10 the Relations Between the EU and Andorra, San Marino and Monaco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of San Marino

History of San Marino The official date of the foundation of the Republic of San Marino is AD 3 September 301. Legend states that a Christian stonecutter named Marinus escaped persecution from the Roman emperor Diocletian by sailing from the Croatian island of Arbe across the Adriatic Sea to Rimini. Marinus became a hermit, taking up residency on Monte Titano, where he built up a Christian community. He was later canonized andthe land renamed in his honor. Throughout the Middle Ages, the tiny territory made alliances and struggled to remain intact as a string of feudal lords attempted to conquer it in their attempts to control the Papal States. On 27 June 1463, Pope Pio II gave San Marino the castles of Serravalle, Fiorentino, and Montegiardino. The castle Faetano voluntarily joined later that year, increasing San Marino’s boundaries to their present size. In 1503, Cesare Borgia managed to conquer and rule San Marino for six months. In 1739, Cardinal Alberoni’s troops occupied San Marino. After many protests, the Pope sent Monsignor Enrico Enriquez to investigate the legality of Alberoni’s occupation, and San Marino subsequently regained its independence on St. Agatha’s day, now a national holiday. In 1797, Napoleon invaded the Italian peninsula. Reaching Rimini, he stopped short of San Marino, praising it as a model of republican liberty. San Marino declined his offer to extend its lands to the Adriatic Sea. With the fall of Napoleon, San Marino was recognized as an independent state, adopting the motto Nemini Teneri (Not dependent upon anyone). San Marino remains neutral in wartime, but many Sammarinese volunteered in the Italian Army during World War I. -

San Marino Legal E

Study on Homophobia, Transphobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Legal Report: San Marino 1 Disclaimer: This report was drafted by independent experts and is published for information purposes only. Any views or opinions expressed in the report are those of the author and do not represent or engage the Council of Europe or the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights. 1 This report is based on Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino , University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010. The latter report is attached to this report. Table of Contents A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 B. FINDINGS 3 B.1. Overall legal framework 3 B.2. Freedom of Assembly, Association and Expression 10 B.3. Hate crime - hate speech 10 B.4. Family issues 13 B.5. Asylum and subsidiary protection 16 B.6. Education 17 B.7. Employment 18 B.8. Health 20 B.9. Housing and Access to goods and services 21 B.10. Media 22 B.11. Transgender issues 23 Annex 1: List of relevant national laws 27 Annex 2: Report of Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino, University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010 31 A. Executive Summary 1. The Statutes "Leges Statuae Reipublicae Sancti Marini" that came into force in 1600 and the Laws that reform such Statutes represented the written source for excellence of the Sammarinese legal system. -

Urban Society and Communal Independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy

Urban society and communal independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy Paul Oldfield Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD. The University of Leeds The School of History September 2006 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks for the help of so many different people, without which there would simply have been no thesis. The funding of the AHRC (formerly AHRB) and the support of the School of History at the University of Leeds made this research possible in the first place. I am grateful too for the general support, and advice on reading and sources, provided by Dr. A. J. Metcalfe, Dr. P. Skinner, Professor E. Van Houts, and Donald Matthew. Thanks also to Professor J-M. Martin, of the Ecole Francoise de Rome, for his continual eagerness to offer guidance and to discuss the subject. A particularly large thanks to Mr. I. S. Moxon, of the School of History at the University of Leeds, for innumerable afternoons spent pouring over troublesome Latin, for reading drafts, and for just chatting! Last but not least, I am hugely indebted to the support, understanding and endless efforts of my supervisor Professor G. A. Loud. His knowledge and energy for the subject has been infectious, and his generosity in offering me numerous personal translations of key narrative and documentary sources (many of which are used within) allowed this research to take shape and will never be forgotten. -

Reichskommissariat Ukraine from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Reichskommissariat Ukraine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia During World War II, Reichskommissariat Ukraine (abbreviated as RKU), was the civilian Navigation occupation regime of much of German-occupied Ukraine (which included adjacent areas of Reichskommissariat Ukraine Main page modern Belarus and pre-war Poland). Between September 1941 and March 1944, the Reichskommissariat of Germany Contents Reichskommissariat was administered by Reichskommissar Erich Koch. The ← → Featured content administration's tasks included the pacification of the region and the exploitation, for 1941–1944 Current events German benefit, of its resources and people. Adolf Hitler issued a Führer Decree defining Random article the administration of the newly occupied Eastern territories on 17 July 1941.[1] Donate to Wikipedia Before the German invasion, Ukraine was a constituent republic of the USSR, inhabited by Ukrainians with Russian, Polish, Jewish, Belarusian, German, Roma and Crimean Tatar Interaction minorities. It was a key subject of Nazi planning for the post-war expansion of the German Flag Emblem state and civilization. Help About Wikipedia Contents Community portal 1 History Recent changes 2 Geography Contact Wikipedia 3 Administration 3.1 Political figures related with the German administration of Ukraine Toolbox 3.2 Military commanders linked with the German administration of Ukraine 3.3 Administrative divisions What links here 3.3.1 Further eastward expansion Capital Rowno (Rivne) Related changes 4 Demographics Upload file Languages German (official) 5 Security Ukrainian Special pages 6 Economic exploitation Polish · Crimean Tatar Permanent link 7 German intentions Government Civil administration Page information 8 See also Reichskommissar Data item 9 References - 1941–1944 Erich Koch Cite this page 10 Further reading Historical era World War II 11 External links - Established 1941 Print/export - Disestablished 1944 [edit] Create a book History Download as PDF Population This section requires expansion. -

A Viking-Age Settlement in the Hinterland of Hedeby Tobias Schade

L. Holmquist, S. Kalmring & C. Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.), New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17-20th 2013. Theses and Papers in Archaeology B THESES AND PAPERS IN ARCHAEOLOGY B New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17–20th 2013 Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.) Contents Introduction Sigtuna: royal site and Christian town and the Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & regional perspective, c. 980-1100 Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson.....................................4 Sten Tesch................................................................107 Sigtuna and excavations at the Urmakaren Early northern towns as special economic and Trädgårdsmästaren sites zones Jonas Ros.................................................................133 Sven Kalmring............................................................7 No Kingdom without a town. Anund Olofs- Spaces and places of the urban settlement of son’s policy for national independence and its Birka materiality Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson...................................16 Rune Edberg............................................................145 Birka’s defence works and harbour - linking The Schleswig waterfront - a place of major one recently ended and one newly begun significance for the emergence of the town? research project Felix Rösch..........................................................153 -

EU Law WP 51 Lopez Cover

Stanford – Vienna Transatlantic Technology Law Forum A joint initiative of Stanford Law School and the University of Vienna School of Law European Union Law Working Papers No. 51 San Marino: Navigating the European Union as a Microstate Thomas W. Lopez 2021 European Union Law Working Papers Editors: Siegfried Fina and Roland Vogl About the European Union Law Working Papers The European Union Law Working Paper Series presents research on the law and policy of the European Union. The objective of the European Union Law Working Paper Series is to share “works in progress”. The authors of the papers are solely responsible for the content of their contributions and may use the citation standards of their home country. The working papers can be found at http://ttlf.stanford.edu. The European Union Law Working Paper Series is a joint initiative of Stanford Law School and the University of Vienna School of Law’s LLM Program in European and International Business Law. If you should have any questions regarding the European Union Law Working Paper Series, please contact Professor Dr. Siegfried Fina, Jean Monnet Professor of European Union Law, or Dr. Roland Vogl, Executive Director of the Stanford Program in Law, Science and Technology, at: Stanford-Vienna Transatlantic Technology Law Forum http://ttlf.stanford.edu Stanford Law School University of Vienna School of Law Crown Quadrangle Department of Business Law 559 Nathan Abbott Way Schottenbastei 10-16 Stanford, CA 94305-8610 1010 Vienna, Austria About the Author Thomas W. Lopez is a J.D. candidate at Stanford Law School. He earned his bachelor’s degree in History from Yale University in 2019. -

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 3. Quartal 1999

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 3. Quartal 1999 Geschichte: Einführungen.........................................................................................................................................................2 Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtstheorie........................................................................................................................2 Historische Hilfswissenschaften..............................................................................................................................................7 Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, Geschichte der Entdeckungen, Geschichte der Weltkriege ...........................................11 Alte Geschichte.........................................................................................................................................................................19 Europäische Geschichte in Mittelalter und Neuzeit............................................................................................................22 Deutsche Geschichte................................................................................................................................................................26 Geschichte der deutschen Laender und Staedte..................................................................................................................37 Geschichte der Schweiz, Österreichs, Ungarns, Tschechiens und der Slowakei...........................................................48 Geschichte Skandinaviens ......................................................................................................................................................50 -

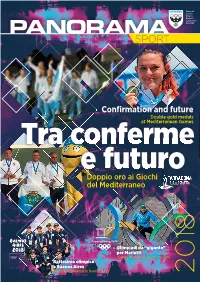

Confirmation and Future

Rivista del Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Sammarinese Anno 2018 SPORT Confirmation and future Double gold medals at Mediterranean Games 2018 SPORT Tra conferme PANORAMA PANORAMA e futuro Doppio oro ai Giochi del Mediterraneo Olimpiadi da “gigante” per Mariotti “Giant” Winter Games for Mariotti Battesimo olimpico a Buenos Aires C.O.N.S. Olympic experience in Buenos Aires 2018 Behind every great team is a great team. Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Sammarinese San Marino Olympic Partners Get involved at olympicchannel.com/light Direttore Editoriale Gian Primo Giardi Direttore Responsabile 10 14 20 30 Eros Bologna Coordinamento Ufficio Stampa CONS Testi Elisa Gianessi Uffici stampa federali Fotografie Alan Gasperoni Claudio Stefanelli Archivio CONS Archivi federali Michael Felici IOC LIBRARY Direzione e redazione Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Sammarinese Via Rancaglia 30 47899 – Serravalle Repubblica di San Marino Con la collaborazione di Rossana Ferri Alan Gasperoni Sommario Bruno Gennari Traduzioni 2018 Elledue-Assistenza linguistica srl 2 6 8 10 Stampa Focus sui giovani Un 2018 di grandi In mezzo al guado Per Mariotti Arti Grafiche Della Balda e coinvolgimento delle traguardi. Fissate già le un’Olimpiade donne per continuare prossime sfide da “gigante” a vincere 13 14 20 24 I prossimi appuntamenti Tarragona 2018, Quattro moschettieri La vision del Nado una storica a Buenos Aires San Marino: “Praticare doppietta d’oro lo sport in modo pulito e salutare, libero 28 30 32 36 Un pieno di sport San Marino 2017 Amarcord L’angolo del collezionista a -

PDF) 978-3-11-066078-4 E-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-065796-8

The Crisis of the 14th Century Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 13 The Crisis of the 14th Century Teleconnections between Environmental and Societal Change? Edited by Martin Bauch and Gerrit Jasper Schenk Gefördert von der VolkswagenStiftung aus den Mitteln der Freigeist Fellowship „The Dantean Anomaly (1309–1321)“ / Printing costs of this volume were covered from the Freigeist Fellowship „The Dantean Anomaly 1309-1321“, funded by the Volkswagen Foundation. Die frei zugängliche digitale Publikation wurde vom Open-Access-Publikationsfonds für Monografien der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft gefördert. / Free access to the digital publication of this volume was made possible by the Open Access Publishing Fund for monographs of the Leibniz Association. Der Peer Review wird in Zusammenarbeit mit themenspezifisch ausgewählten externen Gutachterin- nen und Gutachtern sowie den Beiratsmitgliedern des Mediävistenverbands e. V. im Double-Blind-Ver- fahren durchgeführt. / The peer review is carried out in collaboration with external reviewers who have been chosen on the basis of their specialization as well as members of the advisory board of the Mediävistenverband e.V. in a double-blind review process. ISBN 978-3-11-065763-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-066078-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-065796-8 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019947596 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Application of Link Integrity Techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Department of Electronics and Computer Science A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD Supervisor: Prof. Wendy Hall and Dr Les Carr Examiner: Dr Nick Gibbins Application of Link Integrity techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web by Rob Vesse February 10, 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD by Rob Vesse As the Web of Linked Data expands it will become increasingly important to preserve data and links such that the data remains available and usable. In this work I present a method for locating linked data to preserve which functions even when the URI the user wishes to preserve does not resolve (i.e. is broken/not RDF) and an application for monitoring and preserving the data. This work is based upon the principle of adapting ideas from hypermedia link integrity in order to apply them to the Semantic Web. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hypothesis . .2 1.2 Report Overview . .8 2 Literature Review 9 2.1 Problems in Link Integrity . .9 2.1.1 The `Dangling-Link' Problem . .9 2.1.2 The Editing Problem . 10 2.1.3 URI Identity & Meaning . 10 2.1.4 The Coreference Problem . 11 2.2 Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1 Early Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1.1 Halasz's 7 Issues . 12 2.2.2 Open Hypermedia . 14 2.2.2.1 Dexter Model . 14 2.2.3 The World Wide Web . -

Genocide Studies and Prevention: an International Journal

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 13 Issue 1 Revisiting the Life and Work of Raphaël Article 2 Lemkin 4-2019 Full Issue 13.1 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation (2019) "Full Issue 13.1," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 13: Iss. 1: 1-203. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.13.1 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol13/iss1/2 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 1911-0359 eISSN 1911-9933 Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 13.1 - 2019 ii ©2019 Genocide Studies and Prevention 13, no. 1 iii Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/ Volume 13.1 - 2019 Editorials Christian Gudehus, Susan Braden, Douglas Irvin-Erickson, JoAnn DiGeorgio-Lutz, and Lior Zylberman Editors’ Introduction ................................................................................................................1 Benjamin Meiches and Jeff Benvenuto Guest Editorial: Between Hagiography and Wounded Attachment: Raphaël Lemkin and the Study of Genocide ...............................................................................................................2 Articles Jonathan -

RELIGION and COVID19 in SAN MARINO|W – 3 April 2020

Papers The Republic of San Marino and the practice of worship in the Covid-19 era: between history, common law and emergency decrees by Antonello De Oto* [email protected] 1. The disease of 1855 and the emergency "notification" in San Marino yesterday as today. Only a few years after Garibaldi’s “escape” in San Marino, where the hero of the two worlds found hospitality hunted by the Austrians in the most serious hour1, a new fearful danger for the survival of the oldest Republic in the world * Associate Professor of Italian and Comparative Ecclesiastical Law and Law of Religions - Alma Mater Studiorum - University of Bologna. 1 On the morning of July 31, 1849 the torn, hungry and tired Garibaldini, pursued by four armies, decided to violate the border of the Republic of San Marino. After exchanging a few words with the Barnabite friar Ugo Bassi, the Hero of Two Worlds, who had arrived in the city, he immediately went to the Government Palace where he explained the painful situation 1 RELIGION AND COVID19 IN SAN MARINO|wwww.diresom.net – 3 April 2020 Papers loomed on the horizon. This time it was not the fear of being invaded by the weapons of others, but a subtle and invisible enemy that crossed the borders without showing any documents, just the disease that in 1855 arrived on the Titan, just as today the Coranavirus, silent and deadly, crosses the doors of the Serenissima Republic bringing infection and death. The “Asian disease” that appeared in 1855 in the small State forced the Captains Regent of that time to produce (yesterday as today) an emergency decree on several occasions in an attempt to contain the infection.