Consumer Perception of Food–Beverage Pairings the Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beer Experiences in and Around Salzburg Salzburg Beer Culture

#salzburgerbierkultur#salzburgbeer www.salzburg.info/beer-culture Beer experiences in and around Salzburg Salzburg Beer Culture Salzburg’s beer culture has a tradition dating back centuries which is continued today in the form of privately-run breweries and an exceptional culture of gastronomy. Each brewery is unique and has its own specialist style. Together, they represent Salzburg’s beer culture – the density of breweries in Salzburg is truly exceptional. Ingenious master brewers understand the advantages offered by independent brewing and make progressive and creative use of these benefits. Enjoy a wide range of beers in rustic inns and trendy bars. The landlords and their well-trained employees are both charming and full of expertise and can provide you with in-depth advice. The Salzburg beer culture experts share their knowledge with participants during walks, tours and courses. 2 3 Salzburg’s breweries Strong partners Hofbräu Kaltenhausen Of the 11 breweries in Salzburg, there are 5 inn-based breweries and Experts in creative and speciality beers 6 large-scale partners. The latter have come together and formed the Re-discovering tradition each day ‘ARGE Bierkultur’ association. Each of these breweries has its own Salzburg’s oldest brewery has been representing the craft of brewing since style and has specialised in a core field of expertise. The range of 1475. Each sip of Kaltenhausen beer combines creative new ideas with products on offer extends from traditional Salzburg-style beers to age-old brewing secrets to create an exceptional beer flavour. innovative creations. The brewery partners are also enhanced www.kaltenhausen.at by Kiesbye’s Bierkulturhaus, a training and meeting place for sharing knowledge of beer at the highest level. -

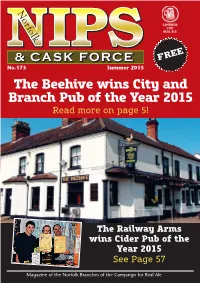

The Beehive Wins City and Branch Pub of the Year 2015 Read More on Page 5!

E FRE No.173 Summer 2015 The Beehive wins City and Branch Pub of the Year 2 01 5 Read more on page 5! The Railway Arms wins Cider Pub of the Year 2015 See Page 57 Magazine of the Norfolk Branches of the Campaign for Real Ale Norfolk Nips | Campaigning In this issue: Get behind the beer industry 3 Norwich & Norfolk POTY 5 Stig’s Words 6 Let’s get behind The Ed’lines 7 Pub and Brewery News 8-12 the beer industry Bar Man - How Much?? 15 CAMRA members vote for Beer Sommelier 16 a more inclusive campaign Cider POTY 17 Black Horse Rampant 19 Members of CAMRA, Europe’s is about the promotion and largest beer consumer group, championing of real ale, and The Albion - End of an Era 20 have reinforced the organisa - providing a choice for drinkers, tion’s positive approach to rather than outright opposition In Memory of Wolfe 22-23 campaigning for beer and pubs to other types of beer. Correspondence 23 by passing a series of progres - sive motions at its annual CAMRA chief executive Tim Green Dragon wins the Rural! 25 conference. Page said: “It was clear from the debate in the hall that the From the Archives 27 More than 1,200 CAMRA majority of members think that Key Keg debate 29 members attended the confer - criticising drinkers for not ence in Nottingham between choosing real ale is counter- The Rant 32 18-19 April and debated and productive. voted on 20 motions about Going to Gorleston 34-37 issues affecting the beer and CAMRA’s inclusive and Bar Man - Philosophy of 39 pub industry, as well as supportive attitude to the beer CAMRA’s future campaigning. -

Beer at the Heart of Country Pub Mark Dorber Is Passionate About Good Food, Good Wine and - Above All Else – Good Beer

Food & drink In association with East of England Co-op Beer at the heart of country pub Mark Dorber is passionate about good food, good wine and - above all else – good beer. Claire Holmes visited his newest project, The Swan at Stratford St Mary, to find out more atching food with has an appetite for excellence and beer isn’t exactly loves being able to showcase the something new, but very best of what the world has to beer – and the way it offer in relation to food and drink. can elevate the taste His two businesses embody this of different dishes – passion in a very real way – and you Mhas certainly started to grip the only have to look behind the bar or nation in recent years. at the menu to see this. Whether it’s because the drink To those who are interested in food itself has improved, because there’s and drink, Mark’s name may ring a a record number of breweries bell – and so it should. He is well opening or simply because we as a known as the man who helped nation have become more open to transform one of the UK’s best pubs the idea of drinking beer, it into a haven for diverse, interesting definitely seems to be the thing of and excellent food and drink. the moment. Indeed, during the 25 or so years And, it’s something that Mark that Mark was involved in The I The team at the Swan in Stratford St Mary - Ed Razzall, Jane and Mark Photos: SU ANDERSON Dorber has been extolling the White Horse at Parsons Green - Dorber and Steven Miles. -

AWARD-WINNING No

AWARD-WINNING No. 104 Winter 2014/15 www.camrabristol.org.uk NTS WE Multi-award-winningI magazine of the Bristol & District Branch of CAMRA, theS Campaign for Real Ale P (incorporating the Bath & Borders Branch) T PINTS WEST A small taste of the contents of this edition of Pints West to whet your appetite... PINTS WEST The multi-award-winning magazine of the Bristol & Page 22 District Branch of CAMRA, the Campaign for Real Page 7 Page 4 Ale, plus the Bath & Borders Branch Brought to you entirely by unpaid volunteers Page 34 Ten thousand copies of Pints West are distributed free to hundreds of pubs in and around the cities of Bristol and Bath ... and beyond. Also available to read on-line at: www.bristolcamra.org.uk REAL CIDER Published by the Bristol & District Branch of CAMRA, the Campaign for Real Ale, November 2014 © Next edition: end of February 2015 (probably). Page 12 Spread the word: any article in this publication may be reproduced provided the source (Pints West), including the contributor’s name where applicable, is stated. (No using logos or artwork without prior Page 18 permission.) Subscriptions: to be put on a mailing list (for UK addresses) send ten SOLD HERE standard 1st class stamps to the editor. CAMRA Good Beer Guide: suggestions for future entries, and Page 17 comments on existing ones, can be made to our GBG co-ordinator, Page 10 Martin Gray: [email protected]. If you have any pub updates: please enter them through whatpub.com or email details to [email protected]. -

Master of Beer Styles

USA Beer Styles Past and Present Beer Sommelier 1 Contents: Origins of U.S Brewing Traditional U.S. Beer Styles – German Lager – American Style Lager – Classic American Pilsner Style – Cream Ale – California Common Beer Recent Trends in U.S. Beer (Craft) Styles – American Pale Ale – American I.P.A. – American Amber Ale – Imperial/Double I.P.A. Current “Craft” Trends American Brewing and Beer Styles In the Beginning…A Little History Brewing new to N. America <500 years Based upon European brewing traditions Prior to mid-1800s English Ales were favored – Dominant brewing culture of the time – Refrigeration difficult – Majority of inhabitants were of English extraction Vegetables sometimes used: beets, peas American Styles The Lager Revolution 1842 Pilsner created, rapidly popularized in Europe German immigration to the U.S. highest in mid-1800s. – They brought brewing traditions with them – Many settled in Midwest As a result, lager brewing rapidly adopted in the U.S. American Styles The Lager Revolution…continued German Immigration continued Until 1920, "American Brewer" published in German New beers created: – American Lager – Steam Beer American Styles The Lager Revolution…continued American Lager About 30% corn or rice Rest 6-row American malt Adjunct initially used to: – Improve clarity (protein dilution) – Reduce cost – Ration goods/materials during WW I ~77% of US beer consumption American Styles The Lager Revolution…continued American-Style Lager Flavors should be subtle and complex, no one ingredient dominating Malt sweetness = light to mild Hop bitterness, flavor and aroma negligible to very light Light, fruity esters acceptable Carbon dioxide is a primary flavor attribute/characteristic American Lager ABV 3.8-5.3% SRM 2-4 IBU 5-15 O.G. -

Want to Reach Over 7,000, 000 European Travellers Every Month ?

TRAVELLER A MAGAZINE FOR THE GET-UP-AND-GO GENERATION Want to reach over 7,000,000 European travellers every month ? Advertise in one of Europe's most read magazines WINNER WINNER WINNER WINNER WINNER CUSTOMER DESIGN TEAM OF THE FEATURES JOURNALIST EDITOR CUSTOMER MAGAZINE OF THE YEAR 2017 OF THE YEAR 2017 OF THE YEAR MAGAZINE OF THE YEAR 2017 BUSINESS TRAVEL BUSINESS TRAVEL BRANDED CONTENT YEAR 2015 TRAVEL MEDIA JOURNALISM JOURNALISM 2015 TRAVEL MEDIA AWARDS AWARDS AWARDS BSME AWARDS AWARDS Why travel media? Did you know? As more people take more journeys so travel media is growing stronger and more Airline passenger numbers are growing by influential. easyJet Traveller is unique in today’s advertising environment, not only 3-5% every year (IATA) because of its increasing audience, but also because we have a deep understanding of who is travelling, as well as where and when. Passengers love us for always being Passenger numbers will double in the positive, aspirational and inspiring. next 20 years (IATA) 74% of passengers read inflight magazines (Kantar TGI) Travel media has the most affluent readership of any of the world’s media (Gfk MRI) Travellers are 50% more engaged reading inflight than when on the ground (Ink: A Flight to Remember) Inflight media isalways inspiring and positive Travel media reaches real people without being a digital distraction All travel media is targeted Ink is the largest travel media company in the world. We make unrivalled award-winning content Contact Phil Castle [email protected] +44 20 7625 0922 Why easyJet? easyJet expects to fly 100m passengers this year on 1,055 routes across 37 countries, In numbers 100m making it officially the UK’s largest airline and the second largest in the world by passengers a year international passengers. -

AWARD-WINNING No

AWARD-WINNING No. 95 Autumn 2012 www.camrabristol.org.uk INTS WES Multi-award-winning magazine of the Bristol & District Branch of CAMRA, the Campaign for Real Ale P (incorporating the Bath & Borders Branch) T PINTS WEST The fight to save your pint continues A open letter to Chloe Smith MP, economic secretary to the Treasury Dear Chloe Smith How many more pubs do you want to see close? I was prompted to ask escalator, you are forcing pubs to close. Your prime minister believes in the the question following your intervention in a debate in parliament this Big Society but such a society will wither on the vine if pubs, at the heart of month when MPs representing constituencies with breweries raised their their communities, go out of business. concerns about high levels of beer duty. Both your prime minster and home secretary have encouraged people to Andrew Griffi ths, the member for Burton and chairman of the Parlia- drink in pubs, where alcohol is consumed moderately and sensibly. But it’s mentary Beer Group, singled out the particular problem of the beer duty a hollow objective if pubs are driven out of business as a result of ruinous escalator, which automatically increases duty in the annual budget without levels of duty and VAT. recourse to parliament. Beer taxation is not “reasonable”, Miss Smith. on the contrary, it’s kill- Your reply was breathtaking. “The duty increase forms a vital part of ing the British pub. It’s time for a U-turn. the government’s plan to tackle the debt left by the previous government. -

CORONA BELEID Stadsbrouwerij De Maastrichter Maltezer

CORONA BELEID Stadsbrouwerij de Maastrichter Maltezer Dear guest, How wonderful to welcome you all again in our beautiful establishment! We were all very shocked off what the corona virus, COVID 19, did to our world. We want to keep all of our guests and our team healthy and safe. That's why we have a couple of rules we all need to follow, so we can make sure everyone stays healthy and safe in these weird times. There are basic rules for everyone, like no hand-shaking, sneeze and coughing in the elbow and often washing your hands, Further measures that we will take to ensure everyones health and safety are; Reservations are required to ensure a seat in our "proeflokaal"! A health check will take place on arrival. A maximum of 2 people sit at a table or bar unless it is a shared household consisting of more people. Washing hands upon entry and after visiting the toilet is mandatory, several stations have been set up for this in our establishment. Posters in various places in our "proeflokaal" and on the terrace indicate which steps need to be taken before we can place you at a table. We ask our guests to make payments by card, we will disinfect our machines regularly. Our "proeflokaal" and terrace are arranged in such a way that the current setup guarantees the 1.5 meter regulation. We ask our guests not to shuffle with our tables and chairs. Our team remains aware of the consequences, if someone shows symptoms, the person stays at home. -

What Is a Cicerone? the First Exam Assesses Knowledge Only and Is Given Online

What is a Cicerone? The first exam assesses knowledge only and is given online. The exams for Certified Cicerone® and The word Cicerone (pronounced Master Cicerone® supplement the written exam with sis-uh-rohn) designates those with tasting questions and demonstrations of hands-on proven expertise in selecting, acquiring knowledge related to beer service. Exam locations and serving today’s wide range of are announced at http://cicerone.org. beers. The titles “Certified Cicerone®” and “Master Cicerone®” are protected To ensure that consumers receive and enjoy certification trademarks. Only those top quality beer service, the program assesses who have passed the requisite test of knowledge in five areas: knowledge and tasting skill can call Keeping & Serving Beer themselves a Cicerone. Beer Styles Beer Tasting and Flavors To encourage participation by Brewing Ingredients and Processes everyone from recently hired servers Pairing Beer with Food to veteran experts, the program offers three levels of certification beginning The Cicerone Certification Program® draws from with fundamentals and building these five subject areas for each of its exams. The to broad and in-depth knowledge actual knowledge required for each exam is outlined supplemented by extensive exper- in a syllabus that can be accessed and viewed at ience. The three levels are: http://cicerone.org. The first level exam focuses on Keeping & Serving Beer and key beer styles with 1. Certified Beer Server a smaller emphasis on the other three areas. The 2. Certified Cicerone® Novice Syllabus details the knowledge required for 3. Master Cicerone® Certified Beer Server. Who Takes the Cicerone Exams? Beer distributors: sales representatives and sales How is a Cicerone different from a Beer More than 5,000 beer professionals management, technical beer specialists. -

CRAFT BREWERS BASHED by OUR WINDS PRODUCE FOOD NI PRODUCERS 2016 GUIDE @Food NI

We Catch We EnjoyWe Craft We We Breed Grow The People Who Rear, Grow and Make Our Great Local Produce Local Our Great and Make Grow Who Rear, The People e We W Cook Catch HOOKED AND COOKED HERE BORN FOOD &BRED BAKERS BLENDERS &BREWERS Food NI Producers 2016 Guide NI Producers Food LOCALBUTCHERS LUSH PASTURES FARMERS GREAT GRASS ROOTS & SHOOTS Food NI Limited PEOPLE Belfast Mills Tel: +44 (0)28 9024 9449 GROWERS MAKING 71-75 Percy Street Email: [email protected] Belfast, BT13 2HW Web: www.nigoodfood.com LASHED BY OUR RAIN, GREAT @Food_NI CRAFT BREWERS BASHED BY OUR WINDS PRODUCE FOOD NI PRODUCERS 2016 GUIDE @Food_NI #nifood16 #nidrink16 #enjoyni16 #ourfoodsogood Supported by the NORTHERN IRELAND REGIONAL FOOD PROGRAMME 2016 Food NI Producers Guide Who we are Thanks for picking up this booklet. In case you’re wondering who’s behind it, let us tell you. We are Food NI/Taste of Ulster. We’re all about showcasing the finest food and drink from Northern Ireland. We promote the people who produce it and distribute it to shops and catering outlets. We believe we have world-class ingredients and chefs and we work tirelessly to get that message out near and far. Our producer members represent everyone from the small artisan to the large scale distributors. We have the full support of the Northern Ireland agri-food industry. Our board of directors include all the major stakeholders. We’re constantly in touch with the media, telling them about what are members are doing. Every week we are letting know about awards that have been won and new products that have hit the shelves. -

Viti Wine and Lager

the PublicanThe Alliance of Beverage Licensees Winter 2012 Viti Wine and Lager International Beer Styles Wine Clubs: Expanding the Wine Culture Building Your Brand Options in Glassware 40026059 # AGREEMENT AGREEMENT The official comfort beer of Winter is here. WORLD BEER CHAMPIONSHIPS GIB-C19640_MovemberBackerCard.indd 2 11-08-30 12:15 PM Wasserman + Partners advertising Art: lm AE: mh Dsgn: gj proD: sh CmYK Laser % trim sizE: 12" x 21" prEss / stock: offset giB-C19640.02 BlEED: .125" rEs finishED: 300 ppi DEsign : file: giB-c19640_movemberBackercard othEr: - Artwork scAlE: 1 : 1 rev: Aug. 30, 2011 – 12:14 pm finishED: - rEs Artwork: 300 PPi AE/proD : movember Backer Card formAt: inDesign cs5 notE : BaCK DElivEr: collect traP at OutPut stuDio : On the Cover Ralf Joneikies Viti Wine and Lager Quarterly Publication for the Alliance of Beverage Licensees 2nd floor 948 Howe Street, Vancouver, BC V6Z 1N9 T 604-688-5560 F 604-688-8560 Toll free 1-800-663-4883 24 [email protected] www.ablebc.ca 2011-2012 Board of Directors President Ron Orr (Interim) Past President Al Arbuthnot VP Membership Jonathan Cross VP LP Poma Dhaliwal VP Governance John Lepinski VP LRS Ron Orr 12 18 26 30 Secretary/Treasurer Roger Gibson Executive Director Ian Baillie Directors Brady Beruschi, Al Deacon, Mariana Fiddler, the Al McCreary, Mike McKee, Gavin Parry, Ronnie Paterson, Kurt Pyrch, Danny Rickaby, Stan Sprenger Director at Large Dave Crown The Publican Editorial Committee Damian Kettlewell, Ralf Joneikies, Mike McKee, Gary McPhail, PublicanWinter2012 Ron Orr, Brian -

PRESS RELEASE October 2016

PRESS RELEASE October 2016 From the traditional double bock to the Pale Ale with black truffle Craft Beer Corner showing a diversity of craft beers Enjoyment and passion the focal point It will once again be the visitor attraction at BrauBeviale from 8 to 10 November. And a good source of inspiration for restaurateurs/caterers, retailers and brewers: the Craft Beer Corner. This year, even larger and more diverse, it will be presenting itself in Hall 9. Over 250 craft beers from 20 countries will be tasted there every day by beer sommeliers. The success formula for the Craft Beer Corner: the infectious enthusiasm and passion for craft beer with an exceptional flavour. The beer sommeliers, Klaus Artmann and David Hertl, report on their personal experience. “You anticipate it, then close your eyes and simply just enjoy”, this is how Klaus Artmann, Managing Director of exbierience GmbH, specialized in special beer events, describes the moment of tasting beer. He was already standing behind one of the bars last year in the Craft Beer Corner as a trained beer sommelier. “Don’t get the wrong impression: in contrast to the Octoberfest, here it is about taking just a small sip of each beer and for that reason great attention is paid to we have drunk”, said Artmann. He wishes to familiarize the visitors with the story behind the beer. To this end, he prepares himself well in the run-up to the event. Initially, he obtains basic information from the label and the Internet, then he holds a detailed discussion with the master brewer about the ingredients used, the malt refinement, the hops treatment or the maturing period and ultimately, forms of course his own impression of the special amber nectar.