The American and Japanese Navies As Hypothetical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

Tactics Are for Losers

Tactics are for Losers Military Education, The Decline of Rational Debate and the Failure of Strategic Thinking in the Imperial Japanese Navy: 1920-1941 A submission for the 2019 CN Essay Competition For Entry in the OPEN and DEFENCE Divisions The period of intense mechanisation and modernisation that affected all of the world’s navies during the latter half of the 19th and first half of the 20th century had possibly its greatest impact in the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). Having been shocked into self- consciousness concerning their own vulnerability to modern firepower by the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry’s ‘Black Fleet’ at Edo bay on 8 July 1853, the state of Japan launched itself onto a trajectory of rapid modernisation. Between 1863 and 1920, the Japanese state transformed itself from a forgotten backwater of the medieval world to one of the world’s great technological and industrialised powers. The spearhead of this meteoric rise from obscurity to great power status in just over a half-century was undoubtedly the Imperial Japanese Navy, which by 1923 was universally recognised during the Washington Naval Conference as the world’s third largest and most powerful maritime force.1 Yet, despite the giant technological leaps forward made by the Imperial Japanese Navy during this period, the story of Japan’s and the IJN’s rise to great power status ends in 1945 much as it began during the Perry expedition; with an impotent government being forced to bend to the will of the United States and her allies while a fleet of foreign warships rested at anchor in Tokyo Bay. -

Theodore Roosevelt's Big-Stick Policy

THEODORE ROOSEVELT'S BIG-STICK POLICY - In 1901, only a few months after being inaugurated president for a second time, McKinley was killed by an anarchist - Succeeding him was the vice president-the young expansionist and hero of the Spanish-American War, Theodore Roosevelt - Describing his foreign policy, the new president had once said that it was his motto to "speak softly and carry a big stick" - The press therefore applied the label "big stick" to Roosevelt's aggressive foreign policy - By acting decisively in a number of situations, Roosevelt attempted to build the reputation of the U.S. as a world power - Imperialists liked him, but critics of the big-stick policy disliked breaking from the tradition of noninvolvement in global politics THE PANAMA CANAL - As a result of the Spanish-American War, the new American empire stretched from Puerto Rico to the Philippines in the Pacific - As a strategy for holding these islands, the U.S. needed a canal in Central America to connect the Atlantic & Pacific Oceans REVOLUTION IN PANAMA - Roosevelt was eager to begin the construction of a canal through the narrow but rugged terrain of the isthmus of Panama - He was frustrated that Colombia controlled Panama & refused to agree to U.S. terms for digging the canal through Panama - Losing patience with Colombia, Roosevelt supported a revolt in Panama in 1903 - With U.S. backing, the rebellion succeeded immediately and almost without bloodshed - The first act of the new gov't of independent Panama was to sign a treaty (the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty of 1903) granting the U.S. -

Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES CSC 28 / CCEM 28 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES (MDS) THESIS THE CORVETTE - A SHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY CANADIAN NAVY LA CORVETTE - UN NAVIRE POUR LA MARINE CANADIENNE DU 21E SIÈCLE By/par LCdr/capc Pierre Bédard This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un stagiaire the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of one du Collège des Forces canadiennes pour of the requirements of the Course of Studies. satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. The paper is a scholastic document, and thus L'étude est un document qui se rapporte au contains facts and opinions, which the author cours et contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and correct for que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et the subject. -

The Insular Cases: the Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid

ARTICLES THE INSULAR CASES: THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A REGIME OF POLITICAL APARTHEID BY JUAN R. TORRUELLA* What's in a name?' TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 284 2. SETFING THE STAGE FOR THE INSULAR CASES ........................... 287 2.1. The Historical Context ......................................................... 287 2.2. The A cademic Debate ........................................................... 291 2.3. A Change of Venue: The Political Scenario......................... 296 3. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ............................................ 300 4. THE PROGENY OF THE INSULAR CASES ...................................... 312 4.1. The FurtherApplication of the IncorporationTheory .......... 312 4.2. The Extension of the IncorporationDoctrine: Balzac v. P orto R ico ............................................................................. 317 4.2.1. The Jones Act and the Grantingof U.S. Citizenship to Puerto Ricans ........................................... 317 4.2.2. Chief Justice Taft Enters the Scene ............................. 320 * Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. This article is based on remarks delivered at the University of Virginia School of Law Colloquium: American Colonialism: Citizenship, Membership, and the Insular Cases (Mar. 28, 2007) (recording available at http://www.law.virginia.edu/html/ news/2007.spr/insular.htm?type=feed). I would like to recognize the assistance of my law clerks, Kimberly Blizzard, Adam Brenneman, M6nica Folch, Tom Walsh, Kimberly Sdnchez, Anne Lee, Zaid Zaid, and James Bischoff, who provided research and editorial assistance. I would also like to recognize the editorial assistance and moral support of my wife, Judith Wirt, in this endeavor. 1 "What's in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet." WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, ROMEO AND JULIET act 2, sc. 1 (Richard Hosley ed., Yale Univ. -

The Square Deal

Teddy Roosevelt - The Trust Buster Teddy Roosevelt was one American who believed a revolution was coming. He believed Wall Street financiers and powerful trust titans to be acting foolishly. He believed that large trusts and monopolies were harmful to the economy and especially to the consumer. While they were eating off fancy china on mahogany tables in marble dining rooms, the masses were roughing it. There seemed to be no limit to greed. If docking wages would increase profits, it was done. If higher railroad rates put more gold in their coffers, it was done. How much was enough, Roosevelt wondered? The President's weapon was the Sherman Antitrust Act, passed by Congress in 1890. This law declared illegal all combinations "in restraint of trade." For the first twelve years of its existence, the Sherman Act was a paper tiger. United States courts routinely sided with business when any enforcement of the Act was attempted. 1. What belief guided President Theodore Roosevelt’s efforts as a trustbuster? 2. What is a monopoly? Why are they harmful to the economy and to the consumer? 3. What piece of legislation did Roosevelt use to break up monopolies? The Square Deal The Square Deal was Roosevelt's domestic program formed on three basic ideas: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection. In general, the Square Deal attacked plutocracy and bad trusts while simultaneously protecting businesses from the most extreme demands of organized labor. In contrast to his predecessor William McKinley, Roosevelt believed that such government action was necessary to mitigate social evil, and as president denounced “the representatives of predatory wealth” as guilty of “all forms of iniquity from the oppression of wage workers to defrauding the public." Trusts and monopolies became the primary target of Square Deal legislation. -

Whose History and by Whom: an Analysis of the History of Taiwan In

WHOSE HISTORY AND BY WHOM: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORY OF TAIWAN IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE PUBLISHED IN THE POSTWAR ERA by LIN-MIAO LU (Under the Direction of Joel Taxel) ABSTRACT Guided by the tenet of sociology of school knowledge, this study examines 38 Taiwanese children’s trade books that share an overarching theme of the history of Taiwan published after World War II to uncover whether the seemingly innocent texts for children convey particular messages, perspectives, and ideologies selected, preserved, and perpetuated by particular groups of people at specific historical time periods. By adopting the concept of selective tradition and theories of ideology and hegemony along with the analytic strategies of constant comparative analysis and iconography, the written texts and visual images of the children’s literature are relationally analyzed to determine what aspects of the history and whose ideologies and perspectives were selected (or neglected) and distributed in the literary format. Central to this analysis is the investigation and analysis of the interrelations between literary content and the issue of power. Closely related to the discussion of ideological peculiarities, historians’ research on the development of Taiwanese historiography also is considered in order to examine and analyze whether the literary products fall into two paradigms: the Chinese-centric paradigm (Chinese-centricism) and the Taiwanese-centric paradigm (Taiwanese-centricism). Analysis suggests a power-and-knowledge nexus that reflects contemporary ruling groups’ control in the domain of children’s narratives in which subordinate groups’ perspectives are minimalized, whereas powerful groups’ assumptions and beliefs prevail and are perpetuated as legitimized knowledge in society. -

Command: a Historical Perspective

2020, VOLUME 3 NUMBER 1 AN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES COMMAND: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Rear Admiral (Ret) James Goldrick Royal Austrailian Navy CENTER FOR CHARACTER & LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT EDITORIAL STAFF: EDITORIAL BOARD: Dr. Mark Anarumo, Dr. David Altman, Center for Creative Managing Editor, Colonel, USAF Leadership Dr. Douglas Lindsay, Dr. Marvin Berkowitz, University of Missouri- Editor in Chief, USAF (Ret) St. Louis Dr. John Abbatiello, Dr. Dana Born, Harvard University Book Review Editor, USAF (Ret) (Brig Gen, USAF, Retired) Dr. David Day, Claremont McKenna College Ms. Julie Imada, Editor & CCLD Strategic Dr. Shannon French, Case Western Communications Chief Dr. William Gardner, Texas Tech University JCLD is published at the United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Mr. Chad Hennings, Hennings Management Colorado. Articles in JCLD may be Corp reproduced in whole or in part without permission. A standard source credit line Mr. Max James, American Kiosk is required for each reprint or citation. Management For information about the Journal of Dr. Barbara Kellerman, Harvard University Character and Leadership Development or the U.S. Air Force Academy’s Center Dr. Robert Kelley, Carnegie Mellon for Character and Leadership University Development or to be added to the Association of Graduates Journal’s electronic subscription list, Ms. Cathy McClain, (Colonel, USAF, Retired) contact us at: Dr. Michael Mumford, University of [email protected] Oklahoma Phone: 719-333-4904 Dr. Gary Packard, United States Air Force Academy (Colonel, USAF) The Journal of Character & Leadership Development Dr. George Reed, University of Colorado at The Center for Character & Leadership Colorado Springs (Colonel, USA, Retired) Development Rice University U.S. -

The Need for a New Naval History of the First World War James Goldrick

Corbett Paper No 7 The need for a New Naval History of The First World War James Goldrick The Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies November 2011 The need for a New Naval History of the First World War James Goldrick Key Points . The history of naval operations in the First World War urgently requires re- examination. With the fast approaching centenary, it will be important that the story of the war at sea be recognised as profoundly significant for the course and outcome of the conflict. There is a risk that popular fascination for the bloody campaign on the Western Front will conceal the reality that the Great War was also a maritime and global conflict. We understand less of 1914-1918 at sea than we do of the war on land. Ironically, we also understand less about the period than we do for the naval wars of 1793-1815. Research over the last few decades has completely revised our understanding of many aspects of naval operations. That work needs to be synthesized and applied to the conduct of the naval war as a whole. There are important parallels with the present day for modern maritime strategy and operations in the challenges that navies faced in exercising sea power effectively within a globalised world. Gaining a much better understanding of the issues of 1914-1918 may help cast light on some of the complex problems that navies must now master. James Goldrick is a Rear Admiral in the Royal Australian Navy and currently serving as Commander of the Australian Defence College. -

Japanese Geopolitics and the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

64-12,804 JO. Yung-Hwan, 1932- JAPANESE GEOPOLITICS AND THE GREATER EAST ASIA CO-PROSPERITY SPHERE. The American University, Ph.D., 1964 Political Science, international law and relations University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Copyright by Yung-Hwan Jo 1965 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. JAPANESE GEOPOLITICS AND THE GREATER EAST ASIA CO-PROSPERITY SPHERE by Yung-Hwan Jo Submitted to the Faoulty of the Graduate School ef The Amerioan University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Dootor of Philosophy in International Relations and Organization Signatures of Committee: Chairman LiwLi^^ sdt-C'Ut'tUVC'Uo-iU i L’yL ■ ; June 1964 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY The Amerioan University LIBRARY Washington, D. C. JUL9 1964 WASHINGTON. D. C. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PREFACE This is a study of the Greater East Asia Co- Prosperity Sphere with emphasis on the influence of geo political thought in the formation of its concept. It is therefore a rather technical study of one aspect of Japanese diplomacy. Practically no studies have been made con cerning the influence of geopolitics on Japanese foreign policy. It is not the purpose of this study to attaok or defend the geopolitics or the concept of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere at any stage of its development, but rather to understand it. The principal data used in preparing this work are: (l) Various records of the International Military Tribunal of the Far East; (2) microfilmed arohives of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1868-1945; (3) materials written by Japanese geopoliticians as well as Haushofer; and (4) letters from authorities in the different aspects of this work. -

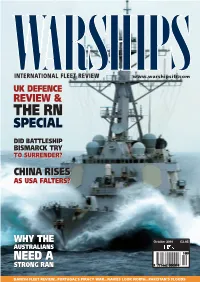

WIFR Did Battleship Bismarck Try to Surrender?

WIFR OCT 2010 FRONT COVER _WIFR OCT 2010 FRONT COVER 15/09/2010 13:28 Page 1 INTERNATIONAL FLEET REVIEW www.warshipsifr.com UK DEFENCE REVIEW & THE RN SPECIAL DID BATTLESHIP BISMARCK TRY TO SURRENDER? CHINA RISES AS USA FALTERS? WHY THE October 2010 £3.95 AUSTRALIANS NEED A SSTTRROONNGG RRAANN DANISH FLEET REVIEW...PORTUGAL’S PIRACY WAR...NAVIES LOOK NORTH...PAKISTAN’S FLOODS writing, alters perspective, and is Lef t , main image: ‘The End of therefore potentially controversial. the Bismarck’ by leading UK maritime artist Paul Wright RSMA. Having found the surrender angle I © Paul Wright. asked myself what else had gone For further information e-mail: untold? [email protected] In looking at already published Lef t , inset : HMS Rodney’s accounts of the Bismarck Action I Tommy Byers, w ho saw signs t hat realised that, while they covered Bismarck sailors w ere t rying t o DID BATTLESHIP surrender. the final battle - some quite vividly - none of them, in my opinion, quite Photo: Byers Collection. conveyed the full horror. When Tommy Byers wrote to Baron von Müllenheim-Rechberg, the senior mind by the time they had been BISMARCK TRY TO surviving German officer, in the chased and harassed by the Royal early 1990s to ask if any Bismarck Navy for several days. On the day of survivors had seen signs of battle it only took 40 minutes, or surrender attempts aboard their less, to reduce Bismarck to a own ship, the Baron could not floating hell. It was understandable help. Nobody among those who that while some of the German could have revealed the truth had battleship’s crew fought on - being survived.