A Three-Sided Mirror. the Basque Case. How Contemporary Literature Reflects Identity, Conflict and Memory in the ‘Spanish’ Basque Country: a Tridimensional Mirror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greco Eval IV Rep (2013) 5E Final Spain PUBLIC

F O U R T Adoption: 6 December 2013 Public Publication: 15 January 2014 Greco Eval IV Rep (2013) 5E H E V FOURTH EVALUATION ROUND A L Corruption prevention in respect of members of parliament, judges and prosecutors U A T I O EVALUATION REPORT N SPAIN R O Adopted by GRECO at its 62nd Plenary Meeting U (Strasbourg, 2-6 December 2013) N D 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... 3 I. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 6 II. CONTEXT .................................................................................................................................................. 8 III. CORRUPTION PREVENTION IN RESPECT OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT ................................................ 10 OVERVIEW OF THE PARLIAMENTARY SYSTEM ............................................................................................................... 10 TRANSPARENCY OF THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS ............................................................................................................. 11 REMUNERATION AND ECONOMIC BENEFITS ................................................................................................................. 12 ETHICAL PRINCIPLES AND RULES OF CONDUCT .............................................................................................................. 12 CONFLICTS OF INTEREST ......................................................................................................................................... -

Connections Between Sámi and Basque Peoples

Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Kent Randell 2012 Siidastallan Outside of Minneapolis, Minneapolis Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota “D----- it Jim, I’m a librarian and an armchair anthropologist??” Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Hard evidence: - mtDNA - Uniqueness of language Other things may be surprising…. or not. It is fun to imagine other connections, understanding it is not scientific Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Documentary: Suddenly Sámi by Norway’s Ellen-Astri Lundby She receives her mtDNA test, and express surprise when her results state that she is connected to Spain. This also surprised me, and spurned my interest….. Then I ended up living in Boise, Idaho, the city with the largest concentration of Basque outside of Basque Country Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota What is mtDNA genealogy? The DNA of the Mitochondria in your cells. Cell energy, cell growth, cell signaling, etc. mtDNA – At Conception • The Egg cell Mitochondria’s DNA remains the same after conception. • Male does not contribute to the mtDNA • Therefore Mitochondrial mtDNA is the same as one’s mother. Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Four generation mtDNA line Sisters – Mother – Maternal Grandmother – Great-grandmother Jennie Mary Karjalainen b. Kent21 Randell March (c) 2012 1886, --- 2012 Siidastallan,parents from Kuusamo, Finland Linwood Township, Minnesota Isaac Abramson and Jennie Karjalainen wedding picture Isaac is from Northern Norway, Kvaen father and Saami mother from Haetta Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, village. -

Seven Theses on Spanish Justice to Understand the Prosecution of Judge Garzón

Oñati Socio-Legal Series, v. 1, n. 9 (2011) – Autonomy and Heteronomy of the Judiciary in Europe ISSN: 2079-5971 Seven Theses on Spanish Justice to understand the Prosecution of Judge Garzón ∗ JOXERRAMON BENGOETXEA “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark” (Hamlet) Abstract Judges may not decide cases as they wish, they are subject to the law they are entrusted to apply, a law made by the legislator (a feature of heteronomy). But in doing so, they do not take any instruction from any other power or instance (this contributes to their independence or autonomy). Sometimes, they apply the law of the land taking into account the norms and principles of other, international, supranational, even transnational systems. In such cases of conform interpretation, again, they perform a delicate balance between autonomy (domestic legal order and domestic culture of legal interpretation) and heteronomy (external legal order and culture of interpretation). There are common shared aspects of Justice in the Member States of the EU, but, this contribution explores some, perhaps the most salient, features of Spanish Justice in this wider European context. They are not exclusive to Spain, but they way they combine and interact, and their intensity is quite uniquely Spanish. These are seven theses about Justice in Spain, which combine in unique ways as can be seen in the infamous Garzón case, discussed in detail. Key words Spanish Judiciary; Judicial statistics; Transition in Spain; Sociology of the Judiciary; Consejo General del Poder Judicial; Politicisation of Justice; Judicialisation of Politics; Spanish Constitutional Court; Spanish Supreme Court; Audiencia Nacional; Acusación Pública; Judge Garzón; Basque Political Parties; Clashes between Judicial Hierarchies ∗ Universidad del País Vasco – Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, [email protected] This research has been carried out within the framework of a research project on Fundamental Rights After 1 Lisbon (der2010-19715, juri) financed by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. -

How Can a Modern History of the Basque Country Make Sense? on Nation, Identity, and Territories in the Making of Spain

HOW CAN A MODERN HISTORY OF THE BASQUE COUNTRY MAKE SENSE? ON NATION, IDENTITY, AND TERRITORIES IN THE MAKING OF SPAIN JOSE M. PORTILLO VALDES Universidad del Pais Vasco Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada (Reno) One of the more recurrent debates among Basque historians has to do with the very object of their primary concern. Since a Basque political body, real or imagined, has never existed before the end of the nineteenth century -and formally not until 1936- an «essentialist» question has permanently been hanging around the mind of any Basque historian: she might be writing the histo- ry of an non-existent subject. On the other hand, the heaviness of the «national dispute» between Basque and Spanish identities in the Spanish Basque territories has deeply determined the mean- ing of such a cardinal question. Denying the «other's» historicity is a very well known weapon in the hands of any nationalist dis- course and, conversely, claiming to have a millenary past behind one's shoulders, or being the bearer of a single people's history, is a must for any «national» history. Consequently, for those who consider the Spanish one as the true national identity and the Basque one just a secondary «decoration», the history of the Basque Country simply does not exist or it refers to the last six decades. On the other hand, for those Basques who deem the Spanish an imposed identity, Basque history is a sacred territory, the last refuge for the true identity. Although apparently uncontaminated by politics, Basque aca- demic historiography gently reproduces discourses based on na- - 53 - ESPANA CONTEMPORANEA tionalist assumptions. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Basque Studies

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Basque Literature Series launched at Frankfurt Book Fair FALL Reported by Mari Jose Olaziregi director of Literature across Frontiers, an 2004 organization that promotes literature written An Anthology of Basque Short Stories, the in minority languages in Europe. first publication in the Basque Literature Series published by the Center for NUMBER 70 Basque Studies, was presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair October 19–23. The Basque Editors’ Association / Euskal Editoreen Elkartea invited the In this issue: book’s compiler, Mari Jose Olaziregi, and two contributors, Iban Zaldua and Lourdes Oñederra, to launch the Basque Literature Series 1 book in Frankfurt. The Basque Government’s Minister of Culture, Boise Basques 2 Miren Azkarate, was also present to Kepa Junkera at UNR 3 give an introductory talk, followed by Olatz Osa of the Basque Editors’ Jauregui Archive 4 Association, who praised the project. Kirmen Uribe performs Euskal Telebista (Basque Television) 5 was present to record the event and Highlights 6 interview the participants for their evening news program. (from left) Lourdes Oñederra, Iban Zaldua, and Basque Country Tour 7 Mari Jose Olaziregi at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Research awards 9 Prof. Olaziregi explained to the [photo courtesy of I. Zaldua] group that the aim of the series, Ikasi 2005 10 consisting of literary works translated The following day the group attended the Studies Abroad in directly from Basque to English, is “to Fair, where Ms. Olaziregi met with editors promote Basque literature abroad and to and distributors to present the anthology and the Basque Country 11 cross linguistic and cultural borders in order discuss the series. -

Erabaki Eskubidea Helburu Elkarlanerako Prest, Modua Eta Denborak Adostu Behar

TERMOMETROA MARIAN BEITIALARRANGOITIA - MARKEL OLANO Erabaki eskubidea helburu elkarlanerako prest, modua eta denborak adostu behar Marian Beitialarrangoitia (Legazpi, 1968) EH Bilduko Eusko Legebiltzarreko parlamentaria eta Hernaniko alkate ohia da. Markel Olano (Beasain, 1965) EAJko biltzarkidea da Gipuzkoan eta lurraldeko diputatu nagusi ohia. Autogobernuaz jarduteko bildu ditugu. Adostasun nagusia: Euskal Herria subjektu politiko gisa eta bere erabaki eskubidea ordenamendu juridikoetan finkatu behar dira. Desadostasuna denboretan da. | XABIER LETONA | Argazkiak: Dani Blanco Autogobernuari begira hainbat urrats batean, burujabetza nahi hori estal- rretxe lehendakariak nahi izan zuen eman dira azken hamarkadetan Eus- tzeko egin zen. Urrats praktikoak erabaki eskubidea finkatu, hartutako kal Herrian. Non gaude orain? Zein da pentsatzeko aukera dugu orain. erabakiak gure borondatearen une honetan autogobernuaz egiten M. Olano: Momentu batean argi ondorio izan zitezen eta ez tresneria duzuen diagnostikoa? ikusi zen Gernikako Estatutua eta konstituzionalaren araberakoak. Markel Olano: Une honetan bada- Foru Hobekuntzaren bidetik egin- go autogobernuan urrats berri bat dako bideek ez zutela etorkizunik. Espainian eredu federalaz hitz egiten emateko aukera, bai Euskal Herrian Ibarretxe lehendakaria izan zen hori hasi da berriz. Espero duzue zerbait eta, lidergo puntu batekin, baita ikusarazi zuena. Berak orduan egin- hausnarketa horietatik? EAEn ere. Paraleloan, bakea jorra- dako diagnostikoak orain ere balio M. Beitialarrangoitia: Estatuaren tzeko aukera berriak ireki dira eta, du. Irakurketa hartan, zein zen aldetik ezin da ezer espero eta ez beraz, orain arte bai jarrera politiko- Espainiako ikuspegia euskal autogo- dut uste Estatuak benetako izaera an eta bai ikuspegi estrategikoan oso bernuari buruz? Estatua ez zen demokratikoa erakutsiko duenik. bereiziak ziren tradizio politikoak aldebiko ikuspegia jorratzen ari eta Aldebikotasunaz hitz egin duzu bateratzeko aukera dugu. -

Canonical and Non-Canonical Narrative in the Basque Context

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hedatuz Canonical and non-canonical narrative in the basque context Olaziregi Alustiza, María José Euskal Herriko Unib. Filologia, Geografia eta Historia Fak. Unibertsitateko ibilbidea, 5. 01006 Vitoria-Gateiz [email protected] BIBLID [0212-7016 (2001), 46: 1; 325-336] Artikulu honetan euskal narratibaren egungo egoeraz egiten da hausnarketa. XX. mendean sendotuz joan den generoa dugu narratibazkoa eta gaur egungo euskarazko literatur produkzioan protagonismo erabatekoa du. Horretaz hitz egiten da artikuluan, narratibaren bilakaeraz eta egungo egoeraz. Guztiaren osagarri, euskal literatur sistema, euskal literaturak Espainian nahiz atzerrian duen proiekzio eskasa eta azken urteotako eleberriaren joera nagusiak aztertzen dira. Giltza-Hitzak: Literatur kritika. Literaturaren Historia. Euskal Literatura. Literatura Konparatua. En el presente artículo se reflexiona sobre la situación actual de la literatura vasca. La narrativa es un género que ha ido fortaleciéndose durante el siglo XX y que hoy en día detenta el protagonismo absoluto en la producción de la literatura en lengua vasca. De todo ello se habla en este artículo, de la evolución de la narrativa y de su situación actual. Para completar el trabajo se estudian la escasa proyección que en España y en en el extranjero tiene el sistema de literatura vasca, la literatura vasca, y las principales tendencias de la novela en estos últimos años. Palabras Clave: Crítica Literaria. Historia de la Literatura. Literatura Vasca. Literatura Comparada. Dans cet article, on examine la situation actuelle de la littérature basque. Le roman est un genre qui s’est affirmé durant le XXe siècle et qui détient aujourd’hui la primeur absolue dans la production de la littérature en langue basque. -

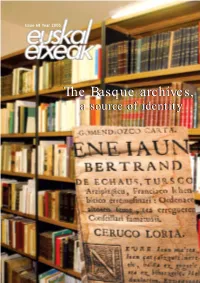

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina -

The Basque Experience with the Irish Model

WORKING PAPERS IN CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND SOCIAL JUSTICE ISSN 2053-0129 (Online) From Belfast to Bilbao: The Basque Experience with the Irish Model Eileen Paquette Jack, PhD Candidate School of Politics, International Studies and Philosophy, Queen’s University, Belfast [email protected] Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice CTSJ WP 06-15 April 2015 Page | 1 Abstract This paper examines the izquierda Abertzale (Basque Nationalist Left) experience of the Irish model. Drawing upon conflict transformation scholars, the paper works to determine if the Irish model serves as a tool of conflict transformation. Using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), the paper argues that it is a tool, and focuses on the specific finding that it is one of many learning tools in the international sphere. It suggests that this theme can be generalized and could be found in other case studies. The paper is located within the discipline of peace and conflict studies, but uses a method from psychology. Keywords: Conflict transformation, Basque Country, Irish model, Peace Studies Introduction1 The conflict in the Basque Country remains one of the most intractable conflicts, and until recently was the only conflict within European borders. Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) has waged an open, violent conflict against the Spanish state, with periodic ceasefires and attempts for peace. Despite key differences in contexts, the izquierda Abertzale (‘nationalist left’) has viewed the Irish model – defined in this paper as a process of transformation which encompasses both the Good Friday Agreement (from here on referred to as GFA) and wider peace process in Northern Ireland – with potential. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

“Behind-The-Table” Conflicts in the Failed Negotiation for a Referendum for the Independence of Catalonia

“Behind-the-Table” Conflicts in the Failed Negotiation for a Referendum for the Independence of Catalonia Oriol Valentí i Vidal*∗ Spain is facing its most profound constitutional crisis since democracy was restored in 1978. After years of escalating political conflict, the Catalan government announced it would organize an independence referendum on October 1, 2017, an outcome that the Spanish government vowed to block. This article represents, to the best of the author’s knowledge, the first scholarly examination to date from a negotiation theory perspective of the events that hindered political dialogue between both governments regarding the organization of the secession vote. It applies Robert H. Mnookin’s insights on internal conflicts to identify the apparent paradox that characterized this conflict: while it was arguably in the best interest of most Catalans and Spaniards to know the nature and extent of the political relationship that Catalonia desired with Spain, their governments were nevertheless unable to negotiate the terms and conditions of a legal, mutually agreed upon referendum to achieve this result. This article will argue that one possible explanation for this paradox lies in the “behind-the-table” *Attorney; Lecturer in Law, Barcelona School of Management (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) as of February 2018. LL.M. ‘17, Harvard Law School; B.B.A. ‘13 and LL.B. ‘11, Universitat Pompeu Fabra; Diploma in Legal Studies ‘10, University of Oxford. This article reflects my own personal views and has been written under my sole responsibility. As such, it has not been written under the instructions of any professional or academic organization in which I render my services.