State, Society and Governance in Melanesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Lepani I

Innovations for Successful Societies Innovations for Successful Societies AN INITIATIVE OF THE WOODROW WILSON SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS AND THE BOBST CENTER FOR PEACE AND JUSTICE Innovations for Successful Societies Innovations for Successful Societies Series: Governance Traps Interview no.: P2 Innovations for Successful Societies Innovations for Successful Societies Interviewee: Charles Lepani Interviewer: Matthew Devlin Date of Interview: 15 March 2009 Location: Canberra, Australia Innovations for Successful Societies Innovations for Successful Societies Innovations for Successful Societies, Bobst Center for Peace and Justice Princeton University, 83 Prospect Avenue, Princeton, New Jersey, 08544, USA www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties Use of this transcript is governed by ISS Terms of Use, available at www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties DEVLIN: Today is March 15th, 2010. We’re in Canberra, Australia, with His Excellency Charles Lepani, Papua New Guinea’s high commissioner to Australia. The high commissioner was one of Papua New Guinea’s top public servants during the years we’ll be discussing today and has a rather unique insight into both the political dynamics that shaped those events and the administrative aspects of the implementation of Papua New Guinea’s decentralization. Mr. High Commissioner, thank you for joining us. LEPANI: Thank you. DEVLIN: If you don’t mind, I’d like to begin by first asking you how you came to enter the public service, and what positions you held over the years of your governmental career. LEPANI: I started off as a trained trade unionist. After high school in Queensland, Australia, I spent two years at the University of Papua New Guinea in 1967-68. -

Opportunities Await Japanese Investors

第3種郵便物認可 (3) THE JAPAN TIMES FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2011 5 Papua New Guinea independence day Opportunities await Japanese investors Looking forward to even friendlier relations with PNG Katsuo Yamashita relations between our two countries ever since CHAIRMAN, JAPAN-PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION Papua New Guinea’s independence 36 years Dennis T. Bebego natural resources ranging from ago. All of us in Japan wish a quick recovery CHARGE D’AFFAIRES A.I. OF PAPUA fisheries and forestry in the re- On behalf of the Japan-Papua New Guinea of Sir Michael Somare’s health and it is our NEW GUINEA newables sector to minerals as Association, I would like to express my sincere earnest hope that, in the near future, he will play well as oil and gas deposits both congratulations to the government and people his role to maintain and strengthen our close On Sept. 16, 1975, Papua New on land and on the seabed. Vast of Papua New Guinea, who relationships. Guinea became an independent arable land with year-round celebrate their 36th Independence I take this opportunity to express my deep state, with the transition to na- tropical weather presents op- Day today, Sept. 16. appreciation to the government and people of tionhood be- portunities for agricultural de- I am happy to note that Papua New Guinea for extending the sympathy ing smooth. To velopment. Tropical rain forests bilateral relations between our and a large amount of donations to the victims date, Papua New teeming with flora and fauna, two countries are getting closer from the March 11 Great East Japan Earthquake Guinea remains steep mountains and gorges and closer in recent years. -

World Bank Document

PNG Rural Communications ESMF E2429 &217(176 Acronyms.......................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Introduction........................................................................................................ 5 1.1 General Context of the Report.................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. 6 1.2.1 General Summary ................................................................................................................. 6 Public Disclosure Authorized 1.2.2 Field Report Summary............................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 2. Environmental and Social Management Framework ................................................. 9 2.1 Background to ESMF ................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Objectives of the ESMF............................................................................................................. 9 2.3 Background to PNG Information and Communication Sector ...................................................... 10 2.4 PNG’s Current Rural Communication Project Description ........................................................... 14 2.5 Project Location..................................................................................................................... -

FIRST DAY 3 August 2012 DRAFT HANSARD Subject; Page

FIRST DAY 3 August 2012 DRAFT HANSARD Subject; Page No. PRAYERS 1 COMMISSION TO ADMINISTER DECLARATIONS - CHIEF JUSTICE 2 RETURNS OF WRITS 2 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND OF LOYALTY 7 ELECTION OF THE SPEAKER 7 DECLARATION OF OFFICE AND OF LOYALTY - COMMISSION 9 ELECTION OF THE PRIME MINISTER 10 PRESENTATION OF PRIME MINISTER-ELECT TO THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL 12 SPECIAL ADJOURNMENT 26 ADJOURNMENT 26 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES CORRECTIONS TO DAILY DRAFT HANSARD The Draft Hansard is uncorrected. It is also privileged. Members have one week from the date of this issue of Draft Hansard in which to mate'coirectioiis to their speeches. Until the expiration of this one week period, Draft Hansard must not be quoted as a final and accurate report of the debates of the National Parliament Cnrrectirmg maybe marked on a photocopy of the Daily Draft Hansard and lodged at the Office of the Principal Parliamentary Reporter, Al-23 (next to the Security Control Room). Corrections should be authorised by signature and contain-liieitame, office and telephone number of the person Iransmitting/making the corrections. Amendments -cannot-be accepted over the phone. Corrections should relate only to inaccuracies. New matter may not be introduced. Sanrfa M. Haro PrinciDal Parliamentarv Reoorter FIRST DAY Friday 3 August, 2012 The National Parliament met at 10.00 a.m., pursuant to the Notice of His Excellency the Governor-General, Sir Michael Ogio, which was published in the National Gazette. The Clerk read the Notice. PRAYERS Rev Qogi Zonggereng, Papua District President of the Evangelical Lutheran of Papua New Guinea representing the Council of Churches to say Prayers: 'This is the day that the Lord has made, a reading from Psalm 1. -

I2I Text Paste Up

PART 3: THE LIMITS OF INDEPENDENCE Chapter 12 Independence and its Discontents apua New Guineans handled the transition to independence with flair, despite their Plimited experience, the speed with which they had to act and the explosive agenda that they inherited. With great skill and some luck, they brought their country united to independence with new institutions, a new public service, a guaranteed income and a home-made constitution. A Failing State? The coalition that achieved these feats tottered in 1978 when Julius Chan took the PPP into opposition, and collapsed in March 1980 when the Leader of the Opposition, Iambakey Okuk, won a no-confidence motion, naming Chan as preferred Prime Minister. Chan had quit the coalition over the attempt to buttress the Leadership Code (Chapter 9) and disagreement on relations between private business and public office. Somare returned to office after the 1982 election but once again he was ousted in mid- term by a vote of no confidence, yielding to the ambitious young Western Highlander Paias Wingti. The pattern was now set, whereby coalitions are formed after an election but no government survives the fixed five-year parliamentary term. Votes of no confi- dence are the mechanism for replacing one opportunist coalition with another. By this device, Wingti was replaced by Rabbie Namaliu, who yielded to Wingti again, who was replaced by Chan, whose coalition collapsed in the wake of a bungled attempt to employ mercenaries (see below). After the 1997 election, Bill Skate — a gregarious accountant from Gulf Province, Governor of Port Moresby and cheerful opportunist — held a Cabinet together for nearly two years. -

Does MP Funding Work (Politically) in PNG?

Published on September 6, 2021 Part of a mural at PNG Parliament House (Marc Tarlock/Flickr) Does MP funding work (politically) in PNG? By Maholopa Laveil and Michael Kabuni In Papua New Guinea, District Services Improvement Program (DSIP) funding, given to 89 MPs representing open seats, is often talked of as a tool used to maintain government coalitions and increase an MP’s chances of being re-elected. In this post we investigate whether the funds really do help hold together governing coalitions and assist MPs in their quest for re-election. Link: https://devpolicy.org/does-mp-funding-work-politically-in-png-20210906/ Page 1 of 4 Date downloaded: October 2, 2021 Published on September 6, 2021 It has been argued that DSIP funds were introduced as a tool for holding together political coalitions. Their popularity among MPs is thought to stem from their utility as a means of rewarding and expanding an MP’s support base. As DSIP data is now available, it is possible to test if these beliefs are actually correct. Is there a relationship between DSIP funds and government tenure? And between DSIP funds and the overall election rate of open MPs? The following charts show these relationships. At first glance, the first chart appears to show a positive correlation between DSIP volumes (the sum of real DSIP funds disbursed in each year they were PM) and prime ministers’ tenures. Governments have lasted longer on average when real (inflation-adjusted) DSIP volumes have been higher. However, this relationship is driven entirely by two outliers: Sir Michael Somare’s tenure from Link: https://devpolicy.org/does-mp-funding-work-politically-in-png-20210906/ Page 2 of 4 Date downloaded: October 2, 2021 Published on September 6, 2021 2002 to 2011, and Peter O’Neill’s tenure from 2011 to 2019. -

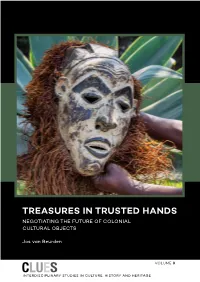

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

Papua New Guinea Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Papua New Guinea Country Report Status Index 1-10 5.56 # 69 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 5.95 # 62 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 5.18 # 75 of 129 Management Index 1-10 4.74 # 73 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Papua New Guinea Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Papua New Guinea 2 Key Indicators Population M 7.2 HDI 0.466 GDP p.c. $ 2898.1 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 2.2 HDI rank of 187 156 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 62.2 UN Education Index 0.318 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 12.6 Gender inequality2 0.617 Aid per capita $ 82.1 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary During the period under review, Papua New Guinea (PNG) made slight progress toward providing its citizens with greater freedom of choice by improving the state of democracy and its market- based economy. -

Papua New Guinea Vision 2050

i THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA PAPUA NEW GUINEA VISION 2050 National Strategic Plan Taskforce “WE LEADERS AND PEOPLE MUST KNOW WHERE WE WANT TO GO BEFORE WE CAN DECIDE HOW WE SHOULD GET THERE. BEFORE A DRIVER STARTS A MOTOR CAR, HE SHOULD FIRST DECIDE ON HIS DESTINATION. OTHERWISE HIS DRIVING WILL BE WITHOUT PURPOSE, AND HE WILL ACHIEVE NOTHING. WE PAPUA NEW GUINEANS ARE NOW IN THE DRIVING SEAT. THE ROAD WHICH WE SHOULD FOLLOW OUGHT TO BE MARKED OUT SO THAT ALL WILL KNOW THE WAY AHEAD.” (Constitutional Planning Committee (CPC) Report, 1974, Chapter 2, Section 4) ii ii CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................................... v THE NEXT GENERATION OF NATION BUILDERS ......................................................................................... x VISION 2050: OUR PEOPLE’S VISION ....................................................................................................... xii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... xiv DIRECTIONAL AND ENABLING STATEMENTS ............................................................................................. 1 Directional Statement ........................................................................................................................... 1 Pillars for the Vision ............................................................................................................................. -

POLITICAL LIFE WRITING in the Pacific Reflections on Practice

POLITICAL LIFE WRITING in the Pacific Reflections on Practice POLITICAL LIFE WRITING in the Pacific Reflections on Practice Edited by JACK CORBETT AND BRIJ V. LAL Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Political life writing in the Pacific : reflections on practice / Jack Corbett, Brij V. Lal, editors. ISBN: 9781925022605 (paperback) 9781925022612 (ebook) Subjects: Politicians--Islands of the Pacific--Biography. Authorship--Social aspects. Political science--Social aspects. Research--Moral and ethical aspects. Islands of the Pacific--Politics and government--Biography. Other Creators/Contributors: Corbett, Jack, editor. Lal, Brij V., editor. Dewey Number: 324.2092 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press Revised edition © August 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Tables . vii Preface . ix Contributors . xi 1. Practising Political Life Writing in the Pacific . 1 Jack Corbett 2 . Political Life Writing in Papua New Guinea . 13 Jonathan Ritchie 3 . Understanding Solomon . 33 Christopher Chevalier 4 . The ‘Pawa Meri’ Project . 47 Ceridwen Spark 5 . ‘End of a Phase of History’ . 59 Brij V. Lal 6 . Random Thoughts of an Occasional Practitioner . 75 Deryck Scarr 7 . Walking the Line between Anga Fakatonga and Anga Fakapalangi . 87 Areti Metuamate 8. Writing Influential Lives . -

MEKERE - Miuri Lareva

MEKERE - Miuri Lareva. Welcome to Mekere’s brothers - Elavo and Ivasa Morauta, and his sisters – Aru and Morisarea, and their children. The families of his deceased brothers, Moreare, Hasu and Siviri. From the Morauta Hasu (Mekere’s father’s) Family, Mekere’s aunts Moreare Hasu and Kauoti Hasu, their children and grandchildren. The children and grandchildren of Tete, Evera, Morisarea, Pukari, Sauka and Morara Hasu. And of Mekere’s mother Morikoai Elavo’s family, the children and grandchildren of Marere, Eae and Moriterope Elavo. Some sadness is so profound that it must be heard in the silence between the words. So it is with the death of our friend Mekere. When we were young, Mekere and I learned together about how humanity is governed. Over recent years we learned together about growing old. We shared the new things we learned as they happened in between. I will not use the time we have together today to dwell on the sadness of what we have lost and what we will miss forever. It is time to reflect on what we have learned from a full life lived well. The life of a good and great man. A good man who spent his whole adult life thinking about and working towards what could be made better for his country. A great man, who showed Papua New Guineans that governance as solid as humans have made anywhere could be sculpted in their beautiful and troubled land. A wise man, who knew that nothing was ever so good that it could not break down; or so bad that it could not be recovered. -

Accessing Literature on the Baha'i Faith: Emerging Search Technologies

Accessing Literature on the Baha'i Faith: Emerging Search Technologies GRAHAM HASSALL Abstract This article surveys some current search technologies that can be used to find documentation on the Baha'f religion. The capacity to search and retrieve docu ments has increased at a phenomenal pace in the past three decades. Search tech nologies have multiplied and become more both_ effective and more accessible. Emphasis has shifted from seeking information toward making the best use of the information found. Deeper access to information has expanded the range of research questions that we may dare to ask Resume eet article aborde des technologies de recherche courantes pouvant servir a trou ver de l'information sur la religion baha.'fe. Depuis trente ans, la capacite de chercher et d' extraire des documents a connu une croissance phenomenale. Les technologies de recherche se sont multipliees et sont maintenant plus efficaces et plus accessibles. L'accent est aujourd'hui mis sur l'exploitation efficiente de l'in formation recueillie plutot que sur la recherche de l'information comme telle. Un acces plus exhaustif a l'information a aussi permis d'elargir la gamme des ques tions de recherche qu'il est possible de poser. Resumen Este artfculo estudia algunas tecnologias actuales de busqueda que pueden ser utilizadas para encontrar documentaci6n acerca de la religi6n Baha'i. La capaci dad de buscar y recuperar documentos ha incrementado a un paso fenomenal en las ultimas tres decadas. Tecnologias de busqueda han muItiplicado y han llegado 35 36 The Journal qfBaha'i Studies 20. 1/4.2010 Accessing Literature on the Bah6.'i Faith 37 a ser mas efectivas y accesibles.