View the Klamath Summary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

Nesting Populations of California and Ring-Billed Gulls in California

WESTERN BIR Volume 31, Number 3, 2000 NESTING POPULATIONS OF CLwO AND RING-BI--F-r GULLS IN CALIFORNIA: RECENT SURVEYS AND HISTORICAL STATUS W. DAVID SHUFORD, Point Reyes Bird Observatory(PRBO), 4990 Shoreline Highway, StinsonBeach, California94970 THOMAS P. RYAN, San FranciscoBay Bird Observatory(SFBBO), P.O. Box 247, 1290 Hope Street,Alviso, California 95002 ABSTRACT: Statewidesurveys from 1994 to 1997 revealed33,125 to 39,678 breedingpairs of CaliforniaGulls and at least9611 to 12,660 pairsof Ring-billed Gullsin California.Gulls nested at 12 inland sitesand in San FranciscoBay. The Mono Lake colonywas by far the largestof the CaliforniaGull, holding 70% to 80% of the statepopulation, followed by SanFrancisco Bay with 11% to 14%. ButteValley WildlifeArea, Clear Lake NationalWildlife Refuge, and Honey Lake WildlifeArea were the only othersites that heldover 1000 pairsof CaliforniaGulls. In mostyears, Butte Valley, Clear Lake, Big Sage Reservoir,and Honey Lake togetherheld over 98% of the state'sbreeding Ring-billed Gulls; Goose Lake held9% in 1997. Muchof the historicalrecord of gullcolonies consists of estimatestoo roughfor assessmentof populationtrends. Nevertheless, California Gulls, at least,have increased substantially in recentdecades, driven largely by trendsat Mono Lake and San FranciscoBay (first colonizedin 1980). Irregularoccupancy of some locationsreflects the changing suitabilityof nestingsites with fluctuatingwater levels.In 1994, low water at six sites allowedcoyotes access to nestingcolonies, and resultingpredation appeared to reducenesting success greatly at threesites. Nesting islands secure from predators and humandisturbance are nestinggulls' greatest need. Conover(1983) compileddata suggestingthat breedingpopulations of Ring-billed(Larus delawarensis)and California(Larus californicus)gulls haveincreased greafiy in the Westin recentdecades. Detailed assessments of populationstatus and trends of these speciesin individualwestern states, however,have been publishedonly for Washington(Conover et al. -

Volcanic Legacy

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacifi c Southwest Region VOLCANIC LEGACY March 2012 SCENIC BYWAY ALL AMERICAN ROAD Interpretive Plan For portions through Lassen National Forest, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Tule Lake, Lava Beds National Monument and World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................4 Background Information ........................................................................................................................4 Management Opportunities ....................................................................................................................5 Planning Assumptions .............................................................................................................................6 BYWAY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ......................................................................................................7 Management Goals ..................................................................................................................................7 Management Objectives ..........................................................................................................................7 Visitor Experience Goals ........................................................................................................................7 Visitor -

Indian Country Welcome To

Travel Guide To OREGON Indian Country Welcome to OREGON Indian Country he members of Oregon’s nine federally recognized Ttribes and Travel Oregon invite you to explore our diverse cultures in what is today the state of Oregon. Hundreds of centuries before Lewis & Clark laid eyes on the Pacific Ocean, native peoples lived here – they explored; hunted, gathered and fished; passed along the ancestral ways and observed the ancient rites. The many tribes that once called this land home developed distinct lifestyles and traditions that were passed down generation to generation. Today these traditions are still practiced by our people, and visitors have a special opportunity to experience our unique cultures and distinct histories – a rare glimpse of ancient civilizations that have survived since the beginning of time. You’ll also discover that our rich heritage is being honored alongside new enterprises and technologies that will carry our people forward for centuries to come. The following pages highlight a few of the many attractions available on and around our tribal centers. We encourage you to visit our award-winning native museums and heritage centers and to experience our powwows and cultural events. (You can learn more about scheduled powwows at www.traveloregon.com/powwow.) We hope you’ll also take time to appreciate the natural wonders that make Oregon such an enchanting place to visit – the same mountains, coastline, rivers and valleys that have always provided for our people. Few places in the world offer such a diversity of landscapes, wildlife and culture within such a short drive. Many visitors may choose to visit all nine of Oregon’s federally recognized tribes. -

KLAMATH HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT [FERC No

KLAMATH HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT [FERC No. 2082] REQUEST FOR DETERMINATION OF ELIGIBILITY Copco No. 1, c1915 PacifiCorp Archives Photo for PacifiCorp, Portland, OR Prepared by George Kramer, M.S., HP Preservation Specialist Under contract to CH2M-Hill Corvallis, OR October 2003 App E-6E DOE 1_Cover.doc DETERMINATION OF ELIGIBILITY FOR THE NATIONAL REGISTER Property Name: KLAMATH HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT Date of Construction: 1903-1958 Address: N/A County: Klamath, Oregon Siskiyou, California Original Use: Hydroelectric Generation Current Use: Hydroelectric Generation Style: Utilitarian/Industrial Theme: Commerce/Industrial _____________________________________________________________________________________ PRIMARY SIGNIFICANCE: The resources of the Klamath Hydroelectric Project were built between 1903 and 1958 by the California Oregon Power Company and its various pioneer predecessors and are now owned and operated by PacifiCorp under Federal Energy Regulatory License No. 2082. The resources of the project are strongly associated with the early development of electricity in the southern Oregon and northern California region and played a significant role in the area’s economy both directly, as a part of a regionally-significant, locally-owned and operated, private utility, and indirectly, through the role that increased electrical capacity played in the expansion of the timber, agriculture, and recreation industries during the first six decades of the 20th century. The Klamath Hydroelectric Project is considered regionally significant and eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion “A” for its association with the industrial and economic development of southern Oregon and northern California. [See Statement of Significance, Page 19] Copco No. 1, Dam and Gatehouse, 2002 In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the criteria for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. -

Relative Dating and the Rock Art of Lava Beds National Monument

RELATIVE DATING AND THE ROCK ART OF LAVA BEDS NATIONAL MONUMENT Georgia Lee and William D. Hyder University of California, Los Angeles University of California, Santa Barbara ABSTRACT Dating rock art has long been a serious impediment to its use in archaeological research. Two rock art sites in Lava Beds National Monument present an unusual opportunity for the establishment of a relative dating scheme tied to external environmental events. In the case of Petroglyph Point, extended wet and dry climatic cycles produced changes in the levels of Tule Lake that successively covered, eroded, and then exposed the petroglyph bearing surfaces. Similarly, wet periods would have precluded painting at the nearby Fern Cave as the cave walls would have been too wet for paint to bond to the wall. The study of past climatic conditions, coupled with other archaeological evidence, allows us to present a model from which a relative chronology for Modoc rock art of Northeastern California covering the past 5,000 years can be constructed. INTRODUCTION Lava Beds National Monument is located in northeastern California, south of Klamath Falls, Oregon. Aside from a very interesting history that encompasses the Modoc Indians (and their predecessors) and the famous Modoc Wars of 1872-73, the Monument has numerous natural geological features of interest, as well as some outstanding rock art sites. It is also on the migratory bird flyway, making it a popular area for hunters and bird watchers alike. During World War II a Japanese internment camp was located nearby. These various attractions serve to draw a number of visitors to the Monument throughout the year. -

Tenth Western Black Bear Workshop

PROCEEDINGS of the TENTH WESTERN BLACK BEAR WORKSHOP The Changing Climate for Bear Conservation and Management in Western North America Lake Tahoe, Nevada Image courtesy of Reno Convention and Visitors Authority 18-22 May 2009 Peppermill Resort, Reno, Nevada Hosted by The Nevada Department of Wildlife A WAFWA Sanctioned Event Carl W. Lackey and Richard A. Beausoleil, Editors PROCEEDINGS OF THE TENTH WESTERN BLACK BEAR WORKSHOP 18-22 May 2009 Peppermill Resort, Reno, Nevada Hosted by Nevada Department of Wildlife A WAFWA Sanctioned Event Carl W. Lackey & Richard A. Beausoleil Editors International Association for Bear Research and Management SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR WORKSHOP SPONSORS International Association for Bear Research & Management Wildlife Conservation Society Nevada Wildlife Record Book Nevada Bighorns Unlimited - Reno Nevada Department of Wildlife Carson Valley Chukar Club U.S. Forest Service – Carson Ranger District Safari Club International University of Nevada, Reno - Cast & Blast Outdoors Club Berryman Institute Suggested Citation: Author’s name(s). 2010. Title of article or abstract. Pages 00-00 in C. Lackey and R. A. Beausoleil, editors, Western Black Bear Workshop 10:__-__. Nevada Department of Wildlife 1100 Valley Road Reno, NV 89512 Information on how to order additional copies of this volume or other volumes in this series, as well as volumes of Ursus, the official publication of the International Association for Bear Research and Management, may be obtained from the IBA web site: www.bearbiology.com, from the IBA newsletter International Bear News, or from Terry D. White, University of Tennessee, Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries, P.O. Box 1071, Knoxville, TN 37901-1071, USA. -

Health and Well-Being: Federal Indian Policy, Klamath Women, And

Health and Well-being Federal Indian Policy, Klamath Women, and Childbirth CHRISTIN HANCOCK AS SCHOLARS OF CHILDBIRTH have pointed out, “birth” is always more than a mere biological event.1 It is inherently a social process as well, one that is shaped by cultural norms and power structures that are both raced and classed. For Native American women, the historical experiences of birth have been shaped by the larger context of settler colonialism.2 Despite this reality, very little attention has been paid by historians of childbirth to the ways that Native women’s experiences are bound up in this broader ten- sion between assimilation and resistance to dominant colonial structures. Similarly, few historians of American Indians have focused their attention specifically on birth.3 And yet birth is inherently tied to our beliefs about, as well as our experiences and practices of, health and health care. Always, the regulation and practice of birth is also about the regulation and practice of health. What constitutes health? Who defines “good” health? And who has access to it? As reproductive justice scholar Barbara Gurr has noted, social and political forces must be considered in any attempts at answering these questions for marginalized women. One cannot explore the history of Native women’s experiences of childbirth without also engaging in a larger history of the ways that their health and health care have been defined and shaped by federal Indian policies. Gurr argues that such an approach is “particularly relevant to many Native American women, whose group identity has been historically targeted for removal and assimilation by the U.S. -

KLAMATH NEWS the Indicator Species

Page 1, Klamath News 2010 KLAMATH NEWS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE KLAMATH TRIBES: KLAMATH, MODOC, AND YAHOOSKIN TREATY OF 1864 Winema Charley Mogenkaskit Lalo Schonchin Captain Jack Volume 35, Issue 1 The Klamath Tribes, P.O. Box 436, Chiloquin, OR 97624 1ST QTR. ISSUE 2019 1-800-524-9787 or (541) 783-2219 Website: www.klamathtribes.org JANUARY-MARCH Tucked away in a corner of Oregon... There is a Tribe, With extraordinary people... Doing monumental work to Save an Indigenous Species from Extinction! Nowhere else in the World (The c'waam) - The Lost River Sucker The Cleaner's of the Water ... If the fish die, the People Die. The Indicator Species THE KLAMATH TRIBES AQUATICS PROGRAM The Klamath Tribes P.O. Box 436 PRESORTED FIRST-CLASS MAIL Chiloquin, OR 97624 The Klamath Tribes Aquatic Program is within the Natural Resources U.S. POSTAGE PAID Department and employs 18 permanent staff and a few seasonal in- CHILOQUIN, OR terns and temporary workers. The program is housed at the Research ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED PERMIT NO. 4 Station located four miles east of Chiloquin, Oregon at the historic Braymill site. In 1988, the Research Station began as a small research hatchery and fish rearing ponds located across the road from the cur- rent Research Station along the Sprague River. At that time, the entire Natural Resources Program included only five full time employees including Don Gentry, Craig Bienz, Jacob Kann, Larry Dunsmoor, Elwood (Cisco) Miller, and a couple of seasonal technicians. Currently, the Research Station consists of two large buildings and parking lot. -

Change There Can Be No Breakthroughs, Without Breakthroughs There Changecan Be No Future

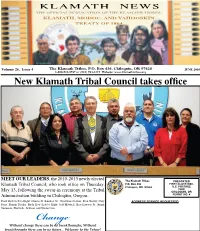

Page 1, Klamath News 2010 KLAMATH NEWS THE OFFICIAL Publication OF THE KLAMath TRIBES: KLAMath, MODOC, AND YAHOOSKIN Treaty OF 1864 Winema Charley Mogenkaskit Lalo Schonchin Captain Jack Volume 26, Issue 4 The Klamath Tribes, P.O. Box 436, Chiloquin, OR 97624 JUNE 2010 1-800-524-9787 or (541) 783-2219 Website: www.klamathtribes.org New Klamath Tribal Council takes office MEET OUR LEADERS , the 2010-2013 newly elected The Klamath Tribes PRESORTED Klamath Tribal Council, who took office on Thursday, P.O. Box 436 FIRST-CLASS MAIL Chiloquin, OR 97624 U.S. POSTAGE PAID May 13, following the swear-in ceremony at the Tribal CHILOQUIN, OR Administration building in Chiloquin, Oregon. PERMIT NO. 4 Front Row Left to Right: Charles E. Kimbol, Sr., GeorGene Nelson, Don Gentry, Gary ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED Frost, Brandi Decker. Back Row Left to Right: Jeff Mitchell, Bert Lawvor Sr., Frank Summers, Shawn L. Jackson, and Torina Case. Without change there can be no breakthroughs, Without breakthroughs there Changecan be no future... Welcome to the Future! Page 2, Klamath News 2010 The Klamath News is a Tribal Government Publication of the Swear-in Ceremony for Tribal Council Klamath Tribes, (the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Band of Snake Indians). * Distribution: Publications are distributed at the end of the month, or as fund- ing allows. * Deadline: Information submitted for publication must be received by the 15th of each month- (for the following month’s publication). * Submissions: Submissions should be typed and not exceed 500 words. Submissions must include the author’s signature, address and phone number. -

Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for Breeding Western and Clark’S Grebes in California

Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for Breeding Western and Clark’s Grebes in California Gary L. Ivey, Wildlife Consultant PO Box 2213 Corvallis, OR 97339-2213 [email protected] June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES.............................................................................................. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...........................................................................................................vii INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................2 Taxonomy ...............................................................................................................................2 Legal status .............................................................................................................................2 Description..............................................................................................................................2 Geographic distribution ..........................................................................................................3 Life history .............................................................................................................................5 -

The Art of Ceremony: Regalia of Native Oregon

The Art of Ceremony: Regalia of Native Oregon September 28, 2008 – January 18, 2009 Hallie Ford Museum of Art Willamette University Teachers Guide This guide is to help teachers prepare students for a field trip to the exhibition, The Art of Ceremony: Regalia of Native Oregon and offer ideas for leading self-guided groups through the galleries. Teachers, however, will need to consider the level and needs of their students in adapting these materials and lessons. Goals • To introduce students to the history and culture of Oregon’s nine federally recognized tribal communities • To introduce students to the life ways, traditions, rituals and ceremonies of each of the nine tribal communities through their art and art forms (ancient techniques, materials, preparation, and cultural guidelines and practices) • To understand the relevance of continuity to a culture Objectives Students will be able to • Discuss works of art and different art forms in relation to the history and culture of Oregon’s nine federally recognized tribal communities • Discuss various traditional art forms as reflected in the objects and performances represented in the exhibition • Identify a number of traditional techniques, including weaving, beadwork and carving • Discuss tradition and renewal in the art forms of the nine tribal communities and their relationship to the life ways, traditions and rituals of the communities • Make connections to other disciplines Preparing for the tour: • If possible, visit the exhibition on your own beforehand. • Using the images (print out transparencies or sets for students, create a bulletin board, etc.) and information in the teacher packet, create a pre-tour lesson plan for the classroom to support and complement the gallery experience.