Management Plans for Mardon Skipper (Polites Mardon Ssp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butterflies of the Wesleyan Campus

BUTTERFLIES OF THE WESLEYAN CAMPUS SWALLOWTAILS Hairstreaks (Subfamily - Theclinae) (Family PAPILIONIDAE) Great Purple Hairstreak - Atlides halesus Coral Hairstreak - Satyrium titus True Swallowtails Banded Hairstreak - Satyrium calanus (Subfamily - Papilioninae) Striped Hairstreak - Satyrium liparops Pipevine Swallowtail - Battus philenor Henry’s Elfin - Callophrys henrici Zebra Swallowtail - Eurytides marcellus Eastern Pine Elfin - Callophrys niphon Black Swallowtail - Papilio polyxenes Juniper Hairstreak - Callophrys gryneus Giant Swallowtail - Papilio cresphontes White M Hairstreak - Parrhasius m-album Eastern Tiger Swallowtail - Papilio glaucus Gray Hairstreak - Strymon melinus Spicebush Swallowtail - Papilio troilus Red-banded Hairstreak - Calycopis cecrops Palamedes Swallowtail - Papilio palamedes Blues (Subfamily - Polommatinae) Ceraunus Blue - Hemiargus ceraunus Eastern-Tailed Blue - Everes comyntas WHITES AND SULPHURS Spring Azure - Celastrina ladon (Family PIERIDAE) Whites (Subfamily - Pierinae) BRUSHFOOTS Cabbage White - Pieris rapae (Family NYMPHALIDAE) Falcate Orangetip - Anthocharis midea Snouts (Subfamily - Libytheinae) American Snout - Libytheana carinenta Sulphurs and Yellows (Subfamily - Coliadinae) Clouded Sulphur - Colias philodice Heliconians and Fritillaries Orange Sulphur - Colias eurytheme (Subfamily - Heliconiinae) Southern Dogface - Colias cesonia Gulf Fritillary - Agraulis vanillae Cloudless Sulphur - Phoebis sennae Zebra Heliconian - Heliconius charithonia Barred Yellow - Eurema daira Variegated Fritillary -

Révision Taxinomique Et Nomenclaturale Des Rhopalocera Et Des Zygaenidae De France Métropolitaine

Direction de la Recherche, de l’Expertise et de la Valorisation Direction Déléguée au Développement Durable, à la Conservation de la Nature et à l’Expertise Service du Patrimoine Naturel Dupont P, Luquet G. Chr., Demerges D., Drouet E. Révision taxinomique et nomenclaturale des Rhopalocera et des Zygaenidae de France métropolitaine. Conséquences sur l’acquisition et la gestion des données d’inventaire. Rapport SPN 2013 - 19 (Septembre 2013) Dupont (Pascal), Demerges (David), Drouet (Eric) et Luquet (Gérard Chr.). 2013. Révision systématique, taxinomique et nomenclaturale des Rhopalocera et des Zygaenidae de France métropolitaine. Conséquences sur l’acquisition et la gestion des données d’inventaire. Rapport MMNHN-SPN 2013 - 19, 201 p. Résumé : Les études de phylogénie moléculaire sur les Lépidoptères Rhopalocères et Zygènes sont de plus en plus nombreuses ces dernières années modifiant la systématique et la taxinomie de ces deux groupes. Une mise à jour complète est réalisée dans ce travail. Un cadre décisionnel a été élaboré pour les niveaux spécifiques et infra-spécifique avec une approche intégrative de la taxinomie. Ce cadre intégre notamment un aspect biogéographique en tenant compte des zones-refuges potentielles pour les espèces au cours du dernier maximum glaciaire. Cette démarche permet d’avoir une approche homogène pour le classement des taxa aux niveaux spécifiques et infra-spécifiques. Les conséquences pour l’acquisition des données dans le cadre d’un inventaire national sont développées. Summary : Studies on molecular phylogenies of Butterflies and Burnets have been increasingly frequent in the recent years, changing the systematics and taxonomy of these two groups. A full update has been performed in this work. -

Superior National Forest

Admirals & Relatives Subfamily Limenitidinae Skippers Family Hesperiidae £ Viceroy Limenitis archippus Spread-wing Skippers Subfamily Pyrginae £ Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus clarus £ Dreamy Duskywing Erynnis icelus £ Juvenal’s Duskywing Erynnis juvenalis £ Northern Cloudywing Thorybes pylades Butterflies of the £ White Admiral Limenitis arthemis arthemis Superior Satyrs Subfamily Satyrinae National Forest £ Common Wood-nymph Cercyonis pegala £ Common Ringlet Coenonympha tullia £ Northern Pearly-eye Enodia anthedon Skipperlings Subfamily Heteropterinae £ Arctic Skipper Carterocephalus palaemon £ Mancinus Alpine Erebia disa mancinus R9SS £ Red-disked Alpine Erebia discoidalis R9SS £ Little Wood-satyr Megisto cymela Grass-Skippers Subfamily Hesperiinae £ Pepper & Salt Skipper Amblyscirtes hegon £ Macoun’s Arctic Oeneis macounii £ Common Roadside-Skipper Amblyscirtes vialis £ Jutta Arctic Oeneis jutta (R9SS) £ Least Skipper Ancyloxypha numitor Northern Crescent £ Eyed Brown Satyrodes eurydice £ Dun Skipper Euphyes vestris Phyciodes selenis £ Common Branded Skipper Hesperia comma £ Indian Skipper Hesperia sassacus Monarchs Subfamily Danainae £ Hobomok Skipper Poanes hobomok £ Monarch Danaus plexippus £ Long Dash Polites mystic £ Peck’s Skipper Polites peckius £ Tawny-edged Skipper Polites themistocles £ European Skipper Thymelicus lineola LINKS: http://www.naba.org/ The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination http://www.butterfliesandmoths.org/ in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national -

Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis Persius Persius

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada ENDANGERED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 41 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge M.L. Holder for writing the status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. COSEWIC also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Environment Canada. The COSEWIC report review was overseen and edited by Theresa B. Fowler, Co-chair, COSEWIC Arthropods Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’Hespérie Persius de l’Est (Erynnis persius persius) au Canada. Cover illustration: Eastern Persius Duskywing — Original drawing by Andrea Kingsley ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2006 Catalogue No. CW69-14/475-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43258-4 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name Eastern Persius Duskywing Scientific name Erynnis persius persius Status Endangered Reason for designation This lupine-feeding butterfly has been confirmed from only two sites in Canada. -

Mardon Skipper Site Management Plans

Mardon Skipper (Polites mardon) Site Management Plans Gifford Pinchot National Forest Service Cowlitz Valley Ranger District Prepared by John Jakubowski North Zone Wildlife Biologist Reviewed by Rich Hatfield, The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation October 2, 2015 Cowlitz Valley Ranger District Mardon Skipper Sites Group Meadow Longitude Latitude Area (acres) Elevation (ft.) Midway Midway 121 32.0 46 21.2 8 4,313 Midway PCT 121 31.1 46 21.1 2 4,530 Midway 115 Spur 121 30.9 46 21.0 3 4,494 Midway Grapefern 121 30.9 46 21.5 3 4,722 Midway 7A North 121 31.4 46 21.5 2 4,657 Midway 7A South 121 31.5 46 21.4 2 4,625 Midway 7A 121 31.1 46 21.4 7 4,676 Muddy Muddy 121 32.2 46.18.5 4 4,450 Muddy Lupine 121 31.8 46 18.7 3 4,398 Spring Cr Spring Cr. 121 33.5 46 20.4 unknown 3,900 Goal of the Management Plans Maintain and improve grassland/forb habitat at known occupancy meadow sites to ensure continued occupancy by mardon skipper butterfly as well as other important pollinator species such as western bumble bee. 1 Introduction On the Gifford Pinchot National Forest (GPNF), mardon skippers were first detected on the Mt. Adams Ranger District (MTA) in 2000 and on Cowlitz Valley Ranger District (CVRD) in 2002. Mardon skippers are known to inhabit ten, upland dry grassy meadows on the CVRD. Portions of the meadows are mesic and are unsuitable mardon skipper habitat. -

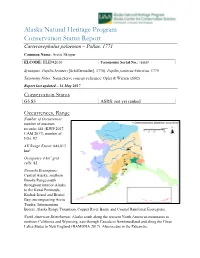

Alaska Natural Heritage Program Conservation Status Report Carterocephalus Palaemon – Pallas, 1771 Common Name: Arctic Skipper

Alaska Natural Heritage Program Conservation Status Report Carterocephalus palaemon – Pallas, 1771 Common Name: Arctic Skipper ELCODE: IILEP42010 Taxonomic Serial No.: 188607 Synonyms: Papilio brontes ([Schiffermüller], 1775), Papilio paniscus Fabricius, 1775 Taxonomy Notes: NatureServe concept reference: Opler & Warren (2002). Report last updated – 16 May 2017 Conservation Status G5 S5 ASRS: not yet ranked Occurrences, Range Number of Occurrences: number of museum records: 444 (KWP 2017, UAM 2017), number of EOs: 82 AK Range Extent: 644,013 km2 Occupancy 4 km2 grid cells: 82 Nowacki Ecoregions: Central Alaska: southern Brooks Range south throughout interior Alaska to the Kenai Peninsula, Kodiak Island and Bristol Bay; encompassing Arctic Tundra, Intermontane Boreal, Alaska Range Transition, Copper River Basin, and Coastal Rainforest Ecoregions. North American Distribution: Alaska south along the western North American mountains to northern California and Wyoming, east through Canada to Newfoundland and along the Great Lakes States to New England (BAMONA 2017). Also occurs in the Palearctic. Trends Short-term: Proportion collected has declined significantly (>10% change) since the 2000’s; however, the 2000’s had a relatively large collection that may represent a targeted study rather than an increase in population. We therefore consider the short-term trend to be “relatively stable” in the rank calculator to avoid over-emphasis on the subnational rarity rank. Long-term: The proportion collected has fluctuated since the 1950’s (3% to 21%), but with the exception of the 2000’s has stayed relatively stable (<10% change). Carterocephalus palaemon Collections in Alaska 160 40 140 35 120 30 100 25 80 20 60 15 40 10 20 5 Percent of Museum Collections Numberof Museum Collections 0 0 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Collections by Decade C. -

The Consequences of a Management Strategy for the Endangered Karner Blue Butterfly

THE CONSEQUENCES OF A MANAGEMENT STRATEGY FOR THE ENDANGERED KARNER BLUE BUTTERFLY Bradley A. Pickens A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2006 Committee: Karen V. Root, Advisor Helen J. Michaels Juan L. Bouzat © 2006 Bradley A. Pickens All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Karen V. Root, Advisor The effects of management on threatened and endangered species are difficult to discern, and yet, are vitally important for implementing adaptive management. The federally endangered Karner blue butterfly (Karner blue), Lycaeides melissa samuelis inhabits oak savanna or pine barrens, is a specialist on its host-plant, wild blue lupine, Lupinus perennis, and has two broods per year. The Karner blue was reintroduced into the globally rare black oak/lupine savannas of Ohio, USA in 1998. Current management practices involve burning 1/3, mowing 1/3, and leaving 1/3 of the lupine stems unmanaged at each site. Prescribed burning generally kills any Karner blue eggs present, so a trade-off exists between burning to maintain the habitat and Karner blue mortality. The objective of my research was to quantify the effects of this management strategy on the Karner blue. In the first part of my study, I examined several environmental factors, which influenced the nutritional quality (nitrogen and water content) of lupine to the Karner blue. My results showed management did not affect lupine nutrition for either brood. For the second brood, I found that vegetation density best predicted lupine nutritional quality, but canopy cover and aspect had an impact as well. -

Attempted Interspecific Mating by an Arctic Skipper with a European Skipper

INSECTS ATTEMPTED INTERSPECIFIC MATING BY AN ARCTIC SKIPPER WITH A EUROPEAN SKIPPER Peter Taylor P.O. Box 597, Pinawa, MB R0E 1L0, E-mail: <[email protected]> At about 15:15 h on 3 July 2011, focused, shows the Arctic skipper’s I observed a prolonged pursuit of a abdomen curved sideways in a J-shape, European skipper (Thymelicus lineola) almost touching the tip of the European by an Arctic skipper (Carterocephalus skipper’s abdomen in what appears palaemon). This took place along Alice to be a copulation attempt (Fig. 1d). Chambers Trail (50.17° N, 95.92° W) Frequent short flights by the European near the Pinawa Channel, a small branch skipper may have been an attempt to of the Winnipeg River in southeastern discourage its suitor – a known tactic used Manitoba. This secluded section of the by unreceptive female butterflies1 – but it Trans-Canada Trail passes through may simply have been disturbed by my moist, mature mixed-wood forest with close approach. Otherwise, the European small, sunlit openings that offer many skipper showed no obvious response to opportunities to observe and photograph the Arctic skipper’s advances. butterflies and dragonflies during the summer months. These two species are classified in separate subfamilies (Arctic skipper in The skipper pursuit continued for Heteropterinae, European skipper in about four minutes, and I obtained Hesperiinae). Both species are only 14 photographs, four of which are slightly dimorphic, and while the Arctic reproduced here (Fig. 1, see inside skipper’s behaviour indicates it was a front cover). The behaviour appeared male, it is not certain that the European to be attempted courtship, rather than a skipper was a female. -

Spineless Spineless Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E

Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates Edited by Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Spineless Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates of the world’s Status and trends Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates Edited by Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Disclaimer The designation of the geographic entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expressions of any opinion on the part of ZSL, IUCN or Wildscreen concerning the legal status of any country, territory, area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation Collen B, Böhm M, Kemp R & Baillie JEM (2012) Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates. Zoological Society of London, United Kingdom ISBN 978-0-900881-68-8 Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates (paperback) 978-0-900881-70-1 Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates (online version) Editors Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Zoological Society of London Founded in 1826, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is an international scientifi c, conservation and educational charity: our key role is the conservation of animals and their habitats. www.zsl.org International Union for Conservation of Nature International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) helps the world fi nd pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. www.iucn.org Wildscreen Wildscreen is a UK-based charity, whose mission is to use the power of wildlife imagery to inspire the global community to discover, value and protect the natural world. -

Butterflies Swan Island

Checkerspots & Crescents Inornate Ringlet ↓ Coenonympha tullia The Ringlet has a Harris’s Checkerspot Chlosyne harrisii bouncy, irregular Pearl Crescent ↓ Phyciodes tharos flight pattern. Abundant in open Crescents fly from fields from late May May to October. to early October. Especially common Common Wood Nymph ↓ Cercyonis pegala on dirt roads. Pearl and Northern hard The Common to differentiate. Wood Nymph is Northern Pearl Crescent Phyciodes cocyta very abundant. Flies from July to Eastern Comma Polygonia comma Sept. along wood Mourning Cloak Nymphalis antiopa edges and fields. Red Admiral Vanessa atalanta ______________________________________ Butterflies American Lady ↓ Vanessa virginiensis ______________________________________ of ______________________________________ American Lady found on dirt Swan Island roads and open Perkins TWP, Maine patches in fields. Steve Powell Wildlife Flight period is April to October. Management Area White Admiral Limenitis arthemis Viceroy Limenitis archippus ______________________________________ ______________________________________ Satyrs Great Spangled Fritillary Northern Pearly-Eye Enodia anthedon Eyed Brown ↓ Satyrodes eurydice Eyed Brown found in wet, wooded Swan Island – Explore with us! www.maine.gov/swanisland edges. Has erratic Maine Butterfly Survey flight pattern. Flies Checklist and brochure created by Robert E. mbs.umf.maine.edu from late June to Gobeil and Rose Marie F. Gobeil in cooperation with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries Photos of Maine Butterflies early August. www.mainebutterflies.com and Wildlife (MDIFW). Photos by Rose Marie F. Gobeil Little Wood Satyr Megisto cymela ______________________________________ SECOND PRINTING: APRIL 2019 Skippers Pepper & Salt Skipper Amblyscirtes hegon Banded Hairstreak ↓ Satyrium calanus Swallowtails Banded Hairstreak: Silver-spotted Skipper ↓Epargyreus clarus uncommon, found Silver-spotted Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes in open glades in Skipper is large Canadian Tiger Swallowtail ↓ Papilio canadensis wooded areas. -

Oviposition Selection in Montane Habitats, Biological Conservation

Biological Conservation 143 (2010) 862–872 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Oviposition selection by a rare grass skipper Polites mardon in montane habitats: Advancing ecological understanding to develop conservation strategies Loni J. Beyer, Cheryl B. Schultz * Washington State University Vancouver, 14204 NE Salmon Creek Ave, Vancouver, WA 98686, USA article info abstract Article history: The Grass skipper subfamily (Hesperiinae) includes many at risk species across the globe. Conservation Received 31 March 2009 efforts for these skippers are hindered by insufficient information about their basic biology. Mardon skip- Received in revised form 3 November 2009 per (Polites mardon) is declining throughout its range. We surveyed mardon oviposition across nine study Accepted 25 December 2009 meadows in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest of Washington State. We conducted habitat surveys with Available online 21 January 2010 respect to oviposition (n = 269) and random (n = 270) locations, recording data on over 50 variables. Mar- don oviposited on 23 different graminoid species, yet are selective for specific graminoids within mead- Keywords: ows. Most frequent ovipositions across meadows occurred on Festuca idahoensis and Poa pratensis Butterfly (accounting for 112 of 269 total oviposition observations). Discriminant Function Analyses revealed that Graminoids Habitat preference mardon habitat was too variable to detect oviposition selection across study meadows, yet there was 2 Host selection strong selection occurring within meadows (r ranging from 0.82 to 0.99). Variables important to within Life history meadow selection were graminoid cover, height, and community; oviposition plant structure (leaf den- Management sity, height, area); insolation factors (tree abundance and canopy shading); and litter layer factors (cover Meadow and depth). -

Winneshiek County Butterflies

A must-buy book for the butterfly enthusiast is _____Northern Broken-dash U Jn-Jl _____Coral Hairstreak C Jn-Jl The Butterflies of Iowa by Dennis W. Schlicht, John Wallengrenia egeremet Satyrium titus C. Downy and Jeffrey C. Nekola; published by the _____Little Glassywing U Jn-Jl _____Acadian Hairstreak R Jn-Jl University of Iowa Press in 2007. Pompeius verna Satyrium acadica According toThe Butterflies of Iowa, the _____Delaware Skipper C Jn-Ag _____Hickory Hairstreak R Jl following butterflies have been collected at least Anatrytone logan Satyrium caryaevorum once in Winneshiek County since records were kept. _____Hobomok Skipper C M-Jn _____Edward’s Hairstreak R Jn-Jl Poanes hobomok Satyrium edwardsii Common Name Status Flight _____Black Dash U Jn-Ag _____Banded Hairstreak U Jn-Jl Scientific Name Euphyes conspicua Satyrium calanus _____Silver Spotted Skipper C M-S _____Pipevine Swallowtail R Ag _____Gray Hairstreak U M-O Epargyreus clarus Battus philenor Strymon melinus _____Southern Cloudywing U M-Ag _____Black Swallowtail C Ap-S _____Eastern Tailed-blue A Ap-O Thorybes bathyllus Papilio polyxenes Everes comyntas _____Northern Cloudywing C Jn-Jl _____Eastern Tiger Swallowtail C Ap-S _____Summer Azure A M-S Thorybes pylades Papilio glaucus Celastrina neglecta _____Sleepy Duskywing R M _____Spicebush Swallowtail R Jn-Jl _____Reakirt’s Blue R Jn-Ag Erynnis brizo Papilio troilus Echinargus isola _____Juvenal’s Duskywing U Ap-Jn _____Giant Swallowtail U M-S _____American Snout R Jn-O Erynnis juvenalis Papilio cresphontes Libytheana carinenta