De Syon Exierit Lex Et Verbum Domini De Iherusalem’: an Exegetical Discourse (C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hérésies : Une Construction D’Identités Religieuses

Hérésies : une construction d’identités religieuses Quelles sortes de communautés réunissent les hommes ? Comment sont- elles construites ? Où est l’unité, où est la multiplicité de l’humanité ? Les hommes peuvent former des communautés distinctes, antagonistes, s’opposant violemment. La division externe est-elle nécessaire pour bâtir une cohésion interne ? Rien n’est plus actuel que ces questions. Parmi toutes ces formes de dissensions, les études qui composent ce volume s’intéressent à l’hérésie. L’hérésie se caractérise par sa relativité. Nul ne se revendique hérétique, sinon par provocation. Le qualificatif d’hérétique est toujours subi par celui qui le porte et il est toujours porté DYE BROUWER, GUILLAUME CHRISTIAN PAR EDITE ROMPAEY VAN ET ANJA Hérésies : une construction sur autrui. Cela rend l’hérésie difficilement saisissable si l’on cherche ce qu’elle est en elle-même. Mais le phénomène apparaît avec davantage de clarté si l’on analyse les discours qui l’utilisent. Se dessinent dès lors les d’identités religieuses représentations qui habitent les auteurs de discours sur l’hérésie et les hérétiques, discours généralement sous-tendus par une revendication à EDITE PAR CHRISTIAN BROUWER, GUILLAUME DYE ET ANJA VAN ROMPAEY l’orthodoxie. Hérésie et orthodoxie forment ainsi un couple, désuni mais inséparable. Car du point de vue de l’orthodoxie, l’hérésie est un choix erroné, une déviation, voire une déviance. En retour, c’est bien parce qu’un courant se proclame orthodoxe que les courants concurrents peuvent être accusés d’hérésie. Sans opinion correcte, pas de choix déviant. La thématique de l’hérésie s’inscrit ainsi dans les questions de recherche sur l’altérité religieuse. -

History of San Marino

History of San Marino The official date of the foundation of the Republic of San Marino is AD 3 September 301. Legend states that a Christian stonecutter named Marinus escaped persecution from the Roman emperor Diocletian by sailing from the Croatian island of Arbe across the Adriatic Sea to Rimini. Marinus became a hermit, taking up residency on Monte Titano, where he built up a Christian community. He was later canonized andthe land renamed in his honor. Throughout the Middle Ages, the tiny territory made alliances and struggled to remain intact as a string of feudal lords attempted to conquer it in their attempts to control the Papal States. On 27 June 1463, Pope Pio II gave San Marino the castles of Serravalle, Fiorentino, and Montegiardino. The castle Faetano voluntarily joined later that year, increasing San Marino’s boundaries to their present size. In 1503, Cesare Borgia managed to conquer and rule San Marino for six months. In 1739, Cardinal Alberoni’s troops occupied San Marino. After many protests, the Pope sent Monsignor Enrico Enriquez to investigate the legality of Alberoni’s occupation, and San Marino subsequently regained its independence on St. Agatha’s day, now a national holiday. In 1797, Napoleon invaded the Italian peninsula. Reaching Rimini, he stopped short of San Marino, praising it as a model of republican liberty. San Marino declined his offer to extend its lands to the Adriatic Sea. With the fall of Napoleon, San Marino was recognized as an independent state, adopting the motto Nemini Teneri (Not dependent upon anyone). San Marino remains neutral in wartime, but many Sammarinese volunteered in the Italian Army during World War I. -

San Marino Legal E

Study on Homophobia, Transphobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Legal Report: San Marino 1 Disclaimer: This report was drafted by independent experts and is published for information purposes only. Any views or opinions expressed in the report are those of the author and do not represent or engage the Council of Europe or the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights. 1 This report is based on Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino , University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010. The latter report is attached to this report. Table of Contents A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 B. FINDINGS 3 B.1. Overall legal framework 3 B.2. Freedom of Assembly, Association and Expression 10 B.3. Hate crime - hate speech 10 B.4. Family issues 13 B.5. Asylum and subsidiary protection 16 B.6. Education 17 B.7. Employment 18 B.8. Health 20 B.9. Housing and Access to goods and services 21 B.10. Media 22 B.11. Transgender issues 23 Annex 1: List of relevant national laws 27 Annex 2: Report of Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino, University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010 31 A. Executive Summary 1. The Statutes "Leges Statuae Reipublicae Sancti Marini" that came into force in 1600 and the Laws that reform such Statutes represented the written source for excellence of the Sammarinese legal system. -

Urban Society and Communal Independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy

Urban society and communal independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy Paul Oldfield Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD. The University of Leeds The School of History September 2006 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks for the help of so many different people, without which there would simply have been no thesis. The funding of the AHRC (formerly AHRB) and the support of the School of History at the University of Leeds made this research possible in the first place. I am grateful too for the general support, and advice on reading and sources, provided by Dr. A. J. Metcalfe, Dr. P. Skinner, Professor E. Van Houts, and Donald Matthew. Thanks also to Professor J-M. Martin, of the Ecole Francoise de Rome, for his continual eagerness to offer guidance and to discuss the subject. A particularly large thanks to Mr. I. S. Moxon, of the School of History at the University of Leeds, for innumerable afternoons spent pouring over troublesome Latin, for reading drafts, and for just chatting! Last but not least, I am hugely indebted to the support, understanding and endless efforts of my supervisor Professor G. A. Loud. His knowledge and energy for the subject has been infectious, and his generosity in offering me numerous personal translations of key narrative and documentary sources (many of which are used within) allowed this research to take shape and will never be forgotten. -

Origen in the Likeness of Philo: Eusebius of Caesarea's Portrait Of

SCJR 12, no. 1 (2017): 1-13 Origen in the Likeness of Philo: Eusebius of Caesarea’s Portrait of the Model Scholar JUSTIN M. ROGERS [email protected] Freed-Hardeman University, Henderson, TN 38340 The name of Philo of Alexandria occurs more in the writings of Eusebius of Caesarea than in those of any other ancient author. Philo’s name can be located over 20 times in the surviving literary corpus of Eusebius,1 and there is strong ev- idence that Eusebius’ Caesarean library is the very reason Philo’s works exist today.2 In all probability, the core of this library can be traced to the personal col- lection of Origen when he settled in Caesarea in 232 CE.3 Eusebius’ own teacher Pamphilus expanded the library, and took great pains to copy and preserve Ori- gen’s own works. What we have, then, is a literary union between Philo and Origen, Alexandrians within the same exegetical tradition. But we can go further. Ilaria Ramelli has argued that Eusebius’ accounts of Philo and Origen in the Ecclesiastical History are strikingly similar, picking up Robert Grant’s stress on the similarity between Origen and the Philonic Therapeutae.4 Here, I further Ramelli’s work by noting additional similarities in the Eusebian biographical presentations. I also point to the tension Eusebius felt between Philo Christianus and Philo Judaeus, a tension detectible in his presentation of the Therapeutae, a group about whom Philo reported and whom Eusebius considered to be the first Egyptian Christians.5 The result is that Eusebius recognized Philo to be exegeti- cally closer to Christianity, and religiously closer to Judaism. -

Reichskommissariat Ukraine from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Reichskommissariat Ukraine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia During World War II, Reichskommissariat Ukraine (abbreviated as RKU), was the civilian Navigation occupation regime of much of German-occupied Ukraine (which included adjacent areas of Reichskommissariat Ukraine Main page modern Belarus and pre-war Poland). Between September 1941 and March 1944, the Reichskommissariat of Germany Contents Reichskommissariat was administered by Reichskommissar Erich Koch. The ← → Featured content administration's tasks included the pacification of the region and the exploitation, for 1941–1944 Current events German benefit, of its resources and people. Adolf Hitler issued a Führer Decree defining Random article the administration of the newly occupied Eastern territories on 17 July 1941.[1] Donate to Wikipedia Before the German invasion, Ukraine was a constituent republic of the USSR, inhabited by Ukrainians with Russian, Polish, Jewish, Belarusian, German, Roma and Crimean Tatar Interaction minorities. It was a key subject of Nazi planning for the post-war expansion of the German Flag Emblem state and civilization. Help About Wikipedia Contents Community portal 1 History Recent changes 2 Geography Contact Wikipedia 3 Administration 3.1 Political figures related with the German administration of Ukraine Toolbox 3.2 Military commanders linked with the German administration of Ukraine 3.3 Administrative divisions What links here 3.3.1 Further eastward expansion Capital Rowno (Rivne) Related changes 4 Demographics Upload file Languages German (official) 5 Security Ukrainian Special pages 6 Economic exploitation Polish · Crimean Tatar Permanent link 7 German intentions Government Civil administration Page information 8 See also Reichskommissar Data item 9 References - 1941–1944 Erich Koch Cite this page 10 Further reading Historical era World War II 11 External links - Established 1941 Print/export - Disestablished 1944 [edit] Create a book History Download as PDF Population This section requires expansion. -

A Viking-Age Settlement in the Hinterland of Hedeby Tobias Schade

L. Holmquist, S. Kalmring & C. Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.), New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17-20th 2013. Theses and Papers in Archaeology B THESES AND PAPERS IN ARCHAEOLOGY B New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17–20th 2013 Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.) Contents Introduction Sigtuna: royal site and Christian town and the Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & regional perspective, c. 980-1100 Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson.....................................4 Sten Tesch................................................................107 Sigtuna and excavations at the Urmakaren Early northern towns as special economic and Trädgårdsmästaren sites zones Jonas Ros.................................................................133 Sven Kalmring............................................................7 No Kingdom without a town. Anund Olofs- Spaces and places of the urban settlement of son’s policy for national independence and its Birka materiality Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson...................................16 Rune Edberg............................................................145 Birka’s defence works and harbour - linking The Schleswig waterfront - a place of major one recently ended and one newly begun significance for the emergence of the town? research project Felix Rösch..........................................................153 -

Pythagorean, Predecessor, and Hebrew: Philo of Alexandria and the Construction of Jewishness in Early Christian Writings

Pythagorean, Predecessor, and Hebrew: Philo of Alexandria and the Construction of Jewishness in Early Christian Writings Jennifer Otto Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University, Montreal March, 2014 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Jennifer Otto, 2014 ii Table of Contents Abstracts v Acknowledgements vii Abbreviations viii Introduction 1 Method, Aims and Scope of the Thesis 10 Christians and Jews among the nations 12 Philo and the Wisdom of the Greeks 16 Christianity as Philosophy 19 Moving Forward 24 Part I Chapter 1: Philo in Modern Scholarship 25 Introducing Philo 25 Philo the Jew in modern research 27 Conclusions 48 Chapter 2: Sects and Texts: The Setting of the Christian Encounter with Philo 54 The Earliest Alexandrian Christians 55 The Trajanic Revolt 60 The “Catechetical School” of Alexandria— A Continuous 63 Jewish-Christian Institution? An Alternative Hypothesis: Reading Philo in the Philosophical Schools 65 Conclusions 70 Part II Chapter 3: The Pythagorean: Clement’s Philo 72 1. Introducing Clement 73 1.1 Clement’s Life 73 1.2 Clement’s Corpus 75 1.3 Clement’s Teaching 78 2. Israel, Hebrews, and Jews in Clement’s Writings 80 2.1 Israel 81 2.2 Hebrews 82 2.3 Jews 83 3. Clement’s Reception of Philo: Literature Review 88 4. Clement’s Testimonia to Philo 97 4.1 Situating the Philonic Borrowings in the context of Stromateis 1 97 4.2 Stromateis 1.5.31 102 4.3 Stromateis 1.15.72 106 4.4 Stromateis 1.23.153 109 iii 4.5 Situating the Philonic Borrowings in the context of Stromateis 2 111 4.6 Stromateis 2.19.100 113 5. -

EU Law WP 51 Lopez Cover

Stanford – Vienna Transatlantic Technology Law Forum A joint initiative of Stanford Law School and the University of Vienna School of Law European Union Law Working Papers No. 51 San Marino: Navigating the European Union as a Microstate Thomas W. Lopez 2021 European Union Law Working Papers Editors: Siegfried Fina and Roland Vogl About the European Union Law Working Papers The European Union Law Working Paper Series presents research on the law and policy of the European Union. The objective of the European Union Law Working Paper Series is to share “works in progress”. The authors of the papers are solely responsible for the content of their contributions and may use the citation standards of their home country. The working papers can be found at http://ttlf.stanford.edu. The European Union Law Working Paper Series is a joint initiative of Stanford Law School and the University of Vienna School of Law’s LLM Program in European and International Business Law. If you should have any questions regarding the European Union Law Working Paper Series, please contact Professor Dr. Siegfried Fina, Jean Monnet Professor of European Union Law, or Dr. Roland Vogl, Executive Director of the Stanford Program in Law, Science and Technology, at: Stanford-Vienna Transatlantic Technology Law Forum http://ttlf.stanford.edu Stanford Law School University of Vienna School of Law Crown Quadrangle Department of Business Law 559 Nathan Abbott Way Schottenbastei 10-16 Stanford, CA 94305-8610 1010 Vienna, Austria About the Author Thomas W. Lopez is a J.D. candidate at Stanford Law School. He earned his bachelor’s degree in History from Yale University in 2019. -

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 3. Quartal 1999

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 3. Quartal 1999 Geschichte: Einführungen.........................................................................................................................................................2 Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtstheorie........................................................................................................................2 Historische Hilfswissenschaften..............................................................................................................................................7 Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, Geschichte der Entdeckungen, Geschichte der Weltkriege ...........................................11 Alte Geschichte.........................................................................................................................................................................19 Europäische Geschichte in Mittelalter und Neuzeit............................................................................................................22 Deutsche Geschichte................................................................................................................................................................26 Geschichte der deutschen Laender und Staedte..................................................................................................................37 Geschichte der Schweiz, Österreichs, Ungarns, Tschechiens und der Slowakei...........................................................48 Geschichte Skandinaviens ......................................................................................................................................................50 -

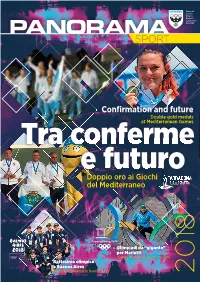

Confirmation and Future

Rivista del Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Sammarinese Anno 2018 SPORT Confirmation and future Double gold medals at Mediterranean Games 2018 SPORT Tra conferme PANORAMA PANORAMA e futuro Doppio oro ai Giochi del Mediterraneo Olimpiadi da “gigante” per Mariotti “Giant” Winter Games for Mariotti Battesimo olimpico a Buenos Aires C.O.N.S. Olympic experience in Buenos Aires 2018 Behind every great team is a great team. Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Sammarinese San Marino Olympic Partners Get involved at olympicchannel.com/light Direttore Editoriale Gian Primo Giardi Direttore Responsabile 10 14 20 30 Eros Bologna Coordinamento Ufficio Stampa CONS Testi Elisa Gianessi Uffici stampa federali Fotografie Alan Gasperoni Claudio Stefanelli Archivio CONS Archivi federali Michael Felici IOC LIBRARY Direzione e redazione Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Sammarinese Via Rancaglia 30 47899 – Serravalle Repubblica di San Marino Con la collaborazione di Rossana Ferri Alan Gasperoni Sommario Bruno Gennari Traduzioni 2018 Elledue-Assistenza linguistica srl 2 6 8 10 Stampa Focus sui giovani Un 2018 di grandi In mezzo al guado Per Mariotti Arti Grafiche Della Balda e coinvolgimento delle traguardi. Fissate già le un’Olimpiade donne per continuare prossime sfide da “gigante” a vincere 13 14 20 24 I prossimi appuntamenti Tarragona 2018, Quattro moschettieri La vision del Nado una storica a Buenos Aires San Marino: “Praticare doppietta d’oro lo sport in modo pulito e salutare, libero 28 30 32 36 Un pieno di sport San Marino 2017 Amarcord L’angolo del collezionista a -

10 the Relations Between the EU and Andorra, San Marino and Monaco

10 The relations between the EU and Andorra, San Marino and Monaco marc maresceau 10.1 Introduction Writing on the relations between the EU and Andorra, San Marino and Monaco is not an easy exercise.1 Various aspects make these relationships very complex. An important one has to do with history, whether or not in combination with geography. It is simply impossible to examine the rela- tionships between the EU and, for example, Andorra, without explaining why Andorra is where it is and how it comes that this piece of land in the heart of the Pyrenees is neither France nor Spain and not part of the EU. But entering into the unique and often fascinating history of micro-States in a contribution like this is an almost impossible venture. Constraints of various natures impose all kinds of limitations and the reality is such that only a very fragmented picture of the relevant historical facts can be provided. Nevertheless, the very short historical background to each of the three micro-States should help to elucidate their specificity in their present rela- tions with the EU. One of the characteristics common to all of the European micro-States is the very special relationship with their immediate neighbour or neighbours; this very often also explains why their neighbours did not absorb them. But this common feature is at the same time the characteristic which makes The author had the opportunity to discuss with H.E. the Ambassador of Andorra, Mrs Carme Sala; H.E. the Ambassador of San Marino, Mr Gian Nicola Fillipi Balestra; and H.E.