brian J. McCartin, MYSTERIES OF THE EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE, First published 2010. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the publisher Hikari Ltd. ISBN 978-954-91999-5-6 Copyright c 2010 by Brian J. McCartin Typeset using LATEX. Mathematics Subject Classification: 00A08, 00A09, 00A69, 01A05, 01A70, 51M04, 97U40 Keywords: equilateral triangle, history of mathematics, mathematical bi- ography, recreational mathematics, mathematics competitions, applied math- ematics Published by Hikari Ltd Dedicated to our beloved Beta Katzenteufel for completing our equilateral triangle. Euclid and the Equilateral Triangle (Elements: Book I, Proposition 1) Preface v PREFACE Welcome to Mysteries of the Equilateral Triangle (MOTET), my collection of equilateral triangular arcana. While at first sight this might seem an id- iosyncratic choice of subject matter for such a detailed and elaborate study, a moment’s reflection reveals the worthiness of its selection. Human beings, “being as they be”, tend to take for granted some of their greatest discoveries (witness the wheel, fire, language, music,...). In Mathe- matics, the once flourishing topic of Triangle Geometry has turned fallow and fallen out of vogue (although Phil Davis offers us hope that it may be resusci- tated by The Computer [70]). A regrettable casualty of this general decline in prominence has been the Equilateral Triangle. Yet, the facts remain that Mathematics resides at the very core of human civilization, Geometry lies at the structural heart of Mathematics and the Equilateral Triangle provides one of the marble pillars of Geometry. -

Configuration Spaces of Plane Polygons and a Sub-Riemannian

Configuration spaces of plane polygons and a sub-Riemannian approach to the equitangent problem Jes´usJer´onimo-Castro∗ and Serge Tabachnikovy July 1, 2018 1 Introduction Given a strictly convex plane curve γ and a point x in its exterior, there are two tangent segments to γ from x. The equitangent locus of γ is the set of points x for which the two tangent segments have equal lengths. An equi- tangent n-gon of γ is a circumscribed n-gon such that the tangent segments to γ from the vertices have equal lengths, see Figure 1. For example, if γ is a circle, the equitangent locus is the whole exterior of γ (this property is characteristic of circles [20]), and if γ is an ellipse then its equitangent locus consists of the two axes of symmetry (this implies that an ellipse does not admit equitangent n-gons with n 6= 4). Generically, the equitangent locus of a curve γ is also a curve, say, Γ. Note that Γ is not empty; in fact, every curve γ has pairs of equal tangent segments of an arbitrary length. The equitangent problem is to study the arXiv:1408.3747v1 [math.DG] 16 Aug 2014 relation between a curve and its equitangent locus. For example, if the equitangent locus contains a line tangent to γ, then γ must be a circle. On the other hand, there exists an infinite-dimensional, ∗Facultad de Ingenier´ıa,Universidad Aut´onomade Quer´etaro,Cerro de las Campanas s/n, C. P. 76010, Quer´etaro,M´exico;[email protected] yDepartment of Mathematics, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA, and ICERM, ICERM, Brown University, Box 1995, Providence, RI 02912, USA; [email protected] 1 A3 A2 B2 B1 A 1 Figure 1: An equitangent pentagon: jA2B1j = jA2B2j, and likewise, cycli- cally. -

Configuration Spaces of Convex and Embedded Polygons in the Plane

Swarthmore College Works Mathematics & Statistics Faculty Works Mathematics & Statistics 10-1-2014 Configuration Spaces Of Convex And Embedded Polygons In The Plane Don H. Shimamoto Swarthmore College, [email protected] Mary K. Wootters , '08 Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-math-stat Part of the Mathematics Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Don H. Shimamoto and Mary K. Wootters , '08. (2014). "Configuration Spaces Of Convex And Embedded Polygons In The Plane". Geometriae Dedicata. Volume 172, Issue 1. 121-134. DOI: 10.1007/ s10711-013-9910-x https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-math-stat/82 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics & Statistics Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Configuration spaces of convex and embedded polygons in the plane Don Shimamoto∗ and Mary Woottersy A celebrated result of Connelly, Demaine, and Rote [6] states that any poly- gon in the plane can be \convexified.” That is, the polygon can be deformed in a continuous manner until it becomes convex, all the while preserving the lengths of the sides and without allowing the sides to intersect one another. In the language of topology, their argument shows that the configuration space of embedded polygons with prescribed side lengths deformation retracts onto the configuration space of convex polygons having those side lengths. In particular, both configuration spaces have the same homotopy type. Connelly, Demaine, and Rote observe (without proof) that the space of convex configurations is con- tractible. -

18 SYMMETRY of POLYTOPES and POLYHEDRA Egon Schulte

18 SYMMETRY OF POLYTOPES AND POLYHEDRA Egon Schulte INTRODUCTION Symmetry of geometric figures is among the most frequently recurring themes in science. The present chapter discusses symmetry of discrete geometric structures, namely of polytopes, polyhedra, and related polytope-like figures. These structures have an outstanding history of study unmatched by almost any other geometric object. The most prominent symmetric figures, the regular solids, occur from very early times and are attributed to Plato (427-347 b.c.e.). Since then, many changes in point of view have occurred about these figures and their symmetry. With the arrival of group theory in the 19th century, many of the early approaches were consolidated and the foundations were laid for a more rigorous development of the theory. In this vein, Schl¨afli (1814-1895) extended the concept of regular polytopes and tessellations to higher dimensional spaces and explored their symmetry groups as reflection groups. Today we owe much of our present understanding of symmetry in geometric figures (in a broad sense) to the influential work of Coxeter, which provided a unified approach to regularity of figures based on a powerful interplay of geometry and algebra [Cox73]. Coxeter’s work also greatly influenced modern developments in this area, which received a further impetus from work by Gr¨unbaum and Danzer [Gr¨u77a,DS82]. In the past 20 years, the study of regular figures has been extended in several directions that are all centered around an abstract combinatorial polytope theory and a combinatorial notion of regularity [McS02]. History teaches us that the subject has shown an enormous potential for revival.