Download PDF Datastream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lucas County, Ohio 2017 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report

Lucas County, Ohio 2017 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Issued by Anita Lopez, Esq., Lucas County Auditor For the Year Ended December 31, 2017 CAFR Lucas County, Ohio For the Year Ended December 31, 2017 Lucas County, Ohio Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2017 Anita Lopez, Esq. Lucas County Auditor The CAFR and CEFS Team Finance Department Amy Petrus Chief Deputy Auditor Anthony Stechschulte Director of Accounting and Internal Control Ellen Lauderman, CPA Chief Accountant Public Information Department Vincent Wiggins Assistant Chief of Staff Mely Arribas-Douglas Research and Development Specialist LUCAS COUNTY, OHIO Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Year Ended December 31, 2017 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTORY SECTION Letter of Transmittal ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Elected Officials ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Organizational Chart ........................................................................................................................................ 9 GFOA Certificate of Achievement ...................................................................................................................10 II. FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditors’ Report ..........................................................................................................................11 -

International Broadcasting Network

Page I of I INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING NETWORK From: INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING NETWORK <[email protected]> To: <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, June 26, 2001 1:36 PM SUbject: Re: KTRE Channel Application June 26, 2001 Dear Ms. Bedard, Many thanks for your e-mail of yesterday. We certainly understand that the many Issues and problems surrounding DTV have kept Mr. Smith quite busy. Although we don't have to deal with those issues in the same way your company does, it is quite apparent that DTV has been a disaster and many in the industry wish it would just go away. From what we've been hearing, many stations are extremely reluctant to build DTV facilities and definitely won't meet the deadline. Just a few days ago, one large group owner began a major lobbying effort to persuade Congress to allow DTV permits to be tumed back in. With DTV having been a failure in the marketplace, with the technical and legal issues that remain, with the lack of any business model that could sustain DTV operations and with the networks' plans to reduce or eliminate compensation to affiliates, there doesn't seem to be a reason (other than the federal mandate) for DTV transmission systems to be built. From IBN's standpoint. we want to keep all of our stations on the air. We don't sell airtime or commercials. but our mission is very important to us and to our viewers. The loss of our stations in Lufkin, Longview and Crockett would be devastating. From your company's standpoint, perhaps it would be desirable to seek a moratorium on DTV buildout obligations, especially in small and medium-sized markets. -

Chamber Addresses Jobs and the Economy at L.A. City Hall Standing

Chamber VOICE IN THIS ISSUE: 10 ways the Chamber helped L.A. business this quarter 3 Chamber Southern California Leadership Network grooms leaders 4 Chamber forms new Non Profit Council 6 FALL 2007 • VolumE 6 • issue 4 VOICE A quarterly publication of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce Chamber addresses jobs and the economy at L.A. Standing with the City Hall Governor on health care reform The Chamber advocated for issues important to the City of Los Angeles at annual Access L.A. City Hall event he Los early 400 business leaders Garcetti echoed the need for more Angeles gathered for the Los collaboration, mentioning his efforts to Area Angeles Area Chamber make the council more aware of business Chamber of of Commerce’s annual issues through the creation of the Jobs, Commerce Access L.A. City Hall event Business Growth and Tax Reform endorsed Gov. committee. Chick suggested Arnold Schwarzenegger’s the need for a citywide health care reform economic development proposal in September, making it one of the first policy that would help business organizations to businesses grow and plan for come out in support of their future. the plan. Throughout the morning, The proposal includes a Chamber members heard 4 percent payroll fee on REFORMING HEALTH CARE. Chamber Board Chair David Fleming, Latham & Watkins, LLP, and Chamber President & CEO Gary Toebben discuss health care from more than 30 civic employers with 10 or with Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger after a Capitol News Conference on Sept. 17. leaders and lawmakers on more employees who do key issues in Los Angeles. -

Ohio Senate Journal

JOURNALS OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OHIO SENATE JOURNAL TUESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2011 22 SENATE JOURNAL, TUESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2011 FIFTH DAY Senate Chamber, Columbus, Ohio Tuesday, January 11, 2011, 1:30 p.m. The Senate met pursuant to adjournment. Prayer was offered by Father Michael Lumpe, St. Catharine's Church, Bexley, Ohio, followed by the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag. The journal of the last legislative day was read and approved. On the motion of Senator Faber the Senate advanced to the ninth Order of Business, Offering of Resolutions. OFFERING OF RESOLUTIONS Senator Faber offered the following resolution: S. R. No. 4-Senator Faber. Relative to the appointment of Peggy B. Lehner, to fill the vacancy in the membership of the Senate created by the resignation of Jon Husted of the 6th Senatorial District. WHEREAS, Section 11 of Article II, Ohio Constitution, provides for the filling of a vacancy in the Senate by appointment by the members of the Senate who are affiliated with the same political party as the person last elected to the seat which has become vacant; and WHEREAS, Jon Husted of the 6th Senatorial District has resigned as a member of the Senate effective January 9, 2011, thus creating a vacancy in the Senate; now therefore be it RESOLVED, By the members of the Senate who are affiliated with the Republican party, that Peggy B. Lehner (Republican), having the qualifications set forth in the Ohio Constitution and the laws of Ohio to be a member of the Senate from the 6th Senatorial District is hereby appointed, pursuant to Section 11 of Article II, Ohio Constitution, as a member of the Senate from the 6th Senatorial District, to fill the vacancy created by Jon Husted; and be it further RESOLVED, That a copy of this Resolution be spread upon the journal of the Senate together with the yeas and nays of the members of the Senate affiliated with the Republican party voting on the Resolution, and that the Clerk of the Senate shall certify the Resolution and the vote on its adoption to the Secretary of State. -

April 13, 2013

InteTOLEDO SISTrnationalER CITIES APRIL 13, 2013 A Welcome From The International Festival The University of Toledo 2013 Co-Chairs along with Intern in Ohio On behalf of Toledo Sister Cities International and The University of Toledo, we welcome you to the 4th Annual International Festival. This year’s event marks the first festival partnership between The University of Toledo (UT) would like to and Toledo Sister Cities International (TSCI). We have a day filled with the celebration of our diverse cultures, including international performances featuring music, dance, martial arts and more; cultural exhibits; a special area in which to welcome you learn about the languages of many countries and try those newly acquired skills; interactive activities for children from kindergarten through university levels; and to the opportunities to taste and enjoy various ethnic foods provided by area restaurants. 2013 Toledo Sister Cities The International Festival was brought back to Toledo four years ago by a committed group of leaders International Festival! within TSCI who recognized the cultural diversity of our region and wanted to celebrate both the uniqueness and commonalities shared among those living in our metropolitan area, comprised of northwest Ohio/southeast Michigan. For the past three years the event was held at the Erie Street Market and has grown yearly. Today, UT and the Center for International Studies and Programs (CISP) share great pride knowing that the festival will take place in our newly renovated Student Union Auditorium, aiding CISP’s mission to facilitate cross-cultural interaction among students, faculty and staff that leads to better global understanding, an enriched personal experience, and a more peaceful world. -

U.S. Mayors to Meet with President Barack Obama at the White House on Friday, February 20, 2009

For Immediate Release: Contact: Elena Temple Wednesday, February 19, 2009 202-309-4906 ([email protected]) Carlos Vogel 202-257-9797 ([email protected]) U.S. MAYORS TO MEET WITH PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA AT THE WHITE HOUSE ON FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2009 Washington, D.C. – The nation’s mayors have been invited by U.S. President Barack Obama and U.S. Vice President Joseph Biden to the White House for a meeting with The Conference of Mayors leadership on the morning of Friday, February 20, 2009. Led by U.S. Conference of Mayors President Miami Mayor Manny Diaz, over 60 mayors will also meet with Attorney General Eric H. Holder, Jr., Housing and Urban Development Secretary Shaun Donovan, Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, Energy Secretary Dr. Steven Chu, Education Secretary Arne Duncan and White House Senior Staff. The mayors meeting with President Obama and Vice President Biden will take place from 10:30 a.m. to 11:15 a.m. in the East Room of the White House and will be OPEN to the press. The mayors will also hold a press availability at the White House at 11:30 a.m. immediately following the meeting (location is TBD). Following the White House meeting, the mayors will gather at the Capitol Hilton in Washington, D.C. for a session with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lisa Jackson, U.S. Department of Energy Weatherization Program Director Gil Sperling, and U.S. Department of Justice COPS Office Acting Director Tim Quinn. This meeting is CLOSED to the press. The nation’s mayors commend President Obama and Congress for the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which is in line with the U.S. -

Mari Evans Honored Page 5

Volume 12, No.23 October 10, 2007 In This Issue The Truth Editorial SCHIP Veto Page 2 Ford Campaign Page 4 Mari Evans Honored Page 5 Toledo’s Tyler Perry Page 6 The Education Section Chris Myers Board Candidate Page 7 Africana Studies Page 8 Stewart Rebuilt Page 9 NW Ohio Scholarship Fund Page 10 Minister Gets Reel Page 11 The Lima Truth Pages 12-13 BlackMarketPlace Page 14 Classifieds Page 15 MariMari EvansEvans Commandress Ball Author,Author, Essayist,Essayist, Playwright,Playwright, andand PoetPoet Page 16 “Speak the truth to the people. Talk sense to the people. Free them with honesty. Free the people with Love and Courage for their Being. Spare them the fantasy. Fantasy enslaves. A slave is enslaved. Can be enslaved by unwisdom.” Page 2 The Sojourner’s Truth October 10, 2007 This Strikes Us … Community Calendar A Sojourner’s Truth Editorial *October 10-12 As promised, President George Bush vetoed a bill that would have increased spending Christian Community Church’s Kingdom Unlimited 2007: “Responding to the Call;” for the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) last week. Prayer Clinic at 6 pm nightly; Simon Gordon of Chicago is the guest speaker on Oct. 10 According to statements Bush has made over the past few months, he deplores the fact at 7 pm; Bishop Randy Borders of NC is speaker on Oct. 11 and 12 at 7 pm: 419-536-8357 that the program “is going beyond the initial intent of helping poor children.” Now the Mt. Ararat MBC: Fall revival; 7 pm each night; Evangelist Rev. -

12Th Grade Curriculum

THE TOM BRADLEY PROJECT STANDARDS: 12.6.6 Evaluate the rolls of polls, campaign advertising, and controversies over campaign funding. 12.6.6 Analyze trends in voter turnout. COMMON CORE STATE KEY TERMS AND ESSAY QUESTION STANDARDS CONTENT Reading Standards for Literacy in elections History/Social Studies 6-12 How did the election of Tom shared power Bradley in 1973 reflect the local responsibilities and Writing Standard for Literacy in building of racial coalitions in authority History/Social Studies 6-12 voting patterns in the 1970s and Text Types and Purpose the advancement of minority 2. Write informative/explanatory texts, opportunities? including the narration of historical events, scientific procedures/experiments, or technical processes. B. Develop the topic with relevant, well-chosen facts, definitions, concrete details, quotations, or other information and expamples LESSON OVERVIEW MATERIALS Doc. A LA Times on Voter turnout, May 15, 2003 Day 1 View Module 2 of Tom Bradley video. Doc. B Voter turnout spreadsheet May 15, 2003 (edited) Read Tom Bradley biography. Doc. C Statistics May 15,2003 Day 2 Doc. D Tom Bradley biography Analyze issues related to voter turnout in Doc. E Census, 2000 2013 Los Angeles Mayoral Election and Doc, F1973 Mayoral election connections to the 1973 campaign for Doc .G Interview 1973 Mayor. Doc. H Election Night speech 1989 Day 3 Doc I LA Times Bradley’s first year 1974 Analyze issues in 1973 campaign. Doc. J LA Times Campaign issues 1973 Analyze building of racial coalitions Doc K LA Times articles 1973 among voters. Day 4 Doc. L LA Times campaign issues 1973 Write essay. -

A Reception with Ohio's Big City Mayors

OHIO MAYORS ALLIANCE A BIPARTISAN COALTION OF MAYORS IN OHIO’S LARGEST CITIES PLEASE JOIN US FOR A RECEPTION WITH OHIO’S BIG CITY MAYORS Thursday, Dec. 6, 2018 | 9:00 AM to 10:00 AM | Dublin, Ohio | Bridge Street District OHIO MAYORS ALLIANCE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Mayor John Cranley Mayor Tim DeGeeter Mayor Andrew J. Ginther Mayor Don Patterson City of Cincinnati City of Parma City of Columbus City of Kettering Mayor Lydia Mihalik Mayor Larry Mulligan, Jr. Mayor Nan Whaley City of Findlay City of Middletown City of Dayton OHIO MAYORS ALLIANCE MEMBERS Mayor Daniel Horrigan, City of Akron Mayor Richard “Ike” Stage, City of Grove City Mayor Bob Stone, City of Beavercreek Mayor Patrick Moeller, City of Hamilton Mayor Tom Bernabei, City of Canton Mayor Mike Summers, City of Lakewood Mayor Carol Roe, City of Cleveland Heights Mayor David J. Berger, City of Lima Mayor Don Walters, City of Cuyahoga Falls Mayor Chase Ritenauer, City of Lorain Mayor Gregory S. Peterson, City of Dublin Mayor Warren R. Copeland, City of Springfield Mayor Holly C. Brinda, City of Elyria Mayor Wade Kapszukiewicz, City of Toledo Mayor Kirsten Holzheimer Gail, City of Euclid Mayor William D. Franklin, City of Warren Mayor Steve Miller, City of Fairfield Mayor Tito Brown, City of Youngstown EVENT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES HOST: $2,500 Recognition of sponsorship at breakfast reception and logo displayed on OMA membership meeting materials, 4 tickets to breakfast reception SPONSOR: $1,000 Recognition at breakfast reception, 2 tickets to breakfast reception GUEST: $500 1 ticket to breakfast reception Few organizations bring leaders from both sides of the aisle together to solve problems. -

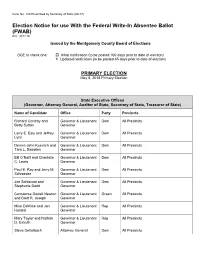

Election Notice for Use with the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C

Form No. 120 Prescribed by Secretary of State (09-17) Election Notice for use With the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C. 3511.16 Issued by the Montgomery County Board of Elections BOE to check one: Initial notification (to be posted 100 days prior to date of election) X Updated notification (to be posted 45 days prior to date of election) PRIMARY ELECTION May 8, 2018 Primary Election State Executive Offices (Governor, Attorney General, Auditor of State, Secretary of State, Treasurer of State) Name of Candidate Office Party Precincts Richard Cordray and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Betty Sutton Governor Larry E. Ealy and Jeffrey Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Lynn Governor Dennis John Kucinich and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Tara L. Samples Governor Bill O’Neill and Chantelle Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts C. Lewis Governor Paul E. Ray and Jerry M. Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Schroeder Governor Joe Schiavoni and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Stephanie Dodd Governor Constance Gadell-Newton Governor & Lieutenant Green All Precincts and Brett R. Joseph Governor Mike DeWine and Jon Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts Husted Governor Mary Taylor and Nathan Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts D. Estruth Governor Steve Dettelbach Attorney General Dem All Precincts Dave Yost Attorney General Rep All Precincts Zack Space Auditor of State Dem All Precincts Keith Faber Auditor of State Rep All Precincts Kathleen Clyde Secretary of State Dem All Precincts Frank LaRose Secretary of State Rep All Precincts Rob Richardson Treasurer of State Dem All Precincts Sandra O’Brien Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Robert Sprague Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Paul Curry (Write-In) Treasurer of State Green All Precincts U.S. -

LUCAS COUNTY, OHIO Single Audit Reports Year Ended December 31, 2016

LUCAS COUNTY, OHIO Single Audit Reports Year Ended December 31, 2016 Board of County Commissioners Lucas County One Government Center, Ste 600 Toledo, OH 43604 We have reviewed the Independent Auditor’s Report of Lucas County, prepared by Clark, Schaefer, Hackett & Co., for the audit period January 1, 2016 through December 31, 2016. Based upon this review, we have accepted these reports in lieu of the audit required by Section 117.11, Revised Code. The Auditor of State did not audit the accompanying financial statements and, accordingly, we are unable to express, and do not express an opinion on them. Our review was made in reference to the applicable sections of legislative criteria, as reflected by the Ohio Constitution, and the Revised Code, policies, procedures and guidelines of the Auditor of State, regulations and grant requirements. Lucas County is responsible for compliance with these laws and regulations. Dave Yost Auditor of State June 15, 2017 88 East Broad Street, Fifth Floor, Columbus, Ohio 43215‐3506 Phone: 614‐466‐4514 or 800‐282‐0370 Fax: 614‐466‐4490 www.ohioauditor.gov This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Schedule of Expenditures of Federal Awards............................................................................1 – 7 Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting and on Compliance and Other Matters Based on an Audit of Financial Statements Performed in Accordance with Government Auditing Standards..............................................................8 – 9 Report on Compliance for -

Candidates That Have Been Certified to the Ballot for the November 8, 2005 General Election

CANDIDATES THAT HAVE BEEN CERTIFIED TO THE BALLOT FOR THE NOVEMBER 8, 2005 GENERAL ELECTION CITY OF MAUMEE COUNCIL (4 To Be Elected) Brent Buehrer - Republican Michael J. Coyle - Democrat 721 River Glen Road 208 E. Dudley Street Maumee, Ohio 43537 Maumee, Ohio 43537 Richard H. Carr - Republican David Westrick - Democrat 717 Meadow Springs Court 220 W. Wayne Street Maumee, Ohio 43537 Maumee, Ohio 43537 Timothy L. Pauken - Republican Maria Zapiecki - Democrat 1225 Holgate Avenue 127 W. John Street Maumee, Ohio 43537 Maumee, Ohio 43537 JUDGE OF THE MUNICIPAL COURT (1 To Be Elected) Full Term Commencing 1/1/06 Gary L. Byers 224 E. Harrison Street Maumee, Ohio 43537 CITY OF OREGON MAYOR (1 To Be Elected) Marge Brown 3144 Seaman Street Oregon, Ohio 43616 1 CITY OF OREGON - CONTINUED COUNCIL (7 To Be Elected) Marvin Belknap Jerry Peach 630 Anmarie Court 6113 Navarre Avenue Oregon, Ohio 43616 Oregon, Ohio 43618 Sandy Bihn James S. Seaman 6565 Bayshore Drive 3555 Williamsburg Drive Oregon, Ohio 43618 Oregon, Ohio 43616 Sharon Graffeo-Rudess Michael J. Seferian 3251 Springtime Drive 535 S. Stadium Road Oregon, Ohio 43616 Oregon, Ohio 43616 Doug Joyce Michael P. Sheehy 2052 Lakeview Avenue 1129 Schmidlin Road Oregon, Ohio 43618 Oregon, Ohio 43616 Steven M. Kusian Matthew A. Szollosi 1138 Earlwood Avenue 1660 Grand Bay Drive Oregon, Ohio 43616 Oregon, Ohio 43616 Paul Lambrecht 123 Springwood Street West Oregon, Ohio 43616 JUDGE OF THE MUNICIPAL COURT (1 To Be Elected) Full Term Commencing 1/1/06 Gary A. Breier Jeffery B. Keller 5040 Eagles Landing 504 Bridgewater Drive Oregon, Ohio 43616 Oregon, Ohio 43616 Cherrefe A.