Kindergarten Tribal History Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curiosity's Candidate Field Site in Gale Crater, Mars

Curiosity’s Candidate Field Site in Gale Crater, Mars K. S. Edgett – 27 September 2010 Simulated view from Curiosity rover in landing ellipse looking toward the field area in Gale; made using MRO CTX stereopair images; no vertical exaggeration. The mound is ~15 km away 4th MSL Landing Site Workshop, 27–29 September 2010 in this view. Note that one would see Gale’s SW wall in the distant background if this were Edgett, 1 actually taken by the Mastcams on Mars. Gale Presents Perhaps the Thickest and Most Diverse Exposed Stratigraphic Section on Mars • Gale’s Mound appears to present the thickest and most diverse exposed stratigraphic section on Mars that we can hope access in this decade. • Mound has ~5 km of stratified rock. (That’s 3 miles!) • There is no evidence that volcanism ever occurred in Gale. • Mound materials were deposited as sediment. • Diverse materials are present. • Diverse events are recorded. – Episodes of sedimentation and lithification and diagenesis. – Episodes of erosion, transport, and re-deposition of mound materials. 4th MSL Landing Site Workshop, 27–29 September 2010 Edgett, 2 Gale is at ~5°S on the “north-south dichotomy boundary” in the Aeolis and Nepenthes Mensae Region base map made by MSSS for National Geographic (February 2001); from MOC wide angle images and MOLA topography 4th MSL Landing Site Workshop, 27–29 September 2010 Edgett, 3 Proposed MSL Field Site In Gale Crater Landing ellipse - very low elevation (–4.5 km) - shown here as 25 x 20 km - alluvium from crater walls - drive to mound Anderson & Bell -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

Click Here to Download the 4Th Grade Curriculum

Copyright © 2014 The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. All rights reserved. All materials in this curriculum are copyrighted as designated. Any republication, retransmission, reproduction, or sale of all or part of this curriculum is prohibited. Introduction Welcome to the Grand Ronde Tribal History curriculum unit. We are thankful that you are taking the time to learn and teach this curriculum to your class. This unit has truly been a journey. It began as a pilot project in the fall of 2013 that was brought about by the need in Oregon schools for historically accurate and culturally relevant curriculum about Oregon Native Americans and as a response to countless requests from Oregon teachers for classroom- ready materials on Native Americans. The process of creating the curriculum was a Tribal wide effort. It involved the Tribe’s Education Department, Tribal Library, Land and Culture Department, Public Affairs, and other Tribal staff. The project would not have been possible without the support and direction of the Tribal Council. As the creation was taking place the Willamina School District agreed to serve as a partner in the project and allow their fourth grade teachers to pilot it during the 2013-2014 academic year. It was also piloted by one teacher from the Pleasant Hill School District. Once teachers began implementing the curriculum, feedback was received regarding the effectiveness of lesson delivery and revisions were made accordingly. The teachers allowed Tribal staff to visit during the lessons to observe how students responded to the curriculum design and worked after school to brainstorm new strategies for the lessons and provide insight from the classroom teacher perspective. -

By the Numbers

By the Numbers Quantifying Some of Our Environmental & Social Work 6.2 MILLION 100 Dollars we donated this fiscal year Percentage of Patagonia products we take to fund environmental work back for recycling 70 MILLION 164,062 Cash and in-kind services we’ve donated since Pounds of Patagonia products recycled our tithing program began in 1985 or upcycled since 2004 741 84 Environmental groups that received Percentage of water saved through our new a Patagonia grant this year denim dyeing technology as compared to environmental + social initiatives conventional synthetic indigo denim dyeing 116,905 Dollars given to nonprofits this year through 100 our Employee Charity Match program Percentage of Traceable Down (traceable to birds that were never live-plucked, 20 MILLION & CHANGE never force-fed) we use in our down products 2 Dollars we’ve allocated to invest in environmentally and socially responsible companies through our 1996 venture capital fund Year we switched to the exclusive use of organically grown cotton 0 8 New investments we made this year through 10,424 $20 Million & Change Hours our employees volunteered this year 1 on the company dime 5 Mega-dams that will not be built on Chile’s Baker 30,000 and Pascua rivers thanks to a worldwide effort Approximate number of Patagonia products 5 in which we participated repaired this year at our Reno Service Center 380 15 MILLION Public screenings this year for DamNation Acres of degraded grassland we hope to restore in the Patagonia region of South America by buying and supporting the purchase of responsibly sourced 75,000 merino wool Signatures collected this year petitioning the Obama administration to remove four dams initiatives social + environmental on the lower Snake River 774,671 Single-driver car-trip miles avoided this year 192 through our Drive-Less program Fair Trade Certified™ styles in the Patagonia line as of fall 2015 100 MILLION Dollars 1% for the Planet® has donated to nonprofit environmental groups cover: Donnie Hedden © 2015 Patagonia, Inc. -

Indian Country Welcome To

Travel Guide To OREGON Indian Country Welcome to OREGON Indian Country he members of Oregon’s nine federally recognized Ttribes and Travel Oregon invite you to explore our diverse cultures in what is today the state of Oregon. Hundreds of centuries before Lewis & Clark laid eyes on the Pacific Ocean, native peoples lived here – they explored; hunted, gathered and fished; passed along the ancestral ways and observed the ancient rites. The many tribes that once called this land home developed distinct lifestyles and traditions that were passed down generation to generation. Today these traditions are still practiced by our people, and visitors have a special opportunity to experience our unique cultures and distinct histories – a rare glimpse of ancient civilizations that have survived since the beginning of time. You’ll also discover that our rich heritage is being honored alongside new enterprises and technologies that will carry our people forward for centuries to come. The following pages highlight a few of the many attractions available on and around our tribal centers. We encourage you to visit our award-winning native museums and heritage centers and to experience our powwows and cultural events. (You can learn more about scheduled powwows at www.traveloregon.com/powwow.) We hope you’ll also take time to appreciate the natural wonders that make Oregon such an enchanting place to visit – the same mountains, coastline, rivers and valleys that have always provided for our people. Few places in the world offer such a diversity of landscapes, wildlife and culture within such a short drive. Many visitors may choose to visit all nine of Oregon’s federally recognized tribes. -

Tribal Members Come out to Make Idle No More Rally Happen

Vol. XXVII, Issue 1 Hu\c wiconi\ na\ wira | First Bear Moon January 18, 2013 Ho-Chunk Nation IMPORTANT INFORMATION Housing Survey US Mailing on Cobell Settlements Kickapoo Valley Winter Festival Return by February 1, 2013 Page 8 Page6 Page 13 Tribal members come out to make Idle No More rally happen U.K., and Germany. the capitol building. The Madison Idle No More The Idle No More Solidarity Peace Rally was movement wouldn’t be where held on a Sunday afternoon in it’s at without Facebook and cold temperatures. The rally YouTube. One blogger at the was organized with the help Madison event said once she of Ho-Chunk tribal members uploads her videos, they go Arvina Martin and Sanford worldwide. You can see many Littleeagle. They organized of the Idle No More events speakers and drums. The rally on YouTube, and if you want featured the Overpass Light to attend, Facebook is full of Brigade, a group who grew events. out of the effort to Recall Funmaker shared his Wisconsin Governor Scott thought about the Madison Walker and have been helping event in a Facebook post: people promote their causes “Idle No More Madison was with their lighted messages. pretty good. That sign “Honor It also featured a the Treaties” burned a lasting couple Ho-Chunk tribal image in my mind. There Ho-Chunk tribal members, Phyllis Smoke and her daughter Tori Cleveland, hold members who spoke to the were so many good things the Idle No More banner masses: Forrest Funmaker that happened that day. It was and Wilfrid Cleveland. -

El $U D'europa

nedacerd 1 artinintairien), ...toa ea Grecia. 54.— T'Un» 1451-5 Tener' eltunrernta. ig-b8 eä . ea... 11 13.— toübfon 1318-4 MEUS DE SUBSCRIPCIÓ: '..-- ED/C10 DIARIA erreiona Pri. alee pmestna inerte& , 7150 " trimeates -7: mnerIca 1111111. 850 • • aatet,o . Ab • • i ' LA CRI151 FI/Aligera:U' la- • Lisa Olurn I 1.1114 tuff XLVII. — NUM. r-. ANY 16,129.— PREU: 10 CENTIMS BARCELONA, DIUMENGE, 29 DE NOVEMBRE DE 1925 . IIIIIIiil8ll1H11111111111111111411iiiiiMliniff,i,1 ninimigiemilummiiiire EL DE FRANÇA CARTES DE LONDRES $ U D'EUROPA M. Briand constitueix ministeri C1) 3IBIE Clb El pacte de Locarno tindrà, aegurament, efectes sedants — — ere el conjunt d'Europa. Briand té l'esperança de "locar- (DEL NOSTRE REDACTOR-CORRESPONSJ ;lazar", As a dir, de portar l'esperit de Locarno als altres pro- La llista del nou Govern blemes internacionals d'Europa, mitjançant pactes similars. Londres. novembre. • astronúmic. Total: quan den- Sens dubte hi ha motius per a les esperances. Per?) no tot són Entren en el Ministeri els partits radical-socialista, republicà-socialista, de l'es- colirseixu per un carrer una su- esperances en el cel d'Europa. La realitat ens ha dut, aquests .fa esta entes: els anglesos eursal guerra radical, republicà d'esquerra i de l'esquerra sap dem trust Lyons. Pis ca- dies mateix, la visió d'algunes espumes de perill. I potser el democràtica : Tornant de Lon- sen Pelee no se frns bolle se'm posen de punta. motiu més important d'inquietud és la possible acció exterior dres, M. Briand redactarà la declaració a quin grau porten els anglesos Aquesta intromissid 4o la hei ministerial el sen inegisme fina que 3'hpn e[ cha de demà — marxista do la rete-entrad-id del que un demà més o menys pròxim—pui uns dies a- Anglaterea. -

Instrumental Methods for Professional and Amateur

Instrumental Methods for Professional and Amateur Collaborations in Planetary Astronomy Olivier Mousis, Ricardo Hueso, Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Sylvain Bouley, Benoît Carry, Francois Colas, Alain Klotz, Christophe Pellier, Jean-Marc Petit, Philippe Rousselot, et al. To cite this version: Olivier Mousis, Ricardo Hueso, Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Sylvain Bouley, Benoît Carry, et al.. Instru- mental Methods for Professional and Amateur Collaborations in Planetary Astronomy. Experimental Astronomy, Springer Link, 2014, 38 (1-2), pp.91-191. 10.1007/s10686-014-9379-0. hal-00833466 HAL Id: hal-00833466 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00833466 Submitted on 3 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Instrumental Methods for Professional and Amateur Collaborations in Planetary Astronomy O. Mousis, R. Hueso, J.-P. Beaulieu, S. Bouley, B. Carry, F. Colas, A. Klotz, C. Pellier, J.-M. Petit, P. Rousselot, M. Ali-Dib, W. Beisker, M. Birlan, C. Buil, A. Delsanti, E. Frappa, H. B. Hammel, A.-C. Levasseur-Regourd, G. S. Orton, A. Sanchez-Lavega,´ A. Santerne, P. Tanga, J. Vaubaillon, B. Zanda, D. Baratoux, T. Bohm,¨ V. Boudon, A. Bouquet, L. Buzzi, J.-L. Dauvergne, A. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

KLAMATH NEWS the Indicator Species

Page 1, Klamath News 2010 KLAMATH NEWS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE KLAMATH TRIBES: KLAMATH, MODOC, AND YAHOOSKIN TREATY OF 1864 Winema Charley Mogenkaskit Lalo Schonchin Captain Jack Volume 35, Issue 1 The Klamath Tribes, P.O. Box 436, Chiloquin, OR 97624 1ST QTR. ISSUE 2019 1-800-524-9787 or (541) 783-2219 Website: www.klamathtribes.org JANUARY-MARCH Tucked away in a corner of Oregon... There is a Tribe, With extraordinary people... Doing monumental work to Save an Indigenous Species from Extinction! Nowhere else in the World (The c'waam) - The Lost River Sucker The Cleaner's of the Water ... If the fish die, the People Die. The Indicator Species THE KLAMATH TRIBES AQUATICS PROGRAM The Klamath Tribes P.O. Box 436 PRESORTED FIRST-CLASS MAIL Chiloquin, OR 97624 The Klamath Tribes Aquatic Program is within the Natural Resources U.S. POSTAGE PAID Department and employs 18 permanent staff and a few seasonal in- CHILOQUIN, OR terns and temporary workers. The program is housed at the Research ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED PERMIT NO. 4 Station located four miles east of Chiloquin, Oregon at the historic Braymill site. In 1988, the Research Station began as a small research hatchery and fish rearing ponds located across the road from the cur- rent Research Station along the Sprague River. At that time, the entire Natural Resources Program included only five full time employees including Don Gentry, Craig Bienz, Jacob Kann, Larry Dunsmoor, Elwood (Cisco) Miller, and a couple of seasonal technicians. Currently, the Research Station consists of two large buildings and parking lot. -

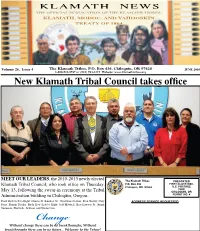

Change There Can Be No Breakthroughs, Without Breakthroughs There Changecan Be No Future

Page 1, Klamath News 2010 KLAMATH NEWS THE OFFICIAL Publication OF THE KLAMath TRIBES: KLAMath, MODOC, AND YAHOOSKIN Treaty OF 1864 Winema Charley Mogenkaskit Lalo Schonchin Captain Jack Volume 26, Issue 4 The Klamath Tribes, P.O. Box 436, Chiloquin, OR 97624 JUNE 2010 1-800-524-9787 or (541) 783-2219 Website: www.klamathtribes.org New Klamath Tribal Council takes office MEET OUR LEADERS , the 2010-2013 newly elected The Klamath Tribes PRESORTED Klamath Tribal Council, who took office on Thursday, P.O. Box 436 FIRST-CLASS MAIL Chiloquin, OR 97624 U.S. POSTAGE PAID May 13, following the swear-in ceremony at the Tribal CHILOQUIN, OR Administration building in Chiloquin, Oregon. PERMIT NO. 4 Front Row Left to Right: Charles E. Kimbol, Sr., GeorGene Nelson, Don Gentry, Gary ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED Frost, Brandi Decker. Back Row Left to Right: Jeff Mitchell, Bert Lawvor Sr., Frank Summers, Shawn L. Jackson, and Torina Case. Without change there can be no breakthroughs, Without breakthroughs there Changecan be no future... Welcome to the Future! Page 2, Klamath News 2010 The Klamath News is a Tribal Government Publication of the Swear-in Ceremony for Tribal Council Klamath Tribes, (the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Band of Snake Indians). * Distribution: Publications are distributed at the end of the month, or as fund- ing allows. * Deadline: Information submitted for publication must be received by the 15th of each month- (for the following month’s publication). * Submissions: Submissions should be typed and not exceed 500 words. Submissions must include the author’s signature, address and phone number.