The Impact of Race Upon Legislators' Policy Preferences and Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexikon Politik Улс Төрийн Тайлбар Толь

Lexikon Politik Улс төрийн тайлбар толь Lexikon Politik Улс төрийн тайлбар толь Энэхүү тайлбар толийг Монсудар хэвлэлийн газрын санаачлагаар Монгол дахь Конрад-Аденауэр-Сангийн дэмжлэгтэйгээр орчуулан хүргэв. ДАА ННА У Lexikon Politik Улс төрийн тайлбар толь Төслийн зохицуулагч Б.Оюундарь Орчуулагч Б.Ганхөлөг, Б.Энхтөгс, Б.Эрдэнэчимэг, Д.Үүрцайх, О.Цэрэнчимэд, У.Отгонбаяр, О.Ариунаа, Ц.Уянга, М.Сэргэлэн (Монгол-Германы гүүр төрийн бус байгууллагын баг) Орчуулгын редактор О.Цэрэнчимэд (Удирдлагын академийн Бодлого, Улс төр судлалын тэнхимийн эрхлэгч, дэд профессор) Д.Үүрцайх (ХБНГУ-ын Бонн хотын их сургууль, хууль зүйн ухааны магистр) Ц.Уянга (ХБНГУ-ын Льюдвиг Максимиллианы Их Сургуулийн Улс төрийн шинжлэх ухааны магистр, Австралийн Мельбурний Их Сургуулийн хөдөлмөрийн эрх зүйн магистр) Редакторууд Б.Батбаатар, Д.Очирмаа Монгол орчуулгын эрх © 2019 Монсудар хэвлэлийн газар RECLAMS UNIVERSAL-BIBILIOTHEK Nr. 18714 2009 Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co. KG, Siemensstraße 32, 71254 Ditzingen. Тус бүтээлийн орчуулгыг Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Mongolei ивээн тэтгэсэн болно. ISBN Бүх эрх хуулиар хамгаалагдсан болно.Энэхүү номын эхийг хэвлэлийн газрын зөвшөөрөлгүйгээр хэсэгчлэн болон бүтнээр нь дахин хэвлэх,хайлтын системд байршуулах, цахим,механик,фото хуулбар зэрэг ямар ч хэлбэрээр хувилж олшруулах,түгээн тараахыг хатуу хориглоно. Агуулга Удиртгал . 9 Abgeordnete – Парламентын гишүүн . 17 Außenpolitik – Гадаад бодлого . 20 Autoritäres Regime – Авторитар дэглэм . .24 Bürgertugenden – Иргэний ухамсарт үйл . 28 Deliberative Demokratie – Зөвлөлдөх ардчилал . 33 Demokratie – Ардчилал . 37 Demokratisierung/ Demokratisierungswellen – Ардчиллын давлагаа . 43 Diktatur – Диктатур . 48 Diskurs – Дискурс . 51 Elektronische Demokratie – Цахим ардчилал . .55 Eliten – Элитүүд . .59 Europäische Union – Европын Холбоо . 64 Extremismus – Экстремизм . 69 Faschismus – Фашизм . 72 Feminismus – Феминизм . 76 Föderalismus – Федерализм . .80 Freiheit – Эрх чөлөө . 84 Gemeinwohl – Нийтийн сайн сайхан . .89 Gerechtigkeit – Шударга ёс . -

The Graduation Exercises Will Be Official

TheMONDAY, Graduation MAY THE EIGHTEENTH Exercises TWO THOUSAND AND FIFTEEN NINE O’CLOCK IN THE MORNING THOMAS K. HEARN, JR. PLAZA THE CARILLON: “Mediation from Thaïs” . Jules Massenet Raymond Ebert (’60), University Carillonneur William Stuart Donovan (’15), Student Carillonneur THE PROCESSIONAL . Led by Head Faculty Marshals THE OPENING OF COMMENCEMENT . Nathan O . Hatch President THE PRAYER OF INVOCATION . The Reverend Timothy L . Auman University Chaplain REMARKS TO THE GRADUATES . President Hatch THE CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES . Rogan T . Kersh Provost Carlos Brito, Doctor of Laws Sponsor: Charles L . Iacovou, Dean, School of Business Stephen T . Colbert, Doctor of Humane Letters Sponsor: Michele K . Gillespie, Dean-Designate, Wake Forest College George E . Thibault, Doctor of Science Sponsor: Peter R . Lichstein, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine Jonathan L . Walton, Doctor of Divinity Sponsor: Gail R . O'Day, Dean, School of Divinity COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS . Stephen Colbert Comedian and Late Night Television Host THE HONORING OF RETIRING FACULTY FROM THE REYNOLDA CAMPUS Bobbie L . Collins, M .S .L .S ., Librarian Ronald V . Dimock, Jr ., Ph .D ., Thurman D. Kitchin Professor of Biology Jack D . Ferner, M .B .A ., Lecturer of Management J . Kendall Middaugh, II, Ph .D ., Associate Professor of Management James T . Powell, Ph .D ., Associate Professor of Classical Languages David P . Weinstein, Ph .D ., Professor of Politics and International Affairs FROM THE MEDICAL CENTER CAMPUS James D . Ball, M .D ., Professor Emeritus of Radiology William R . Brown, Ph .D ., Professor Emeritus of Radiology Frank S . Celestino, M .D ., Professor Emeritus of Family and Community Medicine Wesley Covitz, M .D ., Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics Robert L . -

Ohio Senate Journal

JOURNALS OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OHIO SENATE JOURNAL TUESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2011 22 SENATE JOURNAL, TUESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2011 FIFTH DAY Senate Chamber, Columbus, Ohio Tuesday, January 11, 2011, 1:30 p.m. The Senate met pursuant to adjournment. Prayer was offered by Father Michael Lumpe, St. Catharine's Church, Bexley, Ohio, followed by the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag. The journal of the last legislative day was read and approved. On the motion of Senator Faber the Senate advanced to the ninth Order of Business, Offering of Resolutions. OFFERING OF RESOLUTIONS Senator Faber offered the following resolution: S. R. No. 4-Senator Faber. Relative to the appointment of Peggy B. Lehner, to fill the vacancy in the membership of the Senate created by the resignation of Jon Husted of the 6th Senatorial District. WHEREAS, Section 11 of Article II, Ohio Constitution, provides for the filling of a vacancy in the Senate by appointment by the members of the Senate who are affiliated with the same political party as the person last elected to the seat which has become vacant; and WHEREAS, Jon Husted of the 6th Senatorial District has resigned as a member of the Senate effective January 9, 2011, thus creating a vacancy in the Senate; now therefore be it RESOLVED, By the members of the Senate who are affiliated with the Republican party, that Peggy B. Lehner (Republican), having the qualifications set forth in the Ohio Constitution and the laws of Ohio to be a member of the Senate from the 6th Senatorial District is hereby appointed, pursuant to Section 11 of Article II, Ohio Constitution, as a member of the Senate from the 6th Senatorial District, to fill the vacancy created by Jon Husted; and be it further RESOLVED, That a copy of this Resolution be spread upon the journal of the Senate together with the yeas and nays of the members of the Senate affiliated with the Republican party voting on the Resolution, and that the Clerk of the Senate shall certify the Resolution and the vote on its adoption to the Secretary of State. -

Political Reelism: a Rhetorical Criticism of Reflection and Interpretation in Political Films

POLITICAL REELISM: A RHETORICAL CRITICISM OF REFLECTION AND INTERPRETATION IN POLITICAL FILMS Jennifer Lee Walton A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2006 Committee: John J. Makay, Advisor Richard Gebhardt Graduate Faculty Representative John T. Warren Alberto Gonzalez ii ABSTRACT John J. Makay, Advisor The purpose of this study is to discuss how political campaigns and politicians have been depicted in films, and how the films function rhetorically through the use of core values. By interpreting real life, political films entertain us, perhaps satirically poking fun at familiar people and events. However, the filmmakers complete this form of entertainment through the careful integration of American values or through the absence of, or attack on those values. This study provides a rhetorical criticism of movies about national politics, with a primary focus on the value judgments, political consciousness and political implications surrounding the films Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), The Candidate (1972), The Contender (2000), Wag the Dog (1997), Power (1986), and Primary Colors (1998). iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank everyone who made this endeavor possible. First and foremost, I thank Doctor John J. Makay; my committee chair, for believing in me from the start, always encouraging me to do my best, and assuring me that I could do it. I could not have done it without you. I wish to thank my committee members, Doctors John Warren and Alberto Gonzalez, for all of your support and advice over the past months. -

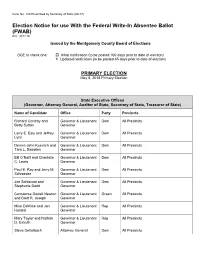

Election Notice for Use with the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C

Form No. 120 Prescribed by Secretary of State (09-17) Election Notice for use With the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C. 3511.16 Issued by the Montgomery County Board of Elections BOE to check one: Initial notification (to be posted 100 days prior to date of election) X Updated notification (to be posted 45 days prior to date of election) PRIMARY ELECTION May 8, 2018 Primary Election State Executive Offices (Governor, Attorney General, Auditor of State, Secretary of State, Treasurer of State) Name of Candidate Office Party Precincts Richard Cordray and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Betty Sutton Governor Larry E. Ealy and Jeffrey Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Lynn Governor Dennis John Kucinich and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Tara L. Samples Governor Bill O’Neill and Chantelle Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts C. Lewis Governor Paul E. Ray and Jerry M. Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Schroeder Governor Joe Schiavoni and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Stephanie Dodd Governor Constance Gadell-Newton Governor & Lieutenant Green All Precincts and Brett R. Joseph Governor Mike DeWine and Jon Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts Husted Governor Mary Taylor and Nathan Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts D. Estruth Governor Steve Dettelbach Attorney General Dem All Precincts Dave Yost Attorney General Rep All Precincts Zack Space Auditor of State Dem All Precincts Keith Faber Auditor of State Rep All Precincts Kathleen Clyde Secretary of State Dem All Precincts Frank LaRose Secretary of State Rep All Precincts Rob Richardson Treasurer of State Dem All Precincts Sandra O’Brien Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Robert Sprague Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Paul Curry (Write-In) Treasurer of State Green All Precincts U.S. -

(:I.FRK (;C COURT SUPREN1E COURT of OHIO

iN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF 01110 COLUMBUS, OHIO CASE NO: 2010 -0712 VALENTINE SCHUROWLIEW ANSWER TO RESPONDENTS' vs. MOTION TO DISMISS RELATOR'S COMPLAINT FOR A WRIT JUDGE LANCE MASON OF PROHIBITION r-^ r, and R JUDGE LAURA GALLAGHER (:i.FRK (;C COURT Respondents. SUPREN1E COURT OF OHIO RELATOR'S ANSWER TO RESPONllENTS' MOTION TO DISMISS RELA'TOR'S COMPLAINT FOR A WRIT OF PROHIBITION William Mason (0037540) (0025685) Stanley Josselson Cuyahoga County Prosecutor 1276 W. 3 St. #411 1200 Ontario St. 8°i Floor Cleveland, Oliio 44113 Cleveland, Ohio 44113 216-696-8070 216-443-7800 216-696-3752 fax Attorney for Respondents JosselsonL aw ffinail.com Attorney for Relator Certifrcate of Service 2010 to A copy of this Answer was sept by US mail on William Mason, Attorney forRespondents Judge Lau Galla er and Judge Lance Mason, Justice Center 1200 Ontario St. 8`h Floor Cleveland, Ohio, 44113. n rl{v( r'' Ci ? tliFJ CLEFJK OF CC7tJR1' SUPREME CtJUR7 OF OHIO TABLE OF CONTENTS . .. ... ..................................r, n, m TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................... ...................................................... ........... ..........1 INTRODUCTION ............................... ...._ ' ........................t STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................ .......................................7 LAW ANll ARGtTMENTS ..:...................................... ..........7 1. THE STANDARD FOR A WRIT OF PROHIBITION.......................................... II. THE PROBATE COURT HAS EXCLUSIVE JURISDICTION OVER THE ADMINISTRATION AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ESTATE OF SOFI.IA SCHUROWLIEW.INCLUDINGHERPRE-DEATIITRANSFERS .............................7 Pleas lacks subject matter jurisdiction A. The General Division of Common upon a decedent, negligence, breach of fiduciary duties over claims of fraud ..................... ...............:...................1 l owed a decedent, and conversion of a decedent's assets ... ...................... Pleas Court lacks jurisdiction over claims of B. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

April 5, 2017 Ohio State Capitol Columbus, Ohio

April 5, 2017 Ohio State Capitol Columbus, Ohio Richard Moore, Advocacy Chair Committee: Lauren Manson, David Kissinger, Ryan Clark, Jeff Haas, Mark Harvey, Grainne Mangan, Scott Mash, Lux Phatak, Kim Stults, Joanne White, Heidi Lamb , John Paganini, Giuseppe DiIulio, Anthony ‘Caponi, Simmons Paul, Valerie Rogers HERE’S HOW YOU CAN HELP: • Continue to support policies and funding for systems to reduce infant mortality in Ohio. • Support policies to increase HIE utilization to support coordination of care across the care continuum in Ohio consistent with national standards. • Support the funding of health IT jobs and workforce development programs needed to implement the health IT objectives and regulatory changes in Ohio. Accountable Ohio by Dr. Mark Redding 1. Reduce Risk - Make risk reduction our State goal and focus on risk reduction for individual and family well-being. 2. Work as a Team - The comprehensive reduction of risk is the most evidence-based strategy for improving infant mortality and all other health, social and economic outcomes. Remove the silos standing between agencies, research organizations, community initiatives, and policy development in a focused State effort to accountably identify and address risk within populations most at-risk. 3. Require Evidence Based Coordination and Completion of Risk Reduction. Use all available evidence-based and promising practice models of both care coordination and direct service intervention across health, social, and behavioral health services, to assure that risks are identified and effectively addressed. Use technology and centralized data collection, in cooperation with government and community-based research teams, to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of risk reduction while reducing cost. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950. -

Download PDF Datastream

Twenty-First Century Black Mayors, Non-Majority Black Cities, And the Representation of Black Interests By Ravi Kumar Perry A.B., University of Michigan, 2004 A.M., Brown University, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2009 © Copyright 2009 by Ravi K. Perry iii This dissertation by Ravi Kumar Perry is accepted in its present form by the Department of Political Science as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date_____________ _________________________________ Marion Orr, Ph.D., Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date_____________ _________________________________ James Morone, Ph.D., Reader Date_____________ _________________________________ Wendy Schiller, Ph.D., Reader Date_____________ _________________________________ Darrell West, Ph.D., Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date_____________ _________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate School iv CURRICULUM VITAE Ravi Kumar Perry 144 S. Fitzhugh St. Telephone: (401) 261-7395 Apartment #1 (585) 275-5149 Rochester, NY 14608 Email: [email protected] Education 2005-current Ph.D. (Expected May 2009), Brown University, Political Science Dissertation: “21st Century Black Mayors, Non-Majority Black Cities, and the Representation of Black Interests.” The dissertation is an examination of the conditions under which Black mayors of non-majority Black cities actively pursue policies designed to improve the quality of life of Black residents and examines the implications of two phenomena: demographic changes in many American cities that are steadily reversing the population dynamics that brought about the election of this nation’s first African-American mayors and how the election of a Black mayor is viewed by Black residents with high expectations and as a result as an opportunity to see city government work in their interests and to address inequities. -

“Legislature” and the Elections Clause

Copyright 2015 by Michael T. Morley Vol. 109 Northwestern University Law Review THE INTRATEXTUAL INDEPENDENT “LEGISLATURE” AND THE ELECTIONS CLAUSE Michael T. Morley* INTRODUCTION The Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution is the Swiss army knife of federal election law. Ensconced in Article I, it provides, “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations.”1 Its Article II analogue, the Presidential Electors Clause, similarly specifies that “[e]ach State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors” to select the President.2 The concise language of these clauses performs a surprisingly wide range of functions implicating numerous doctrines and fields beyond voting rights, including statutory interpretation,3 state separation of powers and other issues of state constitutional law,4 federal court deference to state-court rulings,5 administrative discretion,6 and preemption.7 * Assistant Professor, Barry University School of Law. Climenko Fellow and Lecturer on Law, Harvard Law School, 2012–14; J.D., Yale Law School, 2003; A.B., Princeton University, 2000. Special thanks to Dr. Ryan Greenwood of the University of Minnesota Law Library, as well as Louis Rosen of the Barry Law School library, for their invaluable assistance in locating historical sources. I also am grateful to Terri Day, Dean Leticia Diaz, Frederick B. Jonassen, Derek Muller, Eang Ngov, Richard Re, Seth Tillman, and Franita Tolson for their comments and suggestions. I was invited to present some of the arguments from this Article in an amicus brief on behalf of the Coolidge-Reagan Foundation in Arizona State Legislature v. -

RESOLUTION NO.: 50-2007 OFFERED BY: Mayor Ursu and All of Council

RESOLUTION NO.: 50-2007 OFFERED BY: Mayor Ursu and All of Council A RESOLUTION OPPOSING OHIO SUBSTITUTE SENATE BILL 117 AND SUPPORTING THE LOCAL CABLE FRANCHISING PROCESS; AND DECLARING AN EMERGENCY WHEREAS, Substitute Senate Bill (“Sub. SB”) 117 was passed in the Ohio Senate on May 9, 2007 and the bill was immediately forwarded to the Ohio House of Representatives where it is being reviewed by the House Public Utilities Committee in which Sponsor’s introduction and proponents' hearing is expected to commence on May 23, 2007 with opponents' hearing to follow; and WHEREAS, in its present form, Sub. SB 117 continues to provide for the elimination of local franchise authority over cable and other video service providers that must use the City’s rights-of-way to provide service and would replace that authority with only the most minimal oversight and enforcement powers by the Ohio Director of Commerce; and WHEREAS, Sub. SB 117 would permit cable operators to unilaterally abrogate and abandon existing cable/video contracts with municipalities even if no new competitive video service is offered in those communities and would outlaw the extension of any current franchise agreement thereby abrogating the City's current franchise agreement with Time Warner Cable which was negotiated in good faith; and WHEREAS, Sub. SB 117 will continue to reduce the franchise fees paid to the City by cable operators and/or other video service providers in exchange for using the City’s rights-of- way, and would severely impair the City’s ability to audit cable and competitive video service providers’ franchise fee payments; and WHEREAS, Sub.