A Study of the Life Cycle of the Chequered Skipper Butterfly Carterocephalus Palaemon (Pallas) [Online]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Révision Taxinomique Et Nomenclaturale Des Rhopalocera Et Des Zygaenidae De France Métropolitaine

Direction de la Recherche, de l’Expertise et de la Valorisation Direction Déléguée au Développement Durable, à la Conservation de la Nature et à l’Expertise Service du Patrimoine Naturel Dupont P, Luquet G. Chr., Demerges D., Drouet E. Révision taxinomique et nomenclaturale des Rhopalocera et des Zygaenidae de France métropolitaine. Conséquences sur l’acquisition et la gestion des données d’inventaire. Rapport SPN 2013 - 19 (Septembre 2013) Dupont (Pascal), Demerges (David), Drouet (Eric) et Luquet (Gérard Chr.). 2013. Révision systématique, taxinomique et nomenclaturale des Rhopalocera et des Zygaenidae de France métropolitaine. Conséquences sur l’acquisition et la gestion des données d’inventaire. Rapport MMNHN-SPN 2013 - 19, 201 p. Résumé : Les études de phylogénie moléculaire sur les Lépidoptères Rhopalocères et Zygènes sont de plus en plus nombreuses ces dernières années modifiant la systématique et la taxinomie de ces deux groupes. Une mise à jour complète est réalisée dans ce travail. Un cadre décisionnel a été élaboré pour les niveaux spécifiques et infra-spécifique avec une approche intégrative de la taxinomie. Ce cadre intégre notamment un aspect biogéographique en tenant compte des zones-refuges potentielles pour les espèces au cours du dernier maximum glaciaire. Cette démarche permet d’avoir une approche homogène pour le classement des taxa aux niveaux spécifiques et infra-spécifiques. Les conséquences pour l’acquisition des données dans le cadre d’un inventaire national sont développées. Summary : Studies on molecular phylogenies of Butterflies and Burnets have been increasingly frequent in the recent years, changing the systematics and taxonomy of these two groups. A full update has been performed in this work. -

Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis Persius Persius

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada ENDANGERED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 41 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge M.L. Holder for writing the status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. COSEWIC also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Environment Canada. The COSEWIC report review was overseen and edited by Theresa B. Fowler, Co-chair, COSEWIC Arthropods Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’Hespérie Persius de l’Est (Erynnis persius persius) au Canada. Cover illustration: Eastern Persius Duskywing — Original drawing by Andrea Kingsley ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2006 Catalogue No. CW69-14/475-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43258-4 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name Eastern Persius Duskywing Scientific name Erynnis persius persius Status Endangered Reason for designation This lupine-feeding butterfly has been confirmed from only two sites in Canada. -

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(S): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(s): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P. Barker, Lynn G. Clark, Jerrold I. Davis, Melvin R. Duvall, Gerald F. Guala, Catherine Hsiao, Elizabeth A. Kellogg, H. Peter Linder Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, Vol. 88, No. 3 (Summer, 2001), pp. 373-457 Published by: Missouri Botanical Garden Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3298585 Accessed: 06/10/2008 11:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mobot. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

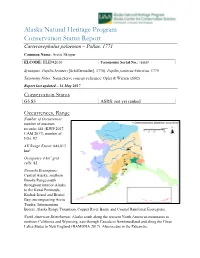

Alaska Natural Heritage Program Conservation Status Report Carterocephalus Palaemon – Pallas, 1771 Common Name: Arctic Skipper

Alaska Natural Heritage Program Conservation Status Report Carterocephalus palaemon – Pallas, 1771 Common Name: Arctic Skipper ELCODE: IILEP42010 Taxonomic Serial No.: 188607 Synonyms: Papilio brontes ([Schiffermüller], 1775), Papilio paniscus Fabricius, 1775 Taxonomy Notes: NatureServe concept reference: Opler & Warren (2002). Report last updated – 16 May 2017 Conservation Status G5 S5 ASRS: not yet ranked Occurrences, Range Number of Occurrences: number of museum records: 444 (KWP 2017, UAM 2017), number of EOs: 82 AK Range Extent: 644,013 km2 Occupancy 4 km2 grid cells: 82 Nowacki Ecoregions: Central Alaska: southern Brooks Range south throughout interior Alaska to the Kenai Peninsula, Kodiak Island and Bristol Bay; encompassing Arctic Tundra, Intermontane Boreal, Alaska Range Transition, Copper River Basin, and Coastal Rainforest Ecoregions. North American Distribution: Alaska south along the western North American mountains to northern California and Wyoming, east through Canada to Newfoundland and along the Great Lakes States to New England (BAMONA 2017). Also occurs in the Palearctic. Trends Short-term: Proportion collected has declined significantly (>10% change) since the 2000’s; however, the 2000’s had a relatively large collection that may represent a targeted study rather than an increase in population. We therefore consider the short-term trend to be “relatively stable” in the rank calculator to avoid over-emphasis on the subnational rarity rank. Long-term: The proportion collected has fluctuated since the 1950’s (3% to 21%), but with the exception of the 2000’s has stayed relatively stable (<10% change). Carterocephalus palaemon Collections in Alaska 160 40 140 35 120 30 100 25 80 20 60 15 40 10 20 5 Percent of Museum Collections Numberof Museum Collections 0 0 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Collections by Decade C. -

The Consequences of a Management Strategy for the Endangered Karner Blue Butterfly

THE CONSEQUENCES OF A MANAGEMENT STRATEGY FOR THE ENDANGERED KARNER BLUE BUTTERFLY Bradley A. Pickens A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2006 Committee: Karen V. Root, Advisor Helen J. Michaels Juan L. Bouzat © 2006 Bradley A. Pickens All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Karen V. Root, Advisor The effects of management on threatened and endangered species are difficult to discern, and yet, are vitally important for implementing adaptive management. The federally endangered Karner blue butterfly (Karner blue), Lycaeides melissa samuelis inhabits oak savanna or pine barrens, is a specialist on its host-plant, wild blue lupine, Lupinus perennis, and has two broods per year. The Karner blue was reintroduced into the globally rare black oak/lupine savannas of Ohio, USA in 1998. Current management practices involve burning 1/3, mowing 1/3, and leaving 1/3 of the lupine stems unmanaged at each site. Prescribed burning generally kills any Karner blue eggs present, so a trade-off exists between burning to maintain the habitat and Karner blue mortality. The objective of my research was to quantify the effects of this management strategy on the Karner blue. In the first part of my study, I examined several environmental factors, which influenced the nutritional quality (nitrogen and water content) of lupine to the Karner blue. My results showed management did not affect lupine nutrition for either brood. For the second brood, I found that vegetation density best predicted lupine nutritional quality, but canopy cover and aspect had an impact as well. -

Determinants of Successful Arthropod Eradication Programs

Biol Invasions (2014) 16:401–414 DOI 10.1007/s10530-013-0529-5 ORIGINAL PAPER Determinants of successful arthropod eradication programs Patrick C. Tobin • John M. Kean • David Maxwell Suckling • Deborah G. McCullough • Daniel A. Herms • Lloyd D. Stringer Received: 17 December 2012 / Accepted: 25 July 2013 / Published online: 27 August 2013 Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht (outside the USA) 2013 Abstract Despite substantial increases in public target species, method of detection, and the primary awareness and biosecurity systems, introductions of feeding guild of the target species. The outcome of non-native arthropods remain an unwelcomed conse- eradication efforts was not determined by program quence of escalating rates of international trade and costs, which were largely driven by the size of the travel. Detection of an established but unwanted non- infestation. The availability of taxon-specific control native organism can elicit a range of responses, tools appeared to increase the probability of eradica- including implementation of an eradication program. tion success. We believe GERDA, as an online Previous studies have reviewed the concept of erad- database, provides an objective repository of infor- ication, but these efforts were largely descriptive and mation that will play an invaluable role when future focused on selected case studies. We developed a eradication efforts are considered. Global Eradication and Response DAtabase (‘‘GER- DA’’) to facilitate an analysis of arthropod eradication Keywords Detection Á Eradication Á Invasive programs and determine the factors that influence species management Á Non-native pests eradication success and failure. We compiled data from 672 arthropod eradication programs targeting 130 non-native arthropod species implemented in 91 Introduction countries between 1890 and 2010. -

Attempted Interspecific Mating by an Arctic Skipper with a European Skipper

INSECTS ATTEMPTED INTERSPECIFIC MATING BY AN ARCTIC SKIPPER WITH A EUROPEAN SKIPPER Peter Taylor P.O. Box 597, Pinawa, MB R0E 1L0, E-mail: <[email protected]> At about 15:15 h on 3 July 2011, focused, shows the Arctic skipper’s I observed a prolonged pursuit of a abdomen curved sideways in a J-shape, European skipper (Thymelicus lineola) almost touching the tip of the European by an Arctic skipper (Carterocephalus skipper’s abdomen in what appears palaemon). This took place along Alice to be a copulation attempt (Fig. 1d). Chambers Trail (50.17° N, 95.92° W) Frequent short flights by the European near the Pinawa Channel, a small branch skipper may have been an attempt to of the Winnipeg River in southeastern discourage its suitor – a known tactic used Manitoba. This secluded section of the by unreceptive female butterflies1 – but it Trans-Canada Trail passes through may simply have been disturbed by my moist, mature mixed-wood forest with close approach. Otherwise, the European small, sunlit openings that offer many skipper showed no obvious response to opportunities to observe and photograph the Arctic skipper’s advances. butterflies and dragonflies during the summer months. These two species are classified in separate subfamilies (Arctic skipper in The skipper pursuit continued for Heteropterinae, European skipper in about four minutes, and I obtained Hesperiinae). Both species are only 14 photographs, four of which are slightly dimorphic, and while the Arctic reproduced here (Fig. 1, see inside skipper’s behaviour indicates it was a front cover). The behaviour appeared male, it is not certain that the European to be attempted courtship, rather than a skipper was a female. -

Slender False Brome (Brachypodium Sylvaticum Ssp. Sylvaticum): a New Invasive Plant in New York

QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER New York Flora Association - New York State Museum Institute Editors: Priscilla Titus and Steve Young; Assistant Editor: Connie Tedesco Correspondence to NYFA, 3140 CEC, Albany, NY 12230 Vol. 21 No. 1 Winter 2010 e-mail: [email protected] Dues $20/Year Website: www.nyflora.org SLENDER FALSE BROME (BRACHYPODIUM SYLVATICUM SSP. SYLVATICUM): A NEW INVASIVE PLANT IN NEW YORK by Steven Daniel and David Werier In early September we independently found and vouchered two populations of slender false brome (Brachypodium sylvaticum ssp. sylvaticum) in New York (Bergen Swamp in Genesee County and Connecticut Hill in Tompkins County [SW of the corner of Tower and Cayutaville Roads]). The population at Bergen Swamp has likely been established for at least a decade. The second author saw the Clumped Brachypodium sylvaticum plants exhibiting droop- slender false brome at ing leaves and inflorescences. Photo by Steven Daniel. Bergen in 2004 but never collected a specimen. Jay Greenberg (Bergen Swamp Preservation Society Trustee, personal communication) also noticed the plants along one of the main trails at Bergen beginning in or before the mid- 1990’s but didn’t know what it was. 1 This species is native to Asia, Europe, and North Africa (Shouliang and Phillips 2006) and has become naturalized in the Pacific Northwest and northern California (Johnson 2004, Piep 2007). In North America, slender false brome was first documented in Oregon in 1939 (Kaye 2001). In eastern North America it has previously only been found in Virginia (Piep 2007). Specimens from the New York populations have been verified by Tom Kaye (Institute for Applied Ecology), Rob Naczi (New York Botanical Garden), and Michael Piep (Intermountain Herbarium, Utah State University). -

Brachypodium Sylvaticum) Invasion in the Santa Cruz Mountains, California

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Summer 2013 Predicting Slender False Brome (Brachypodium sylvaticum) Invasion in the Santa Cruz Mountains, California Janine Ellen Bird San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Bird, Janine Ellen, "Predicting Slender False Brome (Brachypodium sylvaticum) Invasion in the Santa Cruz Mountains, California" (2013). Master's Theses. 4330. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.uxgg-7u9x https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PREDICTING SLENDER FALSE BROME ( BRACHYPODIUM SYLVATICUM) INVASION IN THE SANTA CRUZ MOUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Geography San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Janine E. Bird August 2013 © 2013 Janine E. Bird ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PREDICTING SLENDER FALSE BROME ( BRACHYPODIUM SYLVATICUM) INVASION IN THE SANTA CRUZ MOUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA by Janine E. Bird APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY August 2013 Dr. Richard Taketa Department of Geography Dr. M. Kathryn Davis Department of Geography Cynthia Powell Calflora ABSTRACT PREDICTING SLENDER FALSE BROME ( BRACHYPODIUM SYLVATICUM) INVASION IN THE SANTA CRUZ MOUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA by Janine E. Bird Early detection of an invasive species facilitates control and eradication. Slender false brome (Brachypodium sylvaticum) was first discovered in the Santa Cruz Mountains of Central California in 2003 as a non-native grass in redwood forests, competing with native vegetation. -

Investigating the Use of Herbicides to Control Invasive Grasses In

INVESTIGATING THE USE OF HERBICIDES TO CONTROL INVASIVE GRASSES IN PRAIRIE HABITATS: EFFECTS ON NON-TARGET BUTTERFLIES By CAITLIN C. LABAR A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Program in Environmental Science and Regional Planning MAY 2009 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of CAITLIN C. LABAR find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. __________________________________ Cheryl B. Schultz, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ John Bishop, Ph.D. __________________________________ Mary J. Linders, M.S. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I thank my graduate advisor, Cheryl B. Schultz for the opportunity to conduct this research, and for her guidance with this project and the manuscript. I would also like to thank my graduate committee Dr. John Bishop and Mary Linders for their comments and manuscript review. Many individuals assisted with fieldwork and data collection, and contributed in laboratory support. They include Crystal Hazen, Steven Gresswell, Samuel Lohmann, Kristine Casteel, Brenda Green, and Gretchen Johnson. Cliff Chapman (The Nature Conservancy) and Casey Dennehy (The Nature Conservancy) applied the sethoxydim herbicide for my study, and Ann Potter (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife), Dave Hays (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife) and Rod Gilbert (Fort Lewis) helped coordinate the project and provided suggestions. My fellow lab mates, Cheryl Russell, Leslie Rossmell, Loni Beyer, Alexa Carleton, and Erica Henry provided encouragement, feedback, and support, as well as occasional field assistance during this project. I am also very thankful to my friends and family for their love and support during the completion of my research and thesis. -

Pollen Morphology of Poaceae (Poales) in the Azores, Portugal

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/283696832 Pollen morphology of Poaceae (Poales) in the Azores, Portugal ARTICLE in GRANA · OCTOBER 2015 Impact Factor: 1.06 · DOI: 10.1080/00173134.2015.1096301 READS 33 4 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Vania Gonçalves-Esteves Maria A. Ventura Federal University of Rio de Janeiro University of the Azores 86 PUBLICATIONS 141 CITATIONS 43 PUBLICATIONS 44 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Maria A. Ventura letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 10 December 2015 Grana ISSN: 0017-3134 (Print) 1651-2049 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/sgra20 Pollen morphology of Poaceae (Poales) in the Azores, Portugal Leila Nunes Morgado, Vania Gonçalves-Esteves, Roberto Resendes & Maria Anunciação Mateus Ventura To cite this article: Leila Nunes Morgado, Vania Gonçalves-Esteves, Roberto Resendes & Maria Anunciação Mateus Ventura (2015) Pollen morphology of Poaceae (Poales) in the Azores, Portugal, Grana, 54:4, 282-293, DOI: 10.1080/00173134.2015.1096301 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00173134.2015.1096301 Published online: 04 Nov 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 13 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=sgra20 Download by: [b-on: Biblioteca do conhecimento -

EIG 8 Autumn 2010 (PDF, 4.0Mb)

NEWSLETTER Issue 8 October 2010 CONTENTS Page Chairman’s Introduction 2&3 Dates for your Diary / EIG Calendar/ Contact Details 4 European Butterflies – the taxonomy update 5&6 Agricultural Change and its implications for Butterflies In Eastern French Pyrenees 7,8,9&10 Monitoring the Sudeten Ringlet in Switzerland 11,12&13 Fundraising Tour to Slovenia (1) 14&15 Fundraising Trip to Slovenia & Orseg (2) 16 EIG Trip to Mt. Phalakron, Greece 17&18 At last, the Macedonian Grayling (Pseudochazara cingowskii) 19&20 Skiathos – Greece 21&22 Finding Apollo in the Julian Alps 23 In search of the Scarce Fritillary 24 Orseg National Park 25&26 The Butterfly Year – The late Butterfly season in Provence(Var) 26 Part 2 of Newsletter We are pleased to include an extract of Bernard Watts ‘European Butterflies a portrait in photographs’ on the Alcon Blue ( Phengaris = Maculinea alcon) This document will be sent as a pdf titled: Part II – Autumn 2010_alcon-brw.pdf 1 INTRODUCTION Editorial As I mentioned in the last newsletter Butterfly Conservation Europe (BCE) has now completed the Red List of European Butterflies using the new standardized IUCN 1 criteria. These are available on the IUCN website See http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist or the link on EIG website: http://www.bc-eig.org.uk/Newsletters.html where you can download the Red List Report for free as a .pdf. This massive piece of work was led by Chris van Swaay and is a major achievement for BCE. It covers all butterflies in Europe either in the EU27 countries but also continental Europe which includes Turkey west of the Bosphorus and Russia up to the Urals.