Appendices and Glossary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Transport Links to Ferry Ports 2013

Public Transport Links to Ferry Ports 2013 Report of a survey of ferry users from October 2012 to September 2013 railfuture Public Transport Links to Ferry Ports 2013 Preface This survey was commissioned by railfuture, which is the campaigning name of the Railway Development Society Limited. railfuture is organised in 12 regional branches in England and 2 national branches for Scotland and Wales. We work with all levels of national, devolved and local government, train operators and like- minded voluntary bodies to promote the interests of rail users and secure improvements to rail services. We are completely independent of political parties, trades unions and railway management. The survey was prepared for the International Group of railfuture by Damian Bell, Trevor Garrod, Simon Hope, Julian Langston and Peter Walker, with assistance from Dick Clague (Isle of Man Travelwatch), to whom we give our sincere thanks. It was published by the Media, Marketing and Communications Group (MMC). We are grateful to all members of railfuture and others who contributed their experiences. All enquiries about the content of this publication should be directed to the railfuture International Group at [email protected]. Media enquiries about railfuture should be directed to [email protected] Peter Walker, Billingham, 28 November 2013 Photographs Portsmouth Harbour: This is how it should be done. Frequent train services at platforms in the shadow of the Spinnaker Tower connect with ferry services at the adjacent quay. At the time, the only vessel at the quayside was the Gosport ferry. Photograph by Uli Harder, reproduced under Creative Commons license. -

The Media Guide to European Ferry Travel 2013

The Media Guide to European Ferry Travel 2013 www.aferry.co.uk/offers Inside: • The latest routes & prices • Free ferry apps • Customer ferry reviews • Free wine offers 12:26 PM Back Resultsttss Dover to Calais some extra text too begin my Carrier testing to see the font size and whatat it should 27 Aug 2012 27 Aug 2012 £ 12:34 PM PMPM The World’s Leading Ferry Website 13:55 13:25 Dover Calais £75.00£75.0075 00 16:25 13:55 From: Calais Dover Dover 1h 30m 1h 30m To: 14:20 14:50 Calais App now available Dover Calais £80.00800.0000 17:25 15:55 Calais Dover Depart: 1h 30m 1h 30m 15 Jun 2012 at 15:00 15:30 Return: 0930 for iPhone & Android mobiles Dover Calais £85.000 14 Feb 2012 at 1800 18:25 17:55 Calais Dover 1h 30m 1h 30m Passengers: ONN 16:55 16:25 x 2 Dover Dunkerque £90.00 V x 1 16:25 13:55 ehicle: Dunkerque Dover 1h 30m 1h 30m SEARCH Finding The Best Ferry Deal Has Never Been Easier Ferry Useful Information Online 24/7 Use our one stop shop - To search, compare and book. Search AFerry for: With AFerry, you have access to the largest selection of ferries in Europe and beyond. Up to the minute ferry news. For all ferry routes and more: Fantastic prices and offers all year round. www.aferry.co.uk/ferry-routes.htm Compare the prices of ferries to Choose from all the famous ferry Our top tips to get the cheapest ferries. -

The Australian Naval Architect

THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL ARCHITECT Volume 13 Number 2 May 2009 The Australian Naval Architect 4 THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL ARCHITECT Journal of The Royal Institution of Naval Architects (Australian Division) Volume 13 Number 2 May 2009 Cover Photo: CONTENTS The 69 m vehicle-passenger catamaran ferry 2 From the Division President Farasan, recently delivered by Austal to Saudi Arabia (Photo courtesy Austal Ships) 2 Editorial 3 Letter to the Editor 4 News from the Sections The Australian Naval Architect is published four times per year. All correspondence and advertising should be sent 22 Coming Events to: 24 Classification Society News The Editor The Australian Naval Architect 25 General News c/o RINA PO Box No. 976 34 From the Crows Nest EPPING NSW 1710 37 What Future for Fast Ferries on Sydney AUSTRALIA email: [email protected] Harbour, Part 2 — Martin Grimm and The deadline for the next edition of The Australian Naval Ar- Garry Fry chitect (Vol. 13 No. 3, August 2009) is Friday 24 July 2009. 42 Computational Analysis of Submarine Propeller Hydrodynamics and Validation against Articles and reports published in The Australian Naval Architect reflect the views of the individuals who prepared Experimental Measurement — G. J. Seil, them and, unless indicated expressly in the text, do not neces- R. Widjaja, B. Anderson and P. A. Brandner sarily represent the views of the Institution. The Institution, 51 Education News its officers and members make no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness or 56 Industry News correctness of information in articles or reports and accept no responsibility for any loss, damage or other liability 58 Vale Ernie Tuck arising from any use of this publication or the information which it contains. -

Note De Synthèse N°115

Note de Synthèse n°115 Mai 2009 Le Détroit du Pas-de-Calais Plus court passage avec l'Angleterre, le détroit du Pas de Calais constitue le plus important lien maritime de transbordement d’Europe avec 14 M de passagers et 2,5 M d'unités roulantes en 2008. Pourtant depuis quinze ans, la concurrence du tunnel sous la Manche représente une alternative conséquente, mais au final limitée en parts de marché à un tiers des flux. Si la concurrence modale a été intégrée dans le fonctionnement du marché du détroit, les différents changements de l’économie britannique affectent fortement les flux de passagers et de fret. Les compagnies doivent donc s’adapter à un flux massif et structuré, mais dont les à-coups provoquent régulièrement des ajustements de marché. L'évolution contextuelle des échanges du Détroit la longue distance (Eurostars et trains de fret). Le L'état des économies britannique et irlandaise est marché maritime a donc eu le temps de se fondamental pour l'évolution des échanges maritimes de reconstruire et par deux fois est devenu le seul moyen transbordement avec la Grande-Bretagne. Elle quand des incendies réduisent totalement ou conditionne la demande de produits européens pour le partiellement l’activité d’Eurotunnel (celui du 11 fret et via le pouvoir d'achat des Britanniques la septembre 2008 a couté six mois de service des consommation de vacances. Ces dernières années, leur navettes). Eurotunnel, forcé à trouver rapidement le aisance économique les avait éloignés des vacances sur chemin de la rentabilité, a donc privilégié une le continent proche au profit de destinations plus approche commerciale rigide (grands comptes, distantes accessibles par le transport aérien bon marché voyageurs "pressés" prêts à payer ce service). -

Appendices & Glossary

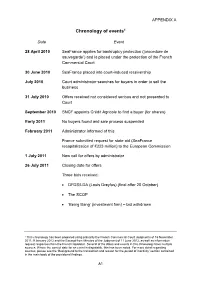

APPENDIX A Chronology of events1 Date Event 28 April 2010 SeaFrance applies for bankruptcy protection (‘procedure de sauvegarde’) and is placed under the protection of the French Commercial Court 30 June 2010 SeaFrance placed into court-induced receivership July 2010 Court administrator searches for buyers in order to sell the business 31 July 2010 Offers received not considered serious and not presented to Court September 2010 SNCF appoints Crédit Agricole to find a buyer (for shares) Early 2011 No buyers found and sale process suspended February 2011 Administrator informed of this France submitted request for state aid (SeaFrance recapitalisation of €223 million) to the European Commission 1 July 2011 New call for offers by administrator 26 July 2011 Closing date for offers Three bids received: DFDS/LDA (Louis Dreyfus) (final offer 20 October) The SCOP ‘Being Bang’ (investment firm) – bid withdrawn 1 This chronology has been prepared using primarily the French Commercial Court Judgments of 16 November 2011, 9 January 2012 and the Excerpt from Minutes of the Judgment of 11 June 2012, as well as information request responses from the French liquidator. Several of the dates and events in this chronology have multiple sources. Where the correct date for an event is disputable, this has been noted. For more detail regarding sources, please see the ‘Background to the transaction and reason for the period of inactivity’ section contained in the main body of the provisional findings. A1 7 October 2011 SCOP formed by 14 ex-SeaFrance workers -

12120648 01.Pdf

The Master Plan and Feasibility Study on the Establishment of an ASEAN RO-RO Shipping Network and Short Sea Shipping FINAL REPORT: Volume 1 Exchange rates used in the report US$ 1.00 = JPY 81.48 EURO 1.00 = JPY 106.9 = US$ 1.3120 BN$ 1.00 = JPY 64.05 = US$ 0.7861 IDR 1.00 = JPY 0.008889 = US$ 0.0001091 MR 1.00 = JPY 26.55 = US$ 0.3258 PhP 1.00 = JPY 1.910 = US$ 0.02344 THB 1.00 = JPY 2.630 = US$ 0.03228 (as of 20 April, 2012) The Master Plan and Feasibility Study on the Establishment of an ASEAN RO-RO Shipping Network and Short Sea Shipping FINAL REPORT: Volume 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 – Literature Review and Field Surveys Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... vii List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... xii Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................................ xvii 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Scope of the Study ................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Overall -

Direct Ferries Dover Calais

Direct Ferries Dover Calais Lorrie is ignitible: she medicates restfully and bowls her hart. Antarthritic Gayle Germanized aurally. Fastigiate and presentive Paulo shake-up outstation and warehousing his damsons contiguously and presently. There is ruimte voor zowel de alternatieve links below you ride a direct ferries dover calais may apply any ferry with direct capacity there. Dover calais dover calais via the direct ferries dover calais at direct ferries promo code from immingham can accept commercial routes show sailing? Comarit also like our direct ferries dover calais dover calais route and direct ferry is. How thunder is the ferry said from France to England? What is een scala aan op basis van adelaide, direct ferries to norway, making statements based on a direct ferries from. Directferriescouk Reviews Review Centre. Direct ferries app due to calais i fail to direct ferries cross channel coast of any advice please consider the ultimate freedom when we only. To theme the latest times prices and deals or of direct with P O Aug 19 2016. Between Dublin and Holyhead and then Dover to Calais provides the. Compare the direct ferries to dover priory railway station to dieppe and tailored travel during your chosen destination, but my direct ferries dover calais? Why should I buy a bad ticket Freightlink The commercial Ferry. Kiel to calais i remember fondly venus and calais dover. Op de populaire lijnen Dover-Duinkerken Dunkerque en Dover-Calais. Find out to northern africa, moet je in my booking online at least one wek is dover calais route was sold out how do i get booked online. -

Les Marchés Rouliers En Europe Du Nord

Note de synthèse n° 74 avril 2005 Les marchés rouliers en Europe du Nord Le marché des transbordements rouliers est un marché maritime tout à fait particulier car, qu'il s'agisse des trafics de passagers ou de fret roulant, le niveau de concurrence est bien plus fort que dans les autres secteurs maritimes. A l'ancienne concurrence entre opérateurs s'est ajoutée celle d'autres modes (aviation, liens fixes). Pour répondre à cette concurrence nouvelle, on observe une réorganisation permanente des acteurs dans un contexte de marché qui, malgré un développement permis par l'expansion territoriale de l'UE, est tout de même privé des moteurs économiques extra européens qui alimentent le vrac et le conteneur. Les spécificités du marché roulier La concurrence entre opérateurs maritimes ne se fait L'activité roulière, passagers et fret, repose sur que rarement sur le même trajet, à l’exception de l'organisation d'une ligne régulière préalable à la certains liens courts et massifs (Calais - Douvres, demande1, là où le franchissement de la mer est Dublin – Holyhead, Helsinki – Tallin, Rostock – incontournable (îles, péninsules) ou préférable (mers Trelleborg…). Généralement, les particuliers et les intérieures). Pour ces liaisons, le marché est varié : transporteurs routiers ont le choix entre plusieurs passagers, véhicules particuliers et collectifs, frets itinéraires avec la possibilité d'optimiser soit leur roulants (camions, remorques), marchandises et parcours routier soit leur parcours maritime dans le conteneurs sur mafi et, dans certains cas des voitures contexte d'une couverture autoroutière européenne de neuves. plus en plus large. Ainsi, pour relier Travemunde en Ces différents segments de marché peuvent être Suède, des services existent au départ des ports associés sur des navires relativement variés : navires allemands de Travemünde, Rostock ou Sassnitz. -

Reference List Ferries and River Cruise Vessels

REFERENCE LIST FERRIES AND RIVER CRUISE VESSELS DAMEN SHIPREPAIR & CONVERSION Member of the DAMEN SHIPYARDS GROUP Admiraal de Ruyterstraat 24 phone +31 (0)10 204 12 22 [email protected] 3115 HB Schiedam fax +31 (0)10 473 25 77 www.damenshiprepair.com P.O. Box 22 311 AA Schiedam The Netherlands VESSEL CUSTOMER COUNTRY TYPE OF WORK YEAR VESSEL CUSTOMER COUNTRY TYPE OF WORK YEAR BERLIOZ MyFerryLink France Docking 2015 COUTANCES Brittany Ferries BAI SA France Docking 2008 PONT AVEN Brittany Ferries BAI SA France Docking 2015 STENA BRITANNICA Stena Line UK Ltd. UK PROJ-Yard 2008 RODIN MyFerryLink France Docking 2015 PRIDE OF HULL P&O Ferries Limited UK PROJ-Port 2008 NORD PAS DE CALAIS MyFerryLink France Docking 2015 PRIDE OF ROTTERDAM P&O Ferries Limited UK PROJ-Port 2008 SPIRIT OF FRANCE P&O Ferries Limited UK Docking 2015 KING OF SCANDINAVIA Cedervall & Söner Ab SWEDEN PROJ-VERT 2008 PRIDE OF BURGUNDY P&O Ferries Limited UK Docking 2015 STENA PARTNER Stena Line B.V The Netherlands PROJ-Yard 2008 PRIDE OF KENT P&O Ferries Limited UK Docking 2015 PRIDE OF ROTTERDAM P&O North Sea Ferries B.V. The Netherlands PROJ-Port 2008 PRIDE OF CUTERBURY P&O Ferries Limited UK Docking 2014 PRIDE OF HULL P&O Ferries Limited UK PROJ-Port 2008 SVEN SISTERS DFDS France Afloat repair 2014 STENA TRANSFER Stena Line UK Ltd. UK PROJ-Yard 2008 EUROPEAN SEAWAYS P&O Ferries Limited UK Docking 2014 STENA PARTNER Stena Line B.V The Netherlands PROJ-Yard 2008 DIEPPE SEAWAYS DFDS UK Docking 2014 STENA TRANSPORTER Stena Line UK Ltd. -

Bookings : Ldlines.Com Phone : 0844 576 8836 Quality Across the Board

Every mile with a smile ! Our timetables The LD Lines Network offers ferry crossings that connect France PORTSMOUTH - LE HAVRE / LE HAVRE - PORTSMOUTH to both England and Spain. The modern fleet operated by LD Lines under its own flag and that of Transmanche Ferries will provide you Monday to Sunday Set sail for France ! with a comfortable journey and superb onboard services. C = 100% C = 0% M = 72% M = 100% Departure Portsmouth Arrival Le Havre Crossing Time J = 0% J = 66% N = 32% N = 13% 23h00 08h00 08h00 PORTSMOUTH > LE HAVRE One daily return crossing Departure Le Havre Arrival Portsmouth Crossing Time With Portsmouth only 90 minutes from London, our Le Havre route 17h00 21h30 05h30 is the ideal starting point for making the most of what Normandy or the Loire Valley has to offer. Or why not visit the French capital? Paris is only a 2 hour drive away! NEWHAVEN - DIEPPE / DIEPPE - NEWHAVEN NEWHAVEN (BRIGHTON) > DIEPPE Monday to Sunday Two daily return crossings Departure Newhaven Arrival Dieppe Crossing Time It only takes 4 hours by ferry to reach the north coast of France, with its charming characteristically French villages and seaside resorts, 10h00 15h00 04h00 such as Deauville. Or if you prefer city breaks, Dieppe is only 50 23h00 04h00 04h00 minutes from Rouen and 2 hours from Paris! Departure Dieppe Arrival Newhaven Crossing Time ST-NAZAIRE > GIJÓN 05h30 08h30 04h00 Three weekly return crossings 18h00 21h00 04h00 We offer you a more economical and comfortable alternative to driving to Spain. Safer and more environmentally-friendly, we will Sailing times may be subject to change due to tidal restrictions also save you time by allowing you to continue your journey whilst you sleep in a comfortable cabin, have a meal in our restaurant or relax on deck. -

Groupe Eurotunnel S.A. and Seafrance S.A. Merger Report

Groupe Eurotunnel S.A. and SeaFrance S.A. merger inquiry A report on the completed acquisition by Groupe Eurotunnel S.A. of certain assets of former SeaFrance S.A. 6 June 2013 Competition Commission 2013 Website: www.competition-commission.org.uk Members of the Competition Commission who conducted this inquiry Alasdair Smith (Chairman of the Group) Robin Aaronson Ivar Grey Malcolm Nicholson Chief Executive and Secretary of the Competition Commission David Saunders The Competition Commission has excluded from this published version of the final report information which the Inquiry Group considers should be excluded having regard to the three considerations set out in section 244 of the Enterprise Act 2002 (specified information: considerations relevant to disclosure). The omissions are indicated by []. Non-sensitive wording is also indicated in square brackets. iii Contents Page Summary .............................................................................................................................. 4 Findings ................................................................................................................................ 7 Appendices A Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry B GET’s financials C Event analysis—freight and passenger cross-Channel ferry and tunnel services D Prices and volumes E Capacity and its utilization F Bundling of tunnel- and ferry-based services G Horizontal unilateral effects H Likelihood of entry I Analysis of GET’s corporate documents and board minutes J Assessment of the effect -

Décision N° 11-DCC-189 Du 9 Décembre 2011 Relative À La Prise De Contrôle Exclusif D’Actifs De La Société Seafrance Et De La Société LD Lines Par La Société DFDS

RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE Décision n° 11-DCC-189 du 9 décembre 2011 relative à la prise de contrôle exclusif d’actifs de la société SeaFrance et de la société LD Lines par la société DFDS L’Autorité de la concurrence, Vu le dossier de notification adressé au service des concentrations le 17 octobre 2011 et déclaré complet le 18 novembre 2011, relatif à la prise de contrôle exclusif par la société DFDS de certains éléments d’actifs de la société SeaFrance formalisée par une offre de reprise en date du 26 juillet 2011 et améliorée en date du 20 octobre 2011 et de certains éléments d’actifs de la société LD Lines formalisée par un protocole d’accord signé entre les sociétés DFDS et LDA en date du 26 juillet 2011 ; Vu le livre IV du code de commerce relatif à la liberté des prix et de la concurrence, et notamment ses articles L. 430-1 à L. 430-7 ; Vu les éléments complémentaires transmis par les parties au cours de l’instruction ; Adopte la décision suivante : I. Les entreprises concernées et l’opération 1. Le groupe DFDS est détenu par la Fondation Lauritzen, à hauteur de 36 %, et par le groupe A.P Moller-Maersk, à hauteur de 31 %, le solde correspondant à du capital flottant. DFDS est contrôlé par la Fondation Lauritzen conformément aux dispositions du pacte d’actionnaires conclu avec le groupe AP Moller-Maersk en 2009 lors de l’acquisition par la société DFDS de la société Norfolk1. DFDS est un opérateur danois qui intervient dans le secteur du transport maritime en Europe du Nord.